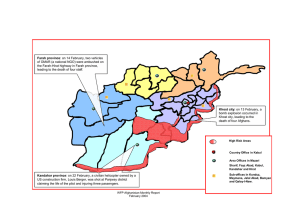

ZEF Working Paper Series 79

advertisement