VAT - Afresp

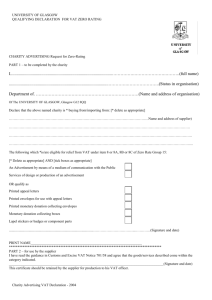

advertisement

VAT in federal countries: international experience Artur Swistak Fiscal Affairs Department International Monetary Fund, Washington Seminar: ICMS and the Future of the States Guarujá, Sao Paulo, Brazil, September 16-17, 2015 Views expressed in this presentation are of the author’s and should not be attributed to the IMF, its Executive Board, or its management. Outline • Principles of VAT: theory and practice – scope, method and basis • Decentralization of VAT – rate differentiation & revenue sharing • Regional VATs – issues and a handful of examples • EU experience with VAT harmonization – evolution, current solutions & proposals • Alternative VAT designs: – CVAT & VIVAT Let’s start with PRINCIPLES OF VAT VAT – the tax of 21st century • Almost unheard of 60 years ago; first introduced in France (1954) • Now 150+ countries have it; and its spread continues • Replaced distortive turnover and/or retail taxes • Excellent revenue raiser (ca. 25 percent of world’s tax revenue) • A ‘good tax’ if well designed and implemented simple, efficient, neutral Recipe for a “good” VAT: Basic principles • Objective: raise revenue! • Scope: – broad base: goods and services – minimum exemptions/reliefs – single positive rate • Imposition: – multiple stage tax (whole value chain covered) – invoice-credit method; refunds paid – destination basis • Practice differs widely across countries Weaknesses of VAT • Equity: – VAT a regressive tax • Administration: – need to pay refunds – prone to abuse (missing trader or carousel fraud) • Cross-border issues: – place of supply: where to tax? to whom benefits accrue? – VAT a national tax: how to design VAT in federations? how to share the tax base/revenue? how to avoid competition? how to cooperate? how to keep administrative/compliance costs in check? International experience with VAT in federations SubVAT national Standard VAT level Federal States Level Rate Argentina Provinces 21 National Mexico Australia States 10 National Micronesia Austria Lands 20 National Nepal Belgium Regions 21 National Nigeria Bosnia and Herzegovina Entities 17 National Pakistan Brazil States 18 Regional Russia Canada Provinces 5/10 Regional Saint Kitts and Nevis Comoros Islands None Somalia Ethiopia Regions 15 National Switzeralnd Germany Lands 19 National UAE India States 14 Regional USA Malaysia States None Venezuela Federal States SubVAT national Standard VAT level Level Rate States 16 National States None Zones 13 National States 5 National Provinces 17 National Republics 18 National Islands 17 National States None Cantones 8 National Emirates none None States none None States 12 National • Most of federations have national VATs, a few of these are decentralized, though • Only few operate regional VATs (Brazil, Canada, India) • Is VAT design an impediment to adoption by those who have none? What are the common VAT structures? Unitary State Federation/ Common market National VAT Regional VAT Uniform VAT Decentralized VAT Independent Harmonized Piggybacked Territorial rates Revenue Sharing Sub-national administration Individual Why VAT is mostly a national tax? • Constitutional setting (taxing power) • Common market and regional harmonization requirements (e.g. EU) • Policy choice due to: – ease of design – lower administrative effort – more efficient macroeconomic policy: • • • • less competition/higher productivity preference to transfers and development equalization national trade and other policies planning and forecasting Standard features of national VAT • Uniform central policy, usually no additional sub-national similar taxes or piggybacking • Single legislation and jurisprudence (even if regional nuances exist) • Single administration and enforcement (government tax offices) • Central government source of revenue (even if shared) National VAT does not have to be that uniform DECENTRALIZED VATS VAT Decentralization - overview • Countries have discretion in adopting VAT structure • Some federations avoid “problems” with sub-national VAT and “decentralize” it • Degree and scope of decentralization vary • Examples of decentralization include: – Rate differentiation/exclusions – Use of regional tax administrations – VAT revenue sharing/allocation – a viable option to regional VATs Decentralized VAT: rate differentiation • National VAT with reduced rates applied to specific regions/territories • Objective: regional development, redistribution, incentivizing some activities or avoiding competition • Examples of lower rates found both in federations and unitary states: – – – – Austria, Mexico in border regions, areas Spain in Canary Islands, Ceuta & Melilla Portugal in the Azores Peru (the Amazonia) • Examples of VAT exclusions in EU: – Finland (Aland Islands), Greece (Mount Athos), France (e.g. Mayotte), UK (Chanel Islands), Germany (Islands of Heligoland), Italy (e.g. Lake Lugano), and many others – treated as non-EU for VAT purposes Decentralized VAT: administrative arrangements • Regional tax authorities collect VAT on behalf of: – Federation, e.g.: • Mexico – apart from administering VAT states entitled to keep share of additional VAT (due to audits) • Quebec – the only province to collect federal GST – Unitary states (usually highly devolved), e.g.: • Spain (Basque Country and Navarre) • UK (Isle of Man) • Tanzania (Zanzibar) Decentralized VAT: revenue sharing • Revenue sharing found both in federations and unitary states (e.g. Morocco, Japan, Korea, UK) • National VAT revenue transferred directly to: – States (e.g. Australia, Germany, Austria, Nigeria) – Local governments (e.g. Belgium, Spain, also Germany, Austria, Nigeria) • Degree of allocation varies (and changes over time): – Total redistribution - Australia – Sharing - e.g. Germany (ca. 50 %), Spain (ca. 1/3), Austria (ca. ¼), Nigeria (65 %), Argentina (ca. 40 %) – In some federations national VAT is not shared at all (e.g. Switzerland, Canada’s federal VAT, Russia since 2001) Decentralized VAT: revenue allocation formulas • Types of allocation: – indirect (through grants, general transfers, e.g. Argentina) and direct (earmarking) – vertical and horizontal (or both) • Allocation keys established through: – prescribed percentages (e.g. Nigeria) – formulae (e.g. Australia) • Allocation bases: – – – – consumption (Spain, Japan, Korea, Isle of Man in UK, proposed for EU) transaction or “derivation” basis (China) population (Germany), School-aged children (Belgium) population + “relativity” (level of development, cost of providing services, fiscal capacity) (Australia) – poverty (Morocco) So how do regional VATs work? REGIONAL VATS Central issues in sub-national VAT design • Assure that regional VAT: – – – – – – – – respects fiscal autonomy of regions/states and accrues to them preserves VAT chain does not impede intra-state trade does not distort production and falls on consumption does not distort locational decision (competition) exhibits compliance symmetry is simple and not costly to comply with and administer provides proper incentives for VAT enforcement/collection by tax administration • Not a big challenge in “no border adjustment” setting if: – intra-state trade balance identical, and – full harmonization of base and rate in place • Unfortunately, this does not happen in practice; and… harmonization goes against the objective of fiscal autonomy Destination vs. origin basis • Destination basis: – superior economically but quite difficult to enforce – implemented through: • immediate zero-rating of sales and deferred payment on acquisition (e.g. EU, Canada) • deferred zero-rating and advance payment on intra-state aqusition (e.g. EEU) – does not immediately solve cross-border shopping (most of B2C supplies taxed on origin basis) • Origin basis: – easier administratively but distortive and not equitable revenue-wise – distortions tackled through: • lower/harmonized rates on intra-state transactions (imperfect!) • clearing house (concept not yet applied in practice, surrogate used by EU for MOSS) • deductions/refunds in country of origin (partially in EU, proposed as default measure in 1998) – revenue protected through numerous carve-outs and shift to destination basis for B2C transactions (widespread in EU) Different types of regional VATs • Canada – HST, piggybacked (dual VATs), harmonized, destination basis (zero-rating in Quebec) • Brazil – origin based ICMS, some harmonization with lower and harmonized rates on intra-state transactions • India – origin based state taxes (VAT-like); inter-state trade taxed with federal VAT • Economic blocs (no fiscal borders): – EU (single market) – separate VATs, fairly harmonized, destination/origin based, deferred payment, some elements of revenue sharing – EEU (common market) – coordinated, destination/origin based, zerorating upon VAT payment in country of acquisition • WEAMU – fairly harmonized VAT, plans to do away with borders VAT in Brazil - overview • A pioneer in the VAT world! • Two types of VAT (non-cascading sales tax): – Federal: Tax on manufactured production (IPI) • tax (excise) on select goods only, • significant limitation to deduction of credits • rates varying by category of goods (0-330%) – State: Tax on circulation of goods and services (ICMS) • distinct from IPI, with overlapping base, no piggybacking • Some degree of harmonization, independent administration • limited in scope: goods and select services (cross-border, inter-state and inter-municipal transportation and communication) • dual rates: intrastate and interstate (rates set by federation) • origin principle, no clearing used (equalization in “importing” state) • Plus municipal tax on services (ISS) – gross receipt, cascading VAT in Brazil - issues • No comprehensive, broad-based tax • Complex structure – three different taxes, little harmonization (even more so in practice, e.g. enforcement of “tax substitution” scheme) • High compliance and administrative costs • Pervasive distortions (cascading, tax exporting) • Inter-state tax competition • Revenue productivity undermined • Development objectives not met VAT in India -overview • No genuine VAT due to strict separation of taxing power: – – – – Union: production of goods, most services States: sales of goods, and few specific services Interstate trade: Central Sales Tax in origin state In practice: overlapping base for goods and cascading • Since ‘86 central “VAT” – Mod VAT CenVAT: – Replaced Union Excise Duty – Limited crediting mechanism (ModVAT), widened under CenVAT – Deferred deduction of input tax for capital goods, no deduction of other (state) taxes paid on inputs, beyond manufacturing level – Applied only at manufacturing level, widened over time – Numerous rates, different for goods and services • In 2005 central VAT supplemented with state VAT (pre-retail level) • Overall design: CenVAT, state VAT, plus CST VAT in India – planned reform (2016) • Dual VAT for all goods and services, replacing: – Central GST: current CenVAT (excise duty and service tax), – State GST: current VAT, entry tax, luxury tax and entertainment tax – Integrated GST: on interstate supply of goods and services • • • • Full crediting, no cross-crediting CGST and IGST collected by central tax administration SGST collected by state tax administration Interstate VAT charged in origin state and credited in destination state; revenue apportioned afterwards • Compensation for states losing revenue foreseen for 5 yrs. VAT in Canada (1) • Dual VAT: – Federal: GST at 5% applied throughout the country – Provincial: HST at 8-10% in most provinces, administered by federal tax administration – Some exceptions: • Quebec: GST+QST, both administered by Quebec tax administration • 3 provinces: GST+RST • Alberta: only GST • Design (in a nutshell): – Both GST & HST on destination basis – HST harmonized, largely piggybacked on GST but not fully, e.g.: • some limitation to deductions in QST • new housing taxed differently in all provinces • Books (taxed under GST), zero-rated under HST – Choice of HST rates left to provinces’ discretion VAT in Canada (2) • Important: Dual VAT administered by federal administration (except Quebec) • Inter-province trade and services taxed in province of origin basis, but credit taken in province of destination • Excess credits generated by HST may be offset against GST • No zero-rating (as in past); with QST as an exception • In practice HST an integrated national tax • Revenue shared among provinces: – Revenue from GST & HST collected by federation is pooled – Provinces’ shares in GST base are calculated on destination/consumption basis – This base is used for HST redistribution (by applying effective HST rate to the share of GST base) How does the VAT work in the EU? VAT IN THE EUROPEAN UNION A Brief History of VAT in EU (1) • 1962 – Neumark Report recommends VAT (with eventual adoption of origin principle for intra-EU trade) • 1970 – Introduction of VAT (First and Second Directive ‘67) – – – – – Applied in all member states; a prerequisite to EEC/EU’s membership Replacement of various gross sales taxes Objective: improve internal market by ‘de-taxing’ exports VAT not harmonized; early stage of coordination VATs differed significantly; countries had much leeway • 1970 – VAT to be part of EEC/EU’s “own resources” – 0.3 % of uniform VAT base (with caps and reduced call-up rates, e.g. Austria, Germany, Netherlands, Sweden) A Brief History of VAT in EU (2) • 1977 – VAT “harmonization” (Sixth Directive ‘77) – – – – Objective: adopting broadly identical VAT Minimum rate: 15 percent, reduced rates on select items Destination principle and border adjustments kept Cross-border refund system introduced (Eighth Directive ‘79) • Mid ‘80s – towards a single market, proposal to remove (costly) fiscal barriers – Origin principle proposed – to lower the cost of cross-border transactions – Clearing system for reallocation of VAT (otherwise Germany and Benelux the winners) – not accepted A Brief History of VAT in EU (3) • 1993 – transitional system adopted: – Fiscal borders removed, no tax controls – Two principles in place: • Destination principle for B2B transactions, • Origin principle for final consumers (B2C) but: – Distance sales, tax exempt legal entities (e.g. banks) and new means of transport – VIES and Fiscalis to reinforce cooperation and functioning of VAT • 1996 onwards – towards “definitive” system – Transitional system meant to apply until 1996 – No progress towards origin based VAT (though further proposals made, e.g. system of deduction in the country of origin proposed in 1998) – Focus on improvement of the transitional VAT - numerous policy documents and proposals made, various changes introduced Summary of VAT developments Further harmonization Extension of destination principle •Base •Rate •Administrative procedures • Place of supply rules • Special schemes • Exchange of information Improvements to enforcement • Mutual assistance/joint audits • Capacity building EU VAT – current structure • VATs levied by member states (no effective EU government): – • • • Obligatory, with harmonized structure (to large extent), coordinated implementation Broad-based consumption tax Operated largely on destination basis: – – • • • • 28 VAT national regimes, 28 distinct tax administrations intra-community trade (B2B) relying on deferred payment (reverse charging) cross-border supplies to consumers (B2C) relying on “forced” registration (deemed place of supply) No clearing mechanism for origin based taxation (most B2C supplies); No VAT transfers/remittance between states (exception: MOSS scheme since 2015) Catering well to single market idea, not perfectly though; High complexity due to: – – numerous schemes and exceptions need to register (or appoint tax representative) in many states Critical issues in EU’s VAT • Proper functioning of regional VATs in Europe depends much on: – degree of harmonization – rules on place of supply – implementation of destination principle – keeping complexity in check (compliance cost) – efficiency of tax administrations • Trade off between above objectives VAT harmonization in EU (1) • Single policy - EU legislations (e.g. directives) transposed to national tax systems; reinforced by European Court of Justice • Full harmonization not yet achieved: – numerous derogations, e.g. territorial , national, including parking rates, ad hoc derogations – discretion in choice of certain design features, e.g. some exemptions and thresholds (registration, distance sales, legal entities) – optional solutions, e.g. place of supply (effective use and enjoyment), special regimes (e.g. flat schemes) – some leeway in VAT administration (e.g. registration, guarantees, filing, refunds, etc.) • VAT rates not harmonized, only: – minimum standard rate of 15 percent (maximum is a political agreement) – number of reduced rates (reduced and super reduced) VAT harmonization in EU (2) • Lack of full harmonization impacts cross-border trade (hence functioning of single market) and revenues capacity of member states: – higher compliance costs, even if borders do not exist – cross-border shopping: exploitation of rate differences by: • final consumers, including non VAT entities • businesses – location for distance sales • Hence, adjustments to place of supply to alter origin base (by default applicable to B2C), e.g.: – – – – – Distance sales of goods, Means of transportation, Supplies of gas, electricity, telecommunication, etc. Digital services Transportation services Place of supply • A critical concept of VAT as it determines where supplies are taxed and which state gets VAT (cross-border trade or not) • In line with destination principle and nature of VAT it should be where goods/services are consumed in economic sense (directly or indirectly) • A tricky concept to define in practice, especially in case of services, (rendering, enjoyment, establishment of supplier or consumer), e.g.: – advertisement, entertainment, renovation, accounting, legal – assembly or installation (service or goods) – triangular supplies of goods • In general place of supply deemed to be where: – customer is established (B2B), or – supplier is established (B2C) • Numerous exceptions exist Intra-community acquisition of goods • Conditions: – supplier and buyer are VAT registered businesses – traded goods are transported across the border – it’s irrelevant: • where supplier and buyer are established, or • if they are different businesses/taxpayers • Place of taxation: – [standard] state of buyer’s VAT registration – [triangular] state of final arrival of goods • Exceptions - there is no ICA in case of (e.g.): • distance selling above threshold • acquisition of gas, heat, electricity • installation and assembly – In such case – registration in the state of acquisition required Supply of goods • In general (B2C) – where supplier is established • Specific rules: – where goods are located (immovable property, assembly/installation of goods) – where customer is located (distance sales above the threshold, gas, electricity, etc.) – where passenger vessel starts its journey (goods sold to passengers) • Such cross-border transactions: – require foreign company to register in the state of supply/taxation to charge local VAT – ICA can still be part of the transaction chain (e.g assembly/installation) • This increases cost of compliance but in line with implementation of destination principle Supply of services (general) • No concept of importation or intra-community acquisition of services • EU’s treatment: – not different from other countries, or – before 1993 as physical/fiscal borders irrelevant for services • Services taxed in the state/country where place of supply • For cross-border services reverse charge mechanism used • Place of supply depends on: – status of customer (B2B or B2C), and – nature of service (identified by EU due growing trade) • To ensure that VAT receipts better accrue to state of consumption several exceptions introduced over time Supply of services (specific) • For B2C services: – – – – Transport of goods (non-ICA): where service performed Repair/valuation of movable property: where service performed Car rental (long term): where customer resides Telecommunication, broadcasting, digital services: where customer resides • For B2C and B2B: – passenger transport: according to distance covered – services related to immovable property (e.g. hotel accommodation, construction): where the property is – Admission to cultural, sporting, entertainment etc. events: where the event take place – Restaurant and catering services: where services performed – Car rental (short term): where car is put at customer’s disposal Implementation of destination principle • Deferred payment (B2B) Simple workings, similar to import/export but with no border adjustment (Germany-France intra-community supply example): • Supplier charges zero-rate and issues VAT invoice with buyer’s VAT number (validated through VIES); then claims input VAT in Germany (deduction or refund); • Goods cross physical border with no tax control – no tax is paid at the entry to France • Buyer accounts for French VAT (at rate applicable in France) when goods are used in his production or sales - input tax, i.e. tax on intraEU acquisition, becomes a credit claimed in one return • Taxpayer’s registration in state of supply (mostly B2C) – French company registers in Germany to supply certain goods, e.g. distance sales, and services, e.g. telecommunication Challenges in VAT administration • VATs handled by national tax administrations, thus different: – traditions, enforcement tools, and overall capacity • Ease of interpretation and enforcement: – complexity of cross-border VATs – quality of national legislation (transposition of EU law and ECJ’s rulings) – direct application of EU’s directives – interactions of “not that uniform” national VATs • Exploitation of weaknesses in VAT design - fraud Common fraud in cross-border VAT • Standard evasion involves: – illegitimate refunds, – no accounting for VAT while charging it to customer and – no remittance of charged VAT, i.e. missing trader scheme disappearance of taxpayer before VAT is remitted (phony bankruptcies, bogus companies) • Cross-border fraud: – exploits the weakest element of VAT design: deferred payment – Two types: • acquisition fraud (missing trader scheme – first link in supply chain) • carousel fraud (missing trader + refunds – first and last link) – Commonly involves small goods of high value (e.g. mobile phones), also services (e.g. greenhouse gas emission allowances trade) • Tackled commonly through reverse charge mechanism and better enforcement/administrative cooperation Response to problems in VAT administration • VAT information exchange system (VIES) • Mutual assistance, joint actions (audits) • Improved IT systems and communication between tax administrations • Fiscalis program – cooperation of tax administrations (exchange of practices, networking, training) • Continuous improvements/changes to VAT system What are the possibilities for improvement of VAT design in federations? ALTERNATIVE VAT DESIGN So far experience points to the following solutions: • Joint VAT: – Federal but decentralized VAT with revenue sharing (most federal sates) • Separate VATs: – Origin basis with no clearing mechanism and offsetting (India) – Origin basis with no clearing mechanism but some form of equalization (Brazil) – Zero-rating and differed payment (as in EU, Quebec) – Deferred zero-rating and advance payment (EEU) • Dual VAT: – Origin basis with crediting against federal tax (dual harmonized VAT, as in Canada) Alternative solutions to sub-national VAT • Origin basis with clearing house mechanism (as proposed for EU) • Compensating VAT: CVAT or “little boat” (as proposed by Varsano) • Viable integrated VAT: VIVAT (as proposed by Keen and Smith) Compensating VAT (CVAT) • Requires dual VAT – federal and state level, with CVAT being an addition to federal VAT • Preserves destination base without break in VAT chain: – zero-rating under state VAT in “exporting” state (refunds) and anew standard taxation in “importing” state, with simultaneous – add-on of CVAT to standard federal VAT in “exporting” state (recovered in “importing” state) • Tax is carried between states in CVAT; reallocation required • Under such scheme CVAT rate at the average rate of state taxes (no room for competition and scope for fraud limited) • Compliance strategy not assured – need to distinguish between intra and inter state transactions; plus traders and non-traders • CVAT does not solve problem of cross-border shopping Viable Integrated VAT (VIVAT) • Integrated, i.e. single VAT with rate differentiation for: – intermediate trade (B2B) – single across federation – final sales (B2C) – set by states • Intermediate rate ideally lower than final rate (otherwise refunds needed at retail stage and VAT chain weakened) • No need to distinguish between intra and inter state trade (compliance symmetry) • Still need to distinguish between B2B and B2C (compliance asymmetry) • Preserves destination principle and provincial autonomy • Clearing mechanism needed; not a challenge if VAT administered by a single agency A numerical example Keen (2000), p. 8 Let’s compare… Rate autonomy Collection incentives Separate VATs Dual VATs Joint VAT CVAT VIVAT Yes Yes Possible Some Some Strong Strong Good Unknown Unknown Compliance symmetry No No Yes No Yes Need to identify destination state Yes No No Yes Low Moderate Higher? Need to distinguish types of purchasers* No No Depends on system No No Yes Yes Credit tracking Yes No No No Yes Excess credits Some Few No Some Yes Administrative capacity High Less Lower Moderate High Central administration No Some needed Probable** Probably Probably Need for single administration No Preferable Yes No No Need for central state cooperation No Yes Yes High Independent Independent Formula Administrative cost Revenue distribution Need for clearing of some credits Potential for interstate evasion Cross-border shopping a problem * Other than exempt ** Probable but not necessary Source: R. Bird (2013), adapted High No No No Yes Essentially independent Yes High Restricted No Restricted Restricted Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes For further reading… • • • • • • • • Bird R. (2013), Decentralizing Value Added Taxes in Federations and Common Markets, Bulletin for International Taxation, IBFD, pp. 655-72 Bizioli G and C. Sacchetto, eds. (2011), Tax Aspects of Fiscal Federalism. A Comparative Analysis, IBFD, Amsterdam Brederode van, R. and P. Gendron (2013), The Taxation of Cross-Border Interstate Sales in Federal or Common Markets, World Journal of VAT/GST, Law, 2:1, pp. 1-23 Cottarelli C. and M. Guerguil, eds. (2015), Designing a European Fiscal Union. Lessons from the experience of fiscal federations, Routledge, New York Keen M. (2000), VIVAT, CVAT and All That: New Forms of Value-Added Tax for Federal Systems, IMF Working Paper, WP/00/83, Perry V. (2012), International Experience in Implementing VATs in Federal Jurisdictions: A Summary, Tax Law Review, 63:623, pp. 623-38 Purohit M. (2002), Harmonizing Taxation of Interstate Trade under a Sub-National VAT – Lessons from International Experience, VAT Monitor, pp. 169-19 Varsano R. (2000), Sub-National Taxation and Treatment of Inter-State Trade in Brazil: Problems and Proposed Solutions, in: S. Burki and G. Peary (eds.), Decentralization and Accountibility of the Public Sector, World Bank, Washington Thank you aswistak@imf.org