The Case of the Senegal River Basin

The GEF International Waters Learning Exchange and Resource

Network (IWLEARN): Strengthening Transboundary Waters

Management via information sharing and learning among stakeholders – Bangkok, Nov. 20 th 2004

The Case of the Senegal River Basin

By Madiodio Niasse

IUCN-West Africa

Focus of Presentation:

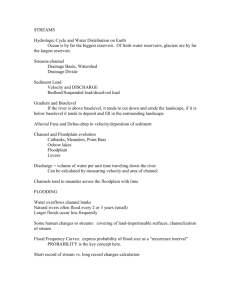

– Debates on efficient and sustainable water allocation & management in a transboundary river context

– Lessons from the Senegal River Basin experience on reconciling development and conservation imperatives

Introduction

—Why SRV

One of the most studied river basins in Africa

The basin organisation

OMVS

generally considered as a

“success story ” of transboundary cooperation on water management

Context in the basin has enabled innovative thinking and experiments :

• OMVS model has inspired many efforts towards transboundary cooperation on Water (SADC Water Protocol; NBI; etc…);

• OMVS hosts the Secretariat of the African Network of Basin Organisations and has organised the two G.A. of ANBO held so far (in 2002 and in Nov

2004);

• Adoption of the first ever River Basin Water Charter in SSA(1992);

• Establishment of an Observatory of the Environment;

• Trailblazing role on the thinking on ecosystem water needs and on ways of responding to such needs while pursuing development objectives : testing of artificial flood releases from dams

Introduction —Presentation of the SRV

• River is 1800 km long: the second longest river in West

Africa after Niger River

• The basin is 300 Sq km shared by

Guinea (11%), Mali (53%),

Mauritania (26%) and Senegal (10%)

• Population of the basin estimated at

2,5 million people , 85% of which live near the river

• In the upper basin, SR is formed by three main contributaries :

Bafing (contributing about 50% of the river flow), Bakoye and

Faleme

• From Bakel (800 km from its mouth) the river meanders in the low lands of the middle valley where it forms a huge and fertile floodplain

• Each year, toward the end of the rainy season (August to October), the floodplain is inundated by the floodwater of the Senegal River

• Area annually inundated can reach

500,000 ha during years of high rainfall in the upper basin

Source: OMVS

STRUCTURE OF PRESENTATION

1. The OMVS Programme & its environmental and

Socio-economic Impacts of the OMVS

Programmes: Diama and Manantali Dams

2. OMVS initial reactions to unanticipated adverse impacts of river flow alteration

3. Realising the true benefits of associated to the natural annual flood

4. Constraints to defining and “implementing managed flow”

5. Way Forward

6. Lessons learned

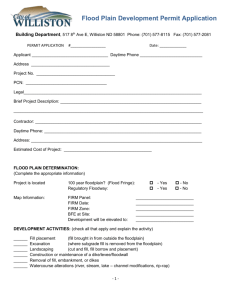

1. THE OMVS PROGRAMME

(1 of 4)

• OMVS (Senegal River Basin Development Authrority) has been established in 1992 with the objective of promoting the cooperation between Mali, Mauritania and Senegal in the development of the Senegal River in order to respond drought conditions that the Sahelian countries were then confronted with

• Three key agreements

• Convention establishing OMVS

• Convention declaring the Senegal River an “international water course”

• Convention declaring the joint infrastructure investments as common properties of the OMVS member states

1. THE OMVS PROGRAMME

(2 of 4)

• The Programme, mainly through Diama and

Manantali Dams (commissioned in 1986 & 1988)

375,000 ha of land to be made available for irrigation

800 GWh/year of hydropower production

Year long navigability of the Senegal river from its month

(Senegal) to Kayes (Mali) situated 800 km upstream

1. THE OMVS PROGRAMME

(3 of 4)

1.1. Initial Impacts of Diama and Manantatli Dams on the

SRV Floodplain : The case of Coastal Floodplain (the

Diawling floodplain):

• Termination of flooding of the lower valley of right bank, which includes the Diawling floodplain, which then became a quasidesert area;

• Destruction of the estuarine and mangrove ecosystems as a result of the stoppage of the mixing of fresh and salt waters;

• Spectacular increase in soil salinity in some low-lying parts of the floodplain that continued to be inundated by the influx of seawaters, this resulting from the combined effects of termination of seasonal natural floods and “separation” fresh and salt waters

• Proliferation of aquatic weeds

(Typha, Salvinia molesta, etc.) as a result of the permanent storage of water behind the dam

• Estimated annual loss of 10,000 tonnes of fish and shrimp catches

1. THE OMVS PROGRAMME

(4 of 4)

1.2. Initial Impacts of Diama and Manantatli Dams on the SRV Floodplain -- Inland Floodplain of the

Middle Valley

• Traditional production systems associated to natural floods

1. THE OMVS PROGRAMME

(4 of 4)

1.2. Initial Impacts of Diama and Manantatli Dams on the SRV Floodplain -- Inland Floodplain of the

Middle Valley

• Alteration of flow regime disorganise waalo production systems

• Affects the ecology of the floodplain, with negative impacts on the flora (case of the Acacia nilotica) and fauna (case of fisheries)

• Double flood peaks damages recession agriculture activities (1991)

• Filling of reservoir results in a « No flood » year (1990) with catastrophic consequences on the living conditions of riparian communities

2. OMVS’ INITIAL REACTIONS

(1 of 2)

• Suggested compensation for lack of flood:

– 50,000 ha of recession agriculture yields

20,000 t of sorghum (at 400kg/ha)

– 5,000 ha or off-season irrigation yields 20,000 t of paddy rice (at 4 tons/ha)

• One weaknesses on the proposed solution:

– It ignores many of the other socio-economic activities dependent on the annual flood (fishing, animal rearing, ecological benefits, etc..)

2. OMVS’ INITIAL REACTIONS

(2 of 2)

• Another weakness:

All households involved in recession ag. do not have access to irrigation (Chart)

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Reach A Reach B Reach C Reach D Reach E reach F

Upper Reaches to Lower Reaches

Reach G

Access to Recession Agriculture Access to Irrigation schemes

Reach H Reach I

3. REALISING THE MAGNITUDE OF

BENEFITS OF ANNUAL FLOODS

• Studies on wetlands benefits, especially in the Hadejia

Nuguru Wetlands (Northern Nigeria)

• SRBMA Studies in 1988-92

– Recession sorghum agriculture with minimal capital and labor investments

– Fisheries benefits

( avg 70 kg/ha )

– Increased livestock carrying capacity of the floodplain

( 0.35

TLU/ha )

– groundwater recharge with benefits on household water supply and on gardening activities

– Forestry benefits (

Acacia nilotica )

In terms of net benefits per unit of land, labour and capital, the floodplain of the Senegal middle valley, if adequately supplied with water, competes favourably with irrigation

4. Constraints to implementing « Environmental

Flows » in the SRV

(1 of 4)

• The notion of EFR is defined as the amount of water that needs to be left in the river system (after withdrawals of diverse uses), or the amount of water that needs to be returned to the river (through releases from dams or through inter-basin transfers) in order to meets specific objectives related to the condition of the river ecosystem (Adapted from King, Tharme and Brown,

1999)

• EFR is also defined as « The water regime provided within a river, wetland or coastal zone to maintain ecosystems and their benefits where there are competing water uses and where flows are regulated » (Dyson, Bergkamp,

Scanlon, 2003)

• EFR « takes cognisance of the need for natural flow variability and addresses social and economic as well as biophysical one » (Davis, Hirji, 2003)

• The debate on EFR has therefore started in the SRV long before the concept gained currency in sustainable development discourse related to water

• In the SRV context, increasing awareness of decision-makers of the benefits of annual flood has been an initial step now largely accomplished

• Operating the dams in order to mimic the natural flooding condition is another thing still not achieved on a sustainable basis due to a number of

CONSTRAINTS

4. Constraints to implementing « Environmental

Flows » in the SRV

(2 of 4)

•

The Economic constraints:

A study commissioned by OMVS on the Optimisation of the benefits from investments made (Study dated 1987) warned that the generation of artificial floods from the Manantali Dam in order to make available

50,000 ha of recession agriculture would result in a loss of 171 GWh/year of power production, then valued at 3.591 billion CFAF

The question was then:

Can the benefits generated by the « artificial flood » compensate the forgone electricity production?

The answer was « NO » as long as the only function of the annual flood was considered to be limited to recession agriculture

The answer became « YES » when other benefits taken into consideration: fisheries, livestock production in particular

Despite this, many still express doubts that its makes economic sense to pursue flood releases from Mananatali Dam

4. Constraints to implementing « Environmental

Flows » in the SRV

(3 of 4)

• Geopolitical Constraints:

Political constraints associated to the transboundary nature of the

SRV: Diverging interests of riparian countries

Country

Guinea

Mali

Mauritania

Senegal

Power Production Irrigation

Potentially high

High

Very High

Très haute

None

Low

Very High

Very High

Navigation

None

Very Hgh

High

High

Recession

Agriculture

None

Low

High

High

•

Constraints related to Power imbalances among stakeholders:

Voices of the rural poor vs voices of the influential urban dwellers and industrial sector

Voices for development (irrigation, electricity, navigation, water supply) vs Voices for nature conservation

4. Constraints to implementing « Environmental

Flows » in the SRV

(4 of 4)

•

Technical constraints

• True that the Manantali Dam is equipped with proper sluice gates to generate artificial floods

BUT

Manantali only controls 40 to 60 of the annual river discharge, hence the difficulty of synchronising controlled and uncontrolled flow to mimic natural flow regime

From Manantali, difficulty to generate a flow regime at the basin level that will address the needs of all water users

Too few knowledge on EFR

Too few information on the hydrology and ecosystem water needs in the SRV and in SSA in general

Limited human capacity to push forward the EFR agenda in SSA

5. Way forward

– Positive Signals from OMVS

•

Opportunity created by the Water Charter

Guinea is as a riparian country is signatory of the Charter

ARTICLE 4 of the Charter: One of the guiding principles for water allocation is the need to protect the environment

ARTICLE 5, subsection on IWRM: Affirm that in allocating available water, the necessary hydraulic conditions should be created for the flooding of the river valley and for supporting traditional recession agriculture

•

Opportunity created by the establishment of the Observatory of the Environment

•

Opportunity that OMVS has increasingly moved toward

“regulatory” functions

5. Way forward

– The Diawling Experience

(1 of 2)

The restoration of the Diawling Floodplain shows that EFR is possible even in data poor context (IK; trial and error; etc..).

What was done?

valuing local knowledge , especially on the pre-dam hydrology and its ecological and socio-economic dimensions

coupling “scientific” investigations with extensive consultations with all relevant stakeholders : fishermen, gatherers of forest products, herders, etc.

Formulating a management plan (1996)

Improving existing small infrastructures built by OMVS as a part of the implementation of the recommendations of the EIA

building of additional embankments and sluice gates for improved inundation of the floodplain

5. Way forward

– The Diawling Experience

(2 of 2)

Conducting artificial flood releases largely on the basis of a trial-and error approach:

• First experimental releases took place in 1995

• Computer-based simulation of flood scenarios and their impacts on the ecosystem and associated activities were only done at a later stage

• Once the flood scenarios were defined, stakeholder consultations and debates took place on the advantages and disadvantages of the various scenarios

• Broad agreement on win-win flood management options (or compromise scenarios) resulted from these stakeholder consultations and negotiations

Results of the Restoration of the Diawling Floodplain

• Fish and shrimp populations have now dramatically increased.

• Groundwater recharge have improved, which boots gardening activities

• Women have resumed their traditional mat weaving activities , using sticks of Sporobolus robustus ] et the fruits of Acacia nilotica

these species having regenerated thanks to improved re-inundation of the floodplain

• The Diawling National Park has become a zone of seasonal transit for thousands of migratory birds .

Year

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

-

Maximum flood extent (ha)

-

15020

16240

10100

20320

27050

Fish catches (kg)

<1000

<1000

10000

15000

10800

25500

74500

Waterbirds (units counted)

2216

5292

66100

32300

14400

40900

35098

1999

2000

29890

32390

113800

No data

38413

No data

Table: Maximum flood extent, amount of fish catches and number waterbirds in the right bank of the Lower Senegal River Source. Hamerlynck et al. 2003

1200

1000

800

600

400

200

0

1994 1995 1996

Flood extent

1997

Fish catches

1998 1999

Birds counted

2000

Fig: Flood extent, Fish catches and population of waterbirds in the Diawling area.

Adapted from: Hamerlynck et al. 2003

5. Way forward

– The GEF SRV Project

The GEF Project for the management of water and environmental resources of the SRV aims to create a participatory environment at the entire basin level (including

Guinea) that enables transboundary cooperation for the sustainable management of the resources of the SRV

The Public Participation Component of the GEF Project

• Identifying the needs and perspectives of water users

• Making the voices of water users, especially the poor farmers, heard and taken into consideration in the CPE deliberations

• Improving awareness of CSO and the general public

• Ensuring mobilisation and involvement of available scientific expertise in basin countries

5. Way forward

– The Project for Improving

Floodplain Productivity

Rationale is to seize current window of opportunity where there is limited competition between irrigation and navigation on the one hand and annual flood releases on the other hand

The Project goal is to improve the conditions of the inundation of selected « cuvettes » in the floodplain, with the objectives of:

• Limiting or correcting the imperfections related to artificial releases from

Manantali (double peaks, etc..)

• Optimising the duration and timing of flooding taking into consideration the needs of the ecosystems and flood-dependent economic activities

• Collecting data to be used in the negotiation for and against the flood

6. LESSONS LEARNED

Lesson 1.

A free flowing river generally has benefits attached to it, and it is a mistake to assume the opportunity costs of altering the natural flow of a river to be zero.

• By comparing and balancing the total impacts

(positive and negative) of the OMVS Programme on the right bank of the lower Senegal River, it is difficult to determine if local communities really benefited from the venture or were net losers. In any case, it seems evident that the benefits of the free flowing river were neglected.

6. LESSONS LEARNED

Lesson 2.

Even if there exist a political will, it is technically a real challenge to conceive and implement flow regimes that respond to the needs and priorities of all water users at the river basin level

From any flow regime scenario implemented at the basin level they will losers and gainers. These imbalances and risks of inequity can be attenuated by managing the waters at the local sub-basin level

(eg. Diawling Floodplain)

6. LESSONS LEARNED

Lesson 3.

In contexts of limited data availability as is often the case in Africa

(data on the hydrology or responses of ecosystems to varying flood patterns), local people’s knowledge can be an excellent source of information for determining empirically ecosystem water needs.

Lack of hydrological data should not be therefore an excuse for not developing and implementing

“environmental flows”.

6. LESSONS LEARNED

Lesson 4.

Ecosystem restoration is a long-term effort and socio-economic benefits attached to it take time to materialise.

In this context it is real challenge to combat poverty through ecosystem management: poor people often require short-term solutions to their survival needs. IUCN addressed this challenge by promoting income-generating activities

(horticulture, employment in project activities like construction works of project offices and of embankments, etc…) while working on the restoration of the Diawling ecosystem

6. LESSONS LEARNED

Lesson 5.

Ecosystem needs (restoration of pre-dam flow patterns) are often synchronised with the needs of poor people whose livelihoods are largely based on flood-dependent activities such as fishing, gathering wild products, livestock rearing, etc…

On the basis of this, there exists opportunities for building a coalition between environmental advocates and local communities.

6. LESSONS LEARNED

Lesson 6.

Given the diversity of benefits generated by ecosystems when properly managed, the question is whether we should not be concerned more by generating more values per drop.

This means that in the allocation of available water priority should be given to uses that generate per each drop allocated more benefits and values at the lowest economic, social and environmental costs. Under this paradigm shift ecosystems compete more favourably with other sectors such as agriculture, hydropower production, etc.

6. LESSONS LEARNED

Lesson 7.

In Africa, the majority of the population, especially the poor, largely rely on the exploitation of highly waterdependent natural resources (traditional agriculture, fisheries, livestock rearing, exploitation of forest products).

In this context there is need to better explore the opportunities of contributing to MDG (poverty reduction, access to safe water, etc.) through ecosystem restoration and enhancement.