main exposition

advertisement

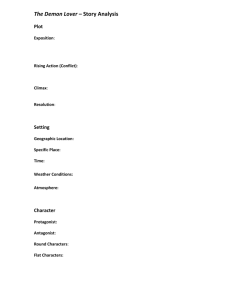

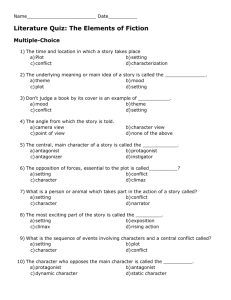

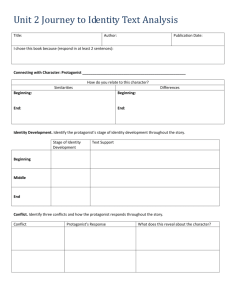

Lecture 8: How do I Fade In? Inside Man (2006) Written by Russell Gewirtz Professor Michael Green 1 Previous Lesson • Plotting – The Twists and Turns • The Role of Conflict • The Principles of Action • Writing Exercise #6 The Philadelphia Story (1940) Written by Phillip Barry (play) and Donald Ogden Stewart (screenplay) In this Lesson • The Problem and Main Exposition • Opening the Movie • Writing Exercise #7 The Apartment (1960) Written by Billy Wilder and I.A.L Diamond The Problem and Main Exposition The Insider (1999) Written by Marie Brenner (article) and Michael Mann & Eric Roth (screenplay) Lesson 8: Part I 4 Writing the Opening • Finding the best opening for a movie can be frustrating since it must: – Be visual – Convey important information – Be interesting if not arresting – Raise questions – Open up a world at least slightly different than our own 5 Writing the Opening (Continued) • It’s problematic deciding how much exposition is necessary and when and how to convey it. • Every word, image and scene must advance the story towards its conclusion. • Because of the abridged time, this is particularly challenging in a short film. • Make sure you understand your story well enough - what you want to have happen before you try to write your opening. 6 The Problem • In writing a terrific opening, you need to start with a problem. • Every great film revolves around a problem for the protagonist and other characters. Consider a few of the short stories we’ve watched so far: – George Lucas in Love – Ten Minutes – Black Button – The Powder Keg – Copy 7 Problem and Theme • In great films, short or long, the problem doesn’t just define the action, but the theme. • It’s incredibly important to understand this but young writers often avoid the opening problem and the story is crippled. • Remember, to take the time to discover what your film is really about before you write. 8 Problem and Conflict • To create unified action the audience can follow, you must know what the main conflict is. • Other problems can exist in the film, but if you have several problems of equal importance, your audience won’t know where to focus. • The main conflict needs to be apparent, and if there are other conflicts, they should play a subsidiary role. 9 Externalizing Conflict • A poor opening often results when the writer uses the protagonist’s inner conflicts as the driving force without knowing how to externalize them. • You need to find the true underlying internal problem facing your character, and find a way to illustrate and foreshadow this problem in the action so that the audience can understand the meaning of the conflict. 10 The Main Exposition • We’ve defined the main exposition as whatever is primary and vital for the audience to know about the protagonist and her problem. • Despite our emphasis on action and showing in film, exposition in a short film often needs to be revealed in other ways because of time. Dramatizing the main exposition in a short film takes too long. 11 Don’t Tell to Much • • • A great short opens as close to the introduction of the main conflict as possible to grab the audience’s attention. But don’t lessen the tension by trying to cram in too much exposition about your protagonist before starting the story - this will kill the story before it begins. It is the purpose of the entire film and screenplay to show us the character. At the beginning all we need is a hint. 12 Purpose of Main Exposition • The main exposition: – Defines setting and tone - humor, fear, etc. – Introduces the main characters and their central relationships – Presents or initiates the conflict – Makes clear whatever is not self-explanatory, but necessary to understand • The main exposition needs to come early and fast to orient the audience. Other details can be spread throughout the film. 13 Handling the Main Exposition • Main exposition can be various. • A Greek Chorus is a classical method directly communicating the background of the plot to the audience. • Shakespeare used prologues, soliloquies. • These techniques and others like them are outdated, but filmmakers, especially those making short films, need the same kind of immediate exposition. 14 Example Henry V (1989) Written by William Shakespeare (play) and Kenneth Branagh (adaptation) Narration • Voice-over narration and even onscreen narrators are more common in short films than features - and more accepted. With voice-over, a narrator can express the necessary information quickly and directly. • Read the example in chapter six from Ray’s Male Heterosexual Dance Hall. • Pause the lecture, go back to Learning Tasks and watch the clip from Apocalypse Now. 16 Written Presentation • Written presentation is also acceptable in a short film - particularly a comedy. • Written presentation immediately makes your viewer an active participant in your work. • The audience must sit up and read what is being show on screen. It makes them pay immediate attention to what is going on, rather than allowing them to sit back and wait for the film to engage them. 17 Example • Pause the lecture, go back to Learning Tasks, and watch the clip from Blade Runner. Blade Runner (1982) Written by Phillip K. Dick (novel) and Hampton Fancher and David Peoples (screenplay) Visual Dramatization • Visual dramatization is the main exposition presented in the form of visuals and action. • Read the section in chapter six in which Cowgill discusses how visual dramatization is used in the short films Occurrence at Owl Creek and The Lunch Date. 19 Exposition in Dialogue • Many films use scenes with dialogue to convey part of the main exposition. As in life, sometimes words are the best way to express what needs to be told. • Pause the lecture, go back to Learning Tasks, and watch the opening scene from Cameron Crowe’s Say Anything. 20 Exposition, Climax and Theme • The main exposition has a direct relationship to the film’s climax as well as one with the film’s theme, because the problem posed a the beginning of the story is one that needs to be solved or answered at the end. • Theme also needs to be foreshadowed or revealed at the start. The audience is going to grasp the film’s intent only if the theme is introduced early. 21 Exposition, Climax and Theme (Continued) • You don’t have to directly tell viewers what a film is about, but they need hints, clues. If every viewer has a different interpretation, the theme hasn’t been well-developed. • Exposition, particularly in dialogue, continues without interruption until the climax of the movie, since we are always revealing characters, plot and backstory. 22 Questions to Consider • When working on the main exposition, ask yourself these questions. – What is essential to be revealed? – What can be held back? – What can be implied? • Holding back or implying certain information can help you to maintain tension and make the audience anticipate what will happen next. If you reveal too much, there is no suspense or surprise. 23 The Problem and the Sub-Problem • Think of your main conflict as a question that will be answered at the climax. • However, beyond the main conflict, most films develop other conflicts or problems for the protagonist to face. • Sometimes these are just additional obstacles or complications, but some films weave sub-problems into the plot and develop them along with the main problem. 24 The Problem and the SubProblem (Continued) • The sub-problem may concern the protagonist, antagonist or another character who indirectly affects the protagonist. • These are conflicts of secondary importance that impact the plot. In concept they resemble subplots. Both give dimension to a story, add tension and increase the level of audience involvement. • In short films, subplots can frame the main 25 action or be involved with it. Opening the Movie The Sea Inside (2002) Written by Alejandro Amenábar and Mateo Gil Lesson 8: Part II 26 Point of Decision • Great shorts open near a point of decision or crisis, and the more dramatic, the better. Out of a life-changing situation, the protagonist’s goal emerges. Life-changing events include: – Starting school – Graduating school – Birth – Wedding – Losing or quitting a job – Divorce 27 Change in the Environment • Another strategy for starting a film may begin with a change in the environment that affects the protagonist directly or indirectly, such as war, natural disaster, or a death in the family. 28 The Protagonist • Many films open by introducing the protagonist - showing us up front what is important, interesting or unique about her. • Ask what is essential for the audience to initially know about this character. • You might illustrate the outer façade first, so that her inner essence might later be illustrated through conflict. The Protagonist (Continued) • Consider how you want to present your protagonist to the audience. – Should we laugh at her or pity her? – Should we take him seriously or not? – Should we identify with the protagonist? • These questions relate to the tone of the film - whether it is satiric, broadly humorous, serious or ironic. • How the audience feels about the character depends on how you do. Opening Scene Considerations • First, does the opening scene raise a question about what will happen in the story? If not, when will it come? • Second, is there action or conflict in the scene to make it interesting? What does the character want to achieve in the scene? • Third, what can we learn in the opening that we can utilize in the end? The earlier we see a detail about a character that affects the outcome, the less contrived it feels. Assignments Ordinary People (1980) Written by Judith Guest (novel) and Alvin Sargent (screenplay) Lesson 8: Part III 32 E-Board Post #1 • Watch the short film from the lesson, Spin, and analyze the film’s opening. How does it utilize concepts from the lesson in creating the problem, main exposition, protagonist, and so on? You may need to return to the lecture or the book to brush up on the concepts. 33 E-Board Post #2 • Choose any feature film you have seen and discuss how the opening is related to the climax of the film. What bits of story and character information return from the beginning to have an impact at the end? 34 Writing Exercise #7 • Now that you have your treatment completed and have written a scene in screenplay format, write the opening scene of your script. Make sure that the scene is in proper screenplay format and that it follows the basic plan for creating an opening that we studied in this lesson. 35 End of Lecture 8 Next Lecture: How do I Keep My Story Alive?