Airway Management An Introduction and Overview

Airway Management:

An Introduction and Overview

&

Massive Hemoptysis

Division of Critical Care Medicine

University of Alberta

Airway Management

Outline

Overview

Normal airway

Difficult intubation

Structured approach to airway management

Causes of failed intubation

Overview of the Airway

600 patients die per year from complications related to airway management

3 mechanisms of injury:

1.

2.

3.

Esophageal intubation

Failure to ventilate

Difficult Intubation

98% of Difficult Intubations may be anticipated by performing a thorough evaluation of the airway in advance

Indications for Intubation

Ventilatory Support

Decreased GCS

Protection of Airway

Ensuring Airway patency

Anesthesia and surgery

Suctioning and Pulmonary Toilet

Hypoxic and Hypercarbic respiratory Failure

Pulmonary lavage

Endotracheal Intubation Depends

Upon Manipulation of:

Cervical spine

Atlanto-occipital Joint

Mandible

Oral soft tissues

Neck hyoid bone

Additionally:

Dentition

Pathology - Acquired and

Congenital

The Normal Airway

History of one or more easy intubations w/o sequelae

Normal appearing face with regular features

Normal clear voice

Absence of scars, burns, swelling, infections, tumour, or hematoma

No history of radiation of the head or neck

Ability to lie supine asymptomatically; no history of snoring or sleep apnea

The Normal Airway

Patent nares

Ability to open mouth widely with TMJ rotation and subluxation (3 – 4 cm or two finger breaths)

Mallampati Class I

Patient sitting straight up, opening mouth as wide as possible, with protruding tongue; the uvula, posterior pharyngeal wall, entire tonsillar pillars, and fauces can be seen

At least 6 cm (3 finger breaths) from tip of mandible to thyroid notch with neck extension

At least 9 cm from symphysis of mandible to mandible angle

The Normal Airway

Slender supple neck w/o masses; full range of neck motion

Larynx moveable with swallowing and manually moveable laterally (about 1.5 cm each side)

Slender to moderate body build

Ability to extend atlanto-occipital joint

(normal extension is 35 ° )

Risk Factors For Difficult

Intubation

El-Canouri et al. - prospective study of 10, 507 patients demonstrating difficult intubation with objective airway risk criteria

Mouth opening < 4 cm

Thyromental distance < 6 cm

Mallampati grade 3 or greater

Neck movement < 80%

Inability to advance mandible (prognathism)

Body weight > 110 kg

Positive history of difficult intubation

Signs Indicative of a Difficult

Intubation

Trauma, deformity: burns, radiation therapy, infection, swelling, hematoma of face, mouth, larynx, neck

Stridor or air hunger

Intolerance in the supine position

Hoarseness or abnormal voice

Mandibular abnormality

Decreased mobility or inability to open the mouth at least 3 finger breaths

Micrognathia, receding chin

Treacher Collins, Peirre Robin, other syndromes

Less than 6 cm (3 finger breaths) from tip of the mandible to thyroid notch with neck in full extension

< 9 cm from the angle of the jaw to symphysis

Increased anterior or posterior mandibular length

Signs Indicative of a Difficult

Intubation

Laryngeal Abnormalities

Fixation of larynx to other structures of neck, hyoid, or floor of mouth.

Macroglossia

Deep, narrow, high arched oropharynx

Protruding teeth

Mallampati Class 3 and 4

Signs Indicative of a Difficult

Intubation

Neck Abnormalities

Short and thick

Decreased range of motion (arthritis, spondylitis, disk disease)

Fracture (subluxation)

Trauma

Thoracoabdominal abnormalities

Kyphoscoliosis

Prominent chest or large breasts

Morbid obesity

Term or near term pregnancy

Age 50 – 59

Male gender

Difficult Intubation - History

Previous Intubations

Dental problems (bridges, caps, dentures, loose teeth)

Respiratory Disease (sleep apnea, smoking, sputum, wheeze)

Arthritis (TMJ disease, ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis)

Clotting abnormalities (before nasal intubation)

Congenital abnormalities

Type I DM

NPO status

Difficult Intubation - Diabetes

Mellitus

Difficult intubation 10 x higher in long term diabetics

Limited joint mobility in 30 – 40 %

Prayer sign

Unable to straighten the interpharyngeal joints of the fourth and fifth fingers

Palm Print

100% sensitive of difficult airway

Difficult Intubation - Physical Exam

General:

LOC, facies and body habitus, presence or absence of cyanosis, posture, pregnancy

Facies:

Abnormal facial features

Pierre Robin

Treacher Collins

Klippel – Feil

Apert’s syndrome

Fetal Alcohol syndrome

Acromegaly

Nose:

For nasal intubation

Patency

Pierre Robin

Treacher Collins

Difficult Intubation - Physical Exam

TMJ Joint – articulation and movement between the mandible and cranium

Diseases:

Rheumatoid arthritis

Ankylosing spondylitis

Psoriatic arthritis

Degenerative join disease

Movements: rotational and advancement of condylar head

Normal opening of mouth 5 – 6 cm

Difficult Intubation - Physical Exam

Oral Cavity

Foreign bodies

Teeth:

Long protruding teeth can restrict access

Dental damage 25% of all anesthesia litigations

Loose teeth can aspirate

Edentulous state

Rarely associated with difficulty visualizing airway

Tongue:

Size and mobility

Mallampati Classification

Class I: soft palate, tonsillar fauces, tonsillar pillars, and uvuala visualized

Class II: soft palate, tonsillar fauces, and uvula visualized

Class III: soft palate and base of uvula visualized

Class IV: soft palate not visualized

Class III and IV Difficult to Intubate

Mallampati Classification

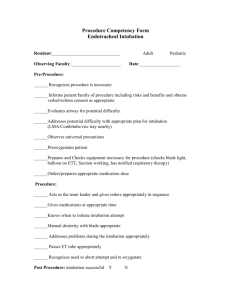

Structured Approach to Airway

Management

MOUTHS

Component Description

Mandible Length and subluxation

Opening Base, symmetry, range

Uvula

Teeth

Visibility

Dentition

Assessment Activities

Measure hyomental distance and anterior displacement of mandible

Assess and measure mouth opening in centimetres

Assess pharyngeal structures and classify

Assess for presence of loose teeth and dental appliances

Assess all ranges and movement Head Flexion, extension, rotation of head/neck and cervical spine

Silhouette Upper body abnormalities, both anterior and posterior

Identify potential impact on control of airway of large breasts, buffalo hump, kyphosis, etc.

Bag/Valve/Mask Ventilation

Always need to anticipate difficult mask ventilation

Langeron et al. 1502 patients reported a 5% incidence of difficult mask ventilation

5 independent risk factors of difficult mask ventilation:

Beard

BMI > 26

Edentulous

Age > 55 years of age

History of snoring (obstruction)

Two of these predictors of DMV

Sensitivity and specificity > 70%

DMV Difficult Intubation in 30% of cases

Intubation Technique

Preparation:

Equipment Check

100% oxygen at high flows (> 10 Lpm) during

bask/mask ventilation

Suction apparatus

Intubation tray

Two laryngoscopic handles and blades

Airways

ET tubes

Needles and syringes

Stylet

KY Jelly

Suction Yankauer

Magill Forceps

LMA’s

Pre - oxygenation

Traditional:

3 minutes of tidal volume breathing at 5 ml/kg 100%

O

2

Rapid

8 deep breaths within 60 seconds at 10 L/min

Always ensure pulse oximetry on patient

Positioning

Optimal Position – “sniffing position”

Flexion of the neck and extension of the antlantooccipital joint

Mandible and Floor of Mouth

Optimal position:

flexing neck and extending the atlantooccipital joint

Positioning

Positioning

Factors that Interfere with

Alignment

Large teeth or tethered tongue

Short mandible

Protruding upper incisors

Pathology in floor of mouth

Reduced size of intra and sub mandibular space

Practical Note: Thyromental distance 6 cm or 3 finger breaths should show

Normal mandible

Visualization

Visualization

Insert blade into mouth

Sweep to right side and displace tongue to the left

Advance the blade until it lies in the valeculla and then pull it forward and upward using firm steady pressure without rotating the wrist

Avoid leaning on upper teeth

May need to place pressure on cricoid to bring cords into view

Visualization

Visualization

Laryngoscopy Grade

Grade I - 99%

Grade II - 1%

Grade III - 1/2000

Grade IV - 1/ 10,000

Insertion

Insert cuff to ~ 3 cm beyond cords

Tendency to advance cuff too far

Right mainstem intubation

Cuff Inflation

Inflate to 20 cm H

2

O

Listen for leak at patients mouth

Over inflation can lead to ischemia of trachea

Confirmation ETT Position

Continuous CO

2

Gold standard monitoring or capnometry

Must have at least 3 continuous readings without declining CO

2

False Negative Results

Tube in Trachea, Capnogram Suggests Tube in

Esophagus

Concurrent PEEP with ETT cuff leak

Severe Airway obstruction

Low Cardiac Output

Severe hypotension

Pulmonary embolus

Advanced pulmonary disease

False Positive Results

Tube NOT in trachea, capnogram suggests tube in trachea

Bag/valve/mask ventilation prior to intubation

Antacids in stomach

Recent ingestion of carbonated beverages

Tube in pharynx

False Positive Results

Other Methods to Determine

Placement of ETT tube

Auscultation

Visualization of tube through cords

Fiberoptic bronchoscopy

Pulse oximetry not improving or worsening

Movement of the chest wall

Condensation in ET tube

Negative Pressure Test

CXR

Airway Maneuvers

1.

2.

3.

4.

BURP – Improves visualization of airway

Posterior pressure on the larynx against cervical vertebrae (Backward)

Superior pressure on the larynx as far as possible

(Upward)

Lateral pressure on the larynx to the right (Right)

With pressure (Pressure)

Causes of Failed Intubation

Poor positioning of the head

Tongue in the way

Pivoting laryngoscope against upper teeth

Rushing

Being overly cautious

Inadequate sedation

Inappropriate equipment

Unskilled laryngoscopist

Summary

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

600 patients die per year from complications related to airway management

3 mechanisms of injury:

1.

2.

3.

Esophageal intubation

Failure to ventilate

Difficult Intubation

Indication for intubation:

Ventilatory Support

Decreased GCS

Protection of Airway

Ensuring Airway patency

Anesthesia and surgery

Suctioning and Pulmonary Toilet

Hypoxic and Hypercarbic respiratory Failure

Pulmonary lavage

Massive Hemoptysis

Massive Hemoptysis

More than 300 to 600 ml of blood in 12 to

24 hours.

Difficult to assess the actual amount.

Life threatening bleeding into the lung can occur without actual hemoptysis.

Causes of Hemoptysis and

Pulmonary Hemorrhage

Localized bleeding

Diffuse Bleeding

Localized Bleeding

Infections

Bronchitis

Bacterial Pneumonia

Streptococcus and

Klebsiella

Tuberculosis

Fungal Infections

Aspergillus

Candida

Bronchiectasis

Lung Abscess

Leptospirosis

Tumors

Bronchogenic

Squamous

Necrotizing parenchymal cancer

Adenocarcinomas

Bronchial adenoma

Cardiovascular

Mitral Stenosis

Localized Bleeding

Pulmonary

Vascular Problems

Pulmonary AV malformations

Rendu-Osler-Weber

Syndrome

Pulmonary embolism with infarction

Behcet syndrome

Pulmonary artery catheterization with pulmonary artery rupture

Trauma

Others

Broncholithiasis

Sarcoidosis (cavitary lesions with mycetoma)

Ankylosing spondylitis

Diffuse Bleeding

Drug and chemical

Induced

Anticoagulants

D-penicillamine (seen with treatment of Wilson’s disease)

Trimellitic anhydride

(manufacturing of plastics, paint, epoxy resins)

Cocaine

Propylthiouracil

Amiodarone

Phenytoin

Hemosiderosis

Blood dyscrasias

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

Hemophilia

Leukemia

Thrombocytopenia

Uremia

Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome

Pulmonary – Renal Syndrome

Goodpasture syndrome

Wegener granulomatosis

Pauci-immune vasculitis

Diffuse Bleeding

Vasculitis

Pulmonary capillaritis

With or without connective tissue disease

Polyarteritis

Churg-Strauss syndrome

Henoch-Schonlein Purpura

Necrotizing vasculitis

Connective Tissue diseases

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Rheumatoid arthritis

Mixed connective tissue disease

Scleroderma (rare)

Key Major Etiologies

Tuberculosis

Bronchiectasis

Cancer

Mycetoma

Iatrogenic causes

Alveolar Hemorrhage

Trauma

Vascular malformation

Pulmonary embolism

Other Infectious Causes

Pathophysiology

Bronchial circulation

High (systemic) pressure circulation

Drains into the right atrium (extrapulmonary bronchi)

Also drains into pulmonary veins (intrapulmonary bronchi)

Anterior spinal artery may originate from bronchial artery (5% of cases)

Pulmonary circulation

Low-pressure circulation

Multiple anastomoses exist between bronchial and pulmonary circulations

Clinical Findings

Hemoptysis, Dyspnea, Cough, Anxiety

Fever, weight loss

Smoking and Travel history

Bloody sputum

Frothy blood – sputum mixture

Bright red

Alkaline

Tachypnea, respiratory distress

Localized wheezing, rales, poor dentition

Digital clubbing

Hematuria

Differential Diagnosis

Upper GI Bleeding

Dark blood

Food particles

Acid pH

Consider endoscopy

Upper airway bleeding

Examine mouth, nose, and pharynx.

Laboratory Tests

No specific tests

CBC, diff, INR, PTT, platelet count

Electrolytes, BUN, Cr

Sputum culture and AFB

Urinalysis

ECG

ABG’s

Type and Screen

Imaging Studies

Chest X-ray

Normal suggests endobronchial or extrapulmonary source.

Potentially misleading

Aspiration from distant source

Chronic changes unrelated to acute event

CT scan

Useful in stable patients

Can detect bronchiectasis

Stabilization

Ensure adequate ventilation and perfusion.

Most common cause of death is asphyxia.

Place patient in Trendelenburg position to facilitate drainage.

Lateral decub – Bleeding side down

Prevent contamination of good lung.

Treatment

1.

2.

General Measures:

Place bleeding lung down to prevent aspiration into good lung

Supplemental oxygen

3.

4.

5.

6.

Avoid Sedation

Correct coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia

Consult pulmonary, critical care, and thoracic surgery

Consider early involvement of anesthesia and interventional radiology

Primary Goal is Airway Control

Asphyxiation, not blood loss, is the cause of death.

Only stable patients with ability to protect and clear their own airway should be managed without intubation.

Intubation:

Performed by experienced personnel.

Large bore tube for bronchoscopy and suctioning.

Consider bronchial blocker or double lumen tube if bleeding site is known.

Secondary Goal is Localization of

Bleeding

Bronchoscopy required.

Intubate prior to bronchoscopy.

Rigid bronchoscopy

May facilitate better suctioning.

Inability to visualize beyond main stem bronchi and need thoracic surgeon.

Bronchoscopic Interventions

Bronchial blocker or Fogarty balloon catheter to occlude bleeding lung, lobe, or segment.

Topical coagulants:

Fibrin or fibrinogen-thrombin solution.

Topical transexamic acid

Consider Nd:YAG laser coagulation, electrocautery, or argon plasma coagulation.

Lavaged iced saline

Topical epinephrine

Unilateral Lung Ventilation

Single lumen tube advanced into main stem bronchus.

Double lumen tube:

Protects non-bleeding lung.

Use left sided tube to prevent occlusion of Right upper lobe.

May be difficult to position.

Individual lumens too small for standard bronchoscope.

Airway obstruction frequent problem.

Displacement can lead to sudden asphyxiation.

Patient should be therapeutically paralyzed and not moved.

Bronchial Arteriography and

Embolization

Favored initial approach if facilities and expertise available.

High success rate: approximately 90% when a bleeding vessel is identified.

Recurrence rate: 10 – 27%

10% of patients bleed from the pulmonary circulation

(TB or mycetoma).

Serious complications:

Occlusion of the anterior spinal artery with paraplegia.

Embolic infarction of distal organs.

Early Surgical Treatment

Offers definitive treatment.

Indicated for lateralized massive life-threatening hemoptysis, or failure or recurrence after other interventions.

Contraindications:

Poor baseline respiratory function.

Inoperable lung carcinoma.

Inability to localize bleeding site.

Diffuse lung disease (relative) eg. CF.

Mortality is higher if bleeding is acute

Late Surgical Treatment

Indicated for definitive treatment of underlying lesion, once bleeding subsided.

Indications:

Mycetoma

Resectable carcinoma

Localized bronchiectasis

Prognosis

Factors likely affecting outcome

Etiology of hemoptysis

Underlying co-morbid illnesses

Surgical vs. medical treatment

Mortality

Medical mortality: 17 – 85%

Estimated early surgical mortality: 0 – 50%

Most case series reports preceded the development of angiographic embolization.

Conclusion

More than 300 to 600 ml of blood in 12 to 24 hours.

Major causes:

Tuberculosis

Bronchiectasis

Cancer

Mycetoma

Iatrogenic causes

Alveolar Hemorrhage

Trauma

Vascular malformation

Pulmonary embolism

Primary goal is airway control followed by bleeding localization.