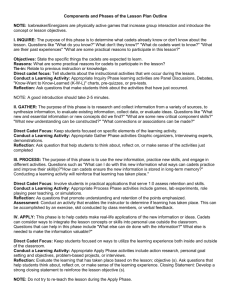

Cadet Forces Instructional Techniques (CFIT) Handbook

CADET FORCES

INSTRUCTIONAL

TECHNIQUES

(CFIT)

INSTRUCTOR

HANDBOOK

FOR THE ACF AND CCF (ARMY SECTIONS)

Sp Comd Cadets Branch TDT

Project No:

Reference

Author

Reviewers

Version History

LAND/RF/1-7-1-1(TDT)

Lt Col G F Moncur

OC TDT

TDT Analyst

TDT WO

Sp Comd Cdts Br Trg WG

Version 0.1

Version 0.2 - 0.4

Version 0.5

Version 0.6 – 1.0

Version 1.1

Date: 25 Feb 13

27 Sep 12

29 Nov 12

25 Feb 13

Initial draft

Peer reviews

Working Group review

Peer reviews

Final

PREFACE

This handbook is intended for use by anyone who instructs cadets or adult volunteers in the Army’s cadet forces or who commands or manages those who do. It should be used as a reference by

CCF officers and, in the ACF, by all those from probationary instructors in training through to commandants. It is designed to also be used by cadet training team and Cadet Training Centre staff, CCF School Staff Instructors, RFCA employed permanent staff and all those who are authorised to instruct the Army’s cadets or who support and work with the Army’s cadet forces.

It supersedes Chapter 1 of the Cadet Training Manual Volume II (Army Code No 71463). It has been published, temporarily, as a standalone document. In due course it will be incorporated into a new training manual for the Army’s cadet forces.

Those individuals who are already qualified teachers, trainers or instructors with up to date instructional experience may instruct cadets in subjects where they are appropriately qualified in accordance with JSP 535 (Cadet Training Safety Precautions - ‘The Red Book’). They are to be deemed competent to instruct by holding a relevant qualification (eg MEd, BEd, PGCE, Cert Ed,

PTTLLS, CTTLLS, DTTLLS, DIT, DITT, SCIC or CCF Leadership Cadre) and evidence of recent instructional experience. They should be approved as competent in the subject they are delivering by the ACF county training officer or CCF contingent commander. Qualified and experienced personnel will already be familiar with much, but possibly not all, of the contents of this handbook.

Throughout this handbook:

The terms “officers”, “adult instructors” and “cadets” etc should be taken to refer to either gender. T o avoid the repetitious use of “he/she”, “his/hers”, etc the male gender only has been used in the text.

The term “county” is used for an ACF unit commanded by an ACF cadet commandant and for which the terms “battalion” or “sector” are also used.

The term “company” is used to denote the ACF level of command commanded by a major and for which the terms “area” or “group” are also used.

Any person wishing to propose amendments to this handbook is invited to communicate this to the

HQ Support Command Cadets Training Development Team. Such proposals will be given consideration and, if considered necessary, appropriate amendments will be prepared and submitted for approval and publication.

CONTENTS

Introduction, aims and principles

Types of lesson

Five steps to effective instruction:

Step 1 - Identify the need

Step 2 - Plan and prepare the training

Step 3 - Deliver the training

Step 4 - Assess the trainees

Step 5 - Evaluate the training

Training the instructor

Who can deliver training?

Annexes:

A. Lesson plan

B. Hints and tips for helping cadets to remember learning

C. Motivating, inspiring and maintaining the interest of the cadet

D. Effective assessment.

E. Lesson evaluation form

CADET FORCES INSTRUCTIONAL TECHNIQUES (CFIT)

INSTRUCTOR HANDBOOK

GENERAL

Introduction

1. If young people are to be attracted to, and remain in, the Army

’s cadet forces, the quality of the instruction they receive will be paramount. Teenagers are beset by many distractions and to compete with these, the cadet experience must be fun, interesting, varied and rewarding.

2. A good instructor is one who creates the right conditions for learning to happen and finds ways of motivating the cadet. The scope and success of each lesson depends on your dedication, imagination, effort and approach.

Aims

3. The aim of the Cadet Forces Instructional Techniques (CFIT) package, comprising this handbook and formal training in the techniques, is to provide the instructor, whether an adult or a senior cadet instructor, with the knowledge, skills and attitudes to deliver the best training possible to cadets.

4. Army cadet training should aim to develop all aspects of the cadet (or trainee adult volunteer) – their physical skills; their knowledge and understanding; their attitudes and values.

Purpose

5. This handbook aims to lay out a comprehensive set of principles and guidelines for the effective instruction of cadets. It should be used by all adult instructors, senior cadets and others who are authorised to instruct cadets as their guide; both newcomers to training and those with existing teaching or training qualifications and experience. In addition it should form the basis of all training in instructional techniques, including cadet instructor cadres (JCIC, SCIC and CCF leadership cadre) and adult volunteer induction training.

Definition

6. For the purposes of this handbook, “instructing” is defined as:

'The process of helping learning to occur according to pre-set learning objectives' .

Training cadets

7. Youngsters may have slower reaction times and lack co-ordination, especially during growth spurts when they shoot up so fast that their brains cannot keep up. As their height increases, their centre of gravity lifts. This happens so quickly that the brain does not get a chance to calculate the new rules for balancing and clumsiness is often unavoidable. To deal with this, you may need to adapt normal military training – smaller distances, less weight, shorter sessions, smaller, simpler chunks of learning. High quality skills developed at this stage will stay with the cadet for the rest of their life.

8. Because the APC syllabus is progressive, the skills, knowledge and positive attitudes developed at one level provide the foundation for the next, therefore good quality instruction must start right from the Basic level and the cadet’s early experience of attending the detachment.

Instructors must ensure that during Basic level training cadets begin to develop the whole range of skills in their syllabus, both to maintain their interest and to provide a good foundation for later levels.

1

Principles of training

9. The principles of cadet training are laid out in the APC Syllabus. They are: a. Training should be planned so that it is steadily progressive for the cadet who might be in the ACF or CCF for five or more years. b. The gaining of the APC qualifications, which are tests of the individual cade t’s knowledge and capabilities, should be considered the normal achievement of the majority of cadets who make the necessary effort and have been properly trained. c. Training must be made interesting, imaginative and purposeful. Much of the instruction should include competitions, exercises and games. d. Knowledge by itself is of little value, it has to be applied. Lessons and tests should therefore be practical and out of doors whenever possible. e. The primary contribution of members of the Regular Army and Territorial Army to the Army’s cadet forces is to instruct officers, adult instructors and cadet NCOs on training courses, and to assist with testing. They may also instruct more junior cadets but this should be an exception to the rule. f. Cadet NCOs should be taught how to instruct and given opportunities to practise command.

Principles for cadet instruction

10. There are 3 principles for the planning, preparing, delivering, assessing and evaluation of effective cadet instruction:

Think Safety

Think Enjoyment

Think Achievement a. Think Safety . The safety of cadets is your first and foremost duty. As an officer, adult instructor or senior cadet you are required at all times to apply the safe system of training:

safe persons

safe equipment

safe practice

safe place b. Think Enjoyment. Being a cadet in the ACF and some CCFs is voluntary. Unless instruction is of a high standard and enjoyable (fun) right from the start, cadets will not stay.

Plan lessons so that cadets will enjoy them. c. Think Achievement . The Army’s cadet forces offer a progressive syllabus with many opportunities for cadets to achieve. In the ACF, your responsibility, in accordance with the ACF motto, is To Inspire to Achieve . Clear lesson objectives help cadets identify their achievements.

2

TYPES OF LESSON

Introduction

11. There are two main types of lesson: theory (or factual) and practical (or skills). They are generally delivered in different ways.

Theory lessons

.

12. Theory lessons will normally follow the format below:

Introduction

Main Body

Key Learning Point 1 (eg Countryside Code - 1. Guard against fire)

Key Learning Point 2 (eg Countryside Code - 2 .Fasten all gates) etc

Conclusion

13. An example might be a lesson on Military Knowledge – eg the detachment or contingent’s capbadge: a. Introduction.

Aim of the lesson – (By the end of the lesson each cadet will be able to state 4 facts about their capbadge)

Reason why/need for lesson e.g…….to know more about the Army, to be knowledgeable about why they wear what they wear, to be proud of being a cadet and wearing the capbadge.

Rules for lesson e.g. behaviour, note taking and question policy etc. b. Main Body.

KLP1 - What is the significance and purpose of a capbadge?

KLP 2 – The elements of and symbols on the capbadge

KLP 3 – The history of the capbadge

KLP 4 – Associations to the Army (including sponsor unit) c. Conclusion.

Summary

Brief Revision of KLPs

Assessment of cadets – list 4 facts about the capbadge

Any questions

Look forward/link to next lesson

3

Practical lessons

14. Most subjects in the cadet syllabus are practical and will be taught as practical lessons.

Note the following: a. Practical lessons can be most effectively taught using the EDIP method

(explanation, demonstration, imitation, practice). EDIP is used in the main body of the lesson as follows:

Explanation. Explain what the cadets are about to do, clearly and simply.

Demonstration. Demonstrate by showing and suggesting how the cadets might perform the skill. Make sure all the cadets can easily see what has just been explained. Try not to explain and demonstrate at the same time as the group needs to concentrate on the actual performance of the skill.

Imitation. Get the cadets to copy exactly what you have just performed.

Talk them through the actions step by step as they do them. Observe them carefully and provide help where necessary. You may have others to assist you with observing and helping the cadets. Give constructive feedback.

Practice. Get the cadets to practice. Give enough time for them to practice the skill several times over, giving them different scenarios or ways in which the skill may be performed. Continue to give constructive feedback, correcting where necessary.

As a simple EDIP example, the main body of a lesson on orientating a map could be run as follows:

Explanation – explain that to navigate successfully, the first step is to orientate the map, which means matching the symbols and features shown on the map to the actual features on the ground.

Demonstration – Gather the cadets around the map. Orientate the map, pointing out to the cadets which features and symbols on the map relate to which actual features on the ground (eg road, path, building, woods, hill).

Imitation – Cadets each orientate their map in the same way as the instructor.

Instructor gives guidance, e ncouragement and support; assesses cadets’ performance and gives feedback.

Practice – move to a number of different locations in turn and at each, every cadet should orientate the map, given support where required, be checked to see whether they have mastered the skill and be given feedback. b. Unless the skill is very simple, it should be broken down into small steps and EDIP applied to each one, for example in a drill lesson for each of the drill movements being taught. It may help to think of the fir st lesson when learning to drive a car: ’put your foot on the clutch (the pedal on the left) and press down, holding the pedal down; hold the gear stick firmly and move it across to the left and then up to the position marked 1. Slowly lift your foot off t he pedal….. etc’. Once someone has learnt to drive, they have repeated the skill so many times, it happens automatically.

Each step should be:

4

Explained

Demonstrated

Imitated

Practised

And then put together into a single action. c. When planning and delivering a skills lesson, you may wish to bear in mind the following points:

(1) Recognise that what might be easy for you, especially if you are an experienced practitioner, might be very difficult for the cadet who has never undertaken the activity before.

(2) Try to make the training as realistic as possible (within the bounds of safety).

For example, create real scenarios (eg in map reading, “Imagine you are leading your section on a fieldcraft exercise and you have to get to…..”) and wherever possible, use real equipment.

(3) Allow the cadets themselves to perform the skill, no matter how slow and cumbersome they may be – by all means demonstrate, but do not take over and do it for them (or let anyone else take over for them) or they will not learn.

(4) Youngsters have slower reaction times than adults so cannot react to situations as adults would. Their co-ordination is sometimes lacking and they may be clumsy, especially during growth spurts, therefore they often struggle to perform smooth and accurate physical tasks. This may impact on subjects such as drill, skill at arms and fieldcraft. Be aware of these limitations and make the tasks simple initially, with few decisions to be made by the cadet.

(5) Be aware that there are three stages to learning a new skill. The table below shows them, using ‘standing to attention’ as an illustration:

Stage

1

2

Stage

Cognitive

Associative

Description

Identification and development of the individual parts of a skill

(known as the cognitive stage)

Linking the component parts into a smooth action (known as the associative stage)

Example

Component parts include: standing tall; placing the arms by the side; holding the hands in a fist; placing the thumb straight in front of the fist, pointing the ground; placing the feet next to each other at an angle; holding the chin up; keeping the eyes looking forward etc eg moving the arms from behind the back to the side, clenching the hands into a fist shape and moving the left foot in next to the right with a firm step.

Training implications

Youngsters will be concentrating very hard on the overall action and individual parts may be clumsy, incorrect or missing.

Cadets rely heavily on instructor feedback at this stage. Simple instructions, such as ‘stand tall’, feet at an angle’, ‘chin up’, look straight ahead’ may be repeated until the cadet progresses into the second stage

Cadets can be given more freedom to experience and experiment with how the skill works and feels before being given feedback, however, incorrect actions must be corrected at this stage.

5

3 Autonomous

Developing the skill so that it is carried out automatically

(known as the autonomous stage)

Moving smoothly and correctly from ‘at ease’ to attention, without having to think about the individual actions

In this stage the cadet can carry out the skill without much thought, time and time again and can concentrate on the wider activity. They should not need much feedback as they should largely be able to recognise and correct their own mistakes.

The learning of physical skills requires the relevant individual steps to be put together, action by action, using feedback to shape and polish them into a single smooth action. Practice of the skill must be done regularly and correctly.

EFFECTIVE INSTRUCTION

Five steps to delivering effective instruction

15. Helping cadets to learn is clearly not about turning up and thinking “What shall we cover tonight?” Time beforehand needs to be spent in planning and preparing for cadets to benefit from their training and lessons. There are 5 main steps to delivering effective instruction to cadets:

5. Evaluate the training and implement improvements

1. Identify the need for training

2. Plan and prepare the training

4. Assess the trainees

3. Deliver the training

Step 1 - Identifying the need for training

16. It is de-motivating for a cadet to be taught what he already knows and demoralising to be taught something at too advanced a level to be properly grasped. You should cover the right subject material at the right level for the cadets you are instructing. As an instructor, you may be told what to cover, for example by the contingent or detachment commander, but if not, answering the following questions can help determine what should be covered in a period or series of periods of instruction:

6

What subject material does the APC syllabus say needs to be covered by the group?

At what stage in their training are the cadets – what do they know/can they do already? (ask the contingent or detachment commander, other instructors and the cadets themselves).

What gaps are there in their training?

How competent are they in the subjects they have been taught?

What future programmed activities require training to be delivered beforehand? (eg is there a weekend training event that requires a particular topic to be covered in advance?)

Here is an ACF example:

“I will be instructing a group of cadets who have recently passed their Basic test and need all subjects of the APC syllabus at 1 star. The detachment commander would like to make drill a priority as he would like the cadets to have the opportunity to march with the company on the Remembrance Parade in November.”

The cadets generally did well in their Basic level drill test, so should not need much revision.

Given that, they should have a period of revision on the first night, and then move on to the 6 remaining periods of the 1 star syllabus for the subsequent nights.”

Step 2 – Planning and preparing the training

17. It is important to ensure that all training is properly planned and prepared. The success of a lesson will usually be in direct proportion to the amount of planning and preparation put into it. To quote the old adage: “Prior planning and preparation prevents poor performance’. The following activities make up the planning and preparing process:

Consider the audience

Set a clear aim or objective

Plan the lesson including assessment of the students

Prepare the lesson

18. Consider the Audience . It is important to ensure the training is at a level appropriate to the cadets you are instructing, so before you do anything else, think about the members of the group you will be working with. Make a few notes if you wish. Ask yourself the following questions:

What age are they?

How many are there?

What do they need/want to get out of the lesson?

What can they do already?

What do they know already?

What are their physical capabilities?

What motivates them? What do they enjoy? What are their interests (in and outside cadets)?

How best do they learn? (theory, practical or a combination of both)

How long is their span of concentration?

Are there any specific learning difficulties (eg dyslexia) or disabilities?

How mature are they?

7

What learning styles do the individuals have? (do they learn best through seeing and reading; listening and speaking; touching and doing, or a balance or two or more?)

Are there some cadets who have missed training or need additional training?

For example

“Next week I am going to teach first aid to a group of about six cadets. They are aged 14 &

15. They are reasonably competent first aiders, though one has recently been transferred from another unit where they have done little first aid recently, so may need some revision or pairing up with one of the most competent first aiders. The group tends to enjoy practical work and some of them are fairly good at acting out being casualties, so I’ll make the session as practical as possible. I’ll just have to think about pairing up our Asberger’s Syndrome cadet with one of the other cadets he gets on well with.”

19. Set a Clear Aim or Objective . Before doing any planning or preparation, you must be clear in your mind what it is you want the cadets to achieve in the lesson. To do this, start with a simple, clear, relevant, measurable and achievable objective, which is based on what each of the cadets will have achieved at the end of the lesson. Having a clear aim for the lesson in mind at all times will ensure you keep things focused throughout the planning, preparation delivery and evaluation of the lesson. The aim should not be a vague statement or what the instructor is to have achieved.

The wording for an aim should begin:

By the end of this lesson you will be able to………….

Not

This session aims to tell you about……

Nor

For example:

By the end of the lesson you will be able to tie and untie a reef knot in a sling correctly.

Not

What I aim to cover today is….

‘You should know about reef knots’ or ’In this lesson I am going to tell you about reef knots.’

Say

'By the end of this lesson you will be able to strip and assemble a cadet GP rifle'

As opposed to

'The aim of this lesson is to teach you to strip and assemble a Cadet GP rifle ’.

Other examples are

8

Fieldcraft - ‘ By the end of this lesson you will be able to move tactically without a rifle'

First aid - ‘By the end of this lesson you will be able to list the immediate actions to be taken at the scene of an accident .’

Drill – ‘By the end of this lesson you will be able to march correctly in a straight line, and halt.

’

20. Plan the Lesson. This step should result in the production of a lesson plan. There is no laid down format for a lesson plan, but an example can be found at Annex A. Importantly, what you will need to have is a clear beginning, middle and end. In order to plan the lesson you will need to:

Identify and organise the content . a.

(1) The content of most of what you will be teaching cadets will be laid down in

The APC Syllabus and The Cadet Training Manual (both available on Westminster).

You should study carefully the relevant sections of these publications and ensure that your training covers the subject material laid down, basing the content of your lessons on these and any other authoritative sources of information: eg, Pamphlets

5c & 21c, current Red Cross/ St John’s Ambulance Handbook, DofE Handbook etc.

Content can change over time, so ensure that you are referring to and delivering the most up to date syllabus and training material.

(2) Ensure the content contains all that is relevant and nothing that is irrelevant.

Decide what the cadets you are going to instruct really need to know (or be able to do) in order to achieve the objective you have set ……and eliminate anything else.

(3) The number of periods allocated to particular subjects in the APC syllabus is intended as a guide. You should take into account the standards and needs of individual cadets when deciding whether more or fewer are required. Do not give cadets, especially the younger ones, too much in any one lesson.

(4) Always ensure plenty of time for practice.

(5) Establish the key points that need to be covered in the lesson and arrange them in a logical sequence. This may be laid down in a handbook or manual, or you may need to identify the content yourself. If it is the latter, then begin by

‘brainstorming’ ideas for what you may need to include. The logical sequence should include:

(a) Preliminaries

– ground rules, safety points, revision points, administration.

(b) Main body - each of the key points in logical order.

(c) Concluding points – summary points, assessment, look forward, closing administration (clearing up, packing away, results). b. Select methods for delivering the training . Be aware of attention span – no single activity should last too long. Try to get maximum involvement for each of the cadets.

You may use different methods for different parts of the lesson. These may include:

(1) Practical work . All skills subjects should be taught as practical lesson. This should include first aid and navigation as well as drill, turnout (cleaning boots is a practical skill!), skill at arms, fieldcraft and expedition skills. For skills lessons, you

9

should use the EDIP (explanation, demonstration, imitation, practice) method (see more on this in the section above on Types of Lesson). Even theory lessons can be made practical, for example by drawing posters, eg to show the badges of rank, map symbols or illustrate aspects of the Countryside Code.

(2) Games.

For example camouflage and concealment naturally lends itself to games including all sorts of variations of hide and seek, but there are many other possibilities.

(3) Puzzles . A whole range of puzzles can be created. For a small investment,

Ordnance Survey map jigsaw puzzles, centred on the detachment hut or school, can be ordered from their website.

(4) Worksheets.

A set of exercises or questions for cadets to do or research.

These can be on paper, and can be used for individual work or group tasks. If paper and copying are a problem, the worksheet can be produced on large sheets of paper, written in advance on the board or produced on a PowerPoint slide.

Examples can include:

Map work - Matching OS map symbols to their description.

Military Knowledge – fill in the blanks, match rank badges to their name, research (eg ‘Make a list of ten things you can find out about your capbadge’).

Skill at Arms – name the parts on a drawing or photo.

(5) Quizzes and competitions . Put the cadets into teams and get them to answer questions – or perform skills (eg simple drill movements). Run a simple drill competition between two sections or squads.

(6) Instructor-led explanation . It is tempting to over-use this method, and it should be kept to a minimum as cadets will soon get bored being lectured to. For certain topics and groups it will be required – for example elements of weapon handling lessons, but even within this, the style should be interactive – ask questions; get cadets who may have already done the lesson to name the parts, or the steps involved.

(7) Whole class discussions . Short discussions involving the whole group can sometimes be useful, for example, a group brainstorming exercise on what to pack in a rucksack for an expedition. Set rules for the group discussion, including the following:

One person speaks at a time

Do not interrupt

Raise your hand if you want to say something

Make sure what you have to say is about the topic

Write your point down so you do not forget it if there are several people who want to talk

Assign one person to write down important points (either on paper or on the board)

(8) Smaller group work, group/team exercises and work in pairs .

Encourage work as a group or team. For example in fieldcraft, get groups of cadets to work together as designated teams. Particularly in practical lessons, use the

‘buddy-buddy’ system regularly, for example, get cadets in pairs to look out for their turnout and their drill movements or to work together as a pair when cooking rations.

10

(9) Project work . Set cadets a project, for example, putting together a model kit for the contingent or detachment to use for illustrating fieldcraft principles or creating a wall display on a subject related to the ACF, CCF or British Army.

(10) Quick lessons . Carry out a quick revision lesson on an APC syllabus subject at the beginning and/or end of each cadet training event.

(11) Research.

Challenge the cadets to find out about a subject. – set individuals or groups certain topics or skills to research and become master of.

Then ask the cadets to return to cover them with the rest of the group, eg give each cadet or group of cadets one or two of the reminders in the Countryside Code and give them a week or two to research some examples of where it has gone wrong or right. Get them to present their findings to the rest of the group.

(12) Scenarios.

Various APC syllabus subjects lend themselves to the use of scenarios. First aid can be brought to life by casualty scenarios. Even without casualty simulation equipment, unconscious casualties, sprains, simple fractures, choking, shock etc can be built into a scenario. Fieldcraft also lends itself, with a good ‘story’ about why a particular action needs to be carried out, for example, revise ‘obstacle crossing’ by setting a scenario of having to get to the other side of the field without being seen by the enemy, who are located on the ridge opposite.

(13) Using Assistants/Mentors.

Think about using the skills and knowledge within in the group. Eg for the skill at arms lesson on fitting a sling, especially if there are not enough slings, pair up cadets - one who already knows how to fit a sling with one (or two) who don't. As you go through the ‘demonstration’ part of the lesson, you should ask the cadets who know how to fit a sling to demonstrate the steps you are describing. For the ‘imitation’ part of the lesson, the new cadets should go through the steps with the experienced cadets mentoring (not doing!!!).

There might be a cadet or two who have mastered map reading in their school lessons and who can be of great assistance to you when managing a group of cadets on map reading lessons.

Some additional techniques for helping cadets remember information they need to learn are at Annex B. c. Plan how to maintain the cadets’ interest. Plan in how you will maintain the cadets’ interest throughout the lesson. This is a fundamental part of successful instruction.

A guide on motivating, inspiring and maintaining the interest of the cadet learner is at

Annex C. d. Plan how to assess the cadets. Plan how you will assess that the cadets have achieved the aim or objective of the lesson and how you will give them feedback. More on effective assessment is at Annex D. e.

Decide on training location(s). Decide where the training is to take place indoors, outdoors or both. Bear in mind the following:

–

(1) Check the location is suitable. This may involve carrying out a recce. You may decide to take a lesson in more than one location – for example, a classroombased explanation, followed by an outdoor practice.

(2) If you are training in a classroom, think about the layout. There are many ways of laying out a training room. For practical lessons, furniture will generally be removed or pushed back against walls, giving room for the activity. For the few theory lessons on the APC syllabus, consider how you want the cadets to be

11

seated. You may change it during the lesson. You may use chairs or sit on the ground/floor. There are several options for seating layout:

(a) Traditional – desks or chairs in rows separated from each other.

Rarely used. Useful for individual tests or pieces of individual work where no consultation is permitted.

(b) Straight row or rows. Sometimes used. Allows cadets to consult with those either side, but may be difficult for the instructor to move round the group to assess or help with work

(c) Pairs. Sometimes used. Allows cadets to work in pairs. Allows easier movement around the class. Desks/chairs can be straight on to the front of the class or angled for a less formal approach.

(d) Groups. Sometimes used. These may be on the floor, groups of chairs or may be created by using large tables or groups of tables pushed together. Allows cadets to work in small groups and easier movement around the class, though positioning is important to ensure that some cadets do not end up with their back to the front of the class and any visual aids being used.

(e) Semi-circle, horseshoe or U-shape. Sometimes used. Useful for group discussion with the whole class.

(f) Circle. Occasionally used. Can be useful for holding a discussion with the whole group.

(3) Fieldcraft and navigation require a large element of out of doors instruction and practice, ideally in open countryside. However, suitable training can also be carried out in parks, playing fields, local woodland or other local green or open spaces. You must always ensure that the correct permission has been obtained for the use of the land for cadet training. Bear in mind you may need to plan a fallback

(for example in case of a clash of bookings, major fault or adverse weather). Seek further advice from your Contingent Commander, County Training Officer and

Training Safety Adviser. f. Determine equipment, materials and dress needed. Decide what equipment, transport, assistance and other support you might need. You will need to make sure that you order equipment through your CAA or CTT in plenty of time for it to be acquired and delivered. You will also need to decide what dress is required. Most cadet training is in uniform, but for some activities, such as physical recreation, other orders of dress, such as

PT kit will be required. If training is going to be outdoors, you will need to remind the cadets to bring jackets, gloves etc. g. Determine assistance required. Determine whether you have or will need assistance, for example, in the form of another adult or one or more senior cadets or CTT support. If so, how are you going to use them? What will their role be? When and how will you brief them? h. Plan the evaluation of the success of the lesson. Think about how you will evaluate how the lesson went. How will you get feedback from the students? Will you ask someone to observe the lesson to give you feedback? How will you evaluate it yourself?

What will you be looking out for? i.

Lesson plan. Once you are clear on what you want to achieve and how you are going to achieve it, produce a lesson plan to give you a structure and guide for your lesson.

12

The amount of detail to be included in the lesson plan is up to you. If you have taken the lesson many times before and are very familiar with the content, materials, method and structure, you may only need a few bullet points. If this is your first lesson in a particular topic, you may need significantly more – perhaps with use of a highlighter pen to bring out your key points (or even different colours for different topics). You will need to decide what will happen if you are unable to take the lesson. Do you need to produce a sufficiently detailed lesson plan so that someone can cover for you? Always have the aim written down so that it remains foremost in your mind.

(1) Plan the beginning of the lesson, which may include:

(a) Roll call / checking all cadets are there.

(b) Introduction (may include title and explanation of the incentive(s) for undertaking the lesson).

(c) Context – where this lesson fits with other training.

(d) Aim/Objective(s).

(e) Safety.

(f) The content and format of the lesson.

(g) Ground Rules – eg on behaviour, asking questions, note-taking, being excused.

(h) Timings.

(i) Relevant revision of previous learning.

(2) Plan the main body of the lesson, keeping teaching points in a logical sequence. Learning should be broken down into small, achievable steps. For each teaching point, think about how you are going to cover it. In a skill at arms lesson, this will be fairly formally laid down, but for some lessons, you can let your imagination go. Some military knowledge lessons can be very dull, but you can liven them up by the way you run the lesson. For example, you can make a set of cards, half with pictures of the badges of rank and half with the names of the ranks. Hide them and get the cadets to find them, match them and lay them out in the right order. Do this first with a slide or poster of the badges of rank available, then after a short break, try it without. This helps to develop the cadets’ observation skills, too!

(3) Plan the end of the lesson, which may include:

(a) Summary/review of material covered.

(b) Some form of assessment to confirm the objective has been achieved by all of the cadets, unless already done.

(c) Clearing up.

(d) An opportunity for the cadets to ask questions and to reflect on how successfully they have achieved the lesson objective.

(e) An opportunity to give feedback on student performance.

(f) A look forward to the next relevant lesson(s)/learning.

13

j.

(g) Feedback from the students on how they felt the lesson went.

Determine timings.

(1) Training periods in the APC Syllabus are normally 30 minutes in length excluding time needed for setting up and packing up.

(2) Estimate how long each part of the lesson will take. Is there just the right amount of content in each part of the lesson and the lesson as a whole, or is there too much or too little? Write the timings on your lesson plan as a guide for when you are taking the lesson.

21.

Prepare the lesson. You will need to spend time on, and take care with, the preparation of your lessons. Preparation should include: a.

Knowledge and skills. Ensure your own knowledge and skills are comprehensive and up to date:

(1) Look up/research any information you may need for the lesson.

(2) Know the subject material thoroughly.

(3) Be able to carry out any skills yourself confidently and competently.

(4) Revise where necessary. b. Instructional materials. Obtain or prepare any instructional materials (training aids) you need. Ensure your materials are up to date. Make sure, where appropriate, training aids are working correctly, eg if you are using PowerPoint slides, check the slides work and are formatted correctly on the PC/laptop and that it displays effectively through any projector you are using and can be seen clearly by the cadets (eg colours display clearly).

Materials may include:

(1) Worksheets and handouts.

(2) Equipment, eg weapons for skill at arms, cam cream for fieldcraft, bandages and ResusciAnne mannequins for first aid, iron and ironing board for turnout, maps and compasses for navigation.

(3) PowerPoint slides – use these sparingly – they can be a very valuable aid, but be very aware of the dangers of ‘death by PowerPoint’!

(4) Models (consider making up your own model kit for briefing cadets on fieldcraft exercises – string, coloured blocks to show own and enemy positions, coloured heavy duty ribbon for roads, rivers etc). You can also give the cadets a project to build a papier mache model on which you can teach fieldcraft principles during the long winter nights.

(5) Improvised equipment. Where it is not possible to use the ‘real thing’, improvised equipment may be better than no equipment at all. For example if we apons are not available for a ‘movement with and without weapons’ lesson, moving with a wooden cutout, is better than nothing. In the middle of winter when it is too dark and inclement to train outdoors, obstacles for ‘elementary obstacle crossing ’ can be made out of string, chairs and tables (just remember to ensure safety)!

14

(6) Posters and display materials. Some very useful posters, eg badges of rank and parts of the rifle, are available from military sources.

(7) Films or clips of film. These can be about syllabus subjects, such as fieldcraft, from war films or examples of the use of first aid from films with a medical theme or can be used for moral lessons, for example ones relating to teamwork, leadership, values and standards. c. Training Environment. Prepare the training environment (eg classroom, other room, outdoor area). Remember the following:

(1) Seating . Arrange the seating as you want it.

(2) Desks . If you have desks, how do you want them arranged?

(3) Climate (indoors and out) . Will it be warm enough? Cool enough? If outdoors, dry enough? Calm enough? If not, decide what you must do about it.

(4) Lighting . Will the cadets be able to see what they are doing? With outdoor lessons, think about what time it gets dark and whether, if you are in woodland, there will be enough light.

(5) Safety. Always think safety in training:

(a) Whether you are in the classroom or out of doors, you must ensure the safe system of training is in place. Follow the guidance in JSP 535 Cadet

Training Safety Precautions (The Red Book).

(b) Consider what risks there might be to the safety of the cadets.

(c) Consider what control measures need to be put in place to minimize the likelihood and impact of a risk becoming an accident or incident.

(d) Ensure your lesson plan includes any safety points you must brief to the cadets and make sure they are briefed at the start of your lesson. Also think too about the need to brief any training assistants (cadet or adult) that you may have helping you.

(e) Certain subjects require those running it to be properly qualified.

Where required, check to ensure that you or your assistant(s) have the right qualification and that they are in date.

(f) Whatever training you are undertaking always ensure that suitable first aid cover is available.

(g) If using potentially hazardous equipment, require each cadet to demonstrate the safe operation of the equipment. At the most formal level, this is illustrated by the requirement for the cadet to pass the Weapon

Handling Test before firing a weapon.

(h) Remember that teenagers have a lack of experience and their enthusiasm may sometimes outweigh their judgment. Be conscious of the

15

tendency of teenagers to be unaware of the consequences of risks. Some may therefore have a willingness to take risks that an adult normally would not.

(i) A safe environment includes how the cadets behave towards one another - do not tolerate any form of bullying d, Distractions . Try to eliminate any distractions, such as irrelevant materials on the walls, things happening outside of the window and even your own mannerisms. Have a strategy for dealing with disruptive cadets so that they do not become a distraction to others. e. Rehearsal. Run through or rehearse the lesson.

Step 3 – Deliver the training

22. You cannot expect to be a fully competent instructor the very first time you stand up in front of cadets. There are many aspects to delivering effective training and, a bit like learning to drive a car, the various skills only come together with practice. It will help if, in the early stages, you are supported by one or more good instructors to give you training, guidance and feedback.

23. Techniques for delivering an effective lesson include: a. Explaining clearly the aim (and objectives if any) of the lesson and expecting the cadets to achieve it/them. Do this by explaining clearly at the start exactly what will be expected of the cadets during and at the end of the lesson. b. Keeping your lesson focused throughout on achieving the aim or objective. Do not waffle or go down rabbit holes, or the cadets will soon lose interest. Do not let the cadets distract you with ‘red herrings’. c. Keeping explanations simple and real: Break complex subjects down into small bitesized chunks (individual learning points) and make them relevant to the cadets. d. Engaging the cadet by maintaining eye contact:

(1) Look at members of the group the whole time.

(2) Speak to individuals, particularly at the back and not to walls, windows, e. ceilings or light fittings (they are notoriously disinterested students).

Thinking about your voice and how you are communicating:

(1) Vary the pitch of your voice. Do not be monotone.

(2) Be audible - speak loudly and clearly without shouting.

(3) Think about pace. Try generally to keep a steady pace – not too fast (often b rought on by nervousness) or too slow (it’s dull!). You can vary pace for effect, but always avoid speaking too quickly.

(4) Remember the value of silence. A pause is a very effective way of getting a student's attention.

(5) Use non-verbal communication effectively. Non-verbal communication covers aspects like facial expressions, eye contact, gaze, appearance, gestures,

16

personal space and posture. The importance of an instructor's body language is highlighted by the fact that the impact of a message in a face to face situation is around 7% verbal (the actual words only), 38% vocal (the tone of voice, inflection and other sounds) and around 55% non-verbal.)

(6) Using appropriate language:

(a) Use simple, concise language that the cadets will understand.

(b) Avoid jargon.

(c) Explain all the abbreviations you use unless you know that the cadets already know them.

(d) Use terminology appropria te to the level of the cadets’ understanding.

(e) Avoid the use of the word ‘I’; make the most of the word ‘you’.

(f) Never, ever use bad language.

(7) Speak clearly. This may mean slowing down a little. If you know you have a strong accent and a tendency to speak quickly, make sure you pronounce individual words carefully, keeping sentences and explanations short. f. Avoiding your personal mannerisms: g.

(1) Physical Mannerisms – There are many potential types of physical mannerisms, which can include:

Waving hands

Moving around

Fiddling with fingers, hair, jewellery, belt

Hands in and out of pockets

(2) Verbal Mannerisms, including:

Regular hesitations, including ‘um’ and ‘er’

‘Right?’

‘You know’

‘OK?’

etc

Maintaining enthusiasm. Do this by:

(1) Believing in what you are teaching.

(2) Never appearing bored.

(3) Being positive about what you are teaching – never ‘rubbishing’ it in front of h. Making your cadets feel respected and valued. Make each one feel they are an important part of the group. cadets.

17

i. Being fair, firm and approachable. Maintain a balance between sympathetic understanding and effective discipline. Do this by setting the standards that you expect at the beginning of the lesson. j. Being flexible – if a lesson is not quite running as you wish, do not be afraid to make some minor adjustments or try something different. k. Giving the cadets clear, sensible and accurate instructions. l. Recognising that as part of growing up, teenagers may be self-conscious and that they may:

(1) Find direct eye contact difficult.

(2) Be shy and reluctant to ask questions. m. Maintaining discipline. Try to anticipate when cadets may be becoming restless or individuals may become disruptive. Do not be afraid to remove those who are distracting or disrupting the others from learning. n. Sticking to the subject. Do not wander off the topic or let yourself get distracted by:

(1) ‘Red herrings’ and ’rabbit holes’. Put off answering questions that are not relevant to the lesson. You may need to answer them later, eg a question about camp, but not during your lesson, so let the cadet know you will answer the question later (and write it down so that you don’t forget).

(2) I ndividual cadet’s needs. If an individual cadet has a particular need, like not being able to carry out a particular drill movement properly, rather than have the rest of the group waiting while you deal with it, address it separately after the lesson. o. Maintaining variety. Do not let cadets become bored. You should already have a variety of activities planned into your lesson to maintain their interest – you now just need to make sure they happen! Remember to:

(1) Promote mental activity by asking questions during the lesson and organising short quizzes.

(2) Promote physical activity through the practice of any skills being taught.

(3) Answering cadets

’ questions:

(a) Willingly.

(b) Accurately – find out the answer and get back later if you do not know it (write it down so that you don’t forget).

(c) Without judgement (there is no such thing as a stupid question) – be positive and encouraging even to the most simple of questions.

(4) Setting a positive example – be the best role model.

(5) Using training aids effectively.

(6) Assessing the cadets regularly during the lesson (by observation and/or questioning for example) to determine whether they are achieving the aim and any

18

objectives you have set and giving positive and constructive feedback including frequent praise and encouragement. See more in step 4 below.

Step 4 - Assess the trainees

24. It is most important to check the cadets’ or adult volunteer’s progress regularly to ensure that each one is achieving the aims and objectives you have set. Never assess that which you have not taught:

“Experience is a hard teacher because she gives the test first, the lesson afterward.”

Vernon Law

25. As part of your lesson planning you will have determined what methods of assessment you would use. During the lesson you will need to observe and question to see how the cadets are progressing, as well as setting any more formal assessments. It is also most important that you give feedback on the outcome of the assessment. At the least, this should comprise a few encouraging words and a pointer or two on areas for improvement. There is more on effective assessment at Annex D.

26. You must ensure that part of the assessment process is giving timely, honest and constructive feedback.

Step 5 – Evaluate the training

27. At the end of the lesson, you will no doubt wish to breathe a sigh of relief, but it’s important to take the time to finish the process and evaluate how it has gone, giving you the chance to reinforce in future that which worked well and to implement any improvements that you have identified are needed. Be prepared to be self-critical. Actively review your own progress and find opportunities for self-improvement. Be positive and responsive to feedback you get from others.

28. Aim, as a minimum, to try and determine the following: c. d. a. To what extent the aim/training objectives have been achieved. b. If not, what further lessons are necessary to achieve them and what aspects must be covered in greater detail?

What aspects went well and should be used again?

What could be improved?

29. Get your feedback as soon after the lesson as possible while it is still fresh in your and others’ minds. A form designed to help evaluate any training you deliver is at Annex E.

30. Use the following techniques to help you evaluate any training you have delivered:

Re-run the lesson in your head, asking yourself the questions above. a. b. Ask the cadets for feedback. You can do this by:

(1) Informal questioning.

(2) Holding an open forum with all of the cadets at the end of the lesson where you can ask them for feedback on specific areas, not just the lesson as a whole, but different sections and other matters such as the equipment, training materials, method of learning, environment etc.

19

(3) Getting written feedback. This can be as simple as getting each cadet to write on a piece of paper the 3 best things about the lesson and the 3 things that would make it better in future. You can also get written feedback by using a feedback form like the example at Annex E. c. Use the results of your assessments of the cadets. – if they did not achieve what you set out for them to achieve, you should ask yourself what you can do next time so that they do achieve what you wanted. Was the aim too ambitious, did you not explain things clearly enough, were there too many distractions, did you fail to break things down into small enough chunks? Did it need two periods instead of one, did they need more practice at something? Was the content or language too complicated? d. Ask anyone who assisted you to give you their feedback. As with the cadets, this can be done orally or with written feedback. e. Ask someone to sit in on your lesson and give you feedback. Choose someone who you know will be both honest and constructive.

TRAINING THE INSTRUCTOR

31. Some adult instructors will come to the cadet force already qualified as teachers or trainers.

Others may never before have been required to stand up in from of a group and speak. All will need some instruction in the delivery of lessons to cadets, but the amount and level required may vary considerably.

32. In the CCF, officers are not permitted to deliver unsupervised training in the APC syllabus until they have attended the CCF Basic Course at the Cadet Training Centre, Frimley Park.

33. In the ACF,probationary instructors (PIs) will be trained in CFIT and given the opportunity to practise during their induction training. The subject material is covered in increasing detail during the three ACF induction courses – basic, intermediate and advanced. During the basic induction course (BIC) the students will be introduced to CFIT and be asked to apply some simple techniques to delivering a short 15-minute theory period at APC basic level. During the intermediate induction course (IIC) they will learn about delivering practical lessons and will deliver a short practical lesson at APC basic or one-star level. During the advanced induction course (AIC) they will cover the remainder of the CFIT syllabus and be expected to deliver full lessons in at least two subjects at basic or one-star level. A crucial part of the AIC is an assessment of the PI’s instructional technique and ability. The syllabus and assessment requirements for each of the three courses is as follows: a. BIC

Introduction to planning and preparing training

Introduction to delivering training and assessing cadets' performance

Introduction to evaluating training

Simple instructional period (theory) - preparation

Simple instructional period (theory) - delivery and student assessment

Simple instructional period (theory) - evaluation of instruction b. IIC

Planning and preparing skills training

Delivering effective skills training

Assessing cadet performance (skills)

Evaluating and improving training – skills lessons

20

Simple instructional period (skill) - preparation

Simple instructional period (skill) - delivery and student assessment

Simple instructional period (skill) - evaluation of instruction c. AIC

Planning a training event

Preparing a training event

Delivering effective training

Assessing trainees

Evaluating training and implementing improvements

Guided/mentored preparation for a practice APC syllabus lesson

Planning, preparation, delivery and evaluation of a basic or one-star APC syllabus lesson.

Feedback on the planning, preparation, delivery and evaluation of the practice lesson

Guided/mentored preparation for a final assessed lesson.

Planning, preparation, delivery and evaluation of a final assessed lesson (APC basic or one-star subject)

34. Junior and senior cadet instructor cadres (JCIC, SCIC and CCF Leadership Cadre) and

CFIT should not be taught as a single body of presentations, followed by a full teaching practice.

Delivering training, like so much of the cadet syllabus, is largely a practical skill and, just like stripping and assembling a rifle, each of the components need to be learnt and practiced before reaching the stage of delivering an entire lesson smoothly and effectively. The delivery of training using CFIT should, therefore, aim to break the subject down into individual techniques and students should be given the opportunity to practise these separately and receive feedback before having to bring them all together into a complete lesson.

WHO CAN DELIVER TRAINING

35. ACF officers and adult instructors and CCF officers who are not already qualified to deliver training, including cadets not holding an SCIC or CCF Leadership qualification, may assist a qualified instructor, may supervise cadets being instructed by a qualified senior cadet or may deliver short instructional periods under the direct supervision of a qualified and experienced adult instructor. ACF commandants and CCF contingent commanders should satisfy themselves that all individuals are delivering training to the required standards through regular observation of lessons.

36. There are certain subjects where only those who are formally qualified may deliver instruction. These include: a. Skill at arms . An instructor may not teach skill at arms, including practice periods, revision and weapon handling tests, until he has attended and passed the Skill at Arms

Instructor course. However, anyone who has previously passed the former adult instructor

(AI) course retains grandfather rights to instruct skill at arms in accordance with HQ

Support Command policy. b. First aid. An instructor may take periods of first aid only when qualified in accordance with current policy. County First Aid Training Officers (CFATOs) are able to advise on current policy, which is published by the Army Cadet National First Aid Adviser and available on Westminster. c. Navigation.

Any qualified adult instructor may instruct and assess cadets in the

APC navigation syllabus. However, although ACF two-star navigation is aligned to a

National Navigation Awards Scheme (NNAS) bronze award, this award may only be made when both the instructor and the assessor are approved and registered by NNAS, through

21

the Army Cadet National Navigation Adviser. Similarly, CCF cadets may only earn NNAS awards when they have been taught and assessed by approved and registered instructors.

22

Annex A to

CFIT Handbook

LESSON PLAN

Lesson Topic:

Syllabus

Subject:

Description of group to be instructed:

Need for training:

Location:

Duration

(time):

References:

Equipment:

Handouts/

Worksheets:

Preparation:

Dress:

Risks/Safety:

Ser Content

1 a

INTRODUCTION

Preliminaries: (Nominal Roll; Instructor/Lesson Title; Dos & Don’ts;

Notetaking; Questions; Equipment)

Revision:

Introduction to topic:

Aim of lesson/session:

Reason why/Incentive/Need:

Safety points:

2 MAIN BODY – DEVELOPMENT

Time

(mins)

Remarks

A-1

c b

3 CONCLUSION

Summary:

Questions from class

Assessing cadets:

End of lesson admin (results; pack away kit; clean/tidy classroom):

Look forward:

A-2

Annex B to

CFIT Handbook

HINTS AND TIPS FOR HELPING CADETS TO REMEMBER LEARNING

There are many ways of helping cadets to remember information. These are known as mnemonics. Some people will prefer certain techniques to others. The main point is that actively using and thinking about new information makes it more memorable and aids the learning process.

Below is a list of examples of the more common mnemonics which can aid the retention of information.

Acronyms

An acronym is a word made up of the initial letters or parts of words in a list, e.g. GRIT

(Group, Range, Indication, Type of fire).

Rhymes

Rhythm, repetition, melody, and rhyme can all aid memory. For example, even the simple addition of familiar rhythm and melody can help. Many children learn the letters of the alphabet to the tune of "Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star."

Acrostics/Sentences

Acrostics is when the initial letters of a list of words to be remembered are taken and made into a salient or funny rhyme e.g. Richard Of York Gave Battle In Vain = 7 colours of the rainbow.

Vivid Stories

Used to remember a list of items by incorporating the items into a story.

Chunking

Grouping digits, letters etc together, e.g. a list of numbers 1918106619451485 can be remembered as a series of dates or 1918/1066/1945/1485.

Examples

Real life examples can be used to aid the retention of information and show cadets how one piece of information can be associated with another.

B-1

Annex C to

CFIT Handbook

MOTIVATING, INSPIRING AND MAINTAINING THE INTEREST OF THE

CADET LEARNER

It is your responsibility as an instructor to motivate cadets and maintain their interest. You need to provide stimulating, inspirational and fun sessions that will whet young people’s appetite for the cadets and encourage them to keep coming. The points below will help you to do this. o Spend time and care on planning. o Ensure lessons are well organized and well structured o Put the cadet at the centre of your lesson planning

– consider what they will be feeling and learning throughout the lesson – will they be bored or motivated? o Keep periods relatively short. o If need be, build in short breaks, even if the cadets just stand up in their place and stretch their legs for a moment. o Aim for maximum activity (mental or physical) for the cadets. o In factual lessons, use games, discussion, quizzes, scenarios, team tasks, research as ways of making the training interesting. o Explanations, ie you talking, should be kept short o Wherever possible, make lessons practical:

Always teach skills subjects as practical, handson lessons, never by ‘chalk and talk’ or presentation.

A skill can only be perfected by practice, so build in time for the cadets to practise until the required standard is reached.

In factual lessons try to introduce challenges – research, quizzes etc (eg for the

‘History of the ACF’ lesson, pin up some historical information around the room and get cadets to go round finding the answers to a set of questions. You can, if you wish, give individual cadets specific questions, that they then have to brief to the rest of the group.) o Plan to use different senses: not just hearing, but sight, sound, touch and even smell and taste where relevant (cooking rations). The more senses he uses the longer his interest is maintained and the more effective his learning. o Promote mental activity by getting the cadets to think:

Relate the subject matter to the cadets’ own experience

Question the cadets regularly during a lesson.

Organize short tests or quizzes at the end of the lesson.

C-1

o Be enthusiastic, confident and energetic and really believe in what you are trying to teach. This may require you to put on a performance, just as an actor might do. o Establish a rapport, by eye contact; smiling (often and readily) and giving approving nods and gestures (eg thumbs up). o Give cadets confidence in you by knowing thoroughly the subject matter you are going to cover. Be up to date and current, by keeping abreast of developments in syllabus subject material. o Be able to ‘do’ any skills you are teaching well, competently and confidently. o Encourage the interest of the cadets before the lesson by telling them what they are going to do and what they will achieve at the end. o Give them an incentive – where possible make this relevant – eg if they do well at skill at arms they will pass their weapon handling test and will be able to go on the range and fire the weapon. o At all times maintain yourself the highest standards of behaviour and appearance and expect the same from your cadets. o Communicate clearly and at the appropriate level. Regardless of the level of the class or the subject, keep explanations simple. Remember that communication is a two-way process – listen as well as speak. o Work within the cadets’ limitations o Keep the content simple, clear and relevant o Don’t expect too much too soon. o Divide learning into small chunks. Cover one small topic at a time and build the topics up into a whole. Think o f the last time you had to do something you’d never done before and remember that to someone for whom a subject is completely new, those chunks may need to be very small. For example, try using (including demonstrating) the following small steps when tea ching ‘standing to attention’ in drill. Explain each step, then get the cadets to follow the step; check they have understood and correct major errors:

Stand up

Place your heels together

Keeping your heels together stand with your toes about 3-4 inches apart

Hold your arms straight out in front of you, palms facing each other

Now make a ‘thumbs up’ with both hands

Place your thumb down on top of your fist

Swing your arms down so that they are by your side, keeping your thumb to the front

Imagine you have a piece of string tied to the top of your head

C-2

Imagine the piece of string is being pulled upwards, so that your body becomes straight

Hold your bottom and tummy in and shoulders back

Keep your mouth closed

Look straight ahead focusing on a point at eye level o Make the subject matter real to the cadets – illustrate with examples relevant to them and their experience. o Treat the cadets like you would like to be treated when you are learning or being evaluated on some new task or skill. o Show patience – sometimes a lot of patience! Concepts that may be second nature to you may be a real struggle for teenagers who are encountering them for the first time. o Give the cadets confidence and a sense of achievement by encouraging them to try new things. o Young people will generally respond well to being given responsibility, as long as they are given real responsibilities. With a mentor, teenagers will learn – make them responsible for their learning. Eg make it clear that it is their responsibility, with your help all of the way, to be at the standard required to pass their star level tests. You must, of course, provide them with the support they need to achieve this. o Give cadets opportunities to achieve and allow them to develop in areas where they have the greatest strengths, otherwise they will be lost to their other interests in life. o Take an interest in the cadets’ development. Try to understand their needs. o Lessons should be youth focussed. Each cadet should be treated as an individual and lessons will need to be developed to ensure everyone benefits from the instruction. o Do not promise what you cannot deliver, for example, make sure that you have everything in place for an evening on the range before you tell the cadets that they will be shooting. o Introduce an element of competition, but ensure you make it as inclusive as possible – give all a chance of succeeding. o Try to involve each cadet in the lesson and give each one the chance for some success. o Pay attention to all of the cadets – not just those who are successful or are most engaged. o Have a sense of humour – but use it wisely. o Know their names and use them when addressing them. o Be quick to sense the feeling of the class and note when you have lost its attention – and do something about it

– eg a short break or a quick game.

C-3

o A little encouragement is worth a lot of correction. Give praise when it is due and develop a 100 ways to say "well done" (and remember to add their name)! Remember to reward effort not just results and never humiliate a cadet. o Reward commitment to learning. For example, make sure the cadets get their badges at the earliest opportunity after their star passes are confirmed. Try to get someone senior or a VIP to present the badges. o Avoid value judgments – leave any personal prejudices at home. o Treat each cadet as an individual o Invest time in learning about the cadets and their interests and backgrounds. Talk with them on an equal basis either as a group or as individuals. Recognize the importance to them of their families. o For those who may be struggling, slow things down, break the skills into smaller, more manageable chunks, make the training fun and reward effort, not just achievement.

Those are the ‘Dos’. Here are some ‘Don’t’s. Any of the following can kill the cadets’ interest:

A disinterested, bored approach

The instructor speaking for too long, especially lengthy explanations

An entire 30 minute period of being lectured to

A dull, monotone voice

Long, complicated words and phrases, unfamiliar terminology or adult, rather than teenage, vocabulary.

Unfamiliar military jargon or acronyms

Putting cadets down for trying

Being critical when giving feedback

A disrespectful attitude.

Sarcasm,

Humiliation

Unfair treatment

Bullying

A short temper

An air of superiority

Expecting too much too soon

Giving cadets too much to think about at one go

C-4

Be aware of the potential barriers to learning:

Distractions such as mobile phone communications & social networking.

Cadets being afraid of some of the activities or the environment.

New found interest in the opposite sex.

Other pastimes (computer games, sports, hobbies).

Peer group pressure.

Part time jobs.

School and college commitments.

External stresses.

Becoming bored with cadets.

For girls, sometimes a lack of female instructors/role models.

C-5

Annex D to

CFIT Handbook

EFFECTIVE ASSESSMENT

1. Your entire lesson would be a waste if your cadets knew nothing new at the end or were unable to perform the skill you were trying to teach them. The only way that you will know whether they have successfully achieved what you set out for them to be able to do is by assessment.

Planning the assessment of cadets

2. When you are planning your lesson, you will need to think about when and how you will assess how well the cadets are performing in relation to the aims and objectives you have set them.

3. You should certainly assess during the lesson, but on some occasions you may also need a separate period for formal assessment, eg in weapon handling, the instruction is separate from the formal Weapon Handling Test, however, informal assessment of how the cadets are doing with each of the aspects of handling the rifle is a critical part of the learning process.

4. Methods of assessing can include: a. Oral Questioning . Prepare a few questions to ask of the class to determine whether cadets have grasped the objectives you wanted them to achieve. When asking questions, use the ‘pose, pause, pick, praise’ technique:

Pose. Pose the question (eg “Name one of the rules in the Countryside Code..”)

Pause. Pause for a moment or two to let the cadets think.

Pick. Choose one of the cadets to answer the question. Do this carefully. This is not about trying to catch out, show up or embarrass any of the cadets. Try to give individuals a chance to answer correctly, whilst including all of the group to make sure that they have achieved the objective.

Praise. Give praise for correct answers. Give positive feedback and encouragement. Where answers are incorrecttry rewording the question or give a hint to help the cadet get the answer or give an encouraging response, eg:

“That was close – the answer was ……..” or

“That’s not quite it, can anyone else have a go….”, then go back after a few more questions and ask again,

Golden Rule: Never humiliate a cadet who has got something wrong. b. Practical Test . All practical subjects should be tested with a practical test – drill, turnout, map reading, first aid etc. c. Written Test. Use written tests sparingly. Not all cadets have good written skills –, true/false and multi-choice tick tests overcome the problems of requiring written answers.

You can read the questions out if cadets may have reading difficulties. Be aware that some cadets may have dyslexia, which is more difficult than simply having poor written communication skills. They may need to be assessed orally when the remainder are undertaking a written test. There may be occasions when you will want to mark written tests yourself, but for more informal assessment, consider the cadets swopping their papers round for marking.

D-1

d. Worksheet. These could include puzzles and games, like matching pairs, eg matching a list of map symbols with their names. e. Quizzes and Competitions.

These can be individual or team quizzes and competitions. If they are team events, you will need to observe who contributes and use follow up questioning or testing for those you have been unable to assess. f. Observation . You may, during a lesson be able to observe the cadets’ performance, for example in first aid, putting a casualty in the recovery position. As long as you have been able to observe each cadet putting another into the recovery position confidently and effectively, then you will not need separate testing. However, if cadets are not performing effectively, this gives you the opportunity to adapt the lesson to ensure that shortfalls are corrected, or move on more rapidly if cadets are sufficiently competent.

5. When planning assessments, you need to make sure that you are only asking the cadets to demonstrate knowledge and skills that they have actually been taught and had a chance to revise and practice. Wherever possible, practical skills, such as drill, skill at arms and navigation should be tested by practical assessments not through knowledge-based tests.

Assessing cadets

6. Encourage cadets to evaluate their own performance: a. Ask them how they feel they have done. b. Consider peer evaluation (ie the cadets assessing each other), which can range from marking each other’s tests or worksheets to telling the group about their observations of others’ performance. c. Suggest they write a little bit about their progress and how they feel about it in their notebooks.

7. Decide how you will capture the results of the assessment – if you are assessing informally, you might just make a few notes, however, for formal assessments, you may need to collect in and mark test papers or have a record sheet to write down results before, where necessary, capturing them on Westminster.

Giving feedback

8. Try always to give feedback on performance. Try to start by asking the cadet(s) how he/they think(s) he/they did, getting them to cover good points and areas for improvement). Where possible, try to do this with each cadet.

9. Feedback can take place throughout the lesson. It does not just have to follow a formal assessment. For example, during a drill lesson, correct cadets after each set of movements, eg.

“That was good marching; just remember to keep your arms straight and bring them up to shoulder height when you swing them forward.”

10. Keep feedback simple. Do not try to correct too many errors at once. Initially cadets may make many mistakes. They will not be able to remember or cope with your feedback if you try to correct everything at once. They will just become demoralised and believe they will never succeed.

Select just one or two of the most important mistakes to concentrate on first. Work on those until they are resolved, then work on more minor ones.

11. Feedback should: a. Give praise and encouragement , but not be ‘over the top’.

D-2

b. Explain shortfalls and how they should be corrected – youngsters want to be told how to correct mistakes, not to be shouted at or ignored.

12. Make the feedback: a. Timely – as soon as possible after the assessment, or at least in time for the cadet to rectify any shortfalls before the next time he needs the knowledge or skills. b. issues.

Honest - do not be overly critical, but do not shy away from addressing genuine c. Accurate – feedback must be correct. d. Constructive – feedback should never be negative. If a cadet needs to improve his performance then it should be presented as an area for improvement or development, not as a failure. e. Open - allow the cadet to ask clarification questions.

13. Try to confirm, for example by questioning or getting the cadet to perform the skill, that feedback has been understood.

D-3

Annex E to

CFIT Handbook

LESSON EVALUATION FORM

Lesson

Title

Star level/group

Ser

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10 of Plan

Student

Cadet

Area

Lesson Plan

Environment

(classroom/ training area etc)

Consideration of

Safety

Learning Aids

(eqpt, handouts/ worksheets)

Implementation

Communication

Assessment questions

Instructor –

Relationship

Motivation

Instructor

Description

Aims, objectives, choice and variety of activities, timings, content, order, flow

Layout, climate, light, distractions

Clear ID of hazards and risks; Effective control measures; safety briefing

Choice, design, effectiveness, sufficient

Class management, training method, intro, development, consolidation

Language, pace, voice, tone, body language, jargon, listening

Were objectives achieved - observation; questions; test; effective feedback

Addressed; answered clearly

Empathy, rapport, discipline, humour

Success, enjoyment, desire to learn

Date

Location

Successes Points for Improvement

E-1

11 General Comments

12

13

Best things about the lesson

Suggestion for improvement

Overall effectiveness of

Lesson

(1 - 10)

E-2