How to measure ethnic group diversity and *segregation'

advertisement

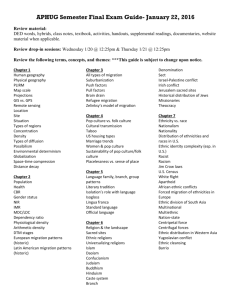

Decreasing segregation and increasing integration in England and Wales: what evidence of ‘White flight’? Dr Gemma Catney Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellow Department of Geography and Planning, School of Environmental Sciences Email g.catney@liverpool.ac.uk Twitter @gemmacatney ‘Diversity and the White working class’ symposium, Birkbeck, 3rd April 2013 • The population of England and Wales has become more diverse, and more mixed. • The White British population remains the majority population, at over 80%. • British national identity is commonly expressed. • Increases in people identifying with a mixed ethnic group, and growth in number of mixed ethnicity households (e.g. partnerships, between generations) and indicator of intimate mixing and integration and greater societal tolerance. How has residential segregation changed? • Segregation decreased in England and Wales between 1991 and 2001(Simpson, 2007); Peach (2009) showed that Britain does not have ‘ghettoes’. • National level 2011 Census data have shown that segregation has continued to decrease since 2001, but at a more accelerated pace (Simpson 2012) • What about segregation at the neighbourhood level? • Index of Dissimilarity: the extent to which an ethnic group’s population is spread across neighbourhoods: 0% indicates a completely even spread of the population within that district, and 100% means complete separation. • Neighbourhood residential integration is increasing: segregation has decreased within most local authority districts of England and Wales, for all ethnic minority groups. • There has been increased residential mixing in major urban centres like Leicester, Birmingham, Manchester and Bradford, for most ethnic groups. London no exception. • The most diverse local areas (electoral wards) are located in districts which have seen a decrease in segregation for the majority of ethnic minority groups. England and Wales, 2001-2011 Output areas within local authority districts Districts with >200 pop. each ethnic group % of districts % change in segregation, 2001-2011 Mechanisms of change in segregation • Decreases for the minority groups: • Migration within England and Wales, away from areas of initial immigrant settlement: • Migration to suburban/rural areas by families with developing housing needs (larger housing, a garden, etc), or attracted by the quieter lifestyle • Suburbanisation and counterurbanisation has been taking place in the UK for several decades • These housing aspirations are not specific to one ethnic group • Greater dispersal within one’s existing residential locale • Greater confidence to move to new areas and greater tolerance in society • Improved knowledge of housing availability, improved opportunities • Immigration to new areas • Increase for the White British? • The White British continue to have low levels of segregation • Increases in neighbourhood segregation are small in most districts (<5% in many) • A function of increased residential mixing: greater sharing of residential environments in previously ‘homogenous’ areas • Segregation for the White ‘group’ taken as a ‘whole’ goes down for neighbourhoods The White British in 2011 • White British less isolated in 2011 than in 2001 (increase in index of exposure) • White British population has remained by far the largest group in England and Wales, but has been in decline in the 2000s: • internal migration to elsewhere in the country; • emigration to a different country • more deaths than births (an ageing population) • Classification of areas into urban/rural typologies show: • There has been a White British population loss everywhere – in London, and in the rest of England and Wales. White British population loss is highest in outer and inner London respectively. • All area types are gaining ethnic minority population, except for population loss in all area types by the White Irish, from inner London for the Caribbean ethnic group, and population loss in some area types for the Any Other ethnic group (although incomparable between time points). • If we look at the % change for each group in an area type (e.g. % people in inner London who identify as White British expressed as the number of people in inner London in 2011 minus the number in 2001, divided by the White British population in inner London in 2011) we see: • For many ethnic minority groups, that group’s smallest gains are in the areas where the White British have seen their greatest population loss. • e.g., there has been a decrease in the percentage of people in inner London who identify as White British; for most other ethnic groups, there has been an increase in inner London by this measure, but it has been smaller than their increases in other areas. ‘White flight’? We have seen there are population gains in some areas, and losses in others, for the White British and ethnic minority groups. Thus, looking at the share of ethnic group populations in area types is a useful way of standardising the data to understand better what’s going on. A decreased share of the total White British population in ethnically diverse urban areas, and their increased share in areas where ethnic minority group populations are lowest may suggest ‘White flight’ IF this is a White British trend, and not mirrored by other ethnic groups. Is this happening? Which area types are ethnic groups decreasing or increasing their share? 6% of the White British in outer London districts in 01; 5% in 11 = 1% decrease in share Summary • It is not possible to assess how far these changes in the shares are due to internal migration, the balance of immigration and emigration, and natural change, however the data do not suggest that there has been a ‘selfsegregation’ of any ethnic group, including White British. • Supported by neighbourhood segregation results • The diversification of ethnic minority groups into areas where they were not previously present suggests new migration streams, for example through suburbanisation or rural in-migration, rather than in situ growth. • London’s younger population = more births and immigration? • Outside London = internal migration? • Cascades of post-immigration and 2nd/3rd generation movement: actually more compelling than we might expect given that these processes take time! (e.g. African group) • Previous research has shown an ‘affluent flight’ rather than ethnic group-specific flight: common migration patterns for all groups. Suburbanisation, rural in-migration, gentrification. • No data on internal migration means we must be careful in asserting ‘White flight’. • What about policy? • If ‘White flight’ were to be taking place? • Not a large social phenomenon; too much attention compared to other pertinent issues! Deprivation, inequalities in housing and employment, discrimination, etc. • Need to better inform local people in local areas about the facts on immigration, diversity and integration • Our increasing diversity is being well-accommodated; going handin-hand with increased integration Decreasing segregation and increasing integration in England and Wales: what evidence of ‘White flight’? Dr Gemma Catney Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellow Department of Geography and Planning, School of Environmental Sciences Email g.catney@liverpool.ac.uk Twitter @gemmacatney ‘Diversity and the White working class’ symposium, Birkbeck, 3rd April 2013 Processes of changing segregation Hypothetical scenarios (a) (c) (b) (d) Cascade of urban-suburban-rural migration Decreased urban segregation; a temporary increased rural segregation