ENUM in the Netherlands December 2002

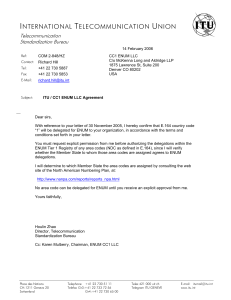

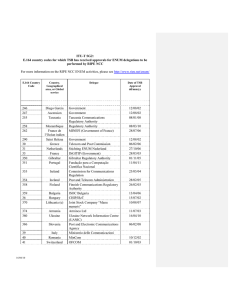

advertisement