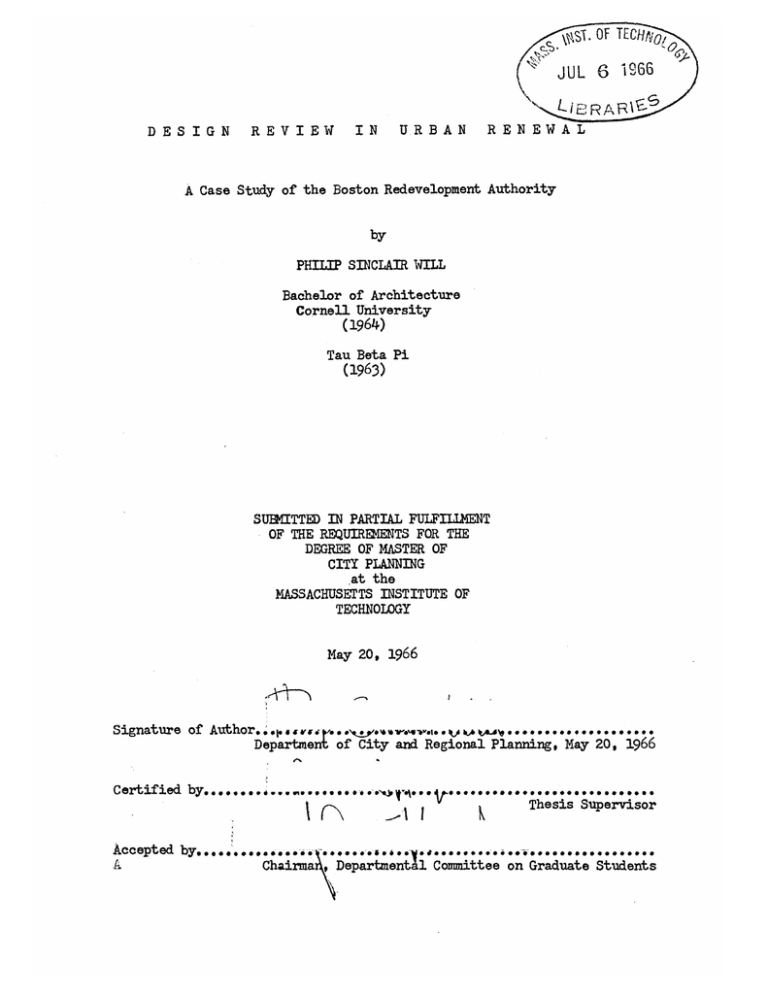

JUL 6 1966

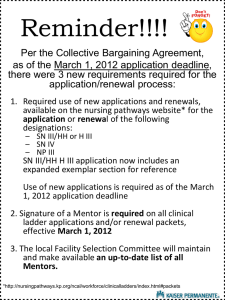

advertisement