A comparison of compulsory powers under new Queensland

advertisement

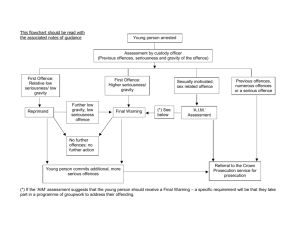

A comparison of compulsory powers under new Queensland legislation and in the UK The Inaugural Environmental Law Enforcement Conference – Thames Path 2011 Stuart Macnaughton, Partner Dated: 14 June 2011 Level 11 Central Plaza Two 66 Eagle Street Brisbane QLD 4000 Telephone 07 3233 8888 Fax 07 3229 9949 Offices Brisbane Newcastle Sydney GPO Box 1855 Brisbane QLD 4001 Australia ABN 42 721 345 951 www.mccullough.com.au Table of contents 1 Introduction ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 2 Enforcement options in Queensland -------------------------------------------------------------- 1 Sustainable Planning Act 2009 (Qld) 1 Environmental Protection Act 1994 (Qld) (EP Act) 2 General environmental duty 2 Investigation and enforcement 2 Recent changes 3 The new compulsion power 3 Notices 5 Which Court? 6 Magistrates Court 7 P&E Court 7 New Court Orders 7 Example 10 3 Practical issues ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------11 4 Parallel proceedings – criminal and civil --------------------------------------------------------11 5 Policy issue – Jurisdiction of P&E Court ---------------------------------------------------------12 6 Enforcement options in the UK -------------------------------------------------------------------12 7 General environmental duty 12 Compulsion powers 12 Corporate offenders 14 Notices 15 Court orders 15 Conclusion ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------16 11671697v1 A comparison of compulsory powers under new Queensland legislation and in the UK i A Comparison of Compulsory Powers under new Queensland legislation, and in the UK The Inaugural Environmental Law Enforcement Conference – Thames Path 2011 Stuart Macnaughton, Partner 1 Introduction 1.1 The purpose of this paper is to consider the compulsory powers of the Environmental Protection Agency (EP Agency) in Queensland against the background of the enforcement options available to the EP Agency, the venues for enforcement action available to the EP Agency, and the recent changes to the legislation and the effect of the changes. 1.2 I will also examine the compulsory powers available to the UK regulators under the Environmental Protection Act 1990 (UK), and discuss the extent to which those powers are consistent with the powers available to the Queensland EP Agency. 1 2 Enforcement options in Queensland Sustainable Planning Act 2009 (Qld) 2.1 The Sustainable Planning Act 2009 (Qld) (SPA) contains a number of offences relating to development and use of premises. Sections 574-583 set out a range of development offences including: (a) undertaking self-assessable development without complying with the code (section 574 SPA); (b) carrying out assessable development without a permit (section 578 SPA); (c) failing to comply with the terms of a development approval including a condition (section 580 SPA); and (d) carrying out prohibited development (section 581 SPA). 2.2 SPA also makes it an offence to fail to comply with an enforcement notice. 2 2.3 SPA did not significantly amend the offence provisions that existed under the Integrated Planning Act 1997 (Qld) although it created new offences to deal with the new categories of development it introduced. 1 The author does not profess to be an expert in the UK law, and others will have more detailed knowledge and experience in this area. The comparative analysis has been undertaken by referring to the source legislation and a limited range of cases to illustrate contrasts in comparison with the Queensland position. 2 s 594 SPA. 11671697v1 A comparison of compulsory powers under new Queensland legislation and in the UK 1 2.4 SPA provides for issuing show cause and enforcement notices. Under SPA, it is no longer generally a pre-requisite to issue a show cause notice as a first step. Instead, SPA allows the issuing body not to deliver a show cause notice where it reasonably considers it is not appropriate to do so in the circumstances. However, the practical effect of the provision has probably not significantly altered procedures for the majority of the run of the mill cases. 2.5 The receipt of an enforcement notice gives the recipient a right of appeal to the Planning and Environment Court or Building and Development Tribunal.3 The effect of an appeal is to stay the enforcement notice.4 2.6 The SPA provisions are relevant as environmental authorities operate as development approvals and conditions alike. Environmental Protection Act 1994 (Qld) (EP Act) General environmental duty 2.7 Queensland law imposes a general environmental duty on all persons not to cause environmental harm unless all reasonable and practicable measures are taken to reduce the harm.5 A person must also report material or serious environmental harm resulting from their activities unless it is specifically authorised under some form of licence or permit. Failure to comply without reasonable excuse is an offence, and the potential for self-incrimination is not a reasonable excuse.6 Investigation and enforcement 2.8 A number of investigation and enforcement powers exist under the EP Act. Prior to the EP Amendment Date, these included powers of authorised officers to: (a) require the provision of information relevant to the administration or enforcement of the EP Act;7 (b) enter premises with owner’s consent or a warrant, or during operating hours for premises with particular licenses or authorities;8 and (c) require a person to answer questions about a suspected offence or produce documents relevant to authorisations under the EP Act. 2.9 There are also powers to take action or direct others to assist or take action in cases where material or serious environmental harm has or might occur without intervention. 9 2.10 The EP Agency has power to issue clean up notices in certain circumstances. 2.11 There are a range of offence provisions in the EP Act for failing to assist or comply with an authorised officer in the exercise of their powers.10 It is also an offence to provide false or misleading information or documents.11 3 ss 473 and 533 SPA. s 474 of SPA. 5 s 319(1) EP Act. 6 s 320 EP Act. 7 s 451. 8 ss 452-455. 9 s 467. 10 ss 470-478. 11 ss 480-481. 4 11671697v1/S3 A comparison of compulsory powers under new Queensland legislation and in the UK 2 Recent changes 2.12 The EP Act was amended on 4 April 2011 (EP Amendment Date). These changes increased the scope of the enforcing agency’s investigation powers and expanded the range of Orders the Court can make in respect of environmental offences. 2.13 The powers of authorised officers were expanded by changes introduced on the EP Amendment Date. Now, an authorised officer can: (a) require the provision of information relevant to the administration or enforcement of the EP Act;12 (b) enter land to search or test for the source of a contaminant.13 Previously, section 453 allowed entry to land once it was established that environmental harm had been caused, in order to confirm the source of the contaminant which had caused the harm. Under the recent changes, entry may be made on the reasonable belief that environmental harm has been caused; (c) require a person to answer questions about a suspected offence or produce documents relevant to authorisations under the EP Act; 14 and (d) require attendance at a specific time and place in order to answers to questions.15 2.14 This last new power has also introduced a new offence for an individual (i.e. not a corporation) to fail to attend or fail to answer questions. Significantly, this potentially erodes the privilege against self-incrimination for directors and officers of corporations, who can be compelled to attend and answer questions as an individual to adduce evidence which can be used against the corporate entity of which they are an employee or director. 2.15 Corporations do not enjoy the common law privilege from self-incrimination,16 and the Queensland regime imposes a liability on executive officers for the actions of their companies unless they can prove they took all reasonable steps to achieve compliance or were otherwise not in a position to influence the actions of the corporation.17 The new compulsion power 2.16 The new power to compel a person to attend and answer questions does not make the same distinction as the New South Wales legislation, which specifically allows the New South Wales authority to require a person to attend and give answers, or to require a corporation to nominate a representative to attend and give answers which will bind the company. 2.17 Instead, the section reads as follows: ‘465 Power to require answers to questions (1) This section applies if an authorised person suspects, on reasonable grounds, that— (a) 12 13 14 15 16 17 an offence against this Act has happened; and s 451. ss 452-455. ss 465-466. ss 465(2)(b). Environmental Protection Authority v Caltex Refining Co Pty Ltd (1993) 178 CLR 447. s 493 EP Act. 11671697v1/S3 A comparison of compulsory powers under new Queensland legislation and in the UK 3 (b) (2) a person may be able to give information about the offence. The authorised person may— (a) require the person to answer a question about the suspected offence; or (b) by written notice given to the person, require the person to attend a stated reasonable place at a stated reasonable time, to answer questions about the suspected offence. (3) When making the requirement, the authorised person must warn the person it is an offence to fail to comply with the requirement, unless the person has a reasonable excuse. (4) A notice given under subsection (2)(b) must— (a) identify the suspected offence; and (b) state that the authorised person believes the person may be able to give information about the suspected offence; and (c) include the warning required to be given under subsection (3).’ 2.18 It is hard to guess how quickly this new power will be taken up and absorbed into government processes, and how widely used and applied. However, it is possible to see that requiring a potential defendant to attend an interview and answer questions could be come to be seen as a precursor to bringing proceedings that should be taken by “a reasonable prosecutor” 18 or a model litigant. Certainly, the failure to offer the opportunity to attend an interview has been the subject of criticism against authorities seeking to prosecute, particularly where Executive Officers are being pursued. 2.19 The Land and Environment Court gave the New South Wales provision consideration in the case of Southon v Beaumont.19 2.20 In that case the Applicant sought to have the statutory notice to attend and answer questions set aside, and further sought declarations that the notice could be complied with by providing questions and answers in writing. 2.21 The Applicant asserted two grounds on which the notice was invalid: firstly, that attendance was not reasonably required to enable questions to be put and answered (because that could be done in writing); and secondly that the notice did not assert statutory limitations including that it was issued by an authorised officer who has a reasonable suspicion of information they required. 2.22 The Land and Environment Court declined to make the orders sought by the Applicant, and awarded costs against him. 2.23 This new power will have significant practical affects in terms of the way in which people and corporations being investigated deal with the authority. Now the EP Agency may compel attendance at a place and time provided it is reasonable, and compel the answering of questions. The answering of the questions and the evidence thereby created can be used against the company for whom the individual works or is a director to secure a conviction. Once a company is convicted of an offence, an Executive Officer is also potentially liable for the offence of failing to ensure the corporation complied with its obligations. 18 19 see Fairfield City Council v El Nachar [2009] NSWLEC 154, at paragraphs 12-14. [2008] NSWLEC 12 11671697v1/S3 A comparison of compulsory powers under new Queensland legislation and in the UK 4 2.24 An Executive Officer is defined under the EP Act as: ‘Executive Officer’, of a corporation, means – (a) if the corporation is the Commonwealth or a State – a chief executive of a department of government or a person who is concerned with, or takes part in, the management of a department of government, whatever the person’s position is called; or (b) if the corporation is a local government - (c) (i) the chief executive officer of the local government; or (ii) a person who is concerned with, or takes part in, the local government’s management, whatever the person’s position is called; or if paragraphs (a) and (b) do not apply – a person who is – (i) a member of the governing body of the corporation; or (ii) concerned with or takes part in, the corporation’s management; whatever the person’s position is called and whether or not the person is a director of the corporation. 2.25 Section 493 of the EP Act requires Executive Officers of a corporation to ensure the corporation complies with the Act20, and provides that the evidence the corporation has committed an offence is evidence that each of the Executive Officers committed the offence of failing to ensure the corporation has complied with the Act.21 2.26 The defence provision for an Executive Officer 22 requires the Executive Officer to prove (either): (a) if the Executive Officer was in the position to influence the conduct of the corporation in relation to the offence – the Officer took all reasonable steps to ensure that the corporation complied with the provision; or (b) the Executive Officer was not in a position to influence the conduct of the corporation in relation to the offence. 2.27 Both limbs of the defence carry a heavy factual and evidentiary burden. 2.28 Clearly there is now greater scope for Executive Officers to be found guilty on an offence against section 493 of the EP Act based on evidence obtained from compulsorily required answers provided at a compulsorily attended interview. 2.29 The Queensland regime also prescribes significantly higher penalties be imposed on conviction of a corporation compared to an individual. The maximum penalty for a corporation is five times that of an individual. Notices 2.30 20 21 22 For the minor offence of littering from a vehicle, the Queensland EP Act allows for service of a Penalty Infringement Notice (PIN).23 PINs are used for other non-indictable offences in ss 491(1). ss 493(3). ss 493(4). 11671697v1/S3 A comparison of compulsory powers under new Queensland legislation and in the UK 5 Queensland, such as parking violations and minor fair trading breaches. A PIN will state the details of the offence and invite the offender to pay a specified fine or else contest the issue of the notice.24 Issuing a PIN does not prevent bringing or continuing a prosecution for the offence in the Magistrates Court.25 2.31 In some circumstances, the EP Agency may issue a clean up notice requiring a person or corporation to: (a) prevent or minimise contamination; (b) rehabilitate the environment; and/or (c) assess and report on harm caused by an incident. 26 2.32 It is an offence to fail to comply with a clean up notice. However, a recipient has a defence if they can show that the notice was issued to the wrong recipient, can establish that all reasonable measures had been taken to prevent the incident in question or show that the incident occurred as the result of a natural disaster or terrorist attack. 27 2.33 For very specific offences, being environmental nuisance, contravention of noise standards and depositing contaminants in water, a direction notice can be issued. These notices require the recipient to remedy the contravention.28 It is an offence not to comply without reasonable excuse.29 2.34 In cases of more serious environmental offences, particularly failure to comply with the general environmental duty or specific approvals or permits, an environmental protection order can be issued following consideration of legislated criteria. 30 2.35 The order may require the cessation of an activity, prohibit the commencement of an activity or limit the time during which an activity may be carried out. It may also require stated actions to be taken within a set timeframe.31 Environmental Protection Orders can be a means to secure compliance with a range of conditions and other authorities, as well as the general environmental duty.32 It is an offence not to comply with such an order.33 2.36 It is an offence to contravene an environmental protection order, and wilful contravention carries a higher maximum penalty (fine) and could involve a sentence of imprisonment. 34 However, the issuing of an Environmental Protection Order is a decision which can be appealed,35 and there can be difficulties in proving the required consideration was given. Which Court? 2.37 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 Offences against the EP Act are generally prosecuted in the Magistrates Court. However, proceedings to stop or prevent an offence can be brought in the Planning and Environment Court s 440G EP Act. s 16 State Penalties and Enforcement Act 1999 (Qld). s 17 State Penalties and Enforcement Act 1999 (Qld). ss 363G-363H EP Act. s 363I EP Act. S 363B EP Act. s 363E EP Act. s 358 EP Act. s 360 EP Act. s 358 EP Act. s 361 EP Act. s 361 EP Act. Schedule 2, EP Act. 11671697v1/S3 A comparison of compulsory powers under new Queensland legislation and in the UK 6 (P&E Court).36 A general requirement for the P&E Court to make Orders is that it is satisfied that environmental harm has been or is likely to be caused. 37 Magistrates Court 2.38 Prosecution proceedings can be started in the Magistrates Court. 2.39 The prosecution proceedings are determined on the criminal standard and can be started either for failure to comply with the Enforcement Notice, or against the underlying development offence. P&E Court 2.40 Enforcement proceedings can be brought in the P&E Court, including by individuals in some cases, without the issue of an enforcement notice. 38 2.41 There can be advantages to commencing enforcement proceedings in the P&E Court rather than the Magistrates Court. It can be used if time limitation issues have arisen for criminal proceedings, and the onus of proof is on the balance of probabilities. Additionally, P&E Court judges are generally more familiar with SPA and the EP Act than Magistrates. 2.42 The P&E Court has powers to make enforcement orders, including interim enforcement orders subject to the applicant’s undertaking regarding costs. However, prior to the EP Amendment Date there was little scope to make other orders.39 New Court Orders 2.43 The power of the Magistrates Court to make orders on conviction which are additional to payment of fines and recovery of costs for rehabilitation undertaken by government authorities was significantly expanded on the EP Amendment Date. 2.44 The previous section 502 read: 36 37 38 39 “502 Court may order payment of compensation etc. (1) This section applies if, in a proceeding for an offence against this Act, the court finds the defendant has caused environmental harm by a contravention of this Act that constitutes an offence. (2) The court may order the defendant to do either or both of the following— (a) pay to persons who, because of the contravention, have suffered loss of income, loss or damage to property or incurred costs or expenses in preventing or minimising, or attempting to prevent or minimise, loss or damage, an amount of compensation it considers appropriate for the loss or damage suffered or the costs and expenses incurred; (b) take stated action to rehabilitate or restore the environment because of the contravention. s 505. s 505(2)(a)(i). s 601 SPA. ss 509-510. 11671697v1/S3 A comparison of compulsory powers under new Queensland legislation and in the UK 7 2.45 (3) An order under subsection (2) is in addition to the imposition of a penalty and any other order under this Act. (4) This section does not limit the court’s powers under the Penalties and Sentences Act 1992 or any other law.” As of the EP Amendment Date, section 502 now reads: “502 Court may make particular orders (1) This sections applies if, in a proceeding for an offence against this Act— (2) (3) (a) the court finds the defendant has caused environmental harm by a contravention of this Act that constitutes an offence; or (b) the court finds the defendant has committed an offence against any of the following— (i) section 426 (ERA for mining activity); (ii) section 426A (ERA for mining activity); (iii) section 427 (registered operators only may conduct a chapter 4 activity); (iv) section 430 (contravening and environmental authority); (v) section 435 (contravening and development condition); (vi) section 435A (contravening a standard environmental condition); (vii) section 440ZG (depositing prescribed water contaminants in waters). The court may, on application by the prosecution, make 1 or more of the following orders against the defendant— (a) a rehabilitation or restoration order; (b) a public benefit order; (c) an education order; (d) a monetary benefit order; (e) a notification order. Subsection (4) applies if the court finds that, because of the act or omission constituting the offence, another person has— (a) suffered loss of income; or (b) suffered a reduction in the value of, or damage to, property; or (c) incurred costs or expenses in replacing or repairing property, or in preventing or minimising, or attempting to prevent or minimise, a loss, reduction or damage mentioned in paragraph (a) or (b). 11671697v1/S3 A comparison of compulsory powers under new Queensland legislation and in the UK 8 (4) In addition to any order the court makes under subsection (2), the court may, on application by the prosecution, order the defendant to do either or both of the following— (a) pay to the other person an amount of compensation the court considers appropriate for the loss, reduction or damage suffered, or costs or expenses incurred; (b) take stated remedial action the court considers appropriate. (5) An order under this subsection must state the time within which the order must be complied with. (6) This section does not limit the court’s powers under the Penalties and Sentences Act 1992 or any other law. (7) In this section— education order means an order requiring the person against whom it is made to conduct a stated advertising or education campaign to promote compliance with this Act. monetary benefit order means an order requiring the person against whom it is made to pay an amount representing any financial or other benefit the person has received because of the act or omission constituting the offence in relation to which the order is made. Example of a monetary benefit order— If a defendant is found to have carried out an environmentally relevant activity without an environmental authority, the court may order the defendant to pay the administering authority an amount equal to the annual fees for the period for which the activity was carried out without an environmental authority. notification order means an order requiring the person against whom it is made to notify in a stated way a person, or class of persons, of— (a) the act or omission constituting the offence in relation to which the order is made; and (b) other stated information about the act or omission. Examples of ways the notification may be required to be given to particular persons— by publishing the notification in the person’s annual report by giving the notification to persons affected by the act or omission public benefit order means an order requiring the person against whom it is made to carry out a stated project to restore or enhance the environment in a public place or for the public benefit. rehabilitation or restoration order means an order requiring the person against whom it is made to take stated action to rehabilitate or restore the environment that was adversely affected because of the act or omission constituting the offence in relation to which the order is made.” 11671697v1/S3 A comparison of compulsory powers under new Queensland legislation and in the UK 9 2.46 The requirement for the Court to make a finding that environmental harm was actually caused by a defendant to enliven section 502 has been removed with respect to a number of offences, including with respect to carrying out environmentally relevant activities and contravening environmental licences or development conditions. So long as the Court finds the offence was committed, the prosecution will no longer need to prove environmental harm before applying to the Court to make a section 502 order. 2.47 The Court’s powers to make awards to persons who suffer loss or damage because of a contravention has been expanded so that remedial action may be ordered as an alternative or addition to compensation. 2.48 The types of orders which can be made against a defendant, as well as or in addition to imposition of a penalty, have been increased and now include: (a) rehabilitation or restoration orders, requiring action to counter adverse environmental affects of the offence; (b) a public benefit order, requiring some sort of work to be undertaken in a public place or otherwise for the public benefit; (c) an education order, requiring the offender to conduct an advertising campaign promoting compliance with the EP Act; (d) a monetary benefit order, requiring account to be made for any benefit gained by committing the offence. A similar provision exists in Western Australian legislation.40 Essentially, the prosecution can seek an additional financial penalty be paid to the administering authority; and (e) a notification order, requiring the convicted to publish in a certain way particular details about the offence committed. This type of deterrent has been popular with the Australian Securities and Investment Commission and the New South Wales Environmental Protection Authority in their enforcement processes. However the examples contained in the EP Act indicate that the legislature may not intend for such orders to involve particularly wide circulation. Example 2.49 The New South Wales EPA prosecuted Werris Creek Coal Pty Ltd in 2009 for a breach of condition of an environmental licence. The incident in question occurred in 2007 and involved the actions of a contractor. Werris Creek Coal Pty Ltd pleaded guilty to the strict liability offence and was fined $49,000. 2.50 The money was allocated the local Quipolly Dam Regeneration Project. The Judge found that the breach of licence was not foreseeable, that minor or no environmental harm was caused and Werris Creek Coal is only responsible because it is the licence holder. 2.51 Werris Creek Coal Pty Ltd was also ordered to pay the prosecutor’s costs of $34,700 and put a notice in the Sydney Morning Herald and Australian Financial Review to publicise the offence to deter other offenders. The text of the advertisement appears as Annexure A to this paper. Notably, the advertising costs associated with the notice were in the order of around $14,000 (on top of the fine and costs orders). 40 Environmental Protection Act 1986 (WA), s 99Z. 11671697v1/S3 A comparison of compulsory powers under new Queensland legislation and in the UK 10 3 Practical issues 3.1 A significant factor in any kind of enforcement action for authorities is to ensure they have the correct delegations and appointments and authorisations in place. Because the powers under SPA and the EP Act are largely exercisable only by authorised officers, and upon the authority being satisfied about certain matters, without the correct procedure being followed there is no power to act. 3.2 A major consideration for authorities seeking to enforce development and environmental laws will always be costs. Partly for this reason, informal and out-of-court enforcement options may often seem to be an easy initial step. Moreover, evidence of having taken this type of action can be of assistance in a prosecution or declaratory proceeding. 3.3 Costs are also a factor in deciding whether to take enforcement action in the P&E Court. For one thing, there is currently no scope for having the offender fined; even though the costs of proceeding may be greater than the costs of prosecuting in Magistrates Court. Additionally, interim relief often will not be granted by the Court without some kind of financial assurance as undertaking from the authority. 3.4 In an environmental context, a significant hurdle prior to the EP Amendment Date was the requirement of the enforcing authority to prove up environmental harm, or the very real threat of it. However as a result of amendments to section 502, that is at least in part addressed for certain offences. 4 Parallel proceedings – criminal and civil 4.1 It is increasingly becoming the modus operandi of the Agency for concurrent proceedings to be commenced. 4.2 The decision of the P&E Court in Environmental Protection Agency v Hudson Timber Products Ltd & Ors41 makes it clear that a stay cannot be obtained in respect of the civil proceedings of the P&E Court to overcome potential prejudice in the criminal proceedings arising out of the same facts and circumstances. 4.3 In that case, His Honour Judge Rackemann said ‘(t)he existence of parallel proceedings does not prevent this court from entertaining proceedings for enforcement orders or interim enforcement orders’.42 In making that decision His Honour referred to then section 510(2) of the EP Act which authorises the P&E Court to make an enforcement order ‘whether or not there has been a prosecution for the offence’. The same proviso is now contained in section 507(2). 4.4 This decision was later referred to in Booth v Yardley43 in stating that it was not improper to have civil enforcement proceedings being heard regarding the same facts which form the basis of a criminal proceeding which is on foot. 4.5 The effect of the Hudson Timber Products decision and the statutory compulsion contained in the recent change to section 465 of the EP Act would substantially shift the weight of evidence gathering in favour of the Agency, by requiring the Respondent (defendant) to either elect to put material on in the P&E Court to defend the enforcement proceedings (or resist without putting on any material), or simply consent to orders and avoid the putting on of material in those proceedings. Any material put on by a Respondent in the P&E Court proceedings would deliver a substantial forensic advantage to the prosecution in its case preparation and presentation. 41 42 43 [2005] QPEC 069. Environmental Protection Agency v Hudson Timber Products Ltd & Ors [2005] QPEC 069 at paragraph 6. [2007] QPELR 205 at 212. 11671697v1/S3 A comparison of compulsory powers under new Queensland legislation and in the UK 11 5 Policy issue – Jurisdiction of P&E Court 5.1 There is a body of thinking that efficiency of process and justice might best be served by enlarging the jurisdiction of the P&E Court to take on the prosecutorial proceedings presently dealt with in the Magistrates Court. That the District Court Judges (who comprise the P&E Court) have jurisdiction in relation to indictable offences, and regularly deal with the concepts contained under the SPA and the EP Act all militate in favour of the P&E Court assuming their jurisdictions. 5.2 Recent experience44 indicates that extremely complex factual situations involving multiple ‘eras’ of planning and environmental legislation are well dealt with by the P&E Court. 5.3 Were the P&E Court to have its jurisdiction enlarged to include the prosecution matters currently determined by the Magistrates Court, it would bring it in line in some respects with the New South Wales system in the Land and Environment Court where there are a number of different classes of litigation determined before the Court. 5.4 The changes brought about by the recent changes to the EP Act on the EP Amendment Date, particularly the enlarging of the powers of the Magistrates Court to make orders on conviction, only serve to reinforce the opportunity for change. 6 Enforcement options in the UK General environmental duty 6.1 The Environmental Protection Act 1990 (UK) (UK Act) imposes a similar obligation to Queensland’s general environmental duty on holders of all authorisations to carry on a prescribed process, in implying a general condition that authorisation holders will use the best available techniques (subject to excessive cost) to prevent pollution and environmental harm.45 6.2 Interestingly, in respect of statutory nuisances, the UK Act imposes an obligation on local governments to make inspections to ensure statutory nuisances within their area are detected, and to investigate complaints made to it about statutory nuisances.46 The Court has held that, where the local government is satisfied on the balance of probabilities that a statutory nuisance existed, it was under an unqualified duty to issue an abatement notice and no discretion in this respect was available to it.47 That is in direct distinction to the Queensland position. Compulsion powers 6.3 Two regimes for acquiring information for environmental investigations are provided under UK legislation, namely disclosure notices and investigative entry and compulsory powers. 6.4 Firstly, UK enforcement agencies may compel the disclosure of information from persons (and other authorities) in relation to different Parts of the UK Act. This includes under the integrated pollution control provisions, the waste on land provisions and the provisions dealing with genetically modified organisms (GMOs).48 The compulsion power is not available with respect to littering or statutory nuisance. 44 45 46 47 48 Elsafty Enterprises Pty Ltd & Anor v Gold Coast City Council [2011] QCA 084 s 7(4) UK Act. s 79 (1) UK Act. R v Carrick District Council (1996) 95 LGR 621. ss 19, 71 and 116 respectively, of the UK Act. 11671697v1/S3 A comparison of compulsory powers under new Queensland legislation and in the UK 12 6.5 The powers are available to different authorities for each Part in discharging their functions. Although not expressed in identical terms, the effect of each power appears to be generally the same. 6.6 The section 19(2) power (with respect to integrated pollution control) reads: “For the purposes of the discharge of their respective functions under this Part, the following authorities... may, by notice in writing served on any person, require that person to furnish to the authority such information which the authority reasonably considers that it needs as is specified in the notice, in such form and within such period following services of the notice as is so specified”. 6.7 The section 71(2) power (waste on land) reads: “For the purpose of the discharge of their respective functions under this Part [the relevant authorities] may, by notice in writing served on him, require any person to furnish such information specific in the notice as the ... authority ... reasonably considers he or it needs in such form and within such period following services of the notice as is so specified”. 6.8 The section 116 power (GMOs) reads: “For the purposes of the discharge of his functions under this Part, the Secretary of State may, by notice in writing served on any person who appears to him— (a) to be involved in the importation, acquisition, keeping, release or marketing of genetically modified organisms; or (b) to be about to become, or to have been, involved in any of those activities; require that person to furnish such relevant information available to him as is specified in the notice, in such form and within such period following service of the notice as is so specified ”. 6.9 The section goes on to define relevant information as information pertaining to any aspect of the activities specified.49 6.10 Each Part makes it an offence not to comply with such a notice without reasonable excuse. 6.11 The House of Lords has made it clear that these provisions, conferred for the purpose of obtaining evidence and serving a broad public purpose, may not be avoided on the grounds of privilege from self-incrimination.50 6.12 In that case, the appellant had been convicted with failing to comply with a notice issued under section 71(2) of the UK Act. The notice was issued in December 2005. Proceedings for failing to comply with the notice were instituted in February 2006, separate from proceedings issued in June 1996 for offences relating to waste management to which the accused pled guilty. Lord Hoffman noted that the notice in question requested only factual information and did not seek any admissions.51 6.13 The Court noted the broad public purpose and held that the privilege of self-incrimination could not be relied upon to avoid questioning although a trial judge would retain the discretion to exclude evidence on the grounds of privilege. 49 50 51 s 116(2) UK Act. R v Hertfordshire County Council & Ors [2000] 2 A.C. 412. Ibid at 426. 11671697v1/S3 A comparison of compulsory powers under new Queensland legislation and in the UK 13 6.14 This decision might be questionable in light of, but has not been expressly overruled by, the European Court of Human Rights in Shannon v United Kingdom.52 One of the grounds of challenge to the issue of the notice in the Hertfordshire appeal was the Human Rights Convention. 6.15 The subsequent decision of Shannon concerned the power of a financial investigator to request an interview while making inquiries in relation to proceeds of crime. The Court concluded that the Convention had been violated by requiring the appellant to attend an interview regarding circumstance which had already given rise to charges being laid against him. 53 However, the Court also noted in its discussion that the issue of self-incrimination arises without the need for proceedings to be brought.54 6.16 Secondly, the Environment Act 1995 (UK) allows an authorised person to conduct investigations and examinations to enable the agency to carry out its obligations. 55 These powers include authority to: (a) enter any premises they believe necessary to enter at any reasonable time, or in an emergency (with some restrictions in relation to residential premises); 56 (b) require a person they believe able to provide information to answer questions and sign a declaration as to the accuracy of their answers; 57 and (c) to require the production of records necessary to be seen for the purposes of an examination or investigation.58 6.17 The Environment Act 1995 (UK) specifically provides that information obtained under section 108(4)(j) examination or answering of questions can not be used in evidence in proceedings against the person it was obtained from.59 This is in stark contrast to the Queensland position, particularly where the person is an Executive Officer. 6.18 In addition, documents which are covered by legal professional privilege do not have to be produced to an authorised person.60 Corporate offenders 6.19 Section 157 of the UK Act deals with offence committed by companies and provides: “(1) Where an offence under any provision of this Act committed by a body corporate is proved to have been committed with the consent or connivance of, or to have been attributable to any neglect on the part of, any director, manager, secretary or other similar officer of the body corporate or a person who was purporting to act in any such capacity, he as well as the body corporate shall be guilty of that offence and shall be liable to be proceeded against and punished accordingly”. 6.20 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Subsection (2) goes on to provide that, for a company managed by its shareholders, the above will apply to actions of a shareholder as if they were a director. Shannon v. the United Kingdom, no. 6563/03, European Court of Human Rights, 4 October 2005 Ibid at 41. Ibid at 40. s 108 Environment Act 1995 (UK). s 108(4)(a) Environment Act 1995 (UK). s 108(4)(j) Environment Act 1995 (UK). s 108(4)(k) Environment Act 1995 (UK). s 108(12) Environment Act 1995 (UK). s 108(13) Environment Act 1995 (UK). 11671697v1/S3 A comparison of compulsory powers under new Queensland legislation and in the UK 14 6.21 Like the Queensland regime, the UK Act specifically makes allowance for a corporation and its officers to both be convicted of the same offence. However, the UK Act requires a ‘deliberative act’ fault element to make out the charge whereas the Queensland regime only considers the individual’s conduct by reference to defences. In addition, the UK Act does not prescribe different penalties for corporations to that for individuals. Notices 6.22 The integrated pollution control provisions of the UK Act (which are administered by local governments in the case of air pollution only) allow the issue of enforcement notices only for the contravention or likely contravention of a condition of any authorisation to carry out a prescribe process.61 6.23 Similarly to a Queensland notice, the enforcement notices are require to state specific items of the enforcing authority’s beliefs and provide for certain actions to be undertaken with in a stated timeframe.62 6.24 The same Part of the UK Act allows for the issuing of prohibition notices where the enforcing authority believes there is an imminent risk of serious pollution of the environment. 63 Unlike an enforcement notice, the action complained of in a prohibition need not be the subject of a condition of an authorisation. 6.25 However, like an enforcement notice issued under the Queensland Planning Act, the decision to issue both the UK enforcement notices and prohibition notices is subject to judicial review.64 Bringing such an action does not have the effect of suspending the notice.65 6.26 In respect of statutory nuisance, local authorities have power to issue abatement notices. 66 A person who is served with an abatement notice and fails to comply commits an offence. 67 The local authority is entitled to take steps to remedy the nuisance and recover same as a charge against the property.68 6.27 Numerous other offences under the UK Act do not have provisions allowing for them to be dealt with by means of issuing a notice and must rather proceed by way of prosecution. Court orders 6.28 The UK Act provides maximum penalties for various offences. Like the Queensland regime, the penalties vary depending on whether the matter is dealt with as a summary prosecution or on indictment. Interestingly, the maximum penalty for summary offences in Scotland appears to generally be double that which applies in England and Wales.69 6.29 Provision is made in the UK Act for the Courts to deal with enforcement matters where the issuing of a notice affords ‘ineffectual remedy’.70 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 s 13 UK Act. s 13(2) UK Act. section 14(1) UK Act. S 15(2) UK Act. s 15(9) UK Act. s 80(1) UK Act. s 80(4) UK Act. ss 81-81A UK Act. see, for example, the two versions of s 23(2) in the UK Act. s 24 UK Act. 11671697v1/S3 A comparison of compulsory powers under new Queensland legislation and in the UK 15 6.30 Specific powers are granted to the Court to order the remedying of matters which constitutes an offence on conviction in numerous circumstances. 71 6.31 In addition, provision has been made for the enforcing authorities to seek to recover investigation and enforcement costs upon conviction.72 There is also scope to seek the clean up costs associated with remediation undertaken by an authority as damages. 73 7 Conclusion 7.1 As would be expected, there are significant similarities between the environmental protection regimes in place in the UK and Queensland. 7.2 At present, the Queensland laws place harsher penalties on corporate offenders and give wider scope for the Court, on successful prosecution, to make orders which go beyond merely imposing a fine and costs order on an environmental offender. 7.3 One difference is in the structure of the legislation. The UK Act creates separate parts for various areas of environmental protection, and each contains its own provisions for investigatory powers and its own offence provisions. In contrast, Queensland legislation deals with much of the regime for different areas in legislative policy. The investigation and prosecution provisions are contained within a single separate section of the EP Act. Contact details Writer: Direct line: Email: 71 72 73 Stuart Macnaughton 07 3233 8869 smacnaughton@mccullough.com.au ss 26, 120 UK Act. s 33A UK Act. s 33B UK Act. 11671697v1/S3 A comparison of compulsory powers under new Queensland legislation and in the UK 16 Disclaimer This paper covers legal and technical issues in a general way. It is not designed to express opinions on specific cases. This paper is intended for information purposes only and should not be regarded as legal advice. Further advice should be obtained before taking action on any issue dealt with in this publication. 11671697v1/S3 A comparison of compulsory powers under new Queensland legislation and in the UK 17 Annexure Example of notification Prosecution of Werris Creek Coal Pty Limited for Breach of Environmental Licence On 31 July 2009, the Land and Environment Court of New South Wales found Werris Creek Coal Pty Limited (ACN 107 169 102) guilty of an offence against the Protection of the Environment Operations Act 1997, as the holder of Environmental Protection Licence No 12290. Werris Creek Coal Pty Limited pleaded guilty to the charge and the Court found that, among other things: 1 On 16 July 2007 and continuing until 17 July 2007 it committed the strict liability offence against section 64 (1) of the POEO Act, in that a condition of the Licence was contravened. 2 The Licenced premises are about 4 kilometres south of the town of Werris Creek, near Tamworth. 3 The concentration of total suspended solids (TSS) in water sampled at what was storage dam 7 (SD7) at the time when sampled on 16 & 17 July 2007 exceeded the specified 100 percentile concentration limit of 59 milligrams per litre. 4 Environmental harm was minor but not zero. Werris Creek Coal Pty Limited was ordered to pay a penalty of $49,000.00 to fund part of the Liverpool Plains Shire Council Quipolly Dam Regeneration and Biodiversity Project . Werris Creek Coal Pty Limited was also ordered to pay the Environmental Protection Authority’s legal costs, including investigation costs and expenses of $34,700.00. Werris Creek Coal Pty Limited was prosecuted by the EPA, a part of the Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water. This notice is placed by order of the Land and Environment Court and is paid for the defendant Werris Creek Coal Pty Limited. 11671697v1 A comparison of compulsory powers under new Queensland legislation and in the UK 18