IMPROVING CUSTOMER SATISFACTION THROUGH by KAREN L. KATZ

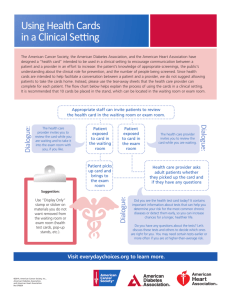

advertisement