On Making Sense JUN : 2010

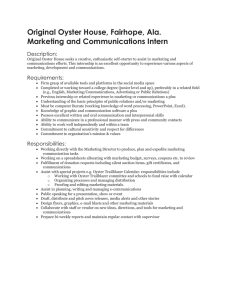

advertisement