Campbell Price, the Manchester Museum

advertisement

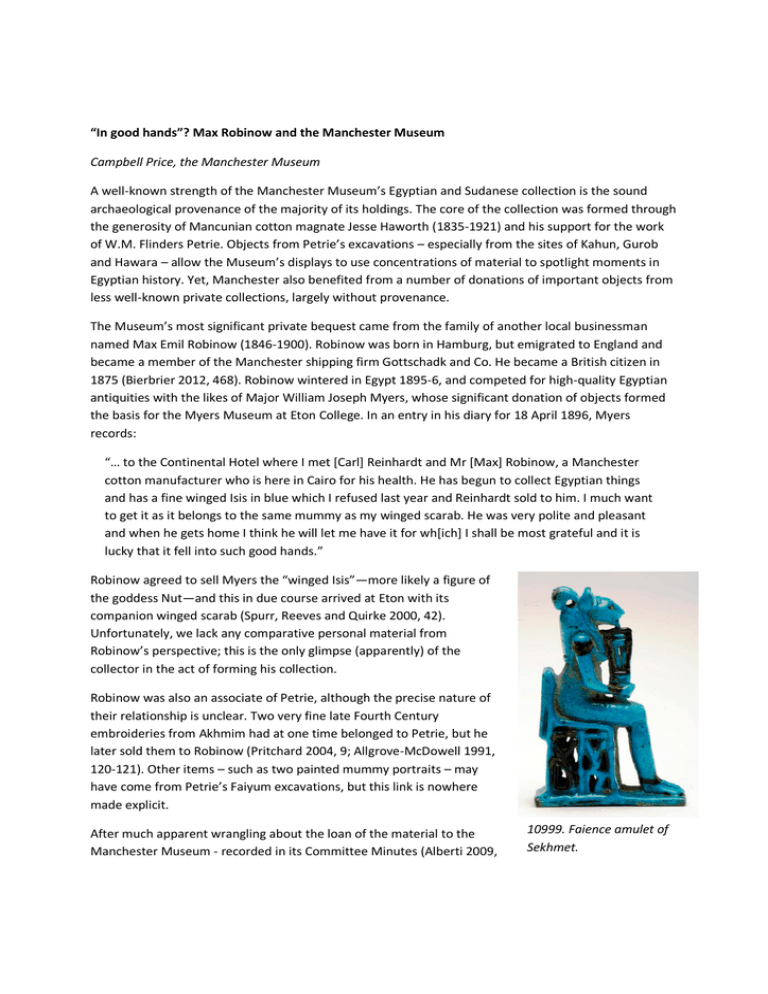

“In good hands”? Max Robinow and the Manchester Museum Campbell Price, the Manchester Museum A well-known strength of the Manchester Museum’s Egyptian and Sudanese collection is the sound archaeological provenance of the majority of its holdings. The core of the collection was formed through the generosity of Mancunian cotton magnate Jesse Haworth (1835-1921) and his support for the work of W.M. Flinders Petrie. Objects from Petrie’s excavations – especially from the sites of Kahun, Gurob and Hawara – allow the Museum’s displays to use concentrations of material to spotlight moments in Egyptian history. Yet, Manchester also benefited from a number of donations of important objects from less well-known private collections, largely without provenance. The Museum’s most significant private bequest came from the family of another local businessman named Max Emil Robinow (1846-1900). Robinow was born in Hamburg, but emigrated to England and became a member of the Manchester shipping firm Gottschadk and Co. He became a British citizen in 1875 (Bierbrier 2012, 468). Robinow wintered in Egypt 1895-6, and competed for high-quality Egyptian antiquities with the likes of Major William Joseph Myers, whose significant donation of objects formed the basis for the Myers Museum at Eton College. In an entry in his diary for 18 April 1896, Myers records: “… to the Continental Hotel where I met [Carl] Reinhardt and Mr [Max] Robinow, a Manchester cotton manufacturer who is here in Cairo for his health. He has begun to collect Egyptian things and has a fine winged Isis in blue which I refused last year and Reinhardt sold to him. I much want to get it as it belongs to the same mummy as my winged scarab. He was very polite and pleasant and when he gets home I think he will let me have it for wh[ich] I shall be most grateful and it is lucky that it fell into such good hands.” Robinow agreed to sell Myers the “winged Isis”—more likely a figure of the goddess Nut—and this in due course arrived at Eton with its companion winged scarab (Spurr, Reeves and Quirke 2000, 42). Unfortunately, we lack any comparative personal material from Robinow’s perspective; this is the only glimpse (apparently) of the collector in the act of forming his collection. Robinow was also an associate of Petrie, although the precise nature of their relationship is unclear. Two very fine late Fourth Century embroideries from Akhmim had at one time belonged to Petrie, but he later sold them to Robinow (Pritchard 2004, 9; Allgrove-McDowell 1991, 120-121). Other items – such as two painted mummy portraits – may have come from Petrie’s Faiyum excavations, but this link is nowhere made explicit. After much apparent wrangling about the loan of the material to the Manchester Museum - recorded in its Committee Minutes (Alberti 2009, 10999. Faience amulet of Sekhmet. 122, n. 110) – the Robinow Collection was finally transferred in January 1959, just after the death of Robinow’s son William in December 1958 (Museum Journal 1959, 110-111). A typed catalogue of the Robinow Egyptian collection made during the 1920s lists items numbered from 1-268 and 701-789, noting – intriguingly – that “the intervening numbers were not sent here.” If these pieces – which must originally have been counted and presumably numbered – are not in Manchester, then where are they? The Robinow material illustrates a range of problems encountered when tracing acquisitions which were not part of the known distribution system, and poses questions about the nature of collecting in the Nineteenth Century. Without a personal account like the one of Major Myers, for Robinow we have the objects, but almost nothing on the motive or the means – key narrative points that help to contextualise ‘a collection’, especially for a regional museum audience with interest in a local connection. So, for example, Jesse Haworth is synonymous with the Manchester collection and highlights the local philanthropic context for collecting. Indeed, some years ago his marble bust was moved from the Egyptian galleries he helped to finance to new a ‘Manchester Gallery’, which narrates why Manchester houses so many objects from such far-flung places in the first place. Another problem that arises from the Robinow collection is the individual quality of many of his pieces. By their nature, objects acquired by private collectors tend to be 11306. Painted mummy portrait of a more ‘glamorous’ than those found in secure soldier. An acquisition direct from Petrie? archaeological settings. Robinow – like Myers and countless others – was essentially ‘cherry-picking’ with the result that, on its own, his collection gives a skewed picture of ancient Egypt. Many of Robinow’s objects are display-worthy, and fill gaps in Manchester’s displays in areas Petrie’s finds cannot cover. How, then, can museums best explain that some the prettiest objects in a case are of less scientific value than their immediate neighbours, because of the total lack of provenance information? Robinow’s objects have a strong potential for future research, both individually and as a collection: a situation familiar to many museums around the world. Key questions include: Where are the ‘missing’ Robinow objects? How do Robinow’s pieces link to other objects in other collections? Should – and if so, how can – the unknown origin of the Robinow objects be explained to visitors when they are displayed next to more fragmentary, less attractive pieces from known archaeological contexts? And is the ‘messy’ story of the process of acquisition from Robinow’s family one that we want or need to tell? References Alberti, S. 2009. Nature and Culture. Objects, disciplines and the Manchester Museum. Manchester University Press: Manchester. Allgrove-McDowell, J. 1991. ‘Romano-Egyptian Embroidery: Autumn and Winter’, Hali 57, 120-121. Bierbrier, M. 2012. Who Was Who in Egyptology. 4th Revised Edition. EES: London. Pritchard, F. 2004. Clothing Culture: Dress in Egypt in the First Millennium AD. Whitworth Art Gallery: Manchester. Spurr, S, N. Reeves, and S. Quirke. Egyptian Art at Eton College. Selections from the Myers Museum. Yale University Press.