File

advertisement

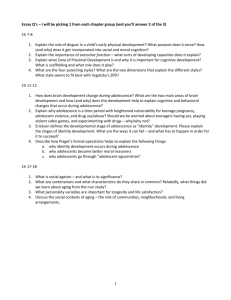

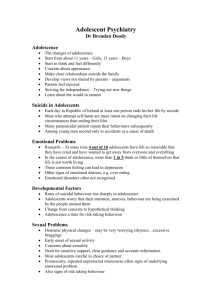

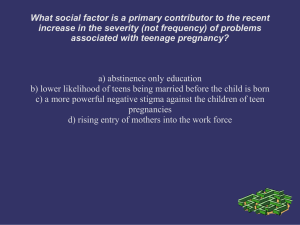

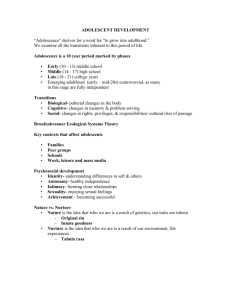

GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT Part 3 Millenium Development Goals http://nursethechild.weebly.com/ Specific Objectives: By the end of this lecture, the student will be able to: • Identify the importance of growth and development. • Define growth and development. • Mention the principles of growth and development. • List factors affecting growth and development. • Mention types of growth and development. • Identify the stages of development. Adolescent Development in Context Significant Interpersonal Relationships During Adolescence Parent-Adolescent Relationships: Primary Questions How do parent-adolescent relationships change over the course of adolescence? What is the impact of adolescence on the family? How does adolescent adjustment vary as a function of variations in the parentadolescent relationship? What is the impact of the family on the adolescent? Changes in Family Relationships: Autonomy As children enter adolescence, they will strive toward greater autonomy Autonomy refers to endorsing one’s actions and viewing them as an expression of one’s self Establishing autonomy involves becoming a self-governing person within relationships Adolescents’ early attempts at establishing autonomy frequently precipitate conflict between parents and teenagers During adolescence, a shift occurs toward a more egalitarian relationship Changes in Family Relationships: Conflict Frequent, high-intensity, angry fighting is not normative during adolescence There is a genuine increase in bickering and squabbling between parents and teenagers during the early adolescent years Much parent-adolescent conflict results from changes in the adolescent’s reasoning about the legitimacy of parental authority. Matters that parents see as moral or practical issues, adolescents see as questions of personal choice, and they begin to challenge parental authority when they believe it is not legitimate Changes in Family Relationships: Harmony Subjective feelings of closeness decrease during adolescence, as does the amount of time parents and teenagers spend together Although perceptions of relationships often remain warm and supportive, both adolescents and parents report less frequent expressions of positive emotions Children who had warm, close relationships with their parents during childhood are likely to remain close and connected to their parents during adolescence, even though the frequency and quantity of positive interactions may be somewhat diminished Influence of Parenting on Adjustment Four patterns of parenting: Authoritative (responsive and demanding) Permissive (responsive but not demanding) Authoritarian (demanding but not responsive) Indifferent (neither responsive nor demanding) Influence of Parenting on Adjustment Adolescents from authoritative homes are more responsible, more self-assured, and more socially competent Adolescents from authoritarian homes are more dependent, more passive, less socially adept, less confident, and less intellectually curious Adolescents reared in permissive homes are often less mature, less responsible, more vulnerable to peer pressure, and less able to assume positions of leadership Adolescents reared in indifferent homes are disproportionately impulsive, more likely to be involved in delinquent behavior, and more likely to experiment with drugs and alcohol Influence of Parenting on Adjustment Across a variety of outcomes, adolescents fare best in homes that strike a balance between autonomy and connectedness Such homes are characterized by a climate of warmth, in which they are encouraged both to be “connected” to their parents and to express their own individuality Such homes employ joint decision-making, whereby the adolescent plays an important role in the decision-making process but parents remain involved in the eventual resolution Friendships In adolescence, friendships are the primary contexts for the acquisition of skills – ranging from social competencies to cognitive abilities – and socio-cultural values and expectations In adolescence, perceptions of parents as primary sources of support decline and perceived support from friends increases High quality friendships become increasingly important as sources of support for adolescents experiencing emotional problems, though they do not substitute for parental support Romantic Relationships Romantic interests are both normal and important during adolescence Many adolescents regard bring in a romantic relationship as central to “belonging” and status in their peer group This link is transactional: peer networks support early romantic coupling, and romantic relationships facilitate connections with other peers Although early dating and sexual activity are risk factors for subsequent social and emotional difficulties, high quality romantic relationships are associated with enhanced feelings of self-worth The developmental significance of romantic relationships depends more heavily on the behavioral, cognitive, and emotional processes that occur in the relationship than on the age of initiation and degree of dating activity that an adolescent experiences Interpersonal Contexts and the Psychosocial Tasks of Adolescence Independence and Interdependence Adolescence is a period of tension between two developmental tasks: 1) increasing connections to others beyond the family and conforming to societal expectations 2) attaining individual competence and autonomy from the influence of others Successful adolescent development involves separating oneself from others while simultaneously forming connections and close relationships Developing a Sense of Independence Although the development of independence is often cast as an individual accomplishment, it is embedded in the interpersonal contexts of family and peer relationships Independence is both a process and an outcome Independence is valued differently in different cultural contexts There are two broad types of independence: emotional and behavioral Emotional Independence Developing emotional independence involves increases in adolescents’ subjective sense of independence, especially in relation to parents In early adolescence, this is achieved in part by separating oneself from and arguing with one’s parents; through this process the relationship is transformed and the adolescent develops both a new behavioral repertoire and a new image of his or her parents In this sense, developing emotional independence is not primarily an individual transformation but rather an interpersonal transformation in which patterns of parent-child interaction are mutually (if unwillingly) renegotiated This transformative process yields three outcomes: 1) A changed adolescent who now views him- or herself in a different light 2) Changed parents who now view their adolescent (and perhaps themselves) in a different light 3) A changed, more egalitarian parent-child relationship Behavioral Independence Developing behavioral independence involves increases in adolescents’ capacity for independent decision-making and self-governance Parents facilitate the development of behavioral independence in four ways: 1) By modeling effective decision-making 2) By encouraging independent decision-making in the family context 3) By rewarding independent decision-making outside the family context 4) By instilling in the adolescent a more general sense of self-efficacy through the use of parenting that is both responsive and demanding Developing a Sense of Interdependence There are two psychosocial goals comprising the task of interdependence: 1) Attachment 2) Intimacy Attachment in adolescence is part of Achieving interdependence a developmental attachment process begun at birth Attachment refers to a parent-child connection – begun in infancy – that supports children’s efforts to feel safe from threatening circumstances and to be regulated emotionally Attachment to parents or caregivers forms the substrate on which other attachments are built Representations of parent-child attachment relationships organize expectations and behaviors in later relationships Healthy parent-child relationships expose children to components of effective relating, such as empathy, reciprocity, and self-confidence Attachment Maintaining interdependence in adolescence involves redistributing the functions of relationships Perceptions of parents as primary sources of support decline and perceived support from friends increases In this process, attachment is transformed from a relationship where one partner (the parent) cares for another (the child) to one characterized by mutual caregiving between two partners (friends or romantic partners) The quality of early attachment relationships predicts the quality of all future relationships For adolescents to achieve interdependence, they must build on earlier secure relationship patterns to form and maintain further stable relationships Intimacy Intimacy is an interpersonal process within which two interaction partners experience and express feelings, communicate verbally and nonverbally, satisfy social motives, reduce social fears, talk and learn about themselves and their unique characteristics, and become “close” As a psychosocial task of adolescence, intimacy refers to experiencing this mutual openness and responsiveness in at least some relationships with peers Concepts of friendship first incorporate notions of intimacy in early adolescence Adolescents become increasingly capable of intimate relationships as they develop a more sophisticated understanding of social relations, and as they hone their ability to infer the thoughts and feelings of others Intimacy In peer relationships, spending larger amounts of time with peers and correspondingly less time with adults contributes to adolescents’ development of intimacy by increasing comfort with peers and encouraging self-disclosure as well as openness to others’ self-revelations Shared interest in mastering the distinctive social challenges of adolescence also stimulates a desire to communicate with peers The superficial sharing of activities that sufficed between childhood friends is supplanted, during adolescence, by the potential for mutual responsiveness, concern, loyalty, trustworthiness, and respect between adolescent friends Friendship in adolescence meets a basic psychological need to overcome loneliness and develop a sense of belonging Conclusions Adolescent development, though largely characterized by biological changes, cannot be understood outside of the interpersonal contexts in which it occurs Perceptions and expectations forged through parent-child relationships mediate the psychological and behavioral impact of pubertal changes and provide a foundation on which all adolescent interactions and relationships are based By being mindful of the changes that occur during adolescence and the ways in which parent-child interactions influence these changes, parents will be better equipped to interact with their adolescents in ways that equip them with the skills they require to successfully navigate these transitions and maximize positive developmental outcomes for Health Promotion I. Adolescent Safety 1. Accidents, most commonly those involving motor vehicles, are the leading cause of death among adolescents. Management: - Parents need to have the courage to insist on emotional maturity rather than age as a qualification for obtaining a driver’s license 2. Drowning is another chief accident of adolescence, even though it is largely preventable. Management: - Teaching water safety, such as not swimming alone or when tired, is as important as teaching the mechanics of swimming 3. The second most common cause of death among adolescents is homicide, r/t to the easy availability of guns to teenagers. - Gang violence and the desire to protect them from this add to this problem 4. Accidental gunshot injuries increase in early adolescence, often for the same reason that drowning increases: youngsters want to impress friends. 5. Athletic injuries tend to occur during adolescence because of the vigorous level of competition that occurs. - Overuse injuries result from poor conditioning Suicide Prevention 30 Suicide Prevention Introduction Objectives: The scope and importance of suicide prevention The negative impact of myths and misinformation How to identify a person at risk-signs symptoms How to effectively communicate with a suicidal person How to gain information to help the person How to refer a person for evaluation and treatment 31 Suicide Prevention Myths and Misinformation Myth: Asking about suicide will plant the idea in a person’s head. Reality: Asking a person about suicide does not create suicidal thoughts any more than asking about chest pain causes angina. The act of asking the question simply gives the person permission to talk about his or her thoughts or feelings. 32 Suicide Prevention Myths and Misinformation Myth: There are talkers and there are doers. Reality: Most people who die by suicide have communicated some intent. Someone who talks about suicide gives the guide and/or clinician an opportunity to intervene before suicidal behaviors occur. 33 Suicide Prevention Myths and Misinformation Myth: If somebody really wants to die by suicide, there is nothing you can do about it. Reality: Most suicidal ideas are associated with the presence of underlying treatable disorders. Providing a safe environment for treatment of the underlying cause can save a life. The acute risk for suicide is often time-limited. If you can help the person survive the immediate crisis and overcome the strong intent to die by suicide, you have gone a long way toward promoting a positive outcome. 34 Suicide Prevention Myths and Misinformation Myth: He/she really wouldn't commit suicide because… he just made plans for a vacation she has young children at home he made a verbal or written promise she knows how dearly her family loves her Reality: The intent to die can override any rational thinking. “No Harm” or “No Suicide” contracts have been shown to be ineffective from a clinical and management perspective. A person experiencing suicidal ideation or intent must be taken seriously and referred to a clinical provider who can further evaluate their condition and provide treatment as appropriate. 35 Suicide Prevention Operation S.A.V.E. Operation S. A. V. E. will help you act with care and compassion if you encounter a person who is suicidal. The acronym “SAVE” summarizes the steps needed to take an active and valuable role in suicide prevention. Signs of suicidal thinking Ask questions Validate the person’s experience Encourage treatment and Expedite getting help 36 Suicide Prevention Operation S.A.V.E. Importance of identification Suicidal individuals are not always easy to identify. There is no single profile to guide recognition. There are a number of warning signs and symptoms. Some of the signs of suicidality are obvious, but others are not. Signs and symptoms do not always mean the person is suicidal but: When you recognize signs, it is important to ask the person how they are doing because they may mean that they are in trouble. 37 SAD PERSONS: Sex: male Age: young, elderly Depression Previous suicide attempts Ethanol and other drugs Reality testing/ Rational thought (loss of) Social support lacking Organized suicide plan No spouse Sickness/ Stated future intent Suicide Prevention Signs of suicidal thinking Signs and Symptoms: Threatening to hurt or kill self Looking for ways to kill self Seeking access to pills, weapons or other means Talking or writing about death, dying or suicide Hopelessness Rage, anger Seeking revenge Acting reckless or engaging in risky activities 39 Suicide Prevention Signs of suicidal thinking Feeling trapped Increasing drug or alcohol abuse Withdrawing from friends, family and society Anxiety, agitation Dramatic changes in mood No reason for living, no sense of purpose in life Difficulty sleeping or sleeping all the time Giving away possessions Increase or decrease in spirituality 40 Suicide Prevention Ask questions To effectively determine if a person is suicidal, one needs to interact in a manner that communicates concern and understanding. As well, one needs to know how to manage personal discomfort(i.e., anxiety, fear, frustration, personal, cultural or religious values) in order to directly address the issue. Know how to ask the most important question The most difficult S. A. V. E. step is asking the most important question of all – “Are you thinking of killing yourself.” 41 Suicide Prevention Ask questions How DO I ask the question? DO ask the question after you have enough information to reasonably believe the person is suicidal. DO ask the question in such a way that is natural and flows with the conversation. DON’T ask the question as though you are looking for a “no” answer. “You aren’t thinking of killing yourself are you?” 42 Suicide Prevention Ask questions Things to consider when you talk with the person: Remain calm Listen more than you speak Maintain eye contact Act with confidence Do not argue Use open body language Limit questions to gathering information casually Use supportive and encouraging comments Be as honest and “up front” as possible 43 Suicide Prevention Validate the veteran’s experience Validation means: Show the person that you are following what they are saying Accept their situation for what it is You are not passing judgment Let them know that their situation is serious and deserving of attention Acknowledge their feelings Let him or her know you are there to help 44 Suicide Prevention Encourage treatment and Expedite getting help For the cooperative person: Tips for encouraging treatment: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Explain that there are trained professionals available to help them. Explain that treatment works. Explain that getting help for this kind of problem is no different than seeing a specialist for other medical problems. Tell them that getting treatment is his or her right. If they tell you that they have had treatment before and it has not worked, try asking: “What if this is the time it does work?” 45 Suicide Prevention Encourage treatment and Expedite getting help Tips for expediting a referral: 1. 2. 3. Assist the person in getting to a care facility by personally taking them or arranging for transportation. Call the VA Suicide Hotline number with the veteran to get a referral started. 1-800-273-TALK – push “1”. Call the local facility Suicide Prevention Coordinator – you make access this person from the information desk at any VA. 46 Suicide Prevention Encourage treatment and Expedite getting help For uncooperative people or those in immediate crisis: As you encourage the person to seek help, some situations may involve people who are hostile and aggressive. Here are some useful safety guidelines for working with seriously and acutely distressed people: [These rules are both for the person’s safety and yours.] 47 Suicide Prevention Encourage treatment and Expedite getting help Any time a person has a weapon or object that can be used as a weapon – call for help. If a person tells you that they have overdosed on pills or other drugs or there are signs of physical injury – call for help. In addition to calling for help, if you are confronted with a hostile or armed person, leave the area and attempt to isolate the person. If the person leaves your area, attempt to observe his or her direction of movement from a safe distance and report your observations as soon as authorities arrive on scene. 48 Suicide Prevention Operation S. A.V. E. SUMMARY Operation S. A. V. E. can save lives by helping you become aware of: Signs of suicidal behavior and giving you the skills to: Ask questions Validate the person’s experience and to Encourage treatment and Expedite getting help 49 Suicide Prevention Operation S. A.V. E. By participating in this training you have learned: The scope of the problem of suicides among the veteran population The importance of suicide prevention The negative impact of myths and misinformation How to identify a person who may be at risk Some of the signs and symptoms of suicidal thinking How to effectively communicate with a suicidal person How to gain information to help the person How to refer someone for evaluation and treatment 50 Suicide Prevention Operation S. A.V. E. There are plenty of resources available to someone who is suicidal but we need you to partner with us in identifying the suicidal person and getting them into treatment. 51 8937603/06 Hello crisisline 2333 G or 211 S II. Nutritional Health 1. Adolescents experience so much growth that they may always feel hungry 2. If adolescent’s eating habits are unsupervised, they will tend to eat faddish or quick snack foods rather more nutritionally sound ones 3. Some may turn away from the five pyramid food groups to eat great quantities of sweets, soft-drinks, or empty calorie snacks which leaves them poorly nourished despite the large intake 4. Adolescents who are slightly obese because of prepubertal changes may begin to low-calorie or starvation diets to lose excess weight 5. An adolescent needs an increased number of calories to maintain a rapid period of growth 6. Because vegetables generally contain fewer calories than meat, adolescents need to consume large amounts of them to achieve an adequate caloric intake with a vegetarian diet 7. Athletes need more carbohydrate or energy than do people who do not engage in strenuous activity, and the source of carbohydrate that best sustains athletes comes from the breakdown of glycogen because this supplies slow steady release of glucose 8. As a rule, the goals of nutrition that are best for everyone, such as eating a well-balanced diet, are also best for athletes, rather than diets that interfere with carbohydrate, fluid or fat intake III. Adolescent Development in Daily Activities 1. Maintaining adequate sleep, hygiene and exercise are important and should become the adolescent’s responsibility rather than the parents’. 2. Parents can, however, encourage adolescents to engage in healthy patterns of living-primarily to role modeling. 3. Dress and Hygiene: They are capable of total self-care and because of their body awareness, they may even be overly conscientious about personal hygiene and appearance 4. Care of teeth: They are generally very conscientious about tooth brushing because of the fear of developing bad breath 5. Sleep: Although it is widely believed that adults need 8h of sleep a night, some need more and others can adjust to considerably less - Many adolescents attempt to get by with too little sleep, because they are constantly busy and because staying up late is a symbol of the adult status they long for 6. Exercise: Adolescents need exercise everyday to maintain muscle tone and to provide an outlet of tension. -Although they are constantly on the go, they often receive little real exercise IV. Healthy Family Functioning 1. Early adolescents may have many disagreements with parents that seem partly from wanting more independence and partly from being so disappointed in their bodies 2. It is frustrating for children to be told by parents that they are too old to behave in a certain manner when they still don’t feel or look older 3. At other times, just when they begin to accept their maturing appearance, parents tell them they are too young to do something 4. Adolescents find even more fault in their parents and wonder how they can exist with their outdated ideas 5. They have trouble respecting parents who are so obviously imperfect - School marks may slump as a reflection of this “fallen angel” syndrome - These adolescents may follow health advice poorly because they view health care personnel in the same light 6. By the time they are 16, adolescents generally become more willing to listen and to talk about problems Adolescents are not only large in number but also the citizens and workers of tomorrow. More than 33% of the disease burden and almost 60% of premature deaths among adults can be associated with behaviors or conditions that began or occurred during adolescence. Thus focusing attention on diseases experienced during adolescence and on risk factors rooted in adolescence makes sense. In line with the global policy changes on adolescents and youth, the DOH created the Adolescent and Youth Health and Development Program (AYHDP) which is lodged at the National Center for Disease Prevention and Control (NCDPC) specifically the Center for Family and Environmental Health (CFEH). The program is an expanded version of Adolescent Reproductive Health (ARH) element of Reproductive Health which aims to integrate adolescent and youth health services into the health delivery systems. Developmental theory Freud theory (sexual development). Piaget theory (cognitive development ). Erikson theory (psychosocial development). Freud theory (sexual development) Infancy stage Toddler stage Preschool stage School-age stage Adolescence stage Oral-sensory stage Anal stage Genital stage Latency Stage Pubertal stage Piaget theory (cognitive development Infancy stage Toddler stage Preschool stage School-age stage Adolescence stage Up to2 years sensori -motor 2-3 years pre-conceptual phase. Up to 4years pre-conceptual phase. 7-12 years concrete-operational. 12-15 years preoperational formal operations 15 years - through life formal operations Erikson theory (psychosocial development) Trust versus mistrust. Infancy stage Toddler stage Preschool stage School-age stage Adolescence stage Autonomy and self esteem versus shame and doubt. Initiative versus guilt. Industry versus inferiority. Identity and intimacy versus role confusion.