Document 12816675

Durant l'automne de 1775, Voltaire, alors octogénaire et saturé de gloire, était l'hôte de Frédéric au château de Sans-Souci.

Un jour les deux amis cheminaient aux environs de la résidence royale, et Frédéric se laissait charmer par les entraînants discours de son illustre compagnon, qui, fort en verve, exposait avec esprit et feu ses intransigeantes doctrines antireligieuses.

Oubliant l'heure en causant, les deux promeneurs, quand vint le coucher du soleil, se trouvèrent en pleine campagne.

À ce moment Voltaire était lancé dans une période particulièrement virulente contre les vieux dogmes qu'il combattait depuis si longtemps.

Tout à coup il se tut au milieu d'une phrase et resta sur place, gagné par un trouble profond.

Non loin de lui, une jeune fille à peine adolescente venait de s'agenouiller au tintement d'une cloche reculée, qui, du sommet d'une petite chapelle catholique, sonnait l'angélus. Récitant haut avec ferveur une prière latine, les mains jointes et la face tournée vers les cieux, elle ignorait la présence des deux étrangers, tant son extase l'emportait rapidement vers des régions de rêve et de lumière.

Voltaire la regardait avec une angoisse indicible, qui répandit sur sa face jaune et parcheminée une teinte plus terreuse encore que de coutume. Une émotion terrible crispa ses traits, tandis qu'influencé par l'idiome sacré de la prière entendue il laissait échapper inconsciemment, ainsi qu'un répons, ce mot latin:

«Dubito».

Son doute s'appliquait manifestement à ses propres théories sur l'athéisme. On eût dit qu'une révélation de l'au-delà s'opérait en lui à la vue de l'expression extra-humaine prise par la jeune fille en prière et qu'aux approches de la mort, forcément imminente à son âge, une terreur des châtiments éternels s'emparait de tout son être.

Cette crise ne dura qu'un instant. L'ironie crispa de nouveau les lèvres du grand sceptique, et la phrase commencée s'acheva sur un ton mordant.

Mais la secousse avait eu lieu, et Frédéric n'oublia jamais sa courte et précieuse vision d'un Voltaire

éprouvant une émotion mystique.

Raymond Roussel, Locus Solus (1914)

Francesco Orlando (1934-2010), Illuminismo e retorica freudiana, 1982

Francesco Orlando (1934-2010), Illuminismo e retorica freudiana, 1982

Sigmund Freud, Das Unheimliche (The Uncanny),

1919

Francesco Orlando (1934-2010), Illuminismo e retorica freudiana, 1982

Sigmund Freud, Das Unheimliche (The Uncanny),

1919

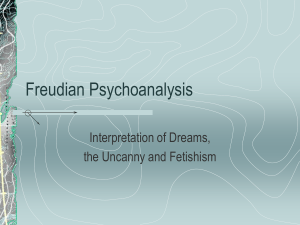

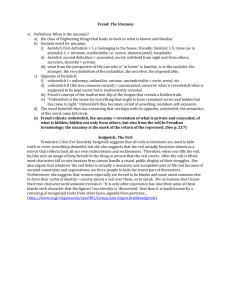

• The ‘Uncanny’ is not the horrid, nor the sublime

Francesco Orlando (1934-2010), Illuminismo e retorica freudiana, 1982

Sigmund Freud, Das Unheimliche (The Uncanny),

1919

• The ‘Uncanny’ is not the horrid, nor the sublime

• It is the feeling resulting from the ambiguous superimposition of familiarity and estrangement

Francesco Orlando (1934-2010), Illuminismo e retorica freudiana, 1982

Sigmund Freud, Das Unheimliche (The Uncanny),

1919

• The ‘Uncanny’ is not the horrid, nor the sublime

• It is the feeling resulting from the ambiguous superimposition of familiarity and estrangement

• Freud narrativizes the Uncanny as the ‘return of the repressed’

Francesco Orlando (1934-2010), Illuminismo e retorica freudiana, 1982

Sigmund Freud, Das Unheimliche (The Uncanny),

1919

• The ‘Uncanny’ is not the horrid, nor the sublime

• It is the feeling resulting from the ambiguous superimposition of familiarity and estrangement

• Freud narrativizes the Uncanny as the ‘return of the repressed’

• This repressed can be intended as referred to the individual psyche (phylogenesis) or to the cultural sphere, regarding the whole of humankind

(ontogenesis)

Francesco Orlando (1934-2010), Illuminismo e retorica freudiana, 1982

Sigmund Freud, Das Unheimliche (The Uncanny),

1919

• The ‘Uncanny’ is not the horrid, nor the sublime

• It is the feeling resulting from the ambiguous superimposition of familiarity and estrangement

• Freud narrativizes the Uncanny as the ‘return of the repressed’

• This repressed can be intended as referred to the individual psyche (phylogenesis) or to the cultural sphere, regarding the whole of humankind

(ontogenesis)

• In this last sense, the process of repression corresponds to the process of the Enlightenment

Francesco Orlando (1934-2010), Illuminismo e retorica freudiana, 1982

Sigmund Freud, Das Unheimliche (The Uncanny),

1919

‘We – or our primitive forefathers – once believed that these possibilities were realities [...]. Nowadays we no longer believe in them, we have surmounted

[überwunden] these modes of thought; but we do not feel quite sure of our new beliefs, and the old ones still exist within us [die alten leben noch in uns

fort] [...]. As soon as something actually happens in our lives which seems to confirm the old, discarded

[abgelegten] beliefs we get a feeling of the uncanny’.

Terry Castle, The Female Thermometer. 18th-century Culture and the Invention of

the Uncanny , 1995

The Uncanny is a ‘toxic sideeffect’ of the Enlightenment

• 1732: report Visum et Repertum

• 1746: Calmet, Dissertations sur les Apparitions […] et sur les

Revenans et Vampires

• 1748: Montesquieu, L’Esprit des lois

• 1751: first volume of Encyclopédie

• 1762: Rousseau, Du contrat social

• 1764: Walpole, The Castle of Otranto; Voltaire, Dictionnaire philosophique

• 1773: Bürger, Lenore; A. & J. Aikin, On the Pleasure Derived From

Objects of Terror

• 1776: United States Declaration of Independence

• 1784: Kant, Was ist Aufklärung?

• 1787: Schiller, Der Geisterseher

• 1789: French Revolution; first phantasmagoria shows in Paris

• 1794: Radcliffe, The Mysteries of Udolpho

• 1796: Lewis, The Monk

• 1797: Goethe, Die Braut von Korinth

Phantasmagoria

•

mid-seventeenth century: Athanasius Kircher and the magic lantern

•

1760s-1770s: Leipzig, "Schröpferesque Geisterscheinings” by

Johann Georg Schröpfer

•

1784: Henri Decremps, La magie blanche dévoilée

•

1787: Schiller, Der Geisterseher

•

1793: Paris shows by Philidor

•

1799: First show by Robertson

•

1812: publication of Fantasmagoriana

Robertson, Mémoires (1831)

Often, for blowing a last stroke, I ended my séances by giving this speech:

‘I have gone through all the phenomena of phantasmagoria; I unveiled for you the secrets of Memphis priests and of the Illuminati; I tried to show you the most occult aspects of physics, those effects that seemed to be supernatural in the centuries of credulity: but I still have to present one, to you, which is simply the most real. You, who may have smiled at my experiments, you, beauties who have experienced some moments of terror, behold the truly terrible show, the only one you have really to fear: be you strong, weak, or powerful men, be you believers or atheists, be you beautiful or ugly women, behold the destiny awaiting for you, behold what you will be one day: remember the phantasmagoria’.

At this point the light reappeared, and in the middle of the room one saw the skeleton of a young woman up on a pedestal.

One could perchance think that I should speak differently, and try to fortify the soul against the moral anxiety caused to us by the very thought of the supreme instant: but nature would speak louder than me.

I went towards the closet. But just imagine my mortal fear when, as I was about to open it, the two doors opened wide without a single sound; the lantern I was holding in my hand switched off, and, as if I was standing in front of a mirror, my faithful image came out of the closet; the shining she emanated enlightened a great part of the room. And then I heard these words: ‘Why are you trembling in beholding your very being, who is approaching you in order to bring you the knowledge of your coming death, and to reveal you the fate of your lineage?’

Fantasmagoriana, preface

It is generally believed that at this time of day no one puts any faith in ghosts and apparitions. Yet, on reflection, this opinion does not appear to me quite correct: for, without alluding to workmen in mines, and the inhabitants of mountainous countries, — the former of whom believe in spectres and hobgoblins presiding over concealed treasures, and the latter in apparitions and phantoms announcing either agreeable or unfortunate tidings, — may we not ask why amongst ourselves there are certain individuals who have a dread of passing through a church-yard after night-fall ? Why others experience an involuntary shuddering at entering a church, or any other large uninhabited edifice, in the dark ? And, in fine, why persons who are deservedly considered as possessing courage and good sense, dare not visit at night even places where they are certain of meeting with nothing they need dread from living beings ? They are ever repeating, that the living are only to be dreaded ; and yet fear night, because they believe, by tradition, that it is the time which phantoms choose for appearing to the inhabitants of the earth.

Admitting, therefore, as an undoubted fact, that, with few exceptions, ghosts are no longer believed in, and that the species of fear we have just mentioned arises from a natural horror of darkness incident to man, — a horror which he cannot account for rationally, — yet it is well known that he listens with much pleasure to stories of ghosts, spectres, and phantoms. The wonderful ever excites a degree of interest, and gains an attentive ear ; consequently, all recitals relative to supernatural appearances please us.

It was probably from this cause that the study of the sciences which was in former times intermixed with the marvellous, is now reduced to the simple observation of facts. This wise revolution will undoubtedly assist the progress of truth ; but it has displeased many men of genius, who maintain that by so doing, the sciences are robbed of their greatest attractions, and that the new mode will tend to weary the mind and disenchant study; and they neglect no means in their power to give back to the supernatural, that empire of which it has been recently deprived : They loudly applaud their efforts, though they cannot pride themselves on their success: for in physic and natural history prodigies are entirely exploded.

But if in these classes of writing, the marvellous and supernatural would be improper, at least they cannot be considered as misplaced in the work we are now about to publish : and they cannot have any dangerous tendency on the mind ; for the title-page announces extraordinary relations, to which more or less faith may be attached, according to the credulity of the person who reads them.

Besides which, it is proper that some repertory should exist, in which we may discover the traces of those superstitions to which mankind have so long been subject. We now laugh at, and turn them into ridicule : and yet it is not clear to me, that recitals respecting phantoms have ceased to amuse; or that, so long as human nature exists, there will be wanting those who will attach faith to histories of ghosts and spectres.