Skills, Networks & Knowledge: Developing a Career

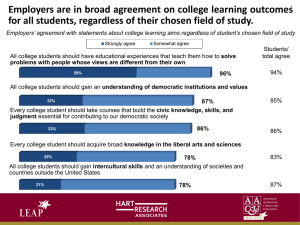

advertisement