File

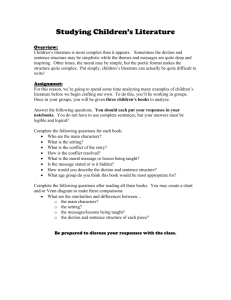

advertisement

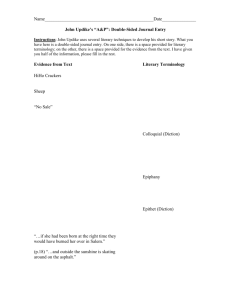

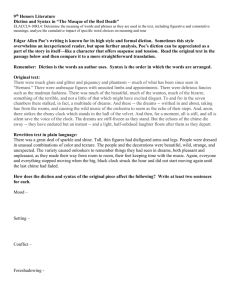

Unit 2 Rhetorical Strategies 1 What are Rhetorical Strategies? • Rhetorical strategy: – a loose term for techniques that help to shape or enhance a literary work. • Rhetorical strategies include: – – – – – – – – 2 Allusion Analogy Imagery Symbolism Atmosphere Repetition Selection and order of details Epiphany Diction • Diction (from the Latin word for “to say”) denotes the word choice and phrasing in a literary work. o o o o 3 Formal vs. colloquial Abstract vs. concrete Literal vs. figurative Latin vs. Anglo-Saxon Formal Diction The spring, indeed, did often come without any of those effects, but he was always certain that the next would be more propitious; nor was ever convinced that the present spring would fail him before the middle of summer; for he always talked of the spring as coming till it was past, and when it was once past, everyone agreed with him that it was coming. By long converse with this man, I am, perhaps, brought to feel immoderate pleasure in the contemplation of this delightful season; but I have the satisfaction of finding many, whom it can be no shame to resemble, infected with the same enthusiasm; for there is, I believe, scarce any poet of eminence, who has not left some testimony of his fondness for flowers, the zephyrs, and the warblers of the spring. Nor has the most luxuriant imagination been able to describe the serenity and happiness of the golden age, otherwise than by gaining a perpetual spring, as the highest reward of uncorrupted innocence. ---Rambler No. 5 by Samuel Johnson 4 Colloquial Diction The bus climbed steadily up the road. The country was barren and rocks stuck up through the clay. There was no grass beside the road. Looking back we could see the country spread out below. Far back the fields were squares of green and brown on the hillsides. Making the horizon were the brown mountains. They were strangely shaped. As we climbed higher the horizon kept changing. As the bus ground slowly up the road we could see other mountains coming up in the south. Then the road came over the crest, flattened out, and went into a forest. It was a forest of cork trees, and the sun came through the trees in patches, and there were cattle grazing back in the trees. We went through the forest and the road came out and turned along a rise of land, and out ahead of us was a rolling green plain, with dark mountains beyond it. These were not like the brown, heat-baked mountains we had left behind. These were wooded and there were clouds coming down from them. The green plain stretched off. ---from The Sun Also Rises, Hemingway 5 Trying to Sound Smart • In The Adventures of Huck Finn, Mark Twain exposes the fraudulent credentials of “the king” – “the king” is a rascal who first claimed to Huck that he is descended from French royalty. • He poses as a British clergyman in a scheme to abscond with the fortune left by a man who, he claims, was his brother. • In eulogizing the “diseased” (deceased), he says how fitting it is for so charitable a person that his “funeral orgies sh’d be public.” • His equally corrupt friend “the duke” is considerably more learned than his partner, and his mistakes anger him. However, he is posing as a deaf mute, so he cannot cut off the ignorant oration. Huck describes the scene: • 6 Trying to Sound Smart And so he [the king] went a mooning on and on, liking to hear himself talk, and every little while he fetched in his funeral orgies again, till the duke he couldn’t stand it no more; so he writes on a little scrap of paper, “obsequies, you old fool,” and folds it up and goes to goo-gooing and reaching it over people’s heads to him. 7 Trying to Sound Smart • The king is not deterred. He misuses the term three more times, and then gives the following explanation: “I say orgies, not because it’s a common term, because it ain’t—obsequies bein’ the common term—but because orgies is the right term. Obsequies ain’t used in England no more—it’s gone out. We say orgies, now, in England. Orgies is better, because it means the thing you’re after, more exact. It’s a word that’s made up out’n the Greek, orgo, outside, open, abroad; and the Hebrew jeesum, to plant, cover up; hence inter. So, you see, funeral orgies is an open er public funeral.” 8 Abstract or Concrete? • A writer’s diction may also differ enormously in its relative levels of abstraction—the extent to which it deals with general concepts—or of concreteness: with physical objects, imagery, and emotive and sensual details. • 9 Abstract • • • • • Love Beauty Patriotism Time 10 Concrete • • • • • Lips Gun Silky gown Shrill cry 11 Abstract and Concrete • Most literary works contain both abstract and concrete diction, in varying degrees. • Often a writer will illustrate an abstract concept with concrete details. • 12 Example • In John Keats’s “Ode to a Nightingale,” the narrator describes with increasingly concrete diction a magical wine that could make him oblivious to life’s sufferings: O, for a draught of vintage! That hath been Cooled a long age in the deep-delved earth, Tasting of Flora and the country green, Dance, and Provencal song, and sunburnt mirth! O for a beaker full of the warm South, Full of the true, the blushful Hippocrene, With beaded bubbles winking at the brim, And purple-stained mouth. 13 Abstract Concepts and Themes • A writer might also imply an abstract concept or theme, which must be inferred from a series of concrete descriptions or images. One had a cat’s face One a whisked tail, One tramped at a rat’s pace One crawled like a snail. ---Christina Rossetti “Goblin Market” 14 Abstract Concepts and Themes • The afflicted maiden implies the addictive nature of the goblins’ wares as she recalls the temperature, texture, look, and taste of the fruit that she longs to savor again: What melons icy-cold Piled on a dish of gold Too huge for me to hold, What peaches with a velvet nap, Pellucid grapes without one seed; Odorous indeed must be the mead Whereon they grow, and pure the wave they drink With lilies at the brink, And sugar-sweet their sap. 15 Hmmm. • The level of diction depends partly on the context in which it is being used. • A philosophical treatise would tend to use words that are formal, often Latinate and abstract. • A lyric poem would likely be more colloquial and concrete. • Of course there are exceptions! • 16 Example • From “Ulysses” by Alfred Lord Tennyson: Though much is taken, much abides; and though We are not now that strength which in old days Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are— One equal temper of heroic hearts, Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield. 17 Poetic Diction • Poetic Diction: phrasing and vocabulary that are characteristic of poetry, as distinguished from the informality of everyday speech. • Words such as, “lo,” “abide,” and “ere” • Poetic contractions such as “ne’er” for “never” “tis” for “it is” and “morn” for “morning” • Emphasis on figurative rather than literal language. • 18 Poetic Diction • Refers to the style favored by neoclassical poets of the 18th century, such as Alexander Pope and Thomas Gray. • They believed that the guiding principle for poetic diction was “decorum”—highly formal word choice suitable to a lofty subject and a refined audience. • 19 Poetic Diction • Characteristics include: o Archaic phraseology, modeling Greek and Roman literature and the poetry of Edmund Spenser and John Milton o A Latinate, rather than Anglo-Saxon, vocabulary o Frequent personification of abstract qualities o Periphrasis o 20 Example of Neoclassic Poetic Diction Can storied urn or animated bust Back to its mansion call the fleeting breath? Can Honor’s voice provoke the silent dust, Or Flattery soothe the dull cold ear of Death? Perhaps in this neglected spot is laid Some heart once pregnant with celestial fire; Hands that the rod of empire might have swayed, Or waked to ecstasy the living lyre. But Knowledge to their eyes her ample page Rich with the spoils of time did ne’er unroll; Chill Penury repressed their noble rage And froze the genial current of the soul. 21 Romantics • When we read the poetry of the Romantic period, we will look for resistance to the Neoclassical norms. • 22 Allusion • Allusion: (from the Latin word for “to play with”) is a passing reference in a work of literature to another literary or historical work, figure, or event, or to a literary passage. • The reference is not explained, so that it can convey the flattering presumption that the reader shares the writer’s erudition or inside knowledge. • 23 Example • In Andrea Lee’s novel Sarah Phillips (1984), the narrator describes her Harvard roommate, a chemistry major and “avid lacrosse player” who “adored fresh air and loathed reticence and ambiguity,” as having the following surprising predilection: Margaret, the scientist, had…a positively Bronteesque conception of the ideal man.” 24 Example • The title of William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury (1929) presents a more complex example. • It alludes to the soliloquy in Shakespeare’s Macbeth in which the embittered protagonist dismisses all of life as merely “a tale/told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,/signifying nothing.” • 25 Other Uses • Allusion can also create ironic deflation. • In T. S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” the insecure narrator, feeling hopelessly inadequate in polite society, says of his efforts to court women: …though I have wept and fasted, wept and prayed, Though I have seen my head (grown slightly bald) brought in upon a platter I am no prophet—and here’s no great matter… 26 More Prufrock • Later in the poem, Prufrock further denigrates his own worth by alluding to the hero of Shakespeare’s Hamlet: “No! I am not Prince Hamlet, nor was meant to be.” • Rather, he claims, he is merely “an attendant lord,…deferential, glad to be of use,” or even, occasionally, “the fool,” the court jester among the dramatis personae. • 27 Final Allusion Notes • Other allusion may be more obscure, either because they refer to highly specialized areas or because they describe people and events known only to a small circle of the writer’s intimates. • 28 Analogy • An analogy (from the Greek word for “proportionate”) is the comparison of a subject to something that is similar to it in order to clarify the subject’s nature, purpose, or function. • 29 Analogy • Science often uses analogies to describe bodily processes, such as comparing the liver to a filter to explain its function of removing wastes from the bloodstream. • 30 Literary Example • In Orwell’s autobiographical essay “Shooting an Elephant,” which is about an incident that occurred when he was a young military policeman in Burma, he faces an agonizing decision about whether to kill an elephant that had gone on a rampage but is now calm. Before delving into the complex moral, political, and emotional ramifications of the situation, the narrator uses an analogy to clarify for his Western audience its simple economic aspect: • 31 Example As soon as I saw the elephant I knew with perfect certainty that I ought not to shoot him. It is a serious matter to shoot a working elephant—it is comparable to destroying a huge and costly piece of machinery. 32 Another Example • In Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness (1902) he makes a lengthy analogy: • 33 It’s looooong. Sorry. Imagine the feelings of a commander of a fine—what d’ye call ‘em—trireme in the Mediterranean, ordered suddenly to the north; run overland across the Gauls in a hurry; put in charge of one of these craft the legionaries…used to build, apparently by the hundred, in a month or two, if we may believe what we read. Imagine him here—the very end of the world, a sea the colour of lead, a sky the colour of smoke, a kind of ship about as rigid as a concertina—and going up this river with stores, or orders, or what you like. Sandbanks, marshes, forests, savages, precious little fit to eat for a civilised man, nothing but Thames water to drink. No Falernian wine here, no going ashore. Here and there a military camp lost in the wilderness like a needle in a bundle of hay—cold, fog, tempests, disease, exile, and death—death skulking in the air, in the water, in the bush. They must have been dying like flies here. Oh yes—he did it. Did it very well too, no doubt, and without thinking much about it either, except afterwards to brag of what he had gone through in his time, perhaps. They were men enough to face the darkness….Or think of a decent young citizen in a toga—perhaps too much dice, you know—coming out here in the train of some prefect, or tax-gatherer, or trader even—to mend his fortunes. Land in a swamp, march through the woods, and in some inland post feel the savagery. The utter savagery had closed round him—all that mysterious life of the wilderness that stirs in the forest, in the jungles, in the hearts of wild men. There’s no initiation either into such mysteries. He has to live in the midst of the incomprehensible which is also detestable. And it has a fascination too, that goes to work upon him. The fascination of the abomination—you know. Imagine the growing regrets, the longing to escape, the powerless disgust, the surrender—the hate. 34 Purpose • The analogy serves two purposes: – To get the fictional audience for Marlow’s tale, as well as the larger audience of the readers, into the mindset for understanding the physical and psychological challenges for so-called “civilized” people of venturing into an utterly primitive place. – It also foreshadows the terror, disorientation, and corruption that he will discover in the jungle, the human “heart of darkness” that emerges in a primal setting. – 35