Norges Bank Watch 2008 1

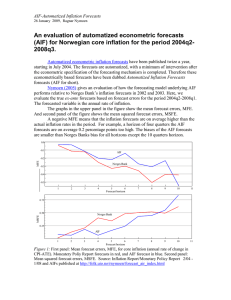

advertisement