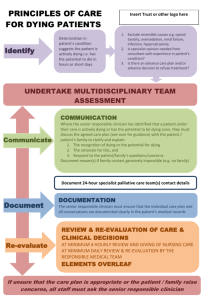

Te Ara Whakapiri: Principles and guidance for

advertisement