and fallaciously

advertisement

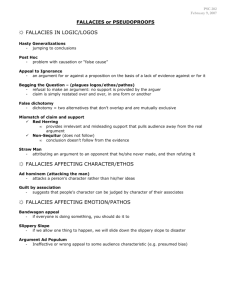

Fallacies A defective inference is said to be ‘fallacious.’ A fallacy is a common pattern of defective reasoning. Fallacies come in two general categories: formal and informal. [see With Good Reason: An Introduction to Informal Fallacies (5th Edition, 1994), by S. Morris Engel. and http://gncurtis.home.texas.net/index.html] 1 Formal Fallacies A formal fallacy is one that is defective purely as a result of the form the argument takes, and one that is easily confused with a valid form. E.g. If Clinton passes that law, he’ll be doing the right thing. Clinton didn’t pass that law. Therefore, Clinton didn’t do the right thing. This form of reasoning is fallacious no matter what the argument is about, and it’s easily confused with modus ponens or tollens. If p then q. Not-p Therefore, not-q. 2 Informal Fallacies An informal fallacy is defective in part because of its content. These are the ones that we will focus on. They are the more interesting and the more common ones. There are lots of interesting inter-relations among these fallacies, but we won’t discuss those in any detail. 3 Three Kinds of Fallacy We’ll look at three kinds of fallacy: 4 Fallcies of clarity Fallacies of relevance Fallacies of vacuity Fallacies of Clarity Reasoning can go wrong because of problems with the language being used. If a term is vague, then the argument in which it is being used may be fallacious. We’ll consider three fallacies of clarity: 5 The sorites argument; The slippery slope argument; and The fallacy of equivocation. The Sorites Argument These kinds of argument are also called: fat man, bald man, and heap arguments. A sorites argument is one that depends on vague terms, and the vagueness leads to many borderline cases. This in turn seems to lead to an absurd conclusion. Suppose I have a full head of hair. I can then argue as follows: 6 The Sorites Argument Someone who has lost one hair is not bald. One cannot become bald by losing one hair. If someone who has lost one hair is not bald, and one cannot become bald by losing one hair, then someone who has lost two hairs is not bald. If someone who has lost two hairs is not bald, and one cannot become bald by losing one hair, then someone who has lost three hairs is not bald. … If someone who has lost 49,999 hairs is not bald, and one cannot become bald by losing one hair, then someone who has lost 50,000 hairs is not bald. But, of course, someone who has lost 50,000 hairs is bald! Where has the argument gone wrong? 7 Slippery Slope Slippery slope arguments (also called arguments of the beard or fallacies of the beard) is closely related to sorites arguments and also exploit vagueness and borderline cases. Here the idea is to argue that because there is no clear differences between cases, there is no real difference between them. 8 Slippery Slope Slippery slope arguments seem to go wrong because they rely on a principle of this kind: If case 1 is not significantly different from case 2, and case 2 is not significantly different from case 3, then case 1 is not significantly different from case 3. This is clearly mistaken — slippery slope arguments demonstrate that! — but it’s not easy to say exactly why. Still, unlike sorites arguments, slippery slope arguments are sometimes used to convince people of particular claims, so they are not merely of theoretical interest. 9 Varieties Conceptual slippery slopes: There is little difference between things at the end of a conceptual continuum. Fairness slippery slopes: It is unfair to treat small differences differently. Causal slippery slopes (also called domino arguments and parades of horrors): Once a particular event occurs, then other similar ones will follow and this will lead to a disaster. 10 Conceptual The law recently passed by the county court explicitly forbids any “motorized vehicles with wheels” in the park. Cars are the intended target, of course, but the law is too vague to exclude cars alone. Motor bikes are not substantiallly different in design and purpose from cars, so they are excluded; but if motor bikes are excluded, so are electric bicycles; and if electric bicycles are excluded, then so are electric scooters; and if electric scooters are exlcuded then so are electric wheelchairs. And if electric wheelchairs are excluded, then the law discriminates against some handicapped people who pay taxes but will not get the benefit of the use of this park. Aside: Success of slippery slopes. 11 Fairness Assisted suicide is morally acceptable because it stops irremediable pain in people who are terminally ill. On these grounds, euthanasia should also be permitted since it is nothing more than an active form of assisted suicide. If someone is chronically ill, they too are suffering irremediable pain, so euthanasia in these cases is also morally acceptable. Since irremediable pain can be psychological as well as physical, euthanasia for psychologist distress is also permissible. Finally, since people suffering irremediable pain are not always the best judge of what is best for them, involuntary euthanasia (called “termination of the patient without explicit request” in the Netherlands) of people suffering irremediable psychological distress is also morally acceptable. 12 Parade of Horrors If today you can take a thing like evolution and make it a crime to teach it in the public schools, tomorrow you can make it a crime to teach it in the private schools, and next year you can make it a crime to teach it in the church. At the next session you can ban books and the newspapers. Ignorance and fanaticism are ever busy, indeed feeding, always feeding and gloating for more. Today it’s the public school teachers, tomorrow the private. The next day the preachers and the lecturers, the magazines, the books, the newspapers. After awhile, your honor, it is the setting of man against man, creed against creed, until the flying banners and beating drums are marching backwards to the glorious ages of the sixteenth century when bigots lighted faggots to burn the man who dared to bring any intelligence, and enlightenment, and culture to the human mind. (Clarence Darrow, cited in Stephen Jay Gould's Hen's Teeth and Horse's Toes, p. 278.) 13 Ambiguity There is more than one way to think about ambiguity. For the purposes of investigating fallacies, it is best to say that a word or phrase is ambiguous when it is misleading or potentially misleading. Ambiguity is the basis of a the fallacy of equivocation where an argument that appears valid or sound only does so because there is ambiguity in the premises. 14 Equivocation What the lawyer said: President Clinton should have been impeached only if he had sexual relations with Monica Lewinsky. He did not have sexual relations with Lewinsky. Therefore, he should not have been impeached. What Clinton meant: President Clinton should have been impeached only if he had sexual intercourse with Monica Lewinsky. He did not have sexual intercourse with Lewinsky. Therefore, he should not have been impeached. What the Congress heard: President Clinton should have been impeached only if he had sexual contact of any kind with Monica Lewinsky. He did not have sexual contact of any kind with Lewinsky. Therefore, he should not have been impeached. 15 Fallacies of Relevance It is a conversational rule that when we offer a reason for a view, it is a relevant reason. When someone says something that is irrelevant that is designed to distract the audience rather than convince them, they are committing a fallacy of relevance (also called ignoratio elenchi — “ignorance of refutation”). We’ll consider two fallacies of clarity: 16 Ad hominem arguments; and Appeals to authority. Ad Hominem Ad hominem is Latin for “against the man.” This is an argument form in which one attacks the person rather than the view she is defending. They are typically (and fallaciously) used to move from features of the arguer to a claim about the truth of the argument’s conclusion or its validity. 17 Aside: Moral Authority Ad hominems can be used reasonably — if not always fairly — when they are used to suggest that the arguer doesn’t have the moral authority to make the argument. E.g. One often hears people saying things like: “What right does a divorced politician have to preach to us about family values!” Stricly speaking, of course, he has every right. His own behavior is strictly irrelevant to the goodness or badness of his arguments. Still, we tend to have the moral — note: not logical view — that he who casts the first stone should be without sin. 18 Ad Hominem Milo: So what does my opponent have to offer to reduce the mounting death toll on our nation’s highways? Opus: Ummm… ‘55 saves lives’! Milo: I see. Apparently my opponent would support saving an additional 45,000 lives per year by reducing the speed limit to 40mph. Opus: Gee, 40 is kinda’ slow…. Milo: Apparently my opponent would send 45,000 innocent civilians to fiery deaths just so he can get to his manicurist five minutes early. Opus: I don’t even have a manicurist! Milo: 19 He probably doesn’t. Most mass-murderers don’t. Hitler didn’t. Tu Quoque One kind of ad hominem turns a criticism back onto the critic. This kind of argument is called tu quoque (Latin for “you, also” or “you’re another”; also “Oh, yeah?” “Yeah!”): Q: Now, the United States government says that you are still funding military training camps here in Afghanistan for militant, Islamic fighters and that you're a sponsor of international terrorism... Are these accusations true?... Osama Bin Laden: …At the time that they condemn any Muslim who calls for his right, they receive the highest top official of the Irish Republican Army at the White House as a political leader, while woe, all woe is the Muslims if they cry out for their rights. Wherever we look, we find the US as the leader of terrorism and crime in the world… (From an interview with Osama Bin Laden by Peter Arnett) 20 Genetic Fallacy Ad hominems can be thought of as a particular kind of genetic fallacy. This is the fallacy of criticizing the source of an argument rather than its content. For example, one might deny the value of someone’s idea because it came to him in a dream. Kekulé’s idea about the structure of benzene came to him in a dream, but it was a good idea. Qu i ck Ti me ™a nd a TIFF (Unc om pres se d) de co mp re ss or are n ee de d to s ee th is pi ctu re . In ad hominems the source is the person themselves. 21 Ad Hominem Aside: There is a different kind of ad hominem argument which is not fallacious (and indeed is extremely effective). In this argument you argue from premises that Jones himself believes that Jones ought to believe something else (or that he shouldn’t believe something he does believe). This is ad hominem because it is directed at the person’s beliefs (not at irrelevant facts about them). Smith to Jones: “I’m not a vegetarian myself, but you are because you believe it is wrong to use animals for our own purposes. If that’s true, then you shouldn’t be wearing those (very attractive) leather shoes.” 22 Appeals to Authority We often cite authorities to back up our views. This is often perfectly reasonable. Authorities, properly understood, are those people best placed to make a judgement about their area of expertise Often, however, the “authorities” cited are either not experts in the field they are commenting on, or not experts at all. To decide whether an appeal to authority is fallacious or not, one has to decide whether the authority is an appropriate one. 23 Appeals to Authority “Mars Rocks and Magnetotactic Bacteria: Life on Mars?” E. Imre Friedmann, a biologist at NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif., said an electron microscope examination of [the Mars rock] ALH84001 had produced evidence of magnetite crystals formed in chains. Friedmann said that on Earth the bacteria that make magnetite forms the material in chains and that these chains are surrounded by a membrane. Under the electron microscope, fossilized images of both the chains and the membrane can be seen, he said. “We see chains that could have been formed only biologically,” said Friedmann. “There is no way you could come up with a non-biological explanation.” 24 Appeals to Authority “In Vitro Fertilization and Single Women” E. Imre Friedmann, a biologist at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif., said that God intended for children to be born as a result of natural processes and to be raised by a mother and a father. “There is no way you could come up with a non-natural method of reproduction that God would approve of” Friedman said. [Note: this example is made up!] 25 Related Fallacies Appeal to popular opinion (the bandwagon fallacy; argumentum ad populam; or appeal to tradition when the view has been long shared) “See America's favorite upright vacuum cleaner at your Hoover dealer. Like millions of women, you'll like the basic Hoover and its honest value.” 26 Related Fallacies The appeal to ignorance offers the absence of evidence for some claim as evidence in favor of its negation: There is no evidence that air quality is deteriorating in LA. Therefore, air quality is not deteriorating in LA. This is a from of argument whose success depends on background. If a substantial investigation into air quality in LA has been done, and no evidence of deterioration has been found, then this is indeed evidence that the air is not worsening. But the mere absence of evidence for a claim is not of itself evidence for the negation of that claim. 27 Related Fallacies An appeal to pity or emotion tries to provide support for a conclusion based on emotional considerations rather than considerations of good reasons: My parents are crazy; I had a job as a hand model, but I burnt my hands; my girlfriend saw me naked after I had been swimming and there was shrinkage; therefore I deserve this apartment more than the person who got here first. 28 Fallacies of Vacuity Finally, we’ll look at fallacies of vacuity. We’ll consider three: 29 Circular reasoning; Begging the question; and Self-sealers. Circular Reasoning Fodor’s argument that p My argument for p is based on three premises: 1. q 2. r and 3. p From these, the claim that p deductively follows. Some people may find the third premise controversial, but it is clear that if we replaced that premise by any other reasonable premise, the argument would go through just as well. 30 Circular Reasoning Any argument in which the conclusion — or something equivalent to the conclusion — is used as a premise. Notice that circular arguments are valid! They have this form: p p If p happens to be true, the argument is sound! So circular arguments and their ilk are exceptions to the claim that sound arguments are good arguments. 31 Begging the Question A closely related form of reasoning is called begging the question (or petitio principii). Aside: A linguistic note. A premise or argument (or person) begs the question when it relies on a premise that is not supported by any reason that is independent of the conclusion; and such a reason is needed. 32 Begging the Question “To cast abortion as a solely private moral question,...is to lose touch with common sense: How human beings treat one another is practically the definition of a public moral matter. Of course, there are many private aspects of human relations, but the question whether one human being should be allowed fatally to harm another is not one of them. Abortion is an inescapably public matter.” (Helen M. Alvaré, The Abortion Controversy, Greenhaven, 1995, p. 23.) 33 Begging the Question Abortion is characterized as fatally harming a human being. And: “[h]ow human beings treat one another is practically the definition of a public moral matter.” So the conclusion that abortion is a matter of public morality depends, like the first premise, on the claim that the fetus is a person. Since that is a controversial matter, an independent justification for the premise is required but not given. The premise (and argument) therefore begs the question. 34 Begging the Question Note again that arguments that beg the question are valid: if the premises are true, then the conclusion must be. E.g.: God wrote the Bible. God exists. Arguments that beg the question are therefore special cases of defective arguments. 35 Self-Sealers A self-sealer is a position that cannot be refuted. It is said to be empty of vacuous. Since self-sealers are, by definition, unresponsive to any evidence, they are not based on rational procedures and ought to be rejected. Ideologies, prejudices, and clinical delusions tend to be self-sealers. 36