File - Tess Pauline Adamonis

advertisement

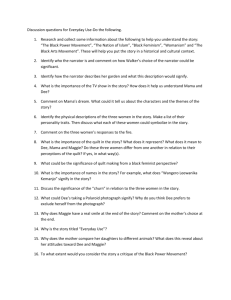

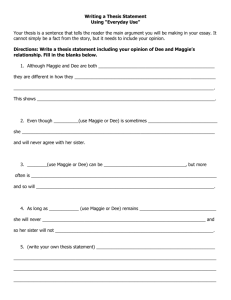

Adamonis 1 Tess Adamonis O’Conner EN360 12/20/2013 Resist the Dominant There are many cases in history where more advanced cultures will take over less dominant ones. The country where we live today was founded by men who were able to claim the land because they were more technologically advanced than the natives were. Since this has happened so often in history, many authors find it easy to write about a dominant culture overtaking others. In literature, this theory is known as postcolonial theory. Usually these stories are found when authors are writing slave narratives or any other history text and they are not usually found in fictional short stories. In the case of the American Short Stories, quite a few are written through this theory. Some of the more prominent ones are “Rappaccini’s Daughter” by Nathaniel Hawthorne, “The Yellow Wall-Paper” by Charlotte Gilman, and “Everyday Use” by Alice Walker. Each of these stories has the common aspects of postcolonial theory by their way of having a group of characters or a single character making another character feeling inferior and having a dominant power over them because of it. Nathaniel Hawthorne’s short story, “Rappaccini’s Daughter” takes place in Padua, Italy. The reader meets Giovanni Guasconti who has comes to Padua to pursue an education. His room overlooks a beautiful garden. The garden belongs to a famous doctor who takes the plants from his garden and turns them into medicines. His name was Signor Giacomo Rappaccini. One day Adamonis 2 he sees Rappaccini working in his garden. He examines each plant with no emotion. As he nears a purple plant, he puts on a mask, but finding the task of tending the plant to be too dangerous, he calls for his daughter, Beatrice. Giovanni finds her as strikingly beautiful as the plants around her. She begins to tend to the poisonous plan with much more care than her father would have given it. Later on, Giovanni comes to learn more about Doctor Rappaccini. Doctor Rappaccini is a brilliant scientist who cares more for science than for humankind itself. As he watch Beatrice from his window he see her pluck one of the blossoms from the purple shrub. As a few drops of moisture from the plant fall upon a passing lizard it dies immediately and later the same thing happens to an insect when Beatrice seemingly breathes upon it. Beatrice seems unsurprised at the events and carries on until she sees Giovanni. He has just seen these events happen before his eyes and he is not sure whether to be amazed or scared. After these events, Giovanni does everything in his power to avoid looking out the window at the garden. He is not sure what to think of his feelings for Beatrice. One day while he is out he runs into Baglioni, a professor of medicine and Giovanni’s father’s old friend and Rappaccini himself. Giovanni gets the hint that the Rappaccini might be planning something for him and breaks away from the pair and returns to his home. On his way home, Giovanni is stopped by Lisabetta, an old woman who lead him to the garden’s secret entryway. For a moment, he is worried that he might be part of the doctor’s experiment, but he continued anyway. Inside the garden, Giovanni finally meets Beatrice. Walking through the garden, they stop at the purple plant. Giovanni extends his hand to pluck one of its blossoms, like he had seen Beatrice due days earlier but Beatrice grasps his hand and flings it away from the plant, exclaiming that it is “fatal”. When Giovanni awoke the next day, his hand had a purple outline of her fingers. Giovanni began visiting Beatrice as much as possible. One day he is visited by Baglioni, who says there is smell of a strange perfume in Adamonis 3 Giovanni’s room. Baglioni tells Giovanni a story of an Indian prince who sent a woman as a present to Alexander the Great. This woman was beautiful, but had a deadly secret – she had been nourished with poison since birth. In the end, she became poisonous and her embrace would bring death. Baglioni tells Giovanni that Beatrice also had this secret. Of course, Giovanni is unwilling to accept this information and refuses to believe him. Baglioni then gives Giovanni a vial with an antidote, which could cure Beatrice of her father’s work. With this new information in mind, Giovanni realizes that over time he has become poisonous like Beatrice. He confronts Beatrice about everything and she reveals knew of her fate as well as his. Giovanni curses her for making him the same was as her. Beatrice is gravely upset by this and swears ignorance. Although Giovanni comes to believe, her, his words had hurt her deeply. Giovanni believes he can still save her and he gives her the antidote, which she willingly drinks. The poison in her body had become part of her life. The antidote succeeded not in saving her but in killing her. Baglioni, knowing this truth, was looking on from the window. Katalin Kállay author of the article, “Envying One’s Garden: a Touch of Rappaccini’s Philanthropy,” and many other authors, compare this story with the bible story of Adam and Eve. The garden is Eden itself, while Beatrice, Giovanni, and Rappaccini play the roles of God, Adam, and Eve. Rappaccini could be seen as God because he is the true maker of the garden. Interestingly enough the roles are reversed for Adam and Eve, seeing as Beatrice was the first being that was created she is seen as Adam and Giovanni is Eve. Baglioni is the serpent that makes everything worse at every possible turn. Baglioni is of course jealous of Rappaccini’s stunning work in his garden and he wants nothing more than to see him fail. “Baglioni unexpectedly appears every now and then- and seemingly unaware of his unwanted presence, he provides Giovanni with his paternal warnings in verbose sentences” (Kállay 331). The antidote Adamonis 4 that Baglioni gives Giovanni is the representation of the apple. In the end, Beatrice is the cost of charting into unwanted territory. Baglioni is the cog that messed everything up. “Had he been spying up there all through the scene awaiting for the foreknown result of his fatal antidote? That would at last put an end to his life-absorbing, irrational envy of the garden...” (Kállay 332). Kállay also talks about Beatrice and how most readers are unable to determine whether she is evil or not. “When Hawthorne’s wife asked him whether Beatrice was to be a demon or an angel, ‘I have no idea!’ was Hawthorne’s reply, spoken with some emotion” (Kállay 328). Hawthorne makes Beatrice into a character that seems very innocent and pure for someone that is so poisonous she is contagious. This “might convince the reader that she is free of all evil” (Kállay 328) but in the end she is still killing Giovanni slowly and also making him poisonous. In Morton Ross’s article, “What Happened in Rappaccini’s Daughter,” Ross talks a lot about how “the work of the story is to dramatize, at length and in great detail, the process by which Giovanni Guasconti comes to a judgment of Beatrice Rappaccini” (337). Beatrice has grown up inside the walls of the garden, does not know of what the outside world truly contains, and is one of the most innocent people that Giovanni has ever met. Yet he is still easily convinced by Baglioni that Beatrice is a bad person. Baglioni “plans to create a situation which will answer unmistakably the question of whether or not Beatrice’s presence is lethal to other life” (Ross 342). Giovanni takes the bait and is twisted with distress over this newfound information. Of course, Baglioni is doing this on purpose to create a rift in Rappaccini’s garden. If he can get Giovanni to throw off the balance of the garden Baglioni will be able to get a step ahead of Rappaccini. Baglioni gives Giovanni an antidote that is supposed to heal Beatrice of the poison in her body. However, Baglioni knows that the poison in her body is now helping keep her alive but does not give Giovanni this information. Giovanni and Beatrice have an argument Adamonis 5 and she ends up drinking the antidote but because her body is nourished on poison, she ends up dying. “The narrator by fiat has simply insisted that a preoccupation with Beatrice’s lethal exterior must five ways to knowledge that the real Beatrice is an angel” (Ross 343). This is how Baglioni is able to beat Rappaccini at his own game. Rappaccini was using Giovanni, as a pawn in an experiment, most likely he was trying to see if a healthy person would become poisonous after being in Beatrice’s presences for long periods of time. In the end, Rappaccini had to sacrifice his daughter to science to try to keep his role in the dominant culture around him. In Charlotte Gilman’s short story, “The Yellow Wallpaper” the reader follows the narrator as she begins her journal. It starts with the narrator writing of greatness of the house and grounds her husband has taken her to for their summer vacation. She discusses leads her illness that she is suffering from. She is suffering from nervous depression. She then writes of her marriage to her husband john and how he makes light of her illness even though he is also her doctor. She does not think he takes her own thoughts and concerns into account either. He husband has said that she is supposed to do nothing active, especially no working or writing. The narrator believes that she should do the opposite and that activities and work would help her in the end. This is why she has begun the journal that she must keep secret. She then begins describing her surroundings. Most of her descriptions are normal except for some odd things around her room, such as there being bars on the window. She then goes into great detail describing the wallpaper of the room. “The color is repellent, almost revolting; a smouldering unclean yellow, strangely faded by the slow-turning sunlight” (Gilman 137). The narrator becomes good at hiding her journal and hiding her true thoughts from John. She will always write about things that she wants or something that john has done to make her angry but then she will always go back to the wallpaper. The wallpaper begins to work its way into every writing. Adamonis 6 She has told john about the wallpaper and he begins to worry about her more. She describes her bedroom once again saying that it must have been a nursery for children, or a gymnasium at another point. She writes of how the paper is torn in places near her bed or has just worn off the walls in other places. Soon she is visited by another person, Jennie, John’s sister, who is also caring for the narrator. Other than the occasional visits from John and Jennie, the narrator is alone most of the time. She writes of how fond she had become of the wallpaper. As her obsession grows, the pattern of the wallpaper becomes clearer. It begins to resemble a woman that seems to be stuck in the paper. Unsurprisingly, the wallpaper soon is all the narrator can think or talk about. It takes over her mind to the point where she thinks that the women stuck in the wallpaper is actually caged inside of it. She keeps these thoughts a secret in her journal away from the eyes of her husband not wanting him to know about the woman. John thinks that once she beings to hide her thoughts of the wallpaper that she is actually improving when she is not. One night the narrator resolves to destroy the paper once and for all, peeling much of it off during the night. The next day she manages to be alone and tears down even more of the paper in order to free the trapped woman, whom she sees struggling from inside the pattern. In the end when john breaks into her locked room he sees the situation unfold before him and in horror and shock, he faints. The narrator continues her business stepping over her husband’s body when she needs to. The narrator struggles with her mental stability throughout the entire story. According to Beverly Hume, author of “Gilman’s ‘Interminable Grotesque’: The Narrator of ‘The Yellow Wallpaper,’” the narrator “details a struggle both with and against herself, one that results not only in her madness, but also in an elevated comprehension of that madness” (477). The narrator and her husband are complete opposites. “John is mechanistic, rigid, predictable, and sexist” Adamonis 7 (Hume 478), while the narrator is very fluid and completely unpredictable which is the reason she is able to hide her journal and her mental instability from her husband with ease. “When John is finally made aware of the severity of his wife’s ‘disorder,’ he reacts by ‘fainting,’ altering his conventional role as a soothing, masculine figure to that of a stereotypically weak nineteenthcentury female” (Hume 478). This is the main point in the story that the narrator is finally able to claim the superiority that she has been seeking over her husband. She has been hiding her true feelings from her husband, worried that he would not listen to her because all facts pointed to him doing just that. She keeps her thoughts on the wallpaper to herself because when she did express her opinions, John merely laughed and went about his business. Hume says, he does not “take her anxiety about the wallpaper seriously, and when she frantically expresses a desire to move downstairs, he persists in his laughter, calling her a ‘blessed little goose’” (478). In the end, most of the narrator’s mental instability comes from the fact that her husband brushed off his wife every time she spoke. It is completely probable that if he had stopped and gave his wife his full attention for five minutes she might not have been over taken by madness. Her husband told her not to write but the narrator turned to writing all her thoughts in her secret journal because it was the only way for her to vent. Her husband never bothered to ask what was going through her mind and neither did Jennie. The narrator was taken over by madness because she was thought to be inferior and thus everyone avoided her. The wallpaper in the room grasps the attention of the narrator as her instability increases. In the article, “The Reading Habit and “The Yellow Wallpaper” Barbara Hochman writes, “Once she [the narrator] becomes engrossed in the wallpaper, however, her desire to escape diminishes and then disappears” (95). The wallpaper is something that the narrator needs to figure out before she can better. It’s like the saying “the first step to recovery is admitting you have a problem,” Adamonis 8 but in this case the narrators first step to recovery is finding the answer to the wallpaper. Sadly, it drives her mad before she finds the solution. “The narrator grows increasingly absorbed in the paper and intensely possessive about it: ‘There are things in that paper that nobody knows but me or ever will,’ she insists” (Hume 95). Her obsession with the paper also stems from her need to be superior over something in her life. Her husband makes her feel like a lesser human being because of her illness. He acts as if he is vastly superior because of his full health and the fact that the narrator needs him much more than he needs her. If the narrator feels superior over the woman inside the wallpaper, she is able to get some balance back into her life. “Her efforts to ‘follow’ the pattern are repeatedly frustrated, but her desire to do so is a recurrent- in fact, a pervasive- emphasis in the story” (Hume 97). She was so determined to figure out what she saw in the paper that it gave her a drive to find the solution. “This story line centers upon a figure that takes on human features, motivations, and finally a specifically human shape” (Hume 97). It can be seen that the narrator feels superior to the woman in the wallpaper even though they are on in the same. Once the narrator “frees” the woman from the wallpaper, she has technically lost her ability to become superior because they can now be seen as equal. The narrator and the woman in the paper are equal due to the fact that they are now both “free” from the wallpaper. “Everyday Use” by Alice Walker is a short story of a family of three African American women in the 1970s, Mama, the narrator and her two daughters Maggie and Dee. Dee is coming for a visit to Mama and Maggie’s home. Dee has had a very different relationship with her mom than Maggie has. Dee went to school in Augusta and has climbed the social ladder much higher than Maggie has or Mama ever will. Maggie lives at home and is always very nervous and selfconscious of her scars and burn marks. She is going to marry a man that is just good enough to make her happy later on in life. Maggie and Dee do not have that close of a relationship to the Adamonis 9 point that when Dee arrives Mama has to grip Maggie’s arm to prevent her from running back into the house. Dee emerges from the car with her boyfriend, Hakim-a-barber, whom neither Mama nor Maggie knew was coming. Mama knew from the second she saw Dee that she had changed. Dee does not treat her visit as a way to catch up with her mom and sister but more of a way to figure out where her roots came from. She takes many pictures of Mama and Maggie in front of their house and ends up taking some of the family’s belongings with her later on. Nevertheless, before that happened Dee told her mother that she had changed her name to Wangero Leewanika Kemanjo to protest being named after the people who have oppressed her. This was the red flag that told Mama that Dee really had changed. Mama tries to convince Dee that her came was special. Dee named after her Aunt Dicie, who was named after their Grandma Dee, who bore the name of her mother as well. However, this did not matter to Dee because she did not want to be tied down with a name that reminded her of who she used to be. After dinner, Dee starts in on the things she wants from their home for her own. She takes items such as the butter churner, which she wants to turn into a centerpiece even though Mama still uses it to this day. One item that Dee has her eye on are the quilts that Mama kept in a trunk in her room. Dee wants the quilts to hang up so they can have decorative use in her home, but Mama does not want that. Mama suggests that Dee take other quilts, but Dee insists, wanting the ones handstitched by her grandmother. Mama reveals that she had promised Maggie the quilts. Dee gasps, arguing that Maggie will not appreciate the quilts and is not smart enough to preserve them. Dee thinks that using the quilts for everyday use is a tragedy for such beautiful things. However, Mama hopes that Maggie does, indeed, designate the quilts for everyday use and even though Maggie tells her mother that it’s all right Mama gives the quilts to Maggie and tells Dee to take others. Adamonis 10 Throughout “Everyday Use”, an underlying theme that is present is the knowledge of one’s heritage. Heritage can be seen as one of two things, an object that is passed down or inherited, or a tradition that is passed down. According to David Cowart, author of the article, “Heritage and Deracination in Walker’s ‘Everyday Use,’” Dee, from now on referred to as Wangero, uses her heritage as a stepping-stone of how far she has come. “Wangero’s desire is to have a record of how far she has come” (Cowart 175). Donna Haisty Winchell says, “She makes the mistake of believing one’s heritage is something that one puts on display if and when such a display is fashionable” (Cowart 175). This is the difference between Wangero and her family. Mama and Maggie easily see heritage as what is around them. Their heritage stems from their past and is not always a tangible object. Wangero’s original name Dee is an example of this. Dee was a name that had been passed down for generations. Until Wangero climbed the social ladder this name was perfectly acceptable, but soon she became tired of it. Wangero said, “I couldn't bear it any longer, being named after the people who oppress me” (Walker, 187). Wangero is becoming someone entirely different. “She now styles and dresses herself according to the dictates of a faddish Africanism and thereby demonstrates a cultural Catch- 22: an American who attempts to become an African succeeds only in becoming a phony” (Cowart 172). Everything about Wangero, her clothes, her personality, and even how she acts, is trying to say she’s something else if not something better, but she is not. This also brings up the question of who are the people she is talking about that are oppressing her. From the way she makes it sound, Wangero seems to believe that her heritage is oppressing her from having a better life. Her heritage is what has made her who she is today but none of that matters to her anymore. “Wangero’s flirtation with Africa is only the latest in a series of attempts to achieve racial and cultural autonomy, attempts that prove misguided insofar as they promote an erosion of all that is Adamonis 11 most real- and valuable- in African American experience” (Cowart 172). Wangero needs to find a culture to identify with. She left behind her heritage and everything she learned from it to become a new person. When she cannot fully accept the values of the new heritage, she has found she tries to come back to what she used to know. However, she can no longer identify with her old heritage as anything other than what she used to be. Heritage is a big part of who a person is and if they do not embrace it, they could lose sight of what it really means. In the end, Wangero could never be Dee again because she tried to leave that life behind. She cannot identify with either culture because she does not know which she actually belongs to. In Gail Keating’s article, “Alice Walker: In Praise of Maternal Heritage,” she writes about how Walker writes of women quite a bit. “All too often women’s accomplishments have been viewed as inferior since, traditionally, they have been judged according to male standards. Walker, however, acknowledges the great contributions women have made to our culture and traces the power of women through her own matrilineage” (Keating 26). When Keating talks about “Everyday Use,” she talks about how different Dee and Maggie are as women. Dee is assertive and will take what she wants and leave without a trace. Since Dee has traveled and climbed the social ladder, she no longer thinks that her heritage is below her. “In a very condescending way, Dee, now that she has made her way in the world, appreciates the beauty of the ‘art’ of her maternal heritage” (Keating 28). She finds joy in the little things that are from her childhood that she used to hate. For example, Mama offered Dee the exact same quilts that she wanted to take now when Dee left for college. However, at the time Dee found them “oldfashioned” and “out of style” (Walker 190). Maggie is very different from her sister. She is quite shy, quiet, and reserved. She is not as open as her sister is and likes simplicity just like her Adamonis 12 mama. Dee does not understand her sister. Her only argument against her mama as to why Maggie should not have the quilts is that, “Maggie would put them on the bed and in five years they'd be in rags. Less than that!” (Walker 190). Dee used the term Everyday Use as if quilts were not supposed to be used for that reason. “But the mother understands what Dee, even though she feel superior to Maggie, will never be able to understand: Maggie, as backward as she is, has found a way to express her creative spirit in the same way generation of women before her have done” (Keating 29). Maggie will never forget her heritage the way Dee has or struggle with her ability to identify with a culture because of what her mother has taught her. When Dee leaves, she tells Maggie, “You ought to try to make something of yourself, too, Maggie. It is really a new day for us. But from the way you and Mama still live you'd never know it.” What Dee does not realize is that what Maggie has learned from mama is more valuable than anything Dee has ever learned because it connects her to something. She is able to understand her heritage and where she has come from. Dee will never have that because she is imitating what she wants to be and not who she really is. In the end, Maggie is superior to Dee in ways that Dee could never come close to. Dee could learn a thing or two from her sister but will always be too proud to admit that she is wrong. Each of the stories that have been discussed are from completely different eras and are about completely different things. However, they all have the ability to have a single theory in common. Postcolonial theory is the “attempt to understand people from different cultures in terms of an important experience they all had in common: colonial domination by a superior European military force” (Tyson 245). In other words, “Rappaccini’s Daughter,” “Everyday Use,” and “The Yellow Wall-Paper” all have a common experience of a character or group of Adamonis 13 characters being dominated by another. The main characters that were victims of being the less dominant groups were Giovanni, the narrator from “The Yellow Wall-Paper,” and Dee. Postcolonial theory is very different from other theories because it not only explores human experience but it also “gives us the tools to explore how all of these factors- as well as ethnicity, religion, and other cultural factors that influence human experience- work together in creating the ways in which we view ourselves and our world” (Tyson 245). There are a few basic concepts that go along with postcolonial theory such as colonialist ideology, the colonial subject, and anticolonialist resistance. To start off, colonialist ideology is based on the colonizer’s belief that they are superior to the colonized (Tyson 248). In “The Yellow Wall-paper,” the narrator is seen as the colonized because her husband is the colonizer. When the narrator’s husband takes over making her decisions for her, she starts to become part of the less dominant culture. She listens to him even though she does not want to because she thinks he is right. She knows if she did not listen to him and play by his rules that she would not be able to get the things that she wants in the end. Because of her deteriorating mental state, the narrator is seen as a completely different person from her husband, John, and his sister, Jennie. As she worsens, both her husband and Jennie begin “othering” the narrator. A colonialist ideology term, othering is when someone is “judging those who are different as inferior, as somehow less than human” (Tyson 248). The colonizers embody themselves as the right form of how people should look, act, and dress. When there are people who are different from that form, they see them as beneath them. John is everything a good husband should be. He has a steady job as a doctor, he is married to a woman he cares about very much, and he is there for her when she needs him. The narrator is none of these things, especially because she has to be kept locked up in her bedroom. Since John and Jennie Adamonis 14 need to take care of her, since she is unable to take care of herself, they do not see her on the same level as them. This is because through the eyes of john and Jennie, the narrator is a subaltern, or a person that is seen as inferior because of their race, class, gender, religion, or any other cultural factors and therefore occupies the bottom rungs of the social ladder (Tyson 249). While at first it is not a big deal to be seen as a subaltern, soon it takes a toll on the person who is inferior. If there is a group of subalterns sometimes it is easier to band together against the dominant group but it is the ones that are alone that end up losing the battle. The narrator in this case will end up losing this battle because she has no one who can help her learn that she is more than what they see her as. Nevertheless, in the end the narrator will become a colonial subject just as many have in the past before her. To become a colonial subject, one must first be a subaltern. “Because there is enormous pressure on subalterns to believe that they are inferior, it should not be surprising that many of them wind up believing just that” (Tyson 249), thus turning them into colonial subjects. In “Everyday Use” Dee ends up as a colonial subject. From what is learned about Dee from the past, she believed she was inferior because of the fact that she was African American and where she was brought up. Society was telling her that she was inferior and in order for Dee to truly be a colonial subject, she needed to believe that she was indeed inferior. Dee could have changed herself for the better but instead decided to try to become part of the society that shunned her in the first place. Now, “One can be oppressed by colonialist ideology economically, politically, and socially without being a colonial subject as long as one maintains as awareness that colonialist ideology is unjust and that people who belong to the dominant Adamonis 15 culture are not naturally superior. In other words one is a colonial subject only when one’s consciousness is colonized” (Tyson 249). Dee is in fact a colonial subject because she thinks that being like the dominant culture will make her into a better person. She does this again when she beings to have a colonized consciousness about following African traditions. Her mimicry, “the imitation, by a subaltern, of the dress, speech, behavior, or lifestyle of members of the dominant culture,” (Tyson 249) of African traditions is seen firsthand when Dee visit Mama and Maggie. In her dress alone, Mama is able to tell that Dee, who soon tells her she changed her name to Wangero, has change greatly. Wangero wears a dress that flows down to the ground, even though the weather is very hot, and the colors are described as “so loud it hurts my eyes” (Walker 187) by Mama along with “yellows and oranges enough to throw back the light of the sun” (187). She was also adorned with jewelry such as “Earrings gold, too, and hanging down to her shoulders” (187) and “bracelets dangling and making noises when she moves her arm up” (187). For the time along with the culture that Dee is mimicking, Dee is very up and coming with the times and it proves that she is trying to make a point that she has moved on from her old life. The problem with Dee leaving behind her old culture is that if she ever wishes to return to it she could not. If for some reason Dee was rejected by the African culture Dee would suffer from unhomeliness or “the feeling of having no stable cultural identity” (Tyson 250). Dee has gone through so many changes in culture around her throughout her life due to her feeling inferior in her own culture. Dee will keep changing cultures because she will never be able to truly accept a culture that does not except her completely. With every culture that is overpowered by another, there is a group of people who will do anything to keep their culture alive. Anticolonialist resistance is “the effort to rid one’s land Adamonis 16 and/or one’s culture of colonial domination” (Tyson 250). In some cases, anticolonialist resistance can be in the form of violent attacks upon the dominant group while in others it is just a well-organized group of people bringing attention to the problem at hand. In the case of the story, “Rappaccini’s Daughter” anticolonialist resistance can be seen at the hand of professor Baglioni. Baglioni gives Giovanni an antidote that is supposed to heal Beatrice of the poison in her body. However, Baglioni knows that the poison in her body is now helping keep her alive but does not give Giovanni this information. This is Baglioni’s attempt at taking down Rappaccini’s domination. Rappaccini is more knowledgeable in the science of plants in ways that Baglioni could never be. Everyone else had been wowed by Rappaccini and his work but Baglioni just wanted to be on the same level as Rappaccini. Baglioni put up a great deal of psychological resistance, managing to keep his mind free of the ideology that he is inferior (Tyson 251), and it is able to fuel him to taking down Rappaccini. He never meant to kill Beatrice but he had “triumph mixed with horror” (Hawthorne 191) as he watched on the spectacle that he had created. Each of these stories can be read with a postcolonial perspective because there is always a group of people that think they are better than others are. The only hope that the seemingly inferior groups can have is that they stick together enough to create some sort of anticolonialist resistance. When too many people become subalterns it is hard to keep that culture alive and that is exactly what the dominant culture wants. They want to make the inferior feel so incredibly low that it forces them to believe that they are not important. In the end, the dominant culture will win because most subalterns will become colonial subjects. Postcolonial theory can teach others to “understand human experience as a combination of complex cultural forces operating in each of us” (Tyson 245). In this case working together is always better than working alone. Adamonis 17 There are many cases in literature where more advanced cultures will take over less advanced ones. It is survival of the fittest. Postcolonial theory can be found in many stories nowadays because it is so common for less advanced cultures to try and adapt to be more like the dominant. In “Rappaccini’s Daughter” Baglioni chose to bring down Rappaccini in order for them to become more equal, therefore making Rappaccini less dominant. In “The Yellow WallPaper”, the narrator fought against listening to her husband’s advice because she knew better. In “Everyday Use,” Dee gave into society’s view of her inferiority and therefore gave into her role as a colonial subject thus giving the dominant culture another win in their war with the inferior. Each of these stories had one thing in common; each character did everything in their power to defend their title. The dominant would do almost anything to stay the best. Rappaccini practically killed his daughter for the good of science. The inferior will do anything to keep from being washed away by the dominants. The narrator continued writing in her secret journal even though it was forbidden. The war rages on between the two and it will never truly be over until everyone can be seen as equal. Adamonis 18 Works Cited Cowart, David. "Heritage and Deracination in Walker's 'Everyday Use'." Studies In Short Fiction 33.2 (1996): 171-184. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 16 Dec. 2013. Garvey, Ellen Gruber. "Making Hay Of The Yellow Wallpaper: 'The Boveopathic Sanatorium' Proposes A New Remedy For Neurasthenia." Studies In American Humor 3.6 (1999): 4959. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 19 Dec. 2013. Gilman, Charlotte Perkins. “The Yellow Wall-Paper.” The New England Magazine. January, 1892. Gorelick, Risa P. "Go Crazy, Girl: Breaking The Silence In 'The Yellow Wallpaper' Through Acts Of Reading And Writing By Re-Examining Nineteenth-Century Rest Cures Under A Television Talk Show Paradigm." Louisiana English Journal, New Series 4.1 (1997): 70-75. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 16 Dec. 2013. Hawthorne, Nathaniel. “Rappaccini’s Daughter.” Mosses from the Old Manse and Other Stories. New York: Wiley and Putman, 1846. Hochman, Barbara. "The Reading Habit And 'The Yellow Wallpaper'." American Literature: A Journal Of Literary History, Criticism, And Bibliography 74.1 (2002): 89-110. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 19 Dec. 2013. Hume, Beverly A. "Gilman's `Interminable Grotesque': The Narrator.." Studies In Short Fiction 28.4 (1991): 477. Academic Search Premier. Web. 17 Dec. 2013. Adamonis 19 Kállay, Katalin G. "Envying One's Garden: A Touch Of Rappaccini's Philanthropy." Zeitschrift Für Anglistik Und Amerikanistik: A Quarterly Of Language, Literature And Culture 48.4 (2000): 326-333. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 16 Dec. 2013. Keating, Gail. "Alice Walker: In Praise Of Maternal Heritage." Literary Griot: International Journal Of Black Expressive Cultural Studies 6.1 (1994): 26-37. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 16 Dec. 2013. Ross, Morton L. "What Happens In 'Rappaccini's Daughter'." American Literature: A Journal Of Literary History, Criticism, And Bibliography 43.3 (1971): 336-345. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 17 Dec. 2013. Tyson, Lois. Using Critical Theory: How to Read and Write about Literature. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge, 2011. Print. Walker, Alice. "Everyday Use." American Short Stories Part 3. N.p.: n.p., n.d. 184-91. Print.