Maclean and District Bowling Club Co

advertisement

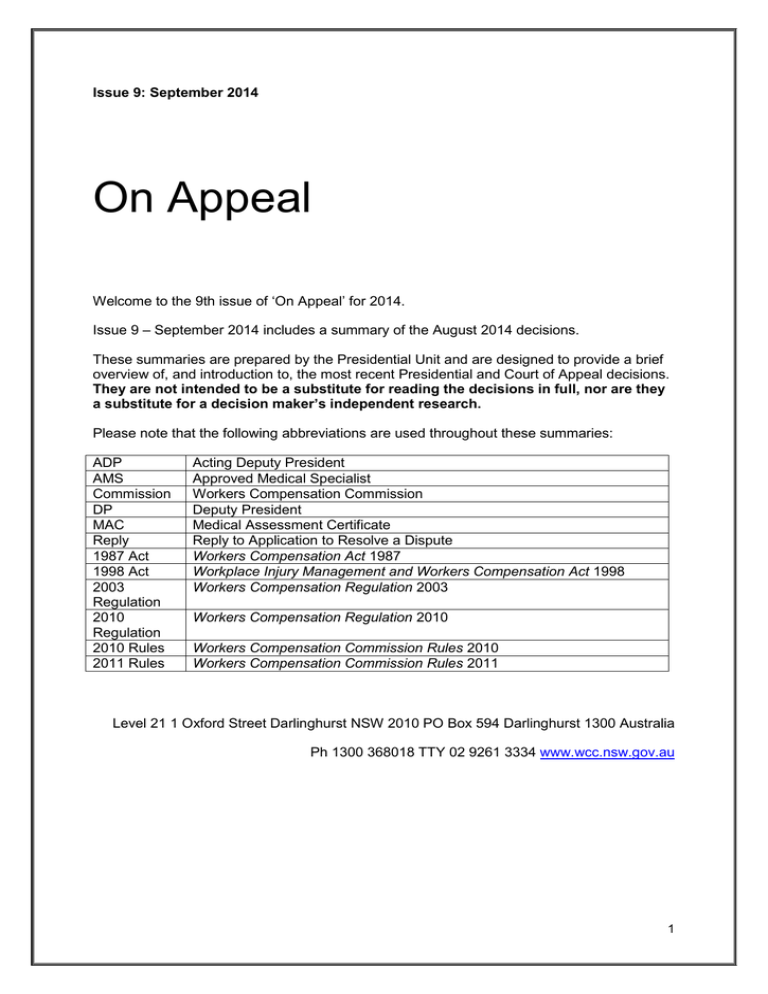

Issue 9: September 2014 On Appeal Welcome to the 9th issue of ‘On Appeal’ for 2014. Issue 9 – September 2014 includes a summary of the August 2014 decisions. These summaries are prepared by the Presidential Unit and are designed to provide a brief overview of, and introduction to, the most recent Presidential and Court of Appeal decisions. They are not intended to be a substitute for reading the decisions in full, nor are they a substitute for a decision maker’s independent research. Please note that the following abbreviations are used throughout these summaries: ADP AMS Commission DP MAC Reply 1987 Act 1998 Act 2003 Regulation 2010 Regulation 2010 Rules 2011 Rules Acting Deputy President Approved Medical Specialist Workers Compensation Commission Deputy President Medical Assessment Certificate Reply to Application to Resolve a Dispute Workers Compensation Act 1987 Workplace Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998 Workers Compensation Regulation 2003 Workers Compensation Regulation 2010 Workers Compensation Commission Rules 2010 Workers Compensation Commission Rules 2011 Level 21 1 Oxford Street Darlinghurst NSW 2010 PO Box 594 Darlinghurst 1300 Australia Ph 1300 368018 TTY 02 9261 3334 www.wcc.nsw.gov.au 1 Table of Contents Presidential Decisions: Maclean and District Bowling Club Co-operative Ltd v Green [2014] NSWWCCPD 53 .. 3 Disease; lung cancer; passive smoking; whether employment in the club and hotel industry was employment to the nature of which the disease of lung cancer was due; whether employment a substantial contributing factor to the injury; whether lung cancer is a disease which is of such a nature as to be contracted by a gradual process; failure to consider relevant evidence; failure to engage with competing evidence; failure to properly determine issues in dispute; ss 4(b)(i) and 15(1) of the 1987 Act; calculating time to appeal; appeal filed out of time; extension of time to appeal; s 352(4) of the 1998 Act; Pt 16 r 16.2(2) of the 2011 Rules ........................................................................................... 3 McGowan v Secretary, Department of Education and Communities [2014] NSWWCCPD 51 ................................................................................................................... 7 Boilermaker’s deafness; claim for lump sum compensation for binaural hearing loss; dispute as to the nature and extent of the hearing loss; role of Commission and AMSs in such a dispute; consequence of finding that employment was employment to the nature of which the injury of boilermaker’s deafness was due; terms of referral to AMS; effect of invalid MAC; need for further medical assessment; s 17 of the 1987 Act; ss 293, 319, 321, 326 and 329 of the 1998 Act; whether orders made were interlocutory or final; extension of time to appeal; Pt 16 r 16.2(12) of the 2011 Rules ........................................................ 7 StateCover Mutual Ltd v Cameron [2014] NSWWCCPD 49 ............................................ 11 Claim for lump sum death benefit; disease contracted by a gradual process; melanoma; whether Arbitrator erred in relying on hearsay evidence; Commission not bound by the rules of evidence; Pt 15 r 15.2 of the 2011 Rules; whether employment a substantial contributing factor to the contraction of the disease; interpretation of special insurance provisions relating to occupational diseases; ss 4(b)(i), 15(1)(b) and 18(1) of the 1987 Act; relevance of s 151AB of the 1987 Act in a claim for workers’ compensation benefits ...... 11 Northern NSW Local Health District (Tweed Heads Hospital) v Conaghan [2014] NSWWCCPD 54 ................................................................................................................. 15 Section 4 the 1987 Act Act; injury arising out of or in course of employment; worker injured as a result of altercation with fellow worker and its consequences; challenge to finding that injury arose out of employment; consideration of decisions in Tarry v Warringah Shire Council [1974] WCR (NSW) 1 and Davis v Mobil Oil Australia Ltd (1988) 12 NSWLR 10 15 O v Nepean Blue Mountains Local Health District [2014] NSWWCCPD 52 ................... 18 Challenge to factual findings; assessment of expert evidence; application of the principles in Paric v John Holland (Constructions) Pty Ltd [1985] HCA 58; 62 ALR 85; 59 ALJR 844 ........................................................................................................................................ 18 Transgrid v Pryor [2014] NSWWCCPD 50 ....................................................................... 21 Injury; challenge to factual findings; inadequacy of reasons for decision ......................... 21 2 Maclean and District Bowling Club Co-operative Ltd v Green [2014] NSWWCCPD 53 Disease; lung cancer; passive smoking; whether employment in the club and hotel industry was employment to the nature of which the disease of lung cancer was due; whether employment a substantial contributing factor to the injury; whether lung cancer is a disease which is of such a nature as to be contracted by a gradual process; failure to consider relevant evidence; failure to engage with competing evidence; failure to properly determine issues in dispute; ss 4(b)(i) and 15(1) of the 1987 Act; calculating time to appeal; appeal filed out of time; extension of time to appeal; s 352(4) of the 1998 Act; Pt 16 r 16.2(2) of the 2011 Rules Roche DP 14 August 2014 Facts: The respondent worker, Susan Green, started work in the hotel and club industry in 1975, when she was 18 years of age. She worked as a bar attendant for several different clubs or hotels until she commenced with the appellant employer, Maclean and District Bowling Club Co-operative Ltd (the appellant/the Club), in December 1996. She continued with the appellant until she stopped work on 18 January 2002, when diagnosed with lung cancer. She did not formally resign until 4 September 2002. She alleged that all of her jobs in the liquor industry exposed her to environmental tobacco smoke from cigarettes. On 24 April 2012, Ms Green claimed lump sum compensation under ss 66 and 67 of the 1987 Act for impairments that resulted from her lung cancer and its complications. The appellant’s insurer, CGU Workers Compensation (NSW) Ltd, disputed liability. On 2 May 2014, the worker succeeded with her claim against the last employer who, the worker alleged, employed her in employment to the nature of which the disease was due. The Arbitrator accepted all of the worker’s employments in the liquor and club industry had been “employments to which the nature of the disease of lung cancer is due”. He added that it did not matter that Ms Green’s employment with the appellant may not have caused, aggravated or accelerated the “process”, provided that her employment (with the appellant) was of the class of employment to which the disease was due. Turning to whether “the employment concerned” had been a substantial contributing factor to the injury (s 9A of the 1987 Act), the Arbitrator said that the employment concerned related to the class of employment. He concluded that the environmental tobacco smoke Ms Green was exposed to in the liquor and club industry between 1975 and 2002 substantially contributed to the contraction by her of lung cancer and this contribution was real and of substance, even if the comparative contribution of cigarette smoking was significantly greater in dosage. He made that finding even in the event that Ms Green’s smoking was a major contributing factor to the contraction of that disease. The employer appealed. The issues in dispute in the appeal were whether the Arbitrator erred in: (a) finding that Ms Green’s employment was employment to the nature of which the disease was due; 3 (b) finding that Ms Green’s employment was a substantial contributing factor to the contraction of the disease; (c) failing to determine whether, for the purposes of s 15, Ms Green’s disease is a disease of gradual process or gradual onset, and failing to indicate at the arbitration that he would not determine that issue, thereby failing to afford the appellant procedural fairness, and (d) failing to give adequate reasons for his decision. Held: The Arbitrator’s determination of 2 May 2014 was revoked and the matter remitted to a different Arbitrator for re-determination. Discussion and findings 1. The appellant’s complaints come down to two main issues: first, the allegation that the Arbitrator’s decision was “clearly wrong”, which was based on an assertion that there was no expert evidence to support the claim, and, second, the allegation that the Arbitrator did not give adequate reasons for his decision [73]. 2. As explained by Meagher JA (Bathurst CJ and Hoeben JA agreeing) in CSR Timber Products Pty Limited v Weathertex Pty Limited [2013] NSWCA 49; the following are legally indispensable in a claim under s 4(b)(i): (a) that the worker contracted a disease in the course of employment and to which that employment was a contributing factor (s 4(b)(i)); (b) that the employment was a ‘substantial contributing factor’ to that injury (s 9A(1)); (c) that the disease was a disease of such a nature as to be contracted by a gradual process (s 15(1)); (d) that the worker made a claim for compensation in relation to that disease on a specific date (s 15(1)(a)(ii)), and (e) that the employer from whom compensation was claimed was the employer who last employed the worker in employment to the nature of which that disease was due (s 5(1)(b)) [74]. 3. The law on the meaning of the phrase “employment to the nature of which the disease was due” is well established (Smith v Mann [1932] HCA 30; Blatchford v Staddon & Founds (1927) A.C. 470 and Tame v Commonwealth Collieries Pty Ltd [1947] NSWStRp 9) [75]. 4. It was not accepted on appeal that there was no expert evidence in the present case which, if properly considered, was capable of supporting the finding that the worker’s employment, with the appellant, was employment to the nature of which the disease was due and that her employment (in the hotel and club industry over the years) was a substantial contributing factor to the injury. The evidence in support of the claim was found in several sources [78]. 5. Even in evidence based jurisdictions, compliance with the usual requirements for expert evidence “does not require strict compliance with each and every feature referred to by Heydon JA in Makita (Australia) Pty Ltd v Sprowles [2001] NSWCA 305; 4 to be set out in each and every report” (per Beazley JA (as her Honour then was) in Hancock v East Coast Timber Products Pty Ltd [2011] NSWCA 11 [85]. 6. In addition, there was expert evidence that, if accepted, supported a finding that the worker’s employment with the appellant, which undoubtedly exposed her to significant quantities of environmental tobacco smoke for several days per week over several years, was employment to the nature of which the disease of lung cancer is due and from which it could be inferred that her employment was a substantial contributing factor to her injury [102]. 7. It followed that the submission that there was no sound evidentiary basis for determining that Ms Green’s employment was employment to the nature of which the disease of lung cancer was due, and no evidence from which to conclude that her employment was a substantial contributing factor to the injury, was without foundation. There was evidence on the causation issue, including evidence from which to infer that Ms Green’s employment over many years in the hotel and club industry was a substantial contributing factor to the injury [105]. 8. However, the difficulty was that the Arbitrator did not analyse the issues and did not consider the majority of the evidence. For example, he made no relevant reference to the evidence from Associate Professor Bryant, no reference at all to the evidence in the research articles of Pirie and Taylor, submitted by the worker, or the report of Dr Ford, the treating cardiothoracic surgeon [106]. 9. Rather than considering the expert and lay evidence, and determining which he accepted and which he rejected, the Arbitrator merely expressed a conclusion. He accepted that all of Ms Green’s employments in the club and liquor industry had been employments to which the nature of the disease of lung cancer is due. That did not engage with the evidence nor determine the issues in dispute. That was an error in the process of fact finding because it involved a failure to examine all of the material relevant to the issue (Waterways Authority v Fitzgibbon [2005] HCA 57) [108]. 10. While it is correct that an arbitrator does not have to refer to all the evidence (Mifsud v Campbell (1991) 21 NSWLR 725), he or she should refer to the relevant evidence (Beale v Government Insurance Office of NSW (1997) 48 NSWLR 430). An Arbitrator is required to engage with the issues canvassed and to explain why one expert is accepted over the other (Taupau v HVAC Constructions (Queensland) Pty Limited [2012] NSWCA 293). The Arbitrator did not do that [109]. 11. Similar comments applied to the Arbitrator’s “analysis” of the substantial contributing factor issue. His “reasoning” essentially came down to one statement: after saying that he had particular regard to the submission that the worker’s cigarette smoking substantially outweighed the contribution made by environmental tobacco smoke, and noting expert evidence that the worker’s cigarette smoking dwarfed any contribution from environmental tobacco smoke, the Arbitrator concluded that the worker’s “further 10 years of environmental tobacco smoke exposure is a ‘strand in the cable’”. Further, given the occurrence of lung cancer, this led him to infer that environmental tobacco smoking exposure substantially contributed to the contraction of the worker’s lung cancer and that it was real and of substance, even if the comparative contribution of cigarette smoking was greater in dosage [110]. 12. The reference to a “strand in the cable” was, presumably, a reference to the statement by Spigelman CJ in Seltsam Pty Ltd v McGuiness [2000] NSWCA 29 that “[c]ausation, like any other fact can be established by a process of inference which combines primary facts like ‘strands in a cable’ rather than ‘links in a chain’, to use Wigmore’s 5 simile. (Wigmore on Evidence (3rd ed) para 2497, referred to in Shepherd v R [1990] HCA 56; (1990) 170 CLR 573 at 579)”. However, the Arbitrator’s statement came after he said he had particular regard to a submission (and evidence) that supported a contrary conclusion [111]–[112]. 13 There may be many “strands in the cable” that justified a positive conclusion on the causation issue in this case. However, the Arbitrator referred to none of them [113]. 14. The decision could not stand, however, that did not mean there should have been an award for the appellant. The summary of the evidence demonstrated that there was evidence, which, when properly considered, may support a conclusion in favour of the worker. The parties did not apply to have the matter re-determined by the Deputy President. As a result, the matter was remitted to a different Arbitrator for redetermination [114]. 15. Since the matter was to be re-determined in any event, it was not strictly necessary to determine the third ground of appeal, which related to the Arbitrator’s failure to determine whether the disease of lung cancer is a disease of gradual onset [115]. 16. The appeal succeeded on the ground that the Arbitrator failed to give any adequate reasons for his decision, and failed to properly consider the evidence and issues in dispute. However, many of the appellant’s submissions were without merit and were made without any regard to the evidence or the authorities [124]. 6 McGowan v Secretary, Department of Education and Communities [2014] NSWWCCPD 51 Boilermaker’s deafness; claim for lump sum compensation for binaural hearing loss; dispute as to the nature and extent of the hearing loss; role of Commission and AMSs in such a dispute; consequence of finding that employment was employment to the nature of which the injury of boilermaker’s deafness was due; terms of referral to AMS; effect of invalid MAC; need for further medical assessment; s 17 of the 1987 Act; ss 293, 319, 321, 326 and 329 of the 1998 Act; whether orders made were interlocutory or final; extension of time to appeal; Pt 16 r 16.2(12) of the 2011 Rules Roche DP 6 August 2014 Facts: The appellant worker, James McGowan, worked for the respondent employer from 1994 as a technical assistant/storeman at two of the respondent’s TAFE training workshops. The work exposed him to workshop noise from grinding, power drills, hammering, a guillotine for tinplate, and a bending machine. On 8 June 2012, the deemed date of injury, the worker claimed lump sum compensation of $8,250 in respect of 12.1 per cent binaural hearing loss (which equated to six per cent whole person impairment) plus the cost of hearing aids. The basis of the claim was that his employment was employment to the nature of which his injury was due. The injury was alleged to be a loss of hearing of such a nature as to be caused by a gradual process, that is, boilermaker’s deafness or deafness of a similar origin (s 17(1) and (2) of the 1987 Act). As the worker made his claim before 19 June 2012, the claim for lump sum compensation was not caught by the amendments introduced by the Workers Compensation Legislation Amendment Act 2012 (cl 15 of Pt 19H of Sch 6 to the 1987 Act). As a result, s 69A applied. That section provided that in assessing a claim for permanent impairment compensation as a result of loss of hearing due to boilermaker’s deafness, regard must not be had to any hearing loss due to boilermaker’s deafness unless the worker’s total hearing loss due to boilermaker’s deafness is at least six per cent (s 69A(1)). In determining the percentage of loss of hearing due to boilermaker’s deafness, that loss of hearing is to be determined as a proportionate loss of hearing of both ears, even if the loss is in one ear only (s 69A(5)). On 30 August 2012, the respondent’s insurer, Allianz Australia Insurance Ltd, disputed liability. In an extempore decision delivered on 19 December 2013, the Arbitrator accepted the worker’s evidence that his work with the respondent exposed him, on average, to noise from drilling, grinding and hammering for three-and-a half hours per day. Consistent with Blayney Shire Council v Lobley (1995) 12 NSWCCR 52, the Arbitrator found that the tendencies, incidents and characteristics of the worker’s employment with the respondent could give rise to a risk of industrial deafness. Thus, the Arbitrator found that Mr McGowan’s employment with the respondent was employment to the nature of which boilermaker’s deafness was due. This finding was not challenged. The Arbitrator added that it was only noise exposure in respect of the left ear that was sufficient to satisfy the requirement of the authorities that the characteristics of the worker’s 7 employment were of a type as to give rise to a real risk of boilermaker’s deafness. As a result, the Arbitrator made an award for the respondent in respect of the right ear. As required by s 293(2) of the 1998 Act, the Arbitrator remitted the assessment of the degree of whole person impairment in respect of any industrial deafness in the worker’s left ear to the Registrar for referral to an AMS. He ordered the respondent reimburse the worker for the cost of a hearing aid for the left ear and ordered an award for the Respondent in respect of the right ear. The AMS, Dr Harrison, noted that the usual method of assessment would be to apportion the industrial deafness affecting the right ear to the same amount of industrial deafness affecting the left and so determine the binaural hearing impairment. However, he noted that this would have been contrary to how he was instructed to make the assessment which was to assess the industrial deafness affecting the left ear only. In compliance with the Arbitrator’s direction, Dr Harrison assessed Mr McGowan’s binaural hearing loss on the assumption that, contrary to the fact, the hearing loss affecting the right ear, at every frequency, was nil. That gave a binaural hearing loss of 4.2 per cent. After a deduction for presbycusis, because of Mr McGowan’s age, that gave a binaural hearing loss of 2.2 per cent, which equalled nil per cent whole person impairment. In an appeal filed on 17 April 2014, Mr McGowan challenged the determination of 26 March 2014 and the orders made on 23 December 2013. The issues in dispute in the appeal were whether the Arbitrator erred in: (a) entering an award for the respondent in respect of the right ear, and (b) referring only the left ear for assessment by the AMS. Held: The appeal was allowed. The applicant worker’s employment with the respondent employer was employment to the nature of which the injury of boilermaker’s deafness is due. The assessment of the applicant worker’s binaural hearing loss, and the need for hearing aids, was referred to Dr Harrison for a further assessment under s 329(1)(b) of the 1998 Act. Discussion and findings 1. On the evidence available to the Arbitrator in December 2013, it was not open to him to find that the tendencies and incidents of the relevant employment were liable to cause boilermaker’s deafness in one ear but not the other. Such a finding suggested that one ear was exposed to loud noise in the course of employment but the other was not. If the employment were employment to the nature of which the injury is due, unless there was an unusual feature that made the noise affect only one ear, which is improbable, then, as the AMS noted, it would have affected hearing in both ears [61]. 2. By making a finding that Mr McGowan did not suffer an injury to his right ear the Arbitrator was purporting to make a finding on the actual cause of the loss of hearing in that ear. That is not something that is required by s 17 and, in a claim for lump sum compensation for hearing loss, is not permitted unless an AMS has first assessed the nature and extent of the loss of hearing, in which case the AMS’s assessment, in a valid MAC, is conclusively presumed to be correct (s 326(1)(c)). At the date of the first orders, made on 23 December 2013, there had been no assessment by an AMS. Thus, the Arbitrator erred in purporting to make an award for the respondent in respect of Mr McGowan’s right ear and in the terms of the referral to the AMS [62]. 8 3. An Arbitrator cannot resolve the nature and extent of the hearing loss. That is because the legislature has reserved that question for an AMS. Thus, where the injury is the loss, or further loss, of hearing contracted by a gradual process, the dispute, if any, as to the nature and extent of the injury is determined not by the Commission but by an AMS. This is the reverse of the usual situation. Normally, the nature and extent of a worker’s injury, that is, whether a worker has received an injury, is a liability issue that is determined by the Commission before the matter is referred to an AMS for assessment of the degree of whole person impairment that has resulted from that injury (Connor v Trustees of the Roman Catholic Church for the Archdiocese of Sydney [2006] NSWWCCPD 124; 5 DDCR 337; s 321(4)(a)) [69]. 4. In a claim for lump sum compensation for hearing loss, s 321(4)(a) must be read, in context, to mean “[t]he Registrar may not refer for assessment under this Part a medical dispute concerning permanent impairment (including hearing loss) of an injured worker where liability is in issue and has not been determined by the Commission, save for a claim for lump sum compensation for hearing loss where ss 319(e) and 326(1)(c) apply” (emphasis added) [72]. 5. This interpretation applied the words of the legislation (Alcan (NT) Alumina Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Territory Revenue [2009] HCA 41; [2009] HCA 41; 239 CLR 27) in a way that best gives effect to “the purpose and language of those provisions while maintaining the unity of all the statutory provisions” (Project Blue Sky Inc v Australian Broadcasting Authority [1998] HCA 28; 194 CLR 355 (Project Blue Sky)). It was not a matter of adding words to the legislation, but a matter of the construction of the words the legislature has enacted (Taylor v The Owners – Strata Plan No 11564 [2014] HCA 9) so as to best give effect to the intention of Parliament [73]. 6. Consistent with Project Blue Sky, this treated sub-s (2) of s 293, as the “leading provision” and sub-ss (4)(a) of s 321 and (3) of s 293 as the “subordinate provision[s]”. Given the use of the mandatory “must” in s 293(2), as against the permissive “may” in the other subsections, which is appropriate in the circumstances of a claim for lump sum compensation for hearing loss [74]. 7. The effect of this interpretation was sensible and workable. The Commission, which is best equipped to hear and determine disputes about the level of noise to which a worker is exposed, which will often involve the weighing of conflicting lay and expert evidence, determines whether the employment was employment to the nature of which the injury was due [75]. 8. AMSs, who are, because of their training and expertise, best equipped to determine medical disputes, determine the nature and extent of the loss of hearing, including any deduction for a pre-existing condition or abnormality, such as, for example, the acoustic neuroma in Mr McGowan’s right ear [76]. 9. The end result in the present case was that, by making an award for the respondent in respect of the right ear, the Arbitrator determined the “nature and extent of the loss of hearing” suffered by the worker in his right ear to be nil, when he had no power to do so. The issue before him was whether the worker’s employment with the respondent was employment to the nature of which the injury was due. The Arbitrator determined that question in favour of the worker and the next step in the process was for the nature and extent of hearing loss to be assessed by an AMS [77]. 10. This raised a further complication. While a MAC is conclusively presumed to be correct, a determination made in reliance upon an invalid or defective MAC is invalid 9 (Jopa Pty Ltd t/as Tricia’s Clip-n-Snip v Edenden [2004] NSWWCCPD 50 and Ryan v State Transit Authority of NSW [2004] NSWWCCPD 81) [78]. 11. In the present case, Dr Harrison’s MAC was based on a fundamentally flawed referral. That was because, as directed, he only assessed Mr McGowan’s hearing loss in his left ear when the claim, which was properly supported by appropriate medical evidence, was for loss of hearing in both ears and where the Commission had determined that Mr McGowan’s employment was employment to the nature of which the injury of boilermaker’s deafness was due. Though the doctor was well aware of the error, he felt bound to follow the Arbitrator’s incorrect direction, which he did. However, the Commission is bound to act according to law and a Certificate of Determination based on an invalid MAC is invalid and cannot stand [81]. 12. This follows notwithstanding that Mr McGowan did not appeal against the MAC under s 327 of the 1998 Act. The only grounds of appeal that might have been available under that section were that the MAC contained a demonstrable error, or was made on the basis of incorrect criteria. The difficulty with such arguments is that the AMS followed the directions of the Arbitrator. Thus, the error was by the Arbitrator and there was no demonstrable error by the AMS. Moreover, there is no evidence that the MAC was made on the basis of incorrect criteria [82]. 10 StateCover Mutual Ltd v Cameron [2014] NSWWCCPD 49 Claim for lump sum death benefit; disease contracted by a gradual process; melanoma; whether Arbitrator erred in relying on hearsay evidence; Commission not bound by the rules of evidence; Pt 15 r 15.2 of the 2011 Rules; whether employment a substantial contributing factor to the contraction of the disease; interpretation of special insurance provisions relating to occupational diseases; ss 4(b)(i), 15(1)(b) and 18(1) of the 1987 Act; relevance of s 151AB of the 1987 Act in a claim for workers’ compensation benefits Roche DP 4 August 2014 Facts: Rebecca Cameron, the respondent on appeal, was the eldest daughter of Alan Steere (the deceased) who died on 19 July 2011 from metastatic melanoma. She claimed the lump sum death benefit as the deceased’s legal personal representative. Ms Cameron’s case was that her father’s duties with Greater Taree City Council (the Council) (and its predecessor, Manning Shire Council) between 1974 and 1984 and, to a lesser extent, between 1984 and 1986, exposed him to sunlight and that the exposure was a substantial contributing factor to the contraction by him of the disease of melanoma, which was first diagnosed on his left cheek in September 2003. The deceased underwent various operations for his condition, but the melanoma metastasised to the brain in July 2008 and, after more surgery in 2008 and 2009, he died from the melanoma on 19 July 2011. The council employed the deceased between 6 May 1974 and 25 February 2011 (he stopped working on 20 June 2008). From 1983 until 2011, the Council had three insurers: (a) from 31 December 1983 to 31 December 1986 – AAI Ltd t/as GIO (the second respondent on appeal) (GIO); (b) from 1 July 1987 to 31 December 2001 – GIO General Ltd, and (c) from 31 December 2001 to 31 December 2014 – StateCover Mutual Ltd (StateCover) (the appellant). Though GIO General Ltd participated in the arbitration, it was not joined to the appeal. Consistent with StateCover Mutual Ltd v Smith [2012] NSWCA 27, the insurers, save for GIO General Ltd, were joined as separate parties under Pt 11 r 1(4)(b) of the 2011 Rules. Though not separate parties before the Arbitrator, they were separately represented and acted as if they were separate parties. The Application alleged a date of injury of 19 July 2011, that is, the date of death. It alleged the cause of death to be “due to excessive exposure to sunlight” during the deceased’s employment with the Council. At the arbitration, the period of employment relied on as being causally related to the development of the melanoma was from 1974 to 1986 as it was accepted the deceased worked indoors from 1986 until stopping work in 2008. The claim was based on the disease provisions in s 4(b)(i) of the 1987 Act. At the time applicable to this claim, that provision provided that an injury includes “a disease which is contracted by a worker in the course of employment and to which the employment was a contributing factor”. 11 After referring to the extensive lay and expert evidence dealing with the deceased’s exposure to sunlight, the Arbitrator concluded that the deceased suffered a disease injury in the form of metastatic melanoma, which he contracted in the course of his employment with the Council and to which his employment was a substantial contributing factor. He also found that, as the disease was of such a nature to be contracted by a gradual process, s 15 applied and the deemed date of injury was the date of death, 19 July 2011 (s 15(1)(a)(i)). Applying s 18 of the 1987 Act, the Arbitrator held that the liability of the Council was taken to have arisen immediately before the deceased ceased to be employed by the employer. Therefore, StateCover was liable under its policy in respect of the compensation for which the Council was liable under s 15. The issues in dispute on the appeal were whether the Arbitrator erred in: (a) relying on hearsay evidence (hearsay evidence); (b) finding that the deceased’s employment was a substantial contributing factor to the injury (substantial contributing factor), and (c) failing to find that StateCover was the insurer liable for the deceased’s injury (the relevant insurer). Held: The Arbitrator’s determination was confirmed. Hearsay Evidence 1. The evidence objected to on appeal had been admitted without objection at the Arbitration. Parties are bound by the conduct of their case at arbitration (University of Wollongong v Metwally (No 2) (1985) 59 ALJR 481) [29]. 2. StateCover objected to an unauthored document that had previously been admitted without objection at arbitration. The relevance of the unauthored document, which provided commentary on the deceased’s working life, was unclear. Although the Arbitrator referred to it when summarising Ms Cameron’s submissions, he made no further reference to it and it did not seem to play any role in his determination. The Arbitrator based his decision on the extensive evidence in several other documents and therefore, the unauthored document was largely irrelevant [30]. 3. The Arbitrator did not wholly base his conclusion on the hearsay evidence from Ms Cameron and Ms Murray, the deceased’s former wife. He based it on the clear, unchallenged, evidence from witnesses who worked with the deceased. Each gave a consistent account of the deceased’s exposure to sunlight for the overwhelming majority of his working hours. Even without the hearsay evidence from Ms Cameron and Ms Murray, the Arbitrator’s conclusion was open and disclosed no error [40]. 4. The hearsay evidence was not procedurally unfair. The evidence from the co-workers was not hearsay and was not challenged. It was open to the Arbitrator to note that the Council tendered no evidence to contradict the evidence of the level of sunlight to which the deceased was exposed between 1974 and 1986. There was no procedural unfairness in the Arbitrator’s approach [41]. 5. The evidence on which the Arbitrator based his ultimate finding with regard to the level of sunlight to which the deceased was exposed between 1974 and 1986 was mainly direct evidence from Ms Murray and from the deceased’s co-workers, Messrs Sadler, Emerton and Connell. That evidence was unchallenged. To the extent that the Arbitrator relied on hearsay evidence from Ms Murray, the evidence was relevant, 12 logical, and probative and, as the Commission is not bound by the rules of evidence, the Arbitrator was entitled to rely on it [45]. 6. Based on the Arbitrator’s findings, especially the evidence of the deceased’s coworkers, it was open to the Arbitrator to conclude that the history of Professor McCarthy, Fellow of the Australian College of Surgeons, qualified for StateCover, was not accurate. The Arbitrator’s findings were based on an assessment of the whole of the lay evidence, noting that the Council called no evidence. That approach was open and disclosed no error [50]. Substantial contributing factor 7. Having regard to the whole of the evidence, the Arbitrator concluded that the deceased’s employment was a substantial contributing factor to the development of the disease [68]. 8. The Arbitrator’s specific findings under s 9A(2) were not challenged and each was open on, and consistent with, the evidence [69]. 9. Assessment of whether employment is a substantial contributing factor to an injury is not purely a medical question (Awder Pty Ltd t/as Peninsular Nursing Home v Kernick [2006] NSWWCCPD 222). As with the test for determining whether a legal incapacity exists (in the context of the Limitation Act 1969), it was for the arbitrator to decide, on the basis of the totality of all the evidence, both lay and expert, whether the relevant test has been satisfied (Guthrie v Spence [2009] NSWCA 369) [70]. 10. Moreover, a finding that employment is a substantial contributing factor to the injury within s 9A is a finding of fact (Department of Education and Training v Sinclair [2005] NSWCA 465) [71]. 11. The Arbitrator not only took a realistic view of the evidence, his conclusion was consistent with it and disclosed no error [72]. The relevant insurer 12. Consistent with GIO Workers Compensation (NSW) Ltd v GIO General Ltd (1995) 12 NSWCCR 187 (GIO v GIO), the Arbitrator found that the deemed date of injury was 19 July 2011, the date of death. That finding was not challenged. The Arbitrator correctly noted that, under s 15(1)(b) of the 1987 Act, compensation is “payable by the employer who last employed the worker in employment to the nature of which the disease was due” (emphasis added) [83]. 13. The Arbitrator then considered s 18(1), which applies to claims for workers compensation involving occupational diseases and applied in the present matter. Applying s 18(1), he determined the date of injury of 19 July 2011 was after the deceased ceased to be employed by the respondent on 25 February 2011. Therefore the liability of the employer was taken to have arisen immediately before that date, when insured by StateCover [84]. 14. As the liability of the employer (in this case, the Council) arose immediately before the deceased ceased to be employed by it (in this case, on 25 February 2011), the insurer on risk at that time (in this case, StateCover) was liable to indemnify the employer. The result, which flowed from the unambiguous language of relevant legislation, was clear [87]. 13 15. Section 151AB, which applies to claims for common law damages, does not apply to claims for workers compensation [103]. 16. The authority on which StateCover relied, CIC Workers Compensation (NSW) Ltd v Alcan Australia Ltd (1994) 35 NSWLR 169 concerned s 151AB and had no application in the present case [90]. 14 Northern NSW Local Health District (Tweed Heads Hospital) v Conaghan [2014] NSWWCCPD 54 Section 4 the 1987 Act Act; injury arising out of or in course of employment; worker injured as a result of altercation with fellow worker and its consequences; challenge to finding that injury arose out of employment; consideration of decisions in Tarry v Warringah Shire Council [1974] WCR (NSW) 1 and Davis v Mobil Oil Australia Ltd (1988) 12 NSWLR 10 O’Grady DP 28 August 2014 Facts: Mr Conaghan allegedly received psychological injury arising out of or in the course of his employment as a wardsman at the appellant’s hospital premises at Tweed Heads, New South Wales. On 1 March 2011, Mr Congahan and a fellow employee, Ms Bernadette McCullough, became involved in an altercation. Mr Conaghan was arrested by the police on 12 May 2011 and charged with the offence of common assault. Mr Conaghan entered a plea of guilty to that charge. The presiding Magistrate found Mr Conaghan guilty of the offence but, without proceeding to conviction, directed that he enter into a good behaviour bond for six months pursuant to s 10(1)(b) of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999. The worker’s case before the Arbitrator was that between the date of the altercation and 4 May 2011, he was the subject of discriminatory and harassing treatment by other staff. This included verbal abuse, constant telephone calls and other conduct which caused the alleged injury. The worker ceased work on 4 May 2011 due to the alleged injury and made a claim for compensation. On 27 May 2011, Mr Conaghan received written notice, pursuant to s 74 of 1998 Act, from the appellant’s insurer that his claim for compensation had been declined. On 17 August 2012, the worker’s solicitors made a claim against the appellant in respect of weekly compensation, medical expenses and lump sum compensation pursuant to ss 66 and 67 of the 1987 Act. On 4 September 2012, the appellant’s insurer again gave the worker notice pursuant to s 74 of the 1998 Act, that his claim in respect of compensation benefits had been declined. That notice included a denial of injury and a statement that, in reaching its decision, reliance was placed by the appellant upon the provisions of ss 9A and s 11A of the 1987 Act. Mr Conaghan filed an Application to Resolve a Dispute with the Commission in December 2012. The day before the matter was listed for hearing before an Arbitrator, the appellant applied to admit a statement of Ms McCullough into evidence. Ms McCullough’s statement had been recorded that same day. The statement described the altercation, which was substantially similar to the worker’s description as found in evidence. The statement provided particular details concerning Mr Conaghan’s physical conduct: Ms McCullough asserted that Mr Conaghan obstructed her passage and confined her against a wall when he verbally abused her. The statement included allegations that Mr Conaghan “grabbed” Ms McCullough and shook her and also alleged that Mr Conaghan grabbed Ms McCullough by the right arm and pushed her arm into her stomach and began to shake her uncontrollably. Counsel for the appellant at the hearing indicated from the bar table that Ms McCullough had been reluctant 15 to provide a statement because she “also has a claim for compensation” arising out of the subject altercation. The Arbitrator acknowledged that, had the evidence been admitted, the matter would have had to be adjourned to avoid any prejudice to Mr Conaghan. On balance the Arbitrator concluded that there was no real foundation on which to exercise the discretion in favour of the appellant. Tender of the statement was refused. The appellant then sought an adjournment of the proceedings, which application was refused by the Arbitrator. No complaint is made on this appeal concerning that refusal. A Certificate of Determination was issued by the Commission on 12 May 2014, accompanied by a Statement of the Arbitrator’s Reasons. The Arbitrator found that the worker suffered psychological injury arising out of the period of his employment from 1 March 2011 to 4 May 2011 for the purposes of section 4(b)(i) of the 1987 Act with a deemed date of injury of 4 May 2011. The applicant’s employment was a substantial contributing factor to that injury as required by section 9A. The appellant challenged the Arbitrator’s finding. The issues in dispute on appeal were whether the Arbitrator erred in: (a) excluding the evidence of Ms McCullough (Ground one); and (b) determining that the worker’s injury arose out of his employment in the terms of s 4 of the 1987 Act (Ground two). Held: The Arbitrator’s findings and orders were confirmed. Ground one 1. The manner in which proceedings are conducted before the Commission is regulated by the 2011 Rules. The lodgment of evidentiary material with the Commission in the course of proceedings is regulated by Pt 10 of the 2011 Rules [54]. 2. The appellant correctly characterised the Arbitrator’s ruling concerning the exclusion of Ms McCullough’s evidence as being an interlocutory ruling. In reaching her decision concerning the appellant’s application to tender that evidence, the Arbitrator plainly exercised her discretion. Ward JA in Cicek v The Estate of the Late Mark Solomon [2014] NSWCA 278 at [70] noted: “What is required is that the appellants establish an error of legal principle; material error of fact; that the primary judge took into account some irrelevant consideration or failed to take into account or give sufficient weight to a relevant consideration; or that the primary judge arrived at a result so unreasonable or unjust as to suggest such an error (House v R [1936] HCA 40; (1936) 55 CLR 499 at 505; Micallef per Heydon JA, as his Honour then was, at [45]). In Kelly v Mina [2014] NSWCA 9 at [46], it was recognised that an appellate court should be slow to interfere and ought not to reverse the primary judge's decision on a matter of practice and procedure unless convinced it is plainly erroneous.” [55] 3. The thrust of the appellant’s argument on appeal suggested the exclusion of Ms McCullough’s evidence gave rise to significant prejudice. It was asserted that such prejudice arose by reason of the absence of Ms McCullough’s “side of the story” concerning the subject altercation. It was the appellant’s argument that Mr Conaghan’s conduct had taken him “outside his employment”, given that his conduct constituted assault. The fact of the assault was plainly established on Mr Conaghan’s case. The 16 appellant did not make out a persuasive argument that error occurred with respect to its application to adduce the evidence of Ms McCullough [56]. Ground two 4. The appellant argued before the Arbitrator that, assuming that psychological injury had been received by the worker, such injury was occasioned by reason of the assault and the consequences, being police intervention, the charge and subsequent court appearance when a guilty plea was entered. It was argued that the worker’s conduct during the altercation took him outside the course of his employment, and that the police intervention and arrest were not causally related to his employment. These arguments were reiterated on appeal [59]. 5. On appeal the appellant, for the first time, included reference to the term “gross misconduct” (Hatzimanolis v ANI Corporation Limited [1992] HCA 21; 173 CLR 473 (Hatzimanolis)). A difficulty arose on appeal as the argument failed to distinguish between matters directed to the question whether the alleged injury arose in the course of employment, or to whether it arose out of the employment. Notwithstanding the blurring of this distinction, it was argued that the worker’s conduct took him outside his employment and that the police intervention, the subsequent arrest and charge of assault, whilst causative of injury, did not arise out of the employment [60]–[61]. 6. The concept of “gross misconduct” as discussed in Hatzimanolis is included in the statutory concept of serious and wilful misconduct as it appears in s 14(2) (Higgins v Galibal Pty Ltd t/as Hotel Nikko Darling Harbour (1998) 45 NSWLR 45) [63]. 7. The legislation provided that, upon proof of the commission of serious and wilful misconduct, and subject to the proviso in s 14(2) concerning death or serious and permanent disablement, an injured worker who is guilty of such conduct is disentitled to receipt of compensation benefits. That disentitlement may embrace a situation where gross misconduct as discussed in Hatzimanolis is made out. However, no argument was advanced concerning any possible relevance of the provision [64]. 8. The difficulty with the appellant’s argument as advanced was that the Arbitrator had made a finding that there was an “unbroken causal connection” between the altercation and its consequences, including the police intervention, and the injury [65]. 9. As was the case in Tarry v Warringah Shire Council [1974] WCR (NSW) 1, the events which gave rise to the altercation and its consequences were, as found by the Arbitrator, all related to employment. In such circumstances a resultant injury arose, as a matter of law, out of the employment: Davis v Mobil Oil Australia Ltd (1988) 12 NSWLR 10. The appellant failed to make any convincing argument concerning the Arbitrator’s findings of fact, or that her ultimate conclusion was reached in error [68]. 17 O v Nepean Blue Mountains Local Health District [2014] NSWWCCPD 52 Challenge to factual findings; assessment of expert evidence; application of the principles in Paric v John Holland (Constructions) Pty Ltd [1985] HCA 58; 62 ALR 85; 59 ALJR 844 Keating P 13 August 2014 Facts: The worker was employed by Nepean Blue Mountains Local Health District (NBMLHD) as a rehabilitation co-ordinator. He alleged that as a result of recurrent “harassment and victimisation” in the course of his employment he suffered a post-traumatic stress syndrome, depression and psychological injury. In particular, the worker alleged that his work performance was measured against a Performance Improvement Plan (PIP) for an excessively long period. The worker was initially employed by Sydney West Area Health Service (SWAHS) until it split into two local health districts, one being NBMLHD. Following his return to work at SWAHS after unrelated surgery in June 2011, the worker was placed on a PIP. In October 2011, the worker was transferred to NBMLHD. The worker alleged that following the transfer the PIP remained in place for the duration of his employment with NBMLHD. The worker claimed weekly compensation from 16 August 2012, being his last day of work with NBMLHD. That claim was denied by the employer’s insurer. The matter came before the Commission and an Arbitrator found in favour of the employer, on the basis that the worker failed to discharge the onus of establishing that he suffered an injury within the meaning of s 4(b)(i) of the 1987 Act. The worker appealed. The issues in dispute on appeal were whether the Arbitrator erred by: (a) rejecting the worker’s medical case (being the opinions of Dr Megaly, general practitioner, and Dr Robert Hampshire, consultant psychiatrist) by incorrectly reasoning that the assumed facts by which those medical opinions were premised, were not supported by the evidence when there was such supportive evidence before her, and (b) failing to properly consider all the evidence by confining her reasons, and thus her fact finding enquiry as to the main cause of the worker’s alleged psychiatric work injury, to the allegation of an enduring PIP when there were additional and compound work related causes for the onset of his condition. Those other causes relate to allegations of an excessive workload and the absence of a clear delineation of his role and duties. At a telephone conference before the President the following issues were conceded: (a) the case before the Arbitrator was argued as a disease injury under s 4(b)(i) and not as an aggravation of a disease under s 4(b)(ii); (b) that the worker suffers from a psychological condition; 18 (c) the case was not argued on the basis that the worker’s injury arose from a perception of events in the course of his employment, and (d) that where injury pursuant to s 4(b)(i) is alleged and where the deemed date of injury is after 19 June 2012, as it was in this case, s 9A of the 1987 Act is not relevant. Held: The Arbitrator’s determination was confirmed. Discussion and Findings 1. The worker was placed on a PIP in June 2011 in response to issues concerning his interaction and behaviour with his colleagues and an inability to time manage. There was no dispute that the worker’s performance against the PIP was subject to formal evaluations on 9 August 2011, 6 September 2011 and 24 October 2011 [110]. 2. Although the worker told his doctors that he was subject to a PIP for the duration of his employment, the objective evidence did not support that assertion. It was clear that there was an intention to develop a new plan relevant to the worker’s current employment and job requirements [112]–[113]. 3. The evidence of one of the worker’s supervisors at NBMLHD, Ms Fedeli, (which was not challenged, which was confirmed by various email exchanges that were in evidence and which the Arbitrator accepted) in particular, supported the conclusion that it may have been intended that the SWAHS PIP would continue to apply to the worker after his transfer to NBMLHD in October 2011. However, by February 2012 it was recognised that only two of the areas requiring performance improvement on that plan were relevant to the worker’s employment at NBMLHD. That was communicated to the worker by Ms Fedeli in February 2012 and thereafter attempts were made to develop a plan that was relevant to his employment at NBMLHD [111], [117]. 4. It followed that the conclusion reached by the Arbitrator that the worker had not discharged the onus of proving that the PIP remained on foot for the duration of his employment, was correct and did not involve error [119]. 5. It is now well accepted that the facts assumed by an expert do not have to correspond “with complete precision” with the facts established. However, the facts upon which the expert relies must be “sufficiently like” the facts established to “render the opinion of the expert of any value”: Paric v John Holland (Constructions) Pty Ltd [1985] HCA 58; 62 ALR 85; 59 ALJR 844 [122]. 6. The fundamental premise underlying the opinions of Dr Hampshire and Dr Megaly was that the worker was held to the PIP from early-mid 2011 until he ceased work in August 2012. That fact had not been established and was contrary to the accepted evidence. For that reason, the Arbitrator was correct to find that the doctors’ opinions did not carry any great weight [123]–[124]. 7. The worker’s second ground of appeal alleged that the Arbitrator erred by failing to consider evidence of abuse and wrong dealing by officers of the respondent as contained in his chronology of events [126]. 8. The Arbitrator acknowledged the worker’s allegation of overwork and bullying by his supervisors, although she quite rightly identified that the focus of his complaint was on the maintenance of an unreasonable PIP, rather than bullying more generally. The Arbitrator also acknowledged evidence of complaint to his sister that he felt very 19 distressed and preoccupied by his work, together with the general practitioner’s notes and hospital admission notes referring to complaints of workplace bullying and harassment [127]–[128]. 9. Aside from making these general complaints, the evidence of workplace bullying or harassment, or indeed overwork, was scant. The appellant’s submissions referred in general terms to the worker’s chronology, but failed to identify any particular episode or episodes in support of his submissions [130]. 10. The Arbitrator made no finding concerning the worker’s workload as a contributing factor to the contraction of his disease. That was not surprising as she was not invited to do so. Even if it was accepted that the worker worked excessive hours for a period in 2010, that ceased in November 2010, which was almost two years before the deemed date of injury. There was no evidence to support a finding of excessive working hours after 2010, nor was there any expert evidence of a causal connection between working excessive hours and the onset of the worker’s condition. Therefore, if the Arbitrator erred in not dealing with this issue, it made no difference to the outcome [133]. 11. The Arbitrator noted the worker’s allegations of recurring harassment and victimisation as a causative factor leading to his condition. However, no evidence was led that the worker was harassed or victimised (other than through the PIP). Moreover, no relevant submissions were made to the Arbitrator which supported a finding that harassment and victimisation caused the worker’s condition, much less, were the main contributing factor to its contraction. In these circumstances, the Arbitrator was not required to deal with the issue in any more detail than she did [134]. 12. The Arbitrator’s finding that she was not satisfied that the worker discharged the onus of establishing that he suffered an injury within the meaning of s 4 of the 1987 Act was open and did not involve error [136]. 20 Transgrid v Pryor [2014] NSWWCCPD 50 Injury; challenge to factual findings; inadequacy of reasons for decision O’Grady DP 6 August 2014 Facts: Mr Pryor alleged that he received injury in the course of his employment with Transgrid (the appellant) on 22 and 24 February 2006. On 22 February 2006 Mr Pryor was moving heavy gas bottles from a welding trolley. It was Mr Pryor’s allegation that, during this activity, he felt pain in his neck, his right shoulder and right arm. On 24 February 2006 further injury allegedly occurred as he attempted to move a trolley. Mr Pryor, by reason of favouring his right shoulder and arm, also alleged that he has suffered a consequential condition in his left shoulder. A claim made on behalf of Mr Pryor in respect of lump sum compensation was declined by the appellant. Notice of the rejection of that claim, and the reasons for that decision, was given to Mr Pryor’s solicitors by letter dated 26 April 2013 as is required by s 74 of the 1998 Act. The dispute between the parties came before the Commission for Arbitration on 17 February 2014. Mr Pryor made an application seeking an award in respect of lump sum compensation pursuant to s 66 and s 67 of the 1987 Act. The matter proceeded to hearing and the Arbitrator delivered his determination of the dispute extempore on that day. The Arbitrator made a finding with respect to the dispute as to injury, “that both [Mr Pryor’s] cervical, left and right shoulder injuries arose out of the work incidents [sic] of 22 February 2006. That is, he suffered injury to those body parts on those occasions and that his employment with the Respondent was a substantial contributing factor to those injuries and conditions”. The employer appealed. The issues in dispute in the appeal concerned questions as to whether the Arbitrator erred in the following respects: (a) failing to state sufficient reasons for his determinations of fact concerning the receipt by Mr Pryor of the injuries alleged; (b) admitting into evidence the report of Dr Brian J Noll, orthopaedic surgeon, dated 19 March 2009, in contravention of cl 49 of Pt 9 of the 2010 Regulation; (c) failing to address the evidence of the expert medical witnesses, in particular those opinions expressed by those witnesses that were conflicting, when determining questions of fact; (d) in determining that Mr Pryor had received an injury to his left shoulder, and (e) determining the dispute upon a basis not argued at the hearing, giving rise to a denial of procedural fairness. Held: The findings and orders of the Arbitrator were revoked. The matter was remitted for hearing afresh to another Arbitrator. 21 Disposition of the appeal 1. The appellant’s first complaint, ground (a), was that the Arbitrator failed to provide adequate reasons for his decision. There is an obligation upon an Arbitrator to provide such reasons. Failure to meet that obligation constitutes error of law. This ground was closely associated with ground (c) which asserted error “in the consideration and assessment of the evidence in determining disputed issues”. The appellant’s complaint required examination of the Arbitrator’s Reasons to determine whether those matters stated by him sufficiently demonstrated his reasoning and, more particularly, whether he “engaged with” or entered into the contested issues as was required [56]–[57]. 2. It was the appellant’s argument before the Arbitrator that there had been no injury of significance to Mr Pryor’s right shoulder in February 2006; that a 2008 non-work injury plainly involved a significant shoulder injury, and that investigations were first conducted after that latter injury which disclosed the significant tear. The point was also made that medical treatment rendered immediately following the 2006 incident was founded upon a diagnosis, not concerning the shoulder, but concerning the cervical spine injury [58]. 3. The facts of the matter were complex. The manner in which the evidence had been presented, including the tender of evidence of Dr Bodel, qualified by the worker’s solicitors, which was accepted by the Arbitrator as containing a probable error, compounded this complexity. The submissions put by the appellant required a careful analysis of the evidence as a whole to enable a proper assessment of the validity of the appellant’s argument. Such approach was not adopted by the Arbitrator. Rather there was a cursory reference to the notations found in the clinical notes of Dr Allen, the worker’s general practitioner. The Arbitrator’s conclusion concerning the occurrence of the right shoulder injury in 2006 appeared to be founded upon the brief notations of “niggling” in the shoulder without there being any meaningful “engagement” with the issues raised by the appellant, as discussed by Santow JA in Haris v Bulldogs Rugby League Club [2006] NSWCA 53 [59]. 4. The Arbitrator, later in his Reasons, returned to the subject of the disputed right shoulder injury and made reference to the opinion of Dr Sharp, orthopaedic surgeon. Dr Sharp’s opinion, making reference to “an injury some years ago that started all this off”, supported an argument that, as at 2008, Mr Pryor carried an “old” injury to his shoulder, being the tear diagnosed. The question remained as to whether contemporary evidence was such that a conclusion of relevant injury in 2006 could properly be reached.The Arbitrator’s reliance upon Dr Sharp’s opinion, stated after reaching his factual finding concerning the right shoulder injury, did not constitute a sufficient reason, or basis, for his ultimate conclusion that relevant injury was received in 2006. The Arbitrator’s apparent acceptance of the evidence of Dr Bodel concerning the occurrence of alleged injury to the cervical spine, and his rejection of the evidence of Dr Smith, was not attended by sufficient reasons as required [60]–[61]. 5. The Arbitrator did not provide sufficient reasons for his apparent acceptance of the evidence of Dr Bodel concerning the occurrence of alleged injury to the cervical spine, and his rejection of Dr Smith’s evidence. The Deputy President formed that view given the Arbitrator’s acceptance of the deficiency found in the history as recorded by Dr Bodel and the absence of any evaluation by him of either the weight of that practitioner’s evidence having regard to that deficiency or argument raised by the appellant [62]. 6. Grounds (a) and (c) concerning the Arbitrator’s findings of neck injury, right shoulder injury and consequential left shoulder condition were made out. Such conclusion 22 required revocation of the Arbitrator’s determination. In the circumstances it was not necessary to consider the other grounds raised by the appellant. However, the Deputy President did give some attention to the remainder of the appellant’s grounds [63]. Ground (b) 7. The appellant was correct in its submission that the evidence of Dr Noll, found in his report dated 19 March 2009, was inadmissible having regard to the terms of reg 49 of the 2010 Regulation. The terms of that Regulation prohibited the admission of Dr Noll’s evidence given that the worker had also adduced evidence from Dr Bodel, whose speciality corresponded to that of Dr Noll. The Arbitrator did not appear to expressly state during proceedings that the report had been admitted. Notwithstanding that fact, reference was made to the evidence in the course of Reasons, albeit that the Arbitrator eschewed any reliance upon that report in reaching his conclusions. The second “order”, noted in the Arbitrator’s “Statement of Reasons Extempore Orders” clearly noted that all documents tendered, including Dr Noll’s report, were admitted [64]. 8. Whilst acceptance of the tender of Dr Noll’s report in contravention of the Regulation constitutes error, the Deputy President did not consider that such error was relevant in that it could not be said that such error relevantly affected the Arbitrator’s decision: s 352(5). The Deputy President reached that conclusion having regard to the Arbitrator’s statement that he placed no reliance upon that evidence in reaching his conclusion [65]. Ground (d) 9. The complaint raised under this ground was addressed where grounds (a) and (c) were addressed above [66]. Ground (e) 10. Complaint was made that the Arbitrator placed reliance upon the hand written notes of Dr Allen in circumstances where no submission had been put by the worker as to the proper construction and relevance of those notes, and the appellant had not had the opportunity to address as to the content of those notes. There is some substance to that complaint. In submissions on this appeal, the appellant disputed the Arbitrator’s interpretation of those notes [67]. 11. The Deputy President’s interpretation of the notes led him to conclude that there was little doubt as to what was there recorded. The notes, however, were in a state of some confusion and one entry of possible relevance appeared to be incomplete. As submitted by the appellant, this matter and any controversy as to the content of the notes, may properly be addressed, should the matter be remitted for hearing afresh [68]. 12. Whilst it is always preferable, and consistent with legislative intent, that a decision be made on appeal in place of the decision revoked, the Deputy President reached the view that the state of the evidence and argument raised required that the matter be remitted to another Arbitrator for consideration afresh [69]. 23