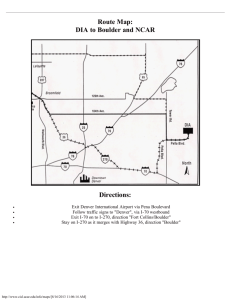

1976 13 JUL by

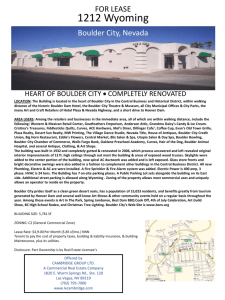

advertisement