[J-99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108,... IN THE SUPREME COURT OF PENNSYLVANIA

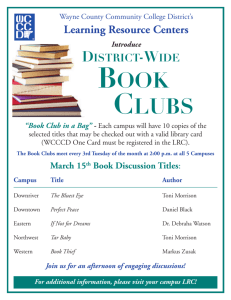

advertisement