The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot Developed

advertisement

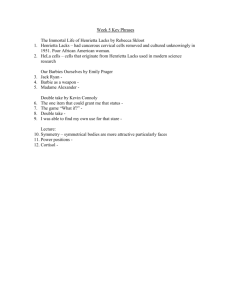

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot Developed by Darlene Stotler Student Version Reading Selections for This Module Skloot, Rebecca. The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. New York: Broadway Books-Random House, 2011. Print. Reading Rhetorically Prereading Activity 1 Getting Ready to Read This first Quickwrite activity will enable you to make the human connection between the woman, Henrietta Lacks, and the scientific realm that her cells have been impacting for the past six decades. First, log onto http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/Henrietta-LacksImmortal-Cells.html, and view the site. From this Internet site, you can get an overview of the origins of Henrietta Lacks and her ultimate immortality generated by harvesting tissue and cells from her body. Turn to page 206 of the text, begin looking at the photographs that follow, and then respond to the following questions. Be sure to write in complete sentences. 1. What do these different photographs reveal about Henrietta’s family? 2. Look at the pictures of the cells. These photographed cells are from a woman who has been dead for more than sixty years. What do you think of this indestructible cell line and the fact that Lacks’s cell lines have been able to help cure polio, assist in AIDS research, and help cure numerous other diseases? Activity 2 Exploring Key Concepts The following quote is from The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. Read the quote as stated by Sonny Lacks, Henrietta’s middle son, and focus upon the gravity of this situation. Then, contemplate what the author, Rebecca Skloot, is conveying to her audience through Sonny’s remarks. After reading the quote, answer the questions that follow. Strive to find your own writer’s “voice” by taking a particular stance about this ethical, and tragic, situation that Sonny is addressing: “John (sic) Hopkin (sic) didn’t give us no information about anything. That was the bad part. Not the sad part, but the bad part, cause I don’t know if they didn’t give information because they was making money out of it, or if they was just wanting to keep us in the dark about it. I think they made money out of it, cause they were selling her cells all over the world and shipping them for dollars.” “Hopkins say they gave them cells away,” Lawrence yelled, “but they made millions! It’s not fair! She’s the most important person in the world and her family living in poverty. If our mother so important to science, why can’t we get health insurance?” (168) What kind of emotion is Sonny expressing towards Johns Hopkins Hospital? Do you believe Sonny’s emotions are justified or is he overreacting? Sonny states the way the hospital treated Henrietta was the bad part. What is the “sad part” that Sonny is alluding to, and what makes this aspect of Henrietta’s life so tragic? Activity 3 Activity 4 Surveying the Text Write down five interesting facts about the author, Rebecca Skloot. Where and when was this book published? By what publisher? Go to the beginning of each chapter. Note the graphic that introduces each chapter and its prominent placement above the chapter title. Describe the graphic and its significance. Flip through the various chapters. What significant literary device is being used among the timelines? Why do you think Skloot chose this? Making Predictions and Asking Questions Based on the results of surveying the text, answer the following questions: 1. What do you think this text is going to be about? 2. What do you think is the purpose of this text? 3. Who is the intended audience for this piece? 4. Look at Skloot’s title, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. What do you think her work will be about? Share your inferences with a partner or in a small group. After you discuss what you think the book will be about, study the cover photograph of Henrietta Lacks. Jot down a few notes about her physicality and any other ideas you might formulate as you are viewing the cover photo. Turn to the “Prologue,” and read the three paragraphs up to these words: “Her real name is Henrietta Lacks.” What do you think Skloot is trying to reveal about the life of Henrietta Lacks? Now, read the rest of the Prologue (pages 2-7), and answer the following questions: 1. What kind of person is the author? 2. What do you think the author wants us to learn from her book? 3. Do you think you can learn something from this book that can be applied to your life? Why or why not? Activity 5 Understanding Key Vocabulary This book contains numerous medical and scientific words that will enable readers to become more cognizant of a cell’s growth and the subsequent discoveries made via the HeLa cells. Skloot employs an ambitious variety of academic and scientific diction that strengthens vocabulary skills. Working in groups, complete the following chart for each of the words, terms, or concepts listed. Be prepared to discuss the findings with the class. Word & Etymology hypothesis Nuremberg Trials Nuremberg Code zeal cavalier DNA genome virulent telomeres Jim Crow Laws statute of limitations cytoplasm Dictionary* Definition (*Encyclopedia for person’s name) Your Definition Use the Word in a Sentence Explain the Significance of the Word carcinoma in situ malignant fait accompli metastasize petri dish formaldehyde pathology Jonas Salk polio spontaneous transformation replicate cloning chromosomes Down syndrome Klinefelter syndrome Turner syndrome nodules prognosis Hippocratic Oath informed consent immoral deplorable Parkinson’s disease Yiddish fallacious somatic cell fusion centaurs Koran genetic marker adenocarcinoma bioengineering antibodies Actin filaments mitochondria Gold Digger Reading Activity 6 Reading for Understanding The following textual quotes address ethical issues that can prompt dialogue and could be included in the postering session: “‘In the setting in which the patient is involved in an experimental effort, the judgment of the investigator is not sufficient as a basis for reaching a conclusion concerning the ethical and moral set of questions in that relationship.’” (Skloot 135) “Later that year, a Harvard anesthesiologist named Henry Beecher published a study in the New England Journal of Medicine showing that Southam’s research was one of hundreds of similarly unethical studies. Beecher published a detailed list of the twenty-two worst offenders, including researchers who’d injected children with hepatitis and others who’d poisoned patients under anesthesia using carbon dioxide.” (135-136) “Despite scientists’ fears, the ethical crackdown didn’t slow scientific progress. In fact, research flourished. And much of it involved HeLa” (136). “‘The [Lacks] family has suffered greatly . . . This family is, like so many others today, attempting to grapple with the many questions and the moral and ethical issues that surround the ‘birth’ of HeLa, and the ‘death’ of Mrs. Lacks . . . The questions of (1) whether or not permission was received from the ‘donor’ or her family for either the ‘use’ of HeLa worldwide or the ‘mass,’ and commercial, production, distribution, and marketing of Mrs. Lacks’ cells . . .’” (224) “The difference between Ted Slavin, John Moore, and Henrietta Lacks was that someone told Slavin his tissues were special and that scientists would want to use them in research, so he was able to control his tissues by establishing his terms before anything left his body. In other words, he was informed, and he gave consent. In the end, the question is how much science should be obligated (ethically and legally) to put people in the position to do the same as Slavin.” (326) Activity 7A Mapping the Organizational Structure The chapter entitled “The HeLa Factory” found on page 93 contains a definitive chronological structure that fosters a tone of urgency and of paramount importance. Draw a line where the chapter’s introduction ends and annotate in the left margin the word “introduction.” Highlight in yellow the thesis, or main idea, of the introduction. Label in the left margin the word “thesis.” Finally, draw a line beneath three or four key premises (supporting points) that further advance and support the thesis in the introductory paragraph. Label in the left margin the word “premise.” After you have drawn the lines within the text, discuss these questions either as a class or in separate groups: 1. Where did you locate the end of the chapter introduction? How did you decide this was the introduction’s ending? 2. What is the thesis statement in the introductory paragraph? 3. What premises, or sentences that support the thesis, did you find? 4. How does Skloot’s use of chronology affect the overall tone of this chapter? Activity 7B Descriptive Outlining Draw a vertical line down the middle of your notebook paper. Across the top, draw a horizontal line. Label the top left column “Content: What Skloot Is Saying,” and at the top right column, write “Rhetorical Purpose: Why Skloot Put It There.” The left column will contain the words exactly from the text. In the right column, you will state why you think Skloot used the kinds of words that she did. Content: What Skloot Is Saying Rhetorical Purpose: Why Skloot Put It There At the end of the chapter, describe the overall content and purpose. After this has been done, you may want to ask the following kinds of questions: Activity 7C What does each paragraph say? What is its content? How does each paragraph affect the reader? What is the writer trying to accomplish? Which paragraph is the most developed? Which paragraph is the least developed? On the basis of your descriptive outline of “The HeLa Factory” chapter, what do you think is the main point? Is that point explicit or implicit? Drawing Conclusions from Structure One of the most vital communication skills is the ability to take written text and summarize in your own words a specific text’s original meaning. Taking the chapter entitled “The HeLa Factory” (or a different chapter if you are working as a group and have been assigned another chapter), summarize that chapter in a welldrafted paragraph. In composing a summary, you need to consider the following questions: Activity 8 How did the author order the chapter? (Which event comes first, in the middle, last?) What is the effect of this order on the reader? How has the structure of the chapter helped make the author’s premise clear, convincing, and engaging? Noticing Language Here are some health industry and scientific words and phrases from the text that may or may not be unfamiliar to you. Some of these words you may have seen before while others may seem new. The best method to identify the meanings of the words is to consult the Index at the back of the text that begins on page 367. culture culture medium American Type Culture Collection Standardization of the Field FISH The HeLa Cancer Control Symposium HLA Marker Medical Genetics National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis Tuskegee Syphilis Study Activity 9 Annotating and Questioning the Text Turn to page 275 in Chapter 33 entitled, “The Hospital for the Negro Insane.” This activity works best with small learning groups. Follow directions listed below. 1. Label these elements in the left-hand margin next to the following sentences: Issue or problem being addressed: “The Crownsville that . . .” Author’s examples: “In 1955 . . .” ; “In 1948 . . .” ; “Patients were locked . . .” Conclusion: “As we left Crownsville . . . times was different.” 2. In the right-hand margin, same locations for each element listed above in #1, note your reactions to what the author is saying. Questions about the issue or problem being addressed Reflections on the quality of the evidence or examples Challenges to the author’s inferences or conclusions 3. Finally, write your annotations in the margins. Activity 10 Analyzing Stylistic Choices In order for cells to grow successfully, a cell medium had to be concocted. The imagery, diction, and syntax Skloot uses on page 50 make this vital, scientific research step seem comical. Reading this paragraph either individually or in small groups will enable you to answer the following question: “To what extent does the language of the text support the purpose of the author?” Then identify the imagery, diction, and syntax. Turn to page 50 and read the opening paragraph that begins, “The other ingredients weren’t so easy . . .” and ends with “ . . . so Margaret could fry it for dinner” (Skloot 50). Then, using four felt markers, follow the instructions below. Highlight the compound sentences in yellow. Highlight the complex sentences in pink. Highlight the compound-complex sentences in orange. Highlight individual words that lend themselves to vivid imagery in blue. Once the highlighting is complete, write a few sentences in your notebook of why this particular passage, with its choice of imagery, diction, and syntax, helps fulfill Skloot’s purpose of detailing the origins of HeLa. Postreading Activity 11A Summarizing Taking the annotations from the left-hand margins of the text on page 277, construct a summary using your knowledge of the author’s content and structure. Be sure your summary is centered on this chapter’s main idea. After you have written your summary, highlight the chapter’s main idea. Activity 11B Responding In reference to Chapter 33, write down on 3” by 5” index cards open-ended questions that focus on Deborah’s feelings about discovering Elsie’s photo and medical records. Then, submit your cards to your teacher, who will read a few select questions to the class so discussion can be initiated. Activity 12 Thinking Critically Questions about Logic (Logos) 1. What is Skloot’s major theme and assertion made in this reading? Do you agree with the author’s main ideas? 2. What evidence has the author supplied to support her claim? How relevant and valid do you think the evidence is? 3. How has the author developed her ideas over the course of the text? Questions about the Writer (Ethos) 4. What can you infer about the author from the text? 5. Does this author have the appropriate background to speak with authority on this subject? Questions about Emotions (Pathos) 6. Does this piece affect you emotionally? Which parts? 7. Do you think the author is trying to manipulate the reader’s emotions? In what ways? At what point? 8. Do your emotions conflict with your logical interpretation of the arguments? 9. Does the author use humor or irony? How does that affect your acceptance of her ideas? Activity 13 Reflecting on Your Reading Process Answer the following questions: 1. What have you learned from joining this conversation? What do you want to learn next? 2. What reading strategies did you use or learn in this module? Which strategies will you use in reading other texts? How will these strategies apply in other classes? 3. In what ways has your ability to read and discuss texts like this one improved? Connecting Reading to Writing Discovering What You Think Activity 14 Considering the Writing Task Determine the rhetorical purpose of your upcoming writing assignment by answering the following questions. Then, after you have answered the questions, go to the prompts. You only have to write about one prompt. Here are the questions that will help guide you before you select one of the prompts: Are you informing or reporting? Are you going to try to persuade your readers of something? What genre is this? Is it a letter, an essay, a report, an email or something else? What format will this have? What are the reader expectations for this genre? What is your rhetorical purpose? What will you try to accomplish in your essay? Now that you have had a chance to familiarize yourself with the kind of essay you are going to write and the basic formatting of it, write an essay addressing one of the following prompts: 1. Skloot poses these questions in her Afterword: “Wasn’t it illegal for doctors to take Henrietta’s cells without her knowledge? Don’t doctors have to tell you when they use your cells in research? ” (316). Do you think the doctors should have been more open with Henrietta regarding the use of her cells? Take a stance either for or against this scenario. You will need to gather evidence that supports your claim and argue your point. 2. Read the following excerpt from the Foreword. Scientists use these samples to develop everything from flu vaccines to penis enlargement products. They put cells in culture dishes and expose them to radiation, drugs, cosmetics, viruses, household chemicals, and biological weapons, and then study their responses. Without those tissues, we would have no tests for diseases like hepatitis and HIV; no vaccines for rabies, smallpox, measles; none of the promising new drugs for leukemia, breast cancer, and colon cancer. And developers of the products that rely on human biological materials would be out billions of dollars. (Skloot 316) Skloot further explains that although a person may have volunteered to donate “tissue scraps” for research, other damaging information concerning a patient’s DNA or medical history could be exposed during this process. If you had the chance (you may have already consented on your driver’s license) to donate tissue and/or blood samples for medical research, would you give your consent? Take only one stance. 3. Visit http://www.henriettalacksfoundation.org. After studying this website, write an essay defending what you believe is the most important aspect of this website. Activity 15 Activity 16 Taking a Stance What is the gist of your argument in one or two sentences? Turn these sentences into a working thesis statement. What would you say is your main claim at this point in time? How do your ideas relate to what others have said? What arguments or ideas are you responding to? What evidence best supports your argument? What evidence might you use in relation to what others say about your argument? How does it support your argument? What background information does the reader need to understand your argument? What will those who disagree with you have to say about your argument? What evidence might they use to refute your ideas? How did your views change during the reading? What factors caused you to change? Could you use these factors to change someone else’s views? Gathering Evidence to Support Your Claims Select evidence to support your argument by returning to the readings, your notes, your summaries, your annotations, your descriptive outlining, and other responses in order to highlight information you may use to support your claims and refute the claims of those who disagree. Reflecting on the following questions will provide an opportunity for you to evaluate your evidence and determine its relevance, specificity, and appropriateness in relation to the rhetorical situation. Activity 17 How closely does each piece of evidence relate to the claim it is supposed to support? Is each piece of evidence a fact or an opinion? Is it an example? Highlight in blue the facts; highlight in pink the opinions. If the evidence is a fact, what kind of fact is it (statistic, experimental result, quotation)? If it is an opinion, what makes the opinion credible? Is the opinion provided by an expert on a specific subject or social concern? What makes this evidence persuasive? Are there irrefutable statistics that have been gathered and reported by credible researchers that have no other conflicting interests other than to report the data? How well will the evidence suit the audience and the rhetorical purpose of the piece? Getting Ready to Write Whole-class discussion: Discuss as a class the best structure for your essay, given what you have discovered about the legal and ethical issues that surround Henrietta Lacks’s cells. Evidence: In small groups, write down the evidence you have in your notes and the annotations in your book. Decide among yourselves which are the most compelling notes and statistics that will give further credence (ethos) in your final essay. Audience: All members of all the groups should discuss and make notes about audience. Who will be reading your essay? Your instructor, of course, but your colleagues also will be reading, and perhaps peer-editing at least one draft of your essay. Writing Rhetorically Entering the Conversation Activity 18 Composing a Draft The most important concern for the first draft is to get your ideas down on paper. Your introduction should contain some main ideas about the book and your thesis statement, the main idea you are addressing and subsequently defending in your essay. Usually, the next section will include some general information about the setting of the book. Other essay elements should include the main person, in this case, Henrietta Lacks, the conflicts and issues surrounding the end of her life, and the subsequent historical research involving her cells. The following paragraphs should discuss the theme of the book and the main points you want to cover from the list you have already made. These points, or premises, should support your thesis statement. Defend your thesis and supporting points with quotations and paraphrases from the text. In the conclusion, pose a new idea a reader might learn from reading the book. Activity 19 Considering Structure 1. To write a thesis statement for an argument essay, you must take a stand for or against an action or an idea. In other words, your thesis statement should be debatable—a statement than can be argued or challenged and will not be met with agreement by everyone who reads it. Your thesis statement should introduce your subject and state your opinion (this is your point of attack, or why you believe the way you do) about your subject. Many thesis statements occur in the first or second paragraph of an essay. Before you formulate your thesis statement, be sure to answer these questions: What support have you found for your thesis? What is your response to the question or problem? (This is your tentative/working thesis.) What support have you found for your thesis? What evidence have you found for this support? For example, facts, statistics, authorities, personal experience, anecdotes, stories, scenarios, and examples. How much background information do your readers need to understand your topic and thesis? If readers were to disagree with your thesis or the validity of your support, what would they say? How would you address their concerns (what would you say to them)? Now, draft a possible thesis for your essay. Once you have written your thesis, highlight in blue the factual portion of your thesis and highlight in pink the opinion portion of your thesis. 2. Find out as much as you can about your audience before you write. Knowing your readers’ background and feelings on your topic will help you choose the best supporting evidence and examples. Suppose you want to convince a culturallydiverse group about medical ethics. You might tell the group members that the major cause of death among youth under the age of 25 involves an accident, and while this is a tragedy, youthful, healthy organs donated to others can save lives. If there are audience members who oppose donating an organ, this would be an excellent opportunity to learn others’ ethics and beliefs regarding organ donor programs. 3. Choose evidence that supports your thesis statement. Evidence is probably the most important factor in writing an argument essay. Without solid evidence, your essay is nothing more than opinion; with evidence, your essay can be powerful and persuasive. If you supply convincing evidence, your readers will not only understand your position, but they may also perhaps agree with it. Evidence can consist of facts, statistics, statements from authorities, and examples or personal stories. Examples and personal stories can be based on your own observations, experiences, and reading, but your opinions are not evidence. Other strategies, such as comparison/contrast, definition, and cause and effect, can be particularly useful in building an argument. Use any combination of evidence and writing strategies that will help you support your thesis statement. 4. Anticipate opposing points of view. In addition to stating and supporting your position, anticipating and responding to opposing views are important. Presenting only your side of the argument leaves half the story untold—the opposition’s half. If you briefly acknowledge that there are opposing arguments and answer them, you will move your reader more in your direction. 5. Find some common ground. Pointing out that common ground between you and your opposition is also an effective strategy. Common ground refers to points of agreement between two opposing positions. For example, one person might believe the donating of organs is a noble act, while another may oppose this belief. But they might find common ground—agreement—by agreeing upon patients’ rights and consent regarding organ and tissue harvesting to further medical research. 6. Maintain a reasonable tone. Just as you probably wouldn’t win an argument by shouting or making mean or nasty comments, don’t expect your readers to respond well to such tactics. Keep the “voice” of your essay calm and sensible. Your readers will be much more open to what you have to say if your arguments are rational and sound. 7. Organize your essay so that it presents your position as effectively as possible. By the conclusion of your essay, you want your audience to agree with you. So you want to organize your essay in such a way that your readers can easily follow your argument. The number of your paragraphs may vary, depending on the nature of your assignment, but the following outline shows the order in which the features of an argument essay are most effective: Outline Introduction Background Information Introduction of subject Thesis Statement Body Paragraphs Common Ground Abundant Evidence (more logical than emotional) Opposing point of view Response to opposing point of view Conclusion Restatement of your position Call for action or agreement The arrangement of your evidence in an argument essay depends to a great extent on your readers’ opinions. Most arguments will be organized from general to particular, from particular to general, or from one extreme to another. When you know that your readers already agree with you, arranging your details from general to particular or from the most to least important is usually most effective. With this order, you build on your readers’ agreement and loyalty as you explain your thinking on the subject. If you suspect that your audience does not agree with you, reverse the organization of your evidence and arrange it from particular to general or from the least to the most important. In this way, you can take your readers step by step through your reasoning in an attempt to get them to agree with you. The following is an effective skeleton outline that would serve well in an argumentative essay format: Introduction Background information about the origins of the HeLa cells Introduction of subject (impact of HeLa cells) Evidence—Examples and statistics of the impact the Henrietta Lacks cells have had upon medical research Evidence—Statement from research specialists Evidence—Amount of dollars bio-engineering firms have earned as a result of the HeLa cells Statement of Opinion: Your thesis statement Body Paragraphs Topic—HeLa cells reproducing since 1951 Evidence—Research labs continuously reproducing and acquiring more HeLa cells and profiting from them; Topic—HeLa cells’ role in eradicating polio, shedding light on the HIV virus, helping cure other diseases Evidence—Statistics that relate directly to the HeLa cells’ development and the illnesses the cells have cured Evidence—Statement from medical and research experts Evidence—Statement from a patient survivor that has benefited from HeLa research Topic—HeLa cells and continuous global sales Evidence—Statements from friends, relatives of deceased Evidence—Statements from lab scientists, economics professionals Common Ground—Remain proactive about scientific research Opposing point of view: Belief that Henrietta Lacks’s family should receive some form of compensation Response to opposition: In 1951, no informed consent laws Response to opposition: Agencies such as the National Institutes of Health making amends with the family of Henrietta Lacks Conclusion: The health industry and necessity of continuous use of HeLa cells vs. recompense for the family of Henrietta Lacks Author’s Opinion: More research is vital Activity 20 Author’s Opinion: Increased dialogue between the NIH and the Lacks Family for survivors’ protection Restatement of Problem: Continuous debate regarding the legal issue involving Henrietta Lacks’s case and the ethics surrounding the massive capital raised from the HeLa cells Using the Words of Others (and Avoiding Plagiarism) In order to effectively present your claims, it is imperative that you bolster your argument by incorporating research. However, the research you select needs to be presented in a variety of ways. There are three standard methods of embedding research into an essay: direct quotation, summary, and paraphrase. The direct quote is taking the text verbatim from the research and enclosing the text in quotation marks. A summary means to take a portion of text and write briefly the main idea of the original text. To paraphrase a segment of original text involves identifying the main ideas; however, the length of a paraphrase is similar to the length of the original text. Note that in either a summary or a paraphrase, you are to write only the main ideas without adding any of your own personal opinions or interpretations. You are to record only the information. The following three examples would work well in conjunction with topic of the sample essay that is being outlined in this module: the historical significance and ethical issues surrounding the cells of Henrietta Lacks. Look closely at the following research. The first example is a direct quote, followed by a summary, and concluding with a paraphrase. As a writer, you will become more adept at incorporating direct quotes, paraphrasing, or summaries within the body of your essay as well as deciding which method will be the most effective within the various parts of your essay. Once you have studied the three methods of recording research, you will be ready to do some independent research. Taking the topic of your essay, find research that reflects your topic. Take one direct quote and write it in all three methods in your notebooks: Direct Quotation, Summary, and Paraphrase. Be sure to consult directions on how to cite your sources. Direct Quotation: “‘In 20 years at NIH, I can’t recall a specific circumstance more charged with scientific, societal and ethical challenges than this one,’” Dr. Francis Collins, NIH director, said in the Los Angeles Times Science Now article “NIH gives Henrietta Lacks’ Immortal Cells New Protections,” by Amina Khan (par. 8). Summary: In the Los Angeles Times Science Now article “NIH Gives Henrietta Lacks’ Immortal Cells New Protections,” by Amina Khan, Dr. Francis Collins, NIH Director states he has never seen a case surrounded by such a spectrum of issues. Paraphrase: In the Los Angeles Times Science Now article “NIH Gives Henrietta Lacks’ Immortal Cells New Protections,” by Amina Khan, Dr. Francis Collins, NIH Director, explains that this instance has created more controversy involving issues of society than any he has ever encountered (par. 8). Learning to cite accurately and determining how best to incorporate the words and ideas of others are essential for you to establish your own ethos. You’ll also want to practice choosing passages to quote, leading into quotations, and responding to them so that they are well-integrated into the body paragraphs of your essay. Activity 21 Negotiating Voices Take one example of a direct quote, one example of a summary, and one example of a paraphrase from the same research topic. For example, if you are devoting a particular body paragraph that covers the ethics surrounding the excising of the original specimen sample of Henrietta Lacks, make sure each piece of research has a direct quote, a summary, or a paraphrase that covers that topic. Begin your body paragraph with a topic sentence introducing the topic of research; then, follow it with one of the three selected methods of research. Next, swirl in your opinion or analysis of the preceding research. Do this with the remaining two examples of research. Your body paragraph will marshal evidence of solid research quoted directly, summarized, or paraphrased, and then complemented by your analysis that supports your thesis. Activity 22 Using Model Language Composing body paragraphs that pull together varied voices from a spectrum of research is a skill that you will use well beyond your time spent in academic writing. One skill that is particularly useful is developing strong and coherent introductory sentences that set up your research. The following template sentences can help you with this vital task of combining the research you have culled into one coherent whole that further advances your argument: The issue of ______ can be viewed from several different perspectives. Experts disagree on what to do about ______. Here are other introductory segments that introduce ideas from particular writers: Noted researcher John Q. Professor argues that . . . In a groundbreaking article, Hermando H. Scientist states that . . . According to Patricia A. Politician . . . And when visiting opposing viewpoints, contrary views can be signaled by adding these transitional phrases: However, the data presented by Hermando H. Scientist shows . . . On the other hand, Terry T. Teacher believes . . . Conversely, Bruce Daniels asserts . . . Once your research has been introduced, you now need to add your voice to the mix: Although some argue for ________, others argue for _______. In my view . . . Though researchers disagree, clearly . . . Revising and Editing Activity 23 Rhetorical Analysis of a Draft Team up in groups of four so that you will have, by the end of this activity, a total of three different opinions of one body paragraph of your essay. Once you are in your group of four, each team member passes his/her essay clockwise to the next team member. Now, take the handout sheet that has the following questions already printed on the handout. Read the following questions so you can perform a rhetorical assessment of your first draft. Be sure to answer the questions in complete sentences in your notebooks: What is the rhetorical situation? Who is the writer’s audience, and what is the writer’s argument? Activity 24 What types of evidence and appeals does this writer’s audience value most highly? How can the writer further establish his/her own authority to address this issue? What credibility does the writer have with his/her audience? What are the most important factors contributing to either the success or failure of the argument? What is the most relevant feedback I can give my colleague about his/her audience and context? Considering Stylistic Choices The skillful use of diction and syntax can enhance the tone of any essay. Most readers respond best to an essay that has chosen words that say exactly what the writer means. Ask yourself these important language questions and make appropriate changes before submitting your final draft: Activity 25 How will the language you have used affect your reader’s response? Which words or synonyms have you repeated? Why? Do the words you have chosen convey exactly what they are meant to say? What figurative language have you used? Why did you use it? What effects will your choices of sentence structure and length have on the reader? In what ways does your language help convey your identity and character as a writer? Is your language appropriate for your intended audience? Editing the Draft You now need to work with the grammar, punctuation, and mechanics of your draft to ensure that your essay will conform to the guidelines of standard written English. Working individually, edit your draft based on the information you have received from your instructor. 1. For the most comprehensive help with grammar, mechanics, etc., consult http://www.purdueonlinewritinglab.com. 2. If possible, set your essay aside for 24 hours before rereading to find errors. 3. If possible, read your essay aloud to a friend so you can hear your errors. 4. Reading your essay backwards will eliminate anticipatory reading and force your eyes to move more slowly across the page as they scan from right to left, thus detecting more errors than conventional left-to-right reading. 5. With the help of your teacher, tutor, or peer reviewer, determine your own pattern of errors—the most serious and frequent errors you make. 6. Look for only one kind of error at a time. Then go back and look for a second kind of error, and, if necessary, a third. 7. Use an online dictionary to check spelling and confirm that you’ve chosen the right word for the context. Activity 26 Responding to Feedback Instructors use a variety of methods when grading essays. Look for the following strategies instructors employ to ensure their students are continually progressing as academic writers: Take your graded essay and on a 3” by 5” notecard write the following terms: Introduction & Hook Thesis Statement Body Paragraph Conclusion Once you have written the terms, go back to each section of your graded essay, and write down your instructor’s comments. Then, following your instructor’s comments, write down what you are going to do to correct/improve this particular portion of the essay. For example, is your thesis weak? Is it lacking a strong point of attack? If you run out of space on your index card, get another card and write the revisions on the second. Activity 27 Minimal Marking Your teacher will have electronically projected onto the front of the classroom the following three questions: What is the best feature of this essay? What is the biggest overall difficulty with this essay? How could I improve this essay? On a sheet of paper, write down these three questions and answer them honestly in relationship to your essay. Keeping your questions and answers, pass your essay to the person behind you. If you are seated in the last seat in your aisle, take your essay up to the person sitting in the front of your aisle. You do not have to rewrite the questions that are projected at the front of the room, but go ahead and write on a sheet of paper the answers to the three questions as they pertain to your colleague’s essay. When finished, return the essay, your answers and comments to your colleague. Activity 28 Acting on Feedback Answer the following questions: Activity 29 What are the main concerns my readers had in reading my draft? Do all of the readers agree? What global changes should I consider (thesis, arguments, evidence, organization)? What do I need to add? What do I need to delete? What sentence-level and stylistic problems do I need to correct? What kinds of grammatical and usage errors do I have? How can I correct them? Reflecting on Your Writing Process Answer the following questions: What have I learned about my writing process? What were some of the most important decisions I made as I wrote this text? In what ways have I become a better writer?