Date: June 25, 2014 Department: Academic Literacy

advertisement

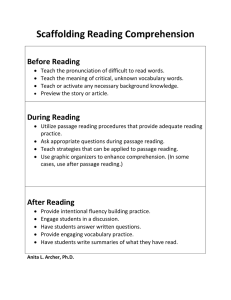

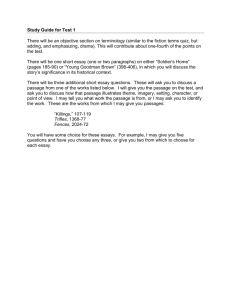

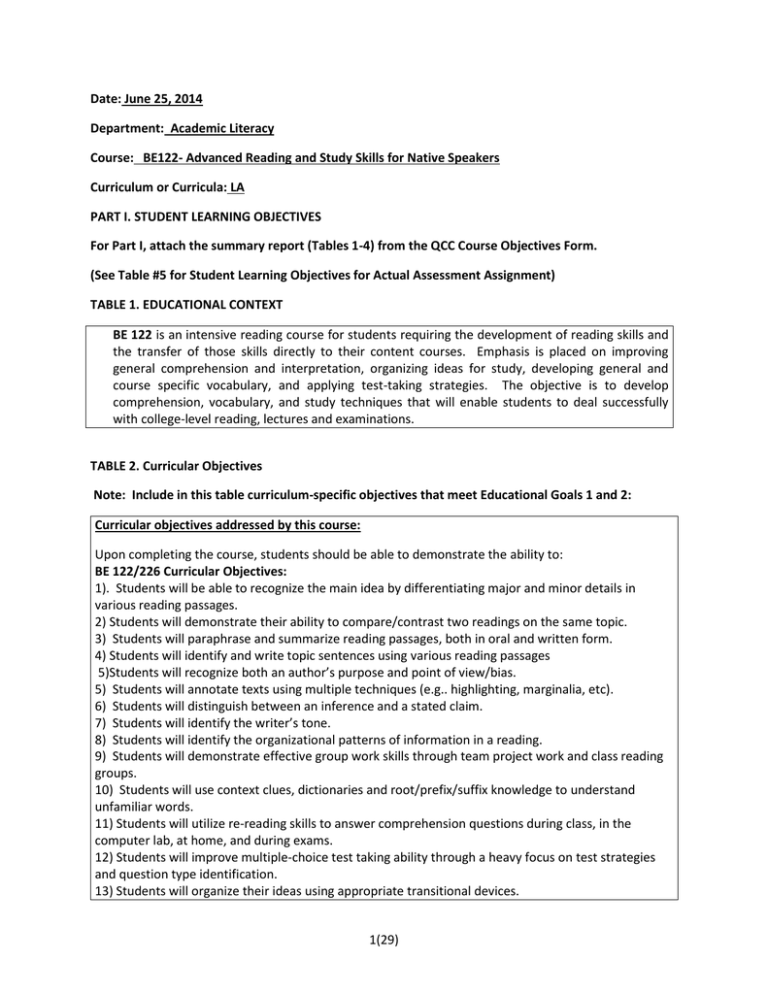

Date: June 25, 2014 Department: Academic Literacy Course: BE122- Advanced Reading and Study Skills for Native Speakers Curriculum or Curricula: LA PART I. STUDENT LEARNING OBJECTIVES For Part I, attach the summary report (Tables 1-4) from the QCC Course Objectives Form. (See Table #5 for Student Learning Objectives for Actual Assessment Assignment) TABLE 1. EDUCATIONAL CONTEXT BE 122 is an intensive reading course for students requiring the development of reading skills and the transfer of those skills directly to their content courses. Emphasis is placed on improving general comprehension and interpretation, organizing ideas for study, developing general and course specific vocabulary, and applying test-taking strategies. The objective is to develop comprehension, vocabulary, and study techniques that will enable students to deal successfully with college-level reading, lectures and examinations. TABLE 2. Curricular Objectives Note: Include in this table curriculum-specific objectives that meet Educational Goals 1 and 2: Curricular objectives addressed by this course: Upon completing the course, students should be able to demonstrate the ability to: BE 122/226 Curricular Objectives: 1). Students will be able to recognize the main idea by differentiating major and minor details in various reading passages. 2) Students will demonstrate their ability to compare/contrast two readings on the same topic. 3) Students will paraphrase and summarize reading passages, both in oral and written form. 4) Students will identify and write topic sentences using various reading passages 5)Students will recognize both an author’s purpose and point of view/bias. 5) Students will annotate texts using multiple techniques (e.g.. highlighting, marginalia, etc). 6) Students will distinguish between an inference and a stated claim. 7) Students will identify the writer’s tone. 8) Students will identify the organizational patterns of information in a reading. 9) Students will demonstrate effective group work skills through team project work and class reading groups. 10) Students will use context clues, dictionaries and root/prefix/suffix knowledge to understand unfamiliar words. 11) Students will utilize re-reading skills to answer comprehension questions during class, in the computer lab, at home, and during exams. 12) Students will improve multiple-choice test taking ability through a heavy focus on test strategies and question type identification. 13) Students will organize their ideas using appropriate transitional devices. 1(29) TABLE 3. General Education Objectives, based on draft Distributed at the January 2010 Praxis Workshops To achieve these goals, students graduating with an Associate degree will: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. Communicate effectively through reading, writing, listening and speaking. Use analytical reasoning to identify issues or problems and evaluate evidence in order to make informed decisions. Reason quantitatively and mathematically as required in their field of interest and in everyday life. Use information management and technology skills effectively for academic research and lifelong learning. Integrate knowledge and skills in their program of study. Differentiate and make informed decisions about issues based on multiple value systems. Work collaboratively in diverse groups directed at accomplishing learning objectives. Use historical or social sciences perspectives to examine formation of ideas, human behavior, social institutions, or social processes. Employ concepts and methods of the natural and physical sciences to make informed judgments. Apply aesthetic and intellectual criteria in the evaluation or creation of works in the humanities or the arts. Gen Ed objective’s ID number from list (1-10) General educational objectives addressed by this course: Select from preceding list. 1. Communicate effectively through reading, writing, listening and speaking. 2. Use analytical reasoning to identify issues or problems and evaluate evidence in order to make informed decisions. Work collaboratively in diverse groups directed at accomplishing learning objectives. 7. TABLE 4: Course Objectives and student learning outcomes Course Objectives and Desired Outcomes 2(29) 1) Students will be able to recognize the main idea by differentiating major and minor details in various reading passages. 2) Students will demonstrate their ability to compare/contrast two readings on the same topic. 3) Students will paraphrase and summarize reading passages, both in oral and written form. 4) Students will identify and write topic sentences using various reading passages 5)Students will recognize both an author’s purpose and point of view/bias. 5) Students will annotate texts using multiple techniques (e.g.. highlighting, marginalia, etc). 6) Students will distinguish between an inference and a stated claim. 7) Students will identify the writer’s tone. 8) Students will identify the organizational patterns of information in a reading. 9) Students will demonstrate effective group work skills through team project work and class reading groups. 10) Students will use context clues, dictionaries and root/prefix/suffix knowledge to understand unfamiliar words. 11) Students will utilize re-reading skills to answer comprehension questions during class, in the computer lab, at home, and during exams. 12) Students will improve multiple-choice test taking ability through a heavy focus on test strategies and question type identification. 13) Students will organize their ideas using appropriate transitional devices. PART ii. Assignment Design: Aligning outcomes, activities, and assessment tools For the assessment project, you will be designing one course assignment, which will address at least one general educational objective, one curricular objective (if applicable), and one or more of the course objectives. Please identify these in the following table: TABLE 5: OBJECTIVES ADDRESSED IN ASSESSMENT ASSIGNMENT Course Objective(s) selected for assessment: (select from Table 4) 3. Paraphrase and summarize reading passages, both in oral and written form. Curricular Objective(s) selected for assessment: (select from Table 2) 1. Students will be able to recognize the main idea by differentiating major and minor details in various reading passages. 3. Students will paraphrase and summarize reading passages, both in oral and written form. 4. Students will identify and write topic sentences using various reading passages 13. Students will organize their ideas using appropriate transitional devices. 9. Students will demonstrate effective group work skills through team project work and class reading groups. 3(29) General Education Objective(s) addressed in this assessment: (select from Table 3) 1. Communicate effectively through reading, writing, listening and speaking. Reading: Students will read various passages and summarize them. Writing: Students will write summaries. Listening and speaking: Students will discuss key components of main ideas in passages and summary writing in pairs, groups and as a class. 2. Students will use analytical reasoning to identify issues or problems and evaluate evidence in order to make informed decisions. Students will make informed decisions about which ideas are most important to include in their summaries. 7. Students will work collaboratively in diverse groups directed at accomplishing learning objectives. Student Learning Outcomes: 1. Students will differentiate between major and minor details in reading passages. 2. Students will organize their ideas using appropriate transitional devices. 3. Students will write effective summaries on various reading passages. In the first row of Table 6 that follows, describe the assignment that has been selected/designed for this project. In writing the description, keep in mind the course objective(s), curricular objective(s) and the general education objective(s) identified above, The assignment should be conceived as an instructional unit to be completed in one class session (such as a lab) or over several class sessions. Since any one assignment is actually a complex activity, it is likely to require that students demonstrate several types of knowledge and/or thinking processes. Also in Table 6, please a) identify the three to four most important student learning outcomes (1-4) you expect from this assignment b) describe the types of activities (a – d) students will be involved with for the assignment, and c) list the type(s) of assessment tool(s) (A-D) you plan to use to evaluate each of the student outcomes. (Classroom assessment tools may include paper and pencil tests, performance assessments, oral questions, portfolios, and other options.) Note: Copies of the actual assignments (written as they will be presented to the students) should be gathered in an Assessment Portfolio for this course. 4(29) TABLE 6: Assignment, Outcomes, Activities, and Assessment Tools Briefly describe the assignment that will be assessed: Students will be taught to read a short passage and summarize it effectively. Desired student learning outcomes for the assignment (Students will…) Briefly describe the range of activities student will engage in for this assignment. What assessment tools will be used to measure how well students have met each learning outcome? (Note: a single assessment tool may be used to measure multiple learning outcomes; some learning outcomes may be measured using multiple assessment tools.) Baseline Assessment 1. Instrument Used: A Summary Scoring Rubric derived from the (MTEL) Communication and Literacy Skills Test (01) – List in parentheses the Curricular Objective(s) and/or General Education Objective(s) (1-10) associated with these desired learning outcomes for the assignment. Students will be able to recognize the main idea by differentiating major and minor details in various reading passages.(Curricular Objective #1) Students will identify and write topic sentences using various reading passages.(Curricular Objective #4) Students will summarize reading passages by identifying main ideas, organizing these ideas effectively, using appropriate transitional devices, and producing their summaries by using their own words.(Curricular Objective #3) Students will communicate effectively through reading, writing, listening and speaking. (General Education Objective#1) Students will use analytical reasoning to identify issues or problems and evaluate evidence in order to make informed decisions. (General Education Objective #2) In early February 2014, to form baseline data the instructors were asked to assess their students’ summarizing skills. Students were given a reading entitled, “Why Losing is Good for You” (See Attachment.) to read and summarize. The MTEL Rubric was used to evaluate their performance. (See Attachment.) Preparation for Mid-term Assessment: In late February, instructors were given a specific lesson on summary writing to assist their students in learning this skill. Day of the Lesson: After teachers taught their students how to write a summary, which took approximately forty minutes, they gave students the passage on “Why Obesity Among 5 Year Olds Is So Dangerous” “to read. (See Attachment.) 5(29) The baseline, mid-term, and final summary results were examined using the MTEL rubric. (See Attachment.) Improvements between assessments were evaluated across sections and assessments to determine the improvement in students’ ability to write cohesive, accurate, and well-written summaries. Students will work collaboratively in diverse groups directed at accomplishing learning objectives. (General Education Objective #7) This task took approximately twenty-minutes. Once the students had finished reading it, they worked in pairs to write a summary of it. This task took approximately twenty to twenty-five minutes. Once the students finished writing their summaries, the teachers noted the keys ideas of the passage on the board and asked students to verify whether or not they included these ideas. If they hadn’t, they were instructed to jot down notes below their summaries and, revise their summaries at home. Finally, the teacher gave students the second article, entitled, “Premature Babies: Talking to Them Improves their Language Development” and asked them to summarize it for homework. During the following class the teachers asked learners to submit homework summaries and revised in-class summaries. At the beginning of class, teachers discussed the key points of the homework reading/summary. This took approximately fifteen minutes to twenty minutes. Mid-term Assessment: Several classes later, the students participated in the Department’s Mid-term Assessment of summary skill writing, which was measured with the MTEL. It should be noted that it is a departmental practice for all reading students to participate in this midterm 6(29) summary assessment. This task required an entire class period. The mid-term reading “The Road to Ivory is Stained with Blood”. Once the students finished writing their summaries, teachers placed them in the Dr. Julia Carroll’s (Chairperson of the Department’s Assessment Committee) mailbox labeled with the teacher’s name and class sections on them. The Assessment Committee then evaluated the summaries according to the MTEL rubric and recorded the scores on a separate file. Finally, the summaries were returned to the teachers. Preparation for the Final Assessment: At the end of the semester, the students participated in the Department Final Summary Assessment. Like the Mid-term, this assessment was a Department-wide Assessment, which all reading students were obligated to take. Prior to this assessment, teachers repeated the summary lesson with their own readings passages. By revisiting this lesson, the teachers employed a spiral pedagogical approach whereby the same or very similar lesson was repeated on several occasions to reinforce learning. Day of the Actual Final Assessment 7(29) The teachers administered the Final Exam, which included a summary. The passage that the students read and summarized was entitled “Paying a Price for Loving Red Meat”. The students were given the entire class period to complete the exam. Once again, teachers placed the materials in Dr. Carroll’s mailbox and the Assessment Committee evaluated them and recorded the scores on a separate roster, which was held on file. Part iii. Assessment Standards (Rubrics) Before the assignment is given, prepare a description of the standards by which students’ performance will be measured. This could be a checklist, a descriptive holistic scale, or another form. The rubric (or a version of it) may be given to the students with the assignment so they will know what the instructor’s expectations are for this assignment. Please note that while individual student performance is being measured, the assessment project is collecting performance data ONLY for the student groups as a whole. Table 7: Assessment Standards (Rubrics) Describe the standards or rubrics for measuring student achievement of each outcome in the assignment: This assessment used the (MTEL) Communication and Literacy Skills Test (01) during the spring semester of 2014 to evaluate the summary skills of six sections of BE122 students on three separate occasions during the semester. The first summary was used as a baseline assessment to ascertain how well students performed before receiving instruction. The next assessment was performed at the midterm after the students had experienced a specific summary lesson and practice activities. Finally, the last summary assessment was utilized at the end of the semester to measure the improvement across all three assessments. Instrument Used: A Summary Scoring Rubric derived from the (MTEL) Communication and Literacy Skills Test (01) – Background: The MTEL Summary Scoring Rubric was developed by Department of Education of Massachusetts and Pearson Education. It is a combined reading and writing test that incorporates the comprehension and analysis of readings as well as outlining and summarizing. It was first copyrighted in 2008 through Pearson Education. 8(29) The Department of Academic Literacy at QCC utilizes this rubric to assess summary writing at midterms and finals across all reading courses. In addition, many writing instructors use it as well as a tool to assist their students with summary writing as part of their CATW assessment preparation. Since this rubric has been successfully used as the official rubric to assess summary writing throughout the Department, the members of the Assessment Committee concluded that it was an appropriate evaluation tool for the task of summary writing. This rubric consists of a four-point scale. The score of one represents the lowest score and is not passing. Two is approaching a passing level. Three is passing, and four is higher than passing. Some of the most important criteria that these scores are based on include: the extent to which the student understood the main idea of the article, how well the student organized his or her own ideas, the degree to which the student used his or her own words, and how clearly the summary was written. This rubric was provided to the BE122 instructors before they taught their lessons. Before their students participated in the assessments, the instructors discussed the criteria of the rubric so that the students would clearly understand how they were to be evaluated. How the MTEL Rubric Measured Curricular and General Educational Objectives for this Assessment: This rubric measured both Curricular Outcomes and General Education Outcomes. Curricular Objectives: 1. Students will be able to recognize the main idea by differentiating major and minor details in various reading passages.(Curricular Objective #1)- This curricular objective is included the in the MTEL because it examines how well students are able to locate an article’s most important ideas. 2. Students will identify and write topic sentences within various reading passages.(Curricular Objective #4). In order for the students to develop the ability to convey the main ideas of an article, the students were required to write clear and focused topic sentences. 3. Students will summarize reading passages by identifying main ideas, organizing these ideas effectively, using appropriate transitional devices, and producing their summary by using their own words.(Curricular Objective #3). All of these components above are included in the MTEL rubric. General Educational Objectives: 1. Communicate effectively through reading, writing, listening and speaking. (General Education Objective#1). The rubric measured how well the students read and understood reading passages as well as their ability to write an effective summary. Part iv. assessment results TABLE 8: Summary of Assessment Results Use the following table to report the student results on the assessment. If you prefer, you may report outcomes using the rubric(s), or other graphical representation. Include a comparison of the outcomes you expected (from Table 7, Column 3) with the actual results. NOTE: A number of the pilot assessments did not include expected success rates so there is no comparison of expected and actual outcomes in some of the examples below. However, projecting outcomes is an important part of the 9(29) assessment process; comparison between expected and actual outcomes helps set benchmarks for student performance. TABLE 8: Summary of Assessment Results (Part of TABLE 9’s focus is subsumed in this section.) The committee started with the assumption that scores would increase as a result of (a) the lesson, and (b) multiple exposures to the new skill in a variety of situations (solo, group, and class-wide experiences). However, no specific expectations about the degree of improvement were hypothesized. Thus, the generally positive results seem to indicate a highly successful unit. Student achievement: Describe the group achievement of each desired outcome and the knowledge and cognitive processes demonstrated: The lesson had one desired outcome: to improve students’ ability to write effective summaries. The following analysis indicates a improvement from the baseline assessment to the final assessment and from the midterm and to the final (See Table 1). Table 1: Assessment Results for- MTEL Summary Scoring Rubric Summary n Baseline Average Score Mid-term Summary n Mid-Term Summary Average Score Final Summary n Final Summary Average A 21 2.4 21 2.1 20 2.7 B 18 1.8 15 2.1 12 2.8 C 15 2.3 15 2.5 17 2.7 D 20 2.1 18 2.4 15 2.9 E 23 2.3 18 2.2 21 2.5 F 20 1.9 19 2.2 20 2.8 Total 117 2.13 (average score) 106 2.25 105 2.73 BE122 Baseline Discussion of Results Related to Average Score on Assessment: On the MTEL scoring rubric (Table 1), the passing score is “3” for summary writing. Data indicates that the average score was above “2” in four of the six sections on the baseline summaries before instruction. The average score was above “2” for all six sections on the mid-term after the students had received a specific lesson on summary writing, and by the final assessment the average score was significantly above “2” for all six sections. Sections B, D, and F average scores were within two points from an overall passing score on the final assessment 10(29) The average score on the final assessment for all six sections was 2.73, which is a +29.3% increase in overall improvement. Even though a 2.73 is not quite a “3” which is considered a “passing” score, a considerable number of students received at least a three or higher. In fact, in the baseline assessment, only 29 students scored a 3 or higher. On the midterm assessment, 36 students scored a 3 or higher; however, on the final assessment 72 students earned a score of 3 or higher (See Figure 1.). Table 2: Assessment Results for Percentage of Change between Assessments- Using the MTEL Rubric BE122 Percentage of change between the Baseline and the Mid-term Percentage of change between the Mid-term and the Final Percentage of change between the Baseline and the Final A -12.50% 28.57% 12.50% B 16.67% 33.33% 55.56% C 8.70% 8.00% 17.39% D 14.29% 20.83% 38.10% E -4.35% 13.64% 8.70% F 15.79% 27.27% 47.37% Total 6.43% 21.94% 29.93% Discussion of Results Related to Percentage of Change: Percentage of Change between the Baseline and the Mid-term: In four sections of the six, B, C, D, and F, respectively, that were assessed, a positive change resulted between the baseline and the mid-term, with section B scoring the highest +16.67%. The two sections with the weakest performance were section A, which had a -12.5% percentage change and section E, which had a -4.35% change. This may have been because the Department mid-term assessment occurred directly after spring break, and some students may have had some difficulty transitioning. However, overall students in four sections out of the six showed general improvement. Percentage of Change between the Mid-term and the Final: Between the mid-term and the final assessments, the results evidenced a positive change in all six sections, with section B presenting the highest rate of improvement at 33.33%. Sections A and F also demonstrated notable improvement, with scores of +28.57% and +27.27% respectively. Students in Section A made considerable progress moving from an average score of a 2.1 to a 2.7. Students in section F moved from 2.2 to 2.8. Each of these sections had an average final assessment score of 2.73, which is close to the passing score of a “3”. Although the average is below “3”, many students overall did achieve the score of a three as will be illustrated in Figure #1. 11(29) Percentage of Change between the Baseline and the Final: Between the beginning and the end of the semester, all six sections of BE122 demonstrated improvements in their ability to write a well-organized, cohesive, academic summary. The analysis and comparison of the original scores on the baseline assessment to the final assessment indicate improvement over time. All six sections demonstrated a positive change between assessments with sections B and F scoring the highest at +55.56% and +47.37%. Students Scoring “3” or Higher on Assessment: The previous two data tables reveal that over time students in all six sections of BE122 improved their ability to write a well-written academic summary. However, it still must be noted that even by the end of the semester, the average score on the final assessment, 2.73, was under a “3” which is considered to be the lowest passing score using the MTEL Summary Scoring Rubric. Nevertheless, as can be noted from the bar graph below, as the semester progressed an increased number of students were able to pass the assessment. Figure 1 Percentage of Students Scoring at least a 3 on Assessments Students Scoring 3 or Higher 80 70 60 Score on Baseline Assessment 50 40 Score on Mid-term Assessment 30 20 Score on Final Assessment 10 0 Score on Baseline Assessment Score on Mid- Score on Final term Assessment Assessment Baseline Assessment Mid-term Assessment Final Assessment Out of 117 students, 29 students scored a “ 3” or higher or 25% Out of 106 students, 36 students scored “3” or higher or 34% Out of 105 students 72 were able to score “3” or higher on the final assessment or 69% 12(29) Table 3: Comparison of Means for the MTEL Summary Scoring Rubric n Mean SD Baseline Score 114 2.13* .65956 Midterm Score 104 2.25* .63090 Final Score 105 2.73* .52314 p < .0001 In Table 3, a t-test of dependent means also revealed a statistically significant increase in scores between a) the baseline assessment and the midterm, b) the midterm assessment and the final, and c) the Baseline assessment and the final (p < .0001). These analyses suggest that teaching the students’ summary writing skills at the beginning of the term improved their ability to compose summaries significantly; however, repeating the lesson and offering additional opportunities to write more summaries improved their performance even more. Thus, these results suggest that when teachers engage in a spiral approach to teaching new skills to their developmental reading students, their learners reap the benefit of repeated lessons and practice because this repetition advances their summary writing scores. As Table 4 indicates an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and a Tukey HSD revealed a statistically significant difference (p < .05) between groups 1 and 2 during the baseline assessment. However, after the midterm and final assessments, no statistical differences were evidenced among any of the classes. These results suggest that student population was similar, and the summary lesson and instruction in all six classes was consistent and similar since no significant differences were demonstrated. Table 4 Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) among Six Classes Baseline Score Df 5 f 2.403 Significance .042* Midterm Score 5 .925 .468 Final Score 5 .828 .533* p < .05 13(29) Correlational Analyses of the Data To examine the relationships among the summary tasks and the ACT Reading scores, the following correlations were conducted. Table 5 Correlation of Summary Scores to ACT Reading Scores Summary Base Line Base Line Midterm Final ACT Reading Score .246* .070 .180 .321** .266* Midterm .246* Final .070 .321** ACT Reading Score .180 .266* .373** .373** p < .05 ** p < .01 Correlational analyses revealed: 1. a weak positive correlation (.246) between the baseline summary scores and the midterm summary scores (p < .05); 2. a moderate positive correlation (.321) between midterm summary scores and the final summary scores (p < .01); 3. a weak positive relationship between the midterm summary scores and the ACT Reading scores; and 4. a moderate positive correlation between the final summary scores and the ACT Reading scores. A weak positive correlation between the baseline summary scores and the midterm summary scores (.246) suggests that although the students had received specific instruction and practice in summarizing, their performance on the midterm still evidenced a weak relationship with their baseline scores. However, after the students received additional instruction and practice in summarizing, their final scores moderately correlated with their ACT Reading scores. Thus, these correlations suggest that as the students enhance their ability to summarize, they also advance their ACT Reading scores. This is 14(29) an important finding because the level at which a student can compose a summary is related to his/her ability to perform on the ACT Reading exam and thereby provides another assessment tool to the teachers when they are trying to understand why certain students fail the ACT Reading while others succeed. It also implies that remedial reading students require multiple learning experiences before they comprehend new topics. TABLE 9. Resulting Action Plan In the table below, or in a separate attachment, interpret and evaluate the assessment results, and describe the actions to be taken as a result of the assessment. In the evaluation of achievement, take into account student success in demonstrating the types of knowledge and the cognitive processes identified in the Course Objectives. A. Analysis and interpretation of assessment results: See section 8 above. B. Evaluation of the assessment process: What do the results suggest about how well the assignment and the assessment process worked both to help students learn and to show what they have learned? Judging by the increase in the students’ average scores across all three implementations of the assessment, it appears that both the assignment and the assessment process yielded significant outcomes. The students’ average score on the baseline assessment was 2.13. After the first lesson and the mid-term assessment, the scores increased to 2.25, and after the final spiral lesson and assessment it increased again to 2.73. From the original baseline to final assessment, this is an increase of 29.93%. In section E, there was a slight dip between the baseline, an average score of 2.3 to the mid-term to 2.2; however, by the final assessment, the students had increased their overall average to 2.5, which is still moderately higher than their baseline score of 2.3, which was achieved early in the semester. This variation could have resulted from the students’ self-selection when they registered for specific sections of BE122. In addition, a large number of students that participated in the study, 72 out of 106, had achieved passing scores of least a 3 by the final assessment. These results again demonstrate the effectiveness of both the assignment and the assessment process itself. C. Resulting action plan: Based on A and B, what changes, if any, do you anticipate making? Modest to gains were achieved using, the MTEL, to measure summary skills across the three implementations of the assessment instrument from the baseline to the mid-term to the final assessment. The results from this assessment revealed that the students’ ability to summarize improved over time with repeated lessons and practice. This assessment insinuates that explicit repeated teaching of a) differentiating the main idea of a 15(29) passage from extraneous minor details, b) paraphrasing , c) using transitions, and d) organizing a wellorganized cohesive summary, leads to enhanced ability to write effective summaries. Since summary writing is an essential skill on Department Summary Reading Test, the BE122 faculty will be encouraged to use this repeated-teaching and testing method as they fine tune their courses. Since most remedial students arrive with weak academic skills, they require as much exposure to academic language and repeated specific instructions as possible. This can consist of additional repeated lessons, challenging academic material, and consistent review of the skills necessary to write an effective summary. As BE122 students are in the highest level of our reading program, it is also recommended that instructors require their students to read two novels instead of one. These books should be at a challenging level to ensure that they are academically prepared for the credit-bearing courses that they will need to complete once they leave our department because credit-bearing courses often consist of a rigorous curriculum that includes extensive reading. Therefore, our students need to increase their reading speed, overall reading comprehension levels, as well as general language acquisition. This can be accomplished when they are expected to read and write prolifically at high reading levels. Instructors can then be encouraged to require their students to summarize various chapters of these novels to progress their overall summary writing skill, which will also be needed in their credit-bearing classes. To enhance this summary writing lesson further, instructors can be encouraged to develop model summaries that directly correspond to the criteria of the rubric being utilized. For instance, students can be provided with model summaries that have received the score of a 1, 2, 3, or 4 on the rubric. The models can be distributed to the students without their corresponding scores and then the students can work in groups to assess each summary. The classroom instructor can then lead the students through a discussion/analysis of the scores that each summary should have received and the rationale behind each decision so that the students view summarizing from the teacher’s perspective. After this review, the students should score each other’s summaries to enhance their understanding of this skill by analyzing and discussing their summaries along with the rubric. Likewise, all BE122 instructors should participate in departmental norming sessions during which they utilize these model summaries along with their corresponding rubrics to ensure consistency and accuracy in their grading. These sessions will also permit teachers to glean ideas from one another to enhance their summary teaching and evaluation skills even more. This will be especially helpful in that it will increase the likelihood of fewer discrepancies among sections because the instructors will be exposed to increased support among peers and other professionals in their fields. 16(29) Addendum: These documents were included in the instructor’s packet for the Spring 2014 Assessment of BE 122. They include: a) the lesson plan, b) reading passages and c.) the rubric The reading passages and MTEL Summary Scoring Rubric referred to in the lesson are attached to the end of this section. Overview of the Lesson for Session #1 The focus of this lesson is finding the key ideas in a reading passage and writing a summary about those key ideas. The focus of the lesson will be the following: Review the MTEL Summary Scoring Rubric with particular focus on a score of “3” as a passing summary. Read the passage Identify the overall topic, main idea, and key ideas within the passage. Draft a summary. Include transition words that indicate an additional idea. Edit for simple sentence structure and main idea/key ideas (time permitting) The Summary Rubric The Department of Academic Literacy at QCC utilizes the MTEL Summary Scoring Rubric to assess summary writing at midterms and finals across all reading courses. This rubric consists of a four-point scale. The score of one represents the lowest score and is not passing. Two is approaching a passing level. Three is passing, and four is higher than passing. Some of the most important criteria that these scores are based on include: the extent to which the student understood the main idea of the article, how well the student organized his or her own ideas, 17(29) the degree to which the student used his or her own words, and how clearly the summary was written. To help students understand the important parts of a summary, you can focus on “3” on the four-point scale as the target for summary writing because it is considered to be a passing score. We suggest that you and the students use the attached rubric to carefully examine differences in scores on the scale; such analysis can help students to understand the differences between a failing and passing summary score. One approach is to focus on the description of how well main ideas and significant details are conveyed in the summary at the “3” level vs. the “2” or “1”. For example, going from “3” to “1” on the scale reveals different levels of performance in summary writing. You can ask the students to examine the first bullet point in score level and underline the words that show those differences and consider the meaning with regard to scoring: 3 The response conveys most of the main ideas and significant details of the original passage, and is generally accurate and clear. 2 The response conveys only some of the main ideas and significant details of the original passage. 1 The response fails to convey the main ideas and details of the original passage. 18(29) Once students analyze those differences in scoring, you could ask them to consider the “4” vs. “3” level by eliciting definitions for “accurately” and “clearly” in the context of good summary writing. 4 The response accurately and clearly conveys all of the main ideas and significant details of the original passage. If time permits further analysis, you and the students can compare other bullet points in scoring levels (paraphrasing, organization, and clarity). The Reading Passage #1 The attached reading passage (Why Obesity Among 5 Year Olds Is So Dangerous) will be used to demonstrate how to find the topic, main idea, and key ideas. We suggest that you and the students work together on the initial part of this task (finding the topic and main idea) and allow them to work in pairs for the second part of the task (finding key ideas). Determining the Topic and Main Idea of Reading Passage #1 1. The topic of a reading passage is usually a few words that express the most general point that is discussed in the passage. Elicit student responses about the topic of the passage. 2. Next, the main idea of the entire passage usually contains the topic and the author’s opinion or the point being made. Elicit student responses about the main idea of the passage. Determining the Key Ideas in the Passage After you and the students have reviewed the topic and main idea of the passage, you can ask pairs to find the key ideas in the passage. It is sometimes challenging for developmental 19(29) reading students to understand the difference between general and specific ideas. Therefore, we recommend that you work on this concept with the students before they participate in pair work. For example, you can write down several examples of general vs. specific ideas on the board to model this concept and/or elicit examples from the students such as fruit (general) and kinds of fruit (specific). When you think students are ready to work on their own, ask them to highlight or underline only the key ideas in this passage. When the pairs have finished, review key ideas with the whole class. Paraphrasing for the summary After the topic, main idea, and key ideas have been identified, pairs can work on drafting the summary. Drafting a passing summary (“3” score) requires paraphrasing, and we suggest you elicit students’ knowledge of this skill. Depending on student responses about paraphrasing, you may want to say that writing a good summary means that students should change some of verbs, adjectives, and nouns with synonyms (or words with similar meanings), and/or sentence structure. Below is one example of changing verbs, adjectives and/or nouns: Example #1: Original sentence: A new report that studied kids throughout childhood found that those who are obese at five years old are more likely to be heavy later in life. Revised sentence: A recent longitudinal study of children revealed that overweight five-yearolds were more likely to be overweight adults. Below is an example of changing sentence structure from compound to complex: 20(29) Example #2: Original sentence: The study highlights the dynamic between early weight gain and obesity, and the researchers say future work should focus on understanding what contributes to a child becoming overweight so early in life. Revised sentence: Since the research shows how gaining weight during childhood is linked to obesity, researchers believe that other studies should explore contributing factors that lead to early childhood obesity. Writing the Summary Ask students to draft a summary by stating the following: The title of the passage The author of the passage The topic of the passage The main idea The key ideas Adding Transition Words The next part of drafting a summary is writing with coherence. Again, coherence may be a complex or unknown term for developmental reading students, so we recommend discussing this aspect as making connections with words that add ideas. Elicit transition words that help students to add ideas into their writing. Ask students to look at their summary closely to see where they might be able to add transition words. The Homework Assignment 21(29) For homework, ask students to read the attached passage #2 (Premature Babies: Talking to Them Improves their Language Development) and draft a summary on their own. Remind them that the summary should include the title, author’s name, topic, main idea, and key ideas. Session #2 Review the homework summary as a whole class for content and coherence. After homework review, assign the individual in-class assessment activity. Baseline Reading Losing Is Good for You By ASHLEY MERRYMAN Trophies were once rare things — sterling silver loving cups bought from jewelry stores for truly special occasions. But in the 1960s, they began to be mass-produced, marketed in catalogs to teachers and coaches, and sold in sporting-goods stores. Today, participation trophies and prizes are almost a given, as children are constantly assured that they are winners. One Maryland summer program gives awards every day — and the “day” is one hour long. In Southern California, a regional branch of the American Youth Soccer Organization hands out roughly 3,500 awards each season — each player gets one, while around a third get two. Nationally, A.Y.S.O. local branches typically spend as much as 12 percent of their yearly budgets on trophies. It adds up: trophy and award sales are now an estimated $3 billion-a-year industry in the United States and Canada. By age 4 or 5, children aren’t fooled by all the trophies. They are surprisingly accurate in identifying who excels and who struggles. Those who are outperformed know it and give up, while those who do well feel cheated when they aren’t recognized for their accomplishments. They, too, may give up. It turns out that, once kids have some proficiency in a task, the excitement and uncertainty of real competition may become the activity’s very appeal. If children know they will automatically get an award, what is the impetus for improvement? Why bother learning problem-solving skills, when there are never obstacles to begin with? 22(29) If I were a baseball coach, I would announce at the first meeting that there would be only three awards: Best Overall, Most Improved and Best Sportsmanship. Then I’d hand the kids a list of things they’d have to do to earn one of those trophies. They would know from the get-go that excellence, improvement, character and persistence were valued. One researcher warns that when living rooms are filled with participation trophies, it’s part of a larger cultural message: to succeed, you just have to show up. In college, those who’ve grown up receiving endless awards do the requisite work, but don’t see the need to do it well. In the office, they still believe that attendance is all it takes to get a promotion. However, in life, you’re going to lose more often than you win, even if you’re good at something. You’ve got to get used to that to keep going. When children make mistakes, our job should not be to spin those losses into decorated victories. Instead, our job is to help kids overcome setbacks, to help them see that progress over time is more important than a particular win or loss, and to help them graciously congratulate the child who succeeded when they failed. To do that, we need to refuse all the meaningless plastic and tin destined for landfills. We have to stop letting the trophy industry run our children’s lives. READINGS USED AS PART OF LESSON Reading Passage #1- (In-Class Practice) Why Obesity Among 5 Year Olds Is So Dangerous By Alexandra Sifferlin A new report that studied kids throughout childhood found that those who are obese at five years old are more likely to be heavy later in life. While other studies have hinted at that trend, those have generally involved what’s known as prevalence of the condition — or the proportion of a population, at a given time, that is considered obese. Such information doesn’t suggest the risk of developing obesity, which is revealed by studying a population over specific periods of time. So in the latest study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, scientists tracked a group of 7738 children, some of whom were overweight or obese, and some who were normal weight, from 1998 (when they were in kindergarten) to 2007 (when they were in ninth grade). They found that the 14.9% of five-year-olds who were overweight at kindergarten were four times more likely to become obese nearly a decade later than five-year-olds of a healthy weight. During the study, the researchers measured the children’s height and weight seven times, which allowed them to record the incidence of obesity almost yearly. Overall, since most of the 23(29) children (6807) were normal weight at the start of the study, the children’s risk of becoming obese decreased by 5.4% during the kindergarten year and by 1.7% between the fifth and eighth grades. But the five-year-olds who were overweight, defined as having a body mass index (BMI) within the 85th percentile for their age group were significantly more likely to become obese, which the scientists defined as a BMI within the 95th percentile of their age group as time went on. Among kids who became obese between the ages of five and 14, about half had been overweight in the past and 75% were in a high BMI percentile at the start of the study. Obesity is connected to a high risk of chronic conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, and stroke among adults, and young children who spend more years overweight or obese may be putting themselves at even higher risk of these diseases, the scientists say. The study highlights the dynamic between early weight gain and obesity, and the researchers say future work should focus on understanding what contributes to a child becoming overweight so early in life. The results suggest that education about weight gain and obesity prevention efforts may need to start earlier with families of young children, before youngsters become locked in a condition that’s difficult to change. Reading Passage #2 – (Homework Assignment Practice Reading) Premature Babies: Talking to Them Improves their Language Development By Alice Park – February 10, 2014 Language and conversation is our lifeblood. And that’s even true, scientists say, if one of the “speakers” may not have fully developed language skills. Led by Dr. Betty Vohr, a professor of pediatrics at Brown University, researchers found that premature babies in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) benefited when their mothers spoke to them in attempts to engage them in conversation, compared to if their mothers simply stroked them or if the babies were primarily around nurses who talked about or around them but didn’t address the babies directly. Vohr and her team studied 36 preterm infants and made 16-hour recordings when they were 32 weeks and 36 weeks old. The 32-week-old babies were born eight weeks before their mother’s due date, and the 36-week-old infants were delivered four weeks shy of their expected birth date. When the infants were 7 and 18 months old, the researchers tested their cognitive and language skills, including their ability to communicate by receiving and expressing themselves, first with vocalizations and eventually with their first words. For every increase in 100 words that adults spoke to the preterm infants, the scientists found a two-point increase in their language scores at 18 months, and a half-point increase in their expressive communication score. 24(29) Previous studies have documented that hearing and responding to speech is critical for normal language development, and that premature babies are at higher risk of language delays compared to babies born at term.. So the possibility that something as simple as having parents speak to their babies, even in the isolette in a NICU, can minimize such potential language delays is exciting. The results are intriguing because Vohr and her team were able to pinpoint what type of communication seemed to make a difference. They found that actually engaging the baby by addressing the infant – ‘Hi Joshua, mommy’s here’ – did better at 18 months than those whose mothers held them, but didn’t speak as much, or those who were cared for by nurses who talked mostly about their vital signs and other medical issues to other health care personnel. Vohr says that although preterm babies can’t communicate with language, they do respond to attempts to engage them with vocalizations. Studies also showed that they turn instinctively to their mother’s voice after they are born, which presumably is familiar from their time in the womb. “Our conclusion is that it’s really important for moms to come into the NICU, and for them to talk to their babies,” says Vohr. What’s more exciting, she says, is that while most of NICU care involves the latest technology and expensive equipment, having mom or dad talk to their babies doesn’t cost anything. “This just really involves talking to moms and informing them that you have an important role here, and you can make a big difference for your baby,” says Vohr. Departmental Mid-Term Assessment The Road to Ivory is Stained with Blood By Michael Dobie The ongoing slaughter of African elephants, in service to the worldwide trade in illegal ivory, is shameful and heartbreaking. However, a series of recent events here and abroad is creating optimism that progress can be made in the fight to stop the killing. The United States has banned nearly all trading of ivory and crushed six tons of seized ivory last year, prompting China and France to do the same. The United States also was one of 46 nations at a London conference earlier this month that called for a global crackdown on wildlife trafficking that kills tens of thousands of elephants, rhinos and other endangered species every year. Time will tell whether those words lead to actions that help solve this serious problem, because the notion of doing nothing is unacceptable. Elephant tusks can be used in jewelry and carvings. As such, an estimated 35,000 African elephants are killed yearly by poachers; once numbering in the millions, the population now is about 400,000. One species, the African forest elephant, has declined 76 percent since 2002 and could be extinct in a decade. And it's not just elephants at risk. Hundreds of African park rangers have been killed in the last few years. 25(29) As consumers, we play a role in this. New York City's ivory market is the largest in the nation, and the United States is one of world's prime destinations for ivory, behind only China in some estimates. Elephant ivory trade was banned worldwide by treaty in 1989, which temporarily slowed the killing, but the bloody business is back in full swing. Terrorist organizations and rebel groups are now raising funds via the illegal harvest of ivory. The United Nations estimates the global trade at more than $30 million a year. The 1989 action and the new U.S. ban were well-intentioned, but problems with both limit their effectiveness. The first ban exempted ivory harvested from elephants killed before 1989, an exemption partially continued under the U.S. ban. But determining the age of old ivory is notoriously difficult; often it comes down to the seller's word. Some sellers stain ivory to make it look older. Allowing some legal trade of ivory has masked the illegal trade and allowed it to flourish. As for the U.S. ban, it came via executive action by President Barack Obama, not legislation, and can be undone by the next chief executive. These problems are addressed by state legislation being offered by New York congressman Robert Sweeney. It calls for a complete ban on ivory sales and tough penalties to match. Given the size of the New York market, its effect could be dramatic. It's a strong complement to the already existing federal ban on ivory and deserves legal passage. And it could serve as a model for other states. Wildlife Conservation Society officials say groups in eight other states -including California and Florida -- are interested in supporting similar legislation. The good news appears to be that the world finally is waking up to the magnitude of this crisis. But saving elephants is not just a matter of government action. That's where we as individuals come in. We need to understand that when we buy ivory, we're helping to make extinct the largest and most majestic land animal on earth. So it's time to ask yourself about stopping the harvesting of ivory from our planet’s precious wildlife: Do you care? FINAL ASSESSMENT READING (Department Reading Summary Final Reading) Paying a Price for Loving Red Meat By JANE E. BRODY There was a time when red meat was a luxury for ordinary Americans, or was at least something special: cooking a roast for Sunday dinner, ordering a steak at a restaurant. Not anymore. Meat consumption has more than doubled in the United States in the last 50 years. Now a new study of more than 500,000 Americans has provided the best evidence yet that our affinity for red meat has exacted a hefty price on our health and limited our longevity. The study found that, other things being equal, the men and women who consumed the most red and processed meat were likely to die sooner, especially from one of our two leading killers, heart disease and cancer, than people who consumed much smaller amounts of these foods. Results of the decade-long study were published in the March 23 issue of The Archives of 26(29) Internal Medicine. The study, directed by Rashmi Sinha, a nutritional doctor at the National Cancer Institute, involved 322,263 men and 223,390 women ages 50 to 71 who participated in the National Institutes of Health-AARP Diet and Health Study. Each participant completed detailed questionnaires about diet and other habits and characteristics, including smoking, exercise, alcohol consumption, education, use of supplements, weight and family history of cancer. During the decade, 47,976 men and 23,276 women died, and the researchers kept track of the timing and reasons for each death. Red meat consumption ranged from a low of less than an ounce a day, on average, to a high of four ounces a day, and processed meat consumption ranged from at most once a week to an average of one and a half ounces a day. The increase in mortality risk tied to the higher levels of meat consumption was described as “modest,” ranging from about 20 percent to nearly 40 percent. But the number of excess deaths that could be attributed to high meat consumption is quite large given the size of the American population. The new findings suggest that over the course of a decade, the deaths of one million men and perhaps half a million women could be prevented just by eating less red and processed meats, according to estimates prepared by Dr. Barry Popkin, who wrote an editorial accompanying the report. To prevent premature deaths related to red and processed meats, Dr. Popkin suggested in an interview that people should eat a hamburger only once or twice a week instead of every day, a small steak once a week instead of every other day, and a hot dog every month and a half instead of once a week. In place of red meat, non-vegetarians might consider poultry and fish. In the study, the largest consumers of “white” meat from poultry and fish had a slight survival advantage. Likewise, those who ate the most fruits and vegetables also tended to live longer. A question that arises from observational studies like this one is whether meat is in fact a hazard or whether other factors associated with meat-eating are the real culprits in raising death rates. The subjects in the study who ate the most red meat had other less-than-healthful habits. They were more likely to smoke, weigh more for their height, and consume more calories and more total fat and saturated fat. They also ate less fruits, vegetables and fiber; took fewer vitamin supplements; and were less physically active. Poultry and fish contain less saturated fat than red meat, and fish contains omega-3 fatty acids that have been linked in several large studies to heart benefits. For example, men who consume two servings of fatty fish a week were found to have a 50 percent lower risk of cardiac deaths, and in the Nurses’ Health Study of 84,688 women, those who ate fish and foods rich in omega-3 fatty acids at least once a week cut their coronary risk by more than 20 percent. 27(29) SCORING RUBRICS FOR COMMUNICATION AND LITERACY SKILLS: WRITTEN SUMMARY EXERCISE (MTEL) Summary Scoring Rubric Score Point Description 4 The response accurately and clearly conveys all of the main ideas and significant details of the original passage. It does not introduce information, opinion, or analysis not found in the original. Relationships among ideas are preserved. The response is concise while providing enough statements of appropriate depth and specificity to convey the main ideas and significant details of the original passage. The response is written in the candidate's own words, clearly and coherently conveying main ideas and significant details. The response shows excellent control of grammar and conventions. Sentence structure, word choice, and usage are precise and effective. Mechanics (i.e., spelling, punctuation, and capitalization) conform to the standard conventions of written English. 3 The response conveys most of the main ideas and significant details of the original passage, and is generally accurate and clear. It introduces very little or no information, opinion, or analysis not found in the original. Relationships among ideas are generally maintained. The response may be too long or too short, but generally provides enough statements of appropriate depth and specificity to convey most of the main ideas and significant details of the original passage. The response is generally written in the candidate's own words, conveying main ideas and significant details in a generally clear and coherent manner. The response shows general control of grammar and conventions. Some minor errors in sentence structure, word choice, usage and mechanics (i.e., spelling, punctuation, and capitalization) may be present. 2 The response conveys only some of the main ideas and significant details of the original passage. Information, opinion, or analysis not found in the original passage may substitute for some of the original ideas. Relationships among ideas may be unclear. The response either includes or excludes too much of the content of the original passage. It is too long or too short. It may take the form of a list or an outline. The response may be written only partially in the candidate's own words while conveying main ideas and significant details. Language not from the passage may be unclear and/or disjointed. The response shows limited control of grammar and conventions. Errors in sentence structure, word choice, usage, and/or mechanics (i.e., spelling, punctuation, and capitalization) are distracting. 1 The response fails to convey the main ideas and details of the original passage. It may consist mostly of information, opinion, or analysis not found in the original. The response is not concise. It either includes or excludes almost all the content of the original passage. The response is written almost entirely of language from the original passage or is written in the candidate's own words and is confused and/or incoherent. 28(29) The response fails to show control of grammar and conventions. Serious errors in sentence structure, word choice, usage, and/or mechanics (i.e., spelling, punctuation, and capitalization) impede communication. The response is unrelated to the assigned topic, illegible, primarily in a language otherthan English, not of sufficient length to score, or merely a repetition of the assignment. There is no response to the assignment. U B 29(29)