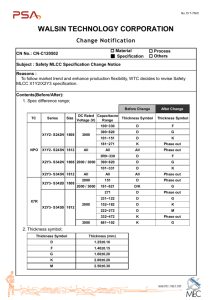

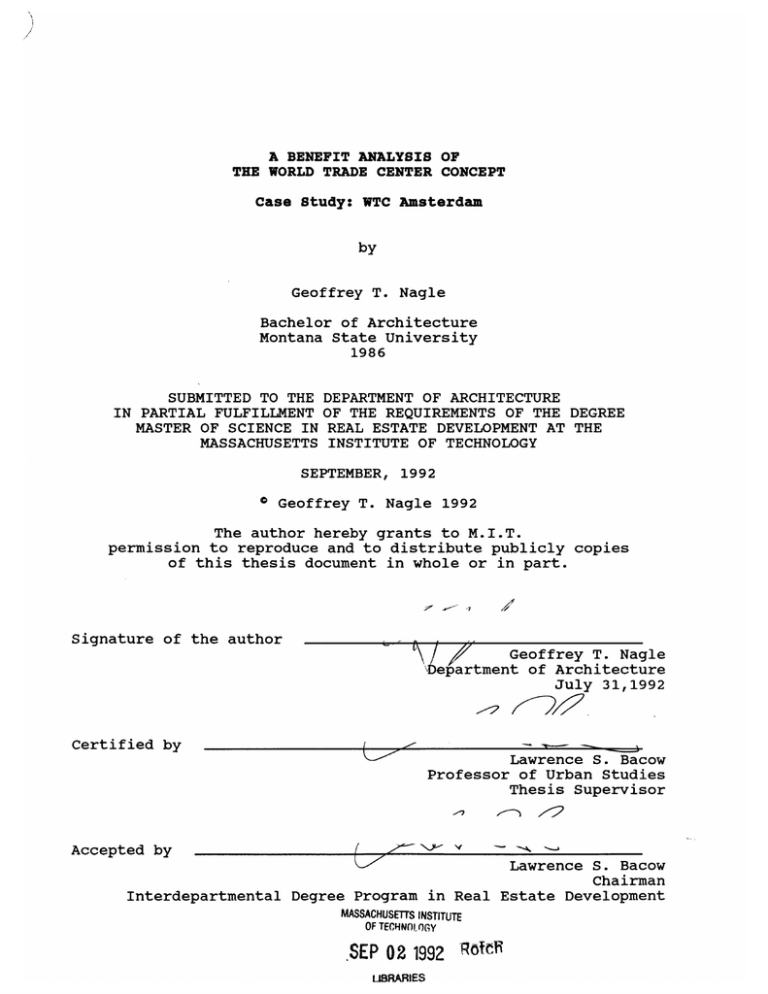

A OF Study: WTC Amsterdam Geoffrey T. Nagle

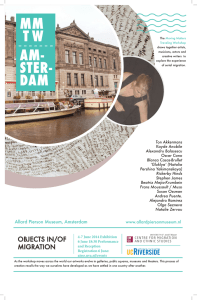

advertisement