Battistoni-Syllabus - The Leading Change Network

advertisement

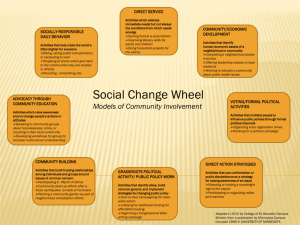

PSP 303: Community Organizing: People, Power, and Change Providence College Instructors: Project Coaches: Class Meeting: Rick’s Office Hours: Kaytee’s Hours: Fall 2012 Rick Battistoni (rickbatt@providence.edu) Office: FAC 402 Kaytee Stewart (kstewar2@providence.edu) Office: FAC 402 Annie Wendel (awendel@friars.providence.edu) Patrick Mahoney (pmahone2@friars.providence.edu) Thursdays 2:30-5:00 pm, FAC 405 Thursday 11:30-2:00; or by appointment Tuesday, 2:00-5:00; or by appointment "In democratic countries, knowledge of how to combine is the mother of all other forms of knowledge; on its progress depends that of all the others." -Alexis De TocquevilleINTRODUCTION A. OBJECTIVES: PSP 303 is a relatively new course at PC, although we have experimented with incorporating the concepts and skills of community organizing into the PSP curriculum. Alumni working in communities or in the for-profit or not-for-profit sectors have told us that this was a missing element in our curriculum, so we worked to refine a course in community organizing that would become a requirement for the PSP major and minor. By requiring this course in the PSP curriculum we emphasize that there are “two legs to social justice”: direct service and organizing or advocacy. As de Tocqueville argues, organizing (“knowledge of how to combine”) is a form of knowledge that is essential to individual and collective success in democratic communities. To fulfill its promise, democracy must meet challenges of equity, inclusion and accountability. This requires an “organized” citizenry with the power to articulate and assert its interests effectively. However, the concerns of many in the United States remain muted due to unequal and declining citizen participation. In this class, students learn how organizers develop leadership to confront these challenges, build community around that leadership, and build power from that community. Students learn how to view social, economic, and political problems from an organizer’s perspective . . . and how to act to solve them. B. COURSE OBJECTIVES, LINK TO PSP CORE COMPETENCIES: This course helps meet at least four of the six “core competencies” of the Public and Community Service Studies major and minor. This course will help you develop the following skills: 1. Eloquent listening. Through experiences and skill-building in storytelling (and listening to the stories of others), finding common interests in one-to-one conversations, and stakeholder analysis and mapping, you will be developing your capacity to “listen eloquently” in your attempts to achieve community change. 2. Organizational competency. In using an organizing framework to work through your own organizing project, you will learn how to map power in organizations and communities, to analyze organizational systems, and will gain experiences in group process and advocacy. 3. Values Identification and Critical Reflection. In choosing an organizing project that come from your passions and values, you will learn how to align personal values with organizational mission. In addition, by moving back and forth between theory and practice, organizing framework and practical application through your project, you will develop deeper skills in critical reflective practice. 4. Writing and Public Speaking. This course meets the Writing I Proficiency under PC’s new core curriculum, and you will be developing your writing in a few different contexts, with ample opportunity for feedback from other students, coaches, and instructors. You will also have several opportunities to tell your story and present your project, most significantly in a ten-minute oral presentation to the class at some point in the semester. 5. Depending on the project you choose, the course may help develop your Issue and Content Capacities, the sixth “core competency” of the major and minor. We encourage you to identify an organizing project that connects to your interest and passion in a specific issue area, perhaps tied to your major or PSP track or concentration. C. OUTLINE: This course has been adapted for PC and the PSP department from a syllabus and framework designed by Marshall Ganz, a longtime organizer and Lecturer at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. PSP 303 focuses on how to build organizations through which people can make their voices heard, and turn their values into action. We ask three questions: why people organize, how organizing works, and how you can become a good organizer. As participant observers responsible for their own organizing project, students will learn how to examine their experience as data for reflective practice. A praxis of organizing helps students learn to map power and interests, develop leadership, build relationships, motivate participation, devise strategy and mobilize resources to create organizations and win campaigns. This approach is equally useful for community, issue, electoral, union, and social movement organizing, and will be useful to you whether you have “real world” organizing experience or not. D. REQUIREMENTS: 1. Project: Students base class work on their experience leading an “organizing project” of their own choosing that requires an average of 4-5 hours per week (example: consider working on your project 2 evenings or one afternoon per week). Students may initiate their own projects or serve with one of a variety of community or campus organizations. They may continue an existing project or start a new one. An “organizing project” (1) is rooted in your values; (2) is intended to achieve a specific outcome by the end of the semester; and (3) requires mobilizing other people to participate in achieving the outcome. Getting Started on the Project One-to-One Meetings: To facilitate project selection and to get further acquainted, Rick and Kaytee will meet one-to-one with students during the first week of class. Once you have solidified your project, you will schedule a meeting with your assigned coach. Student Panel: During or immediately after the first class session (September 6), a panel of PC students will share their experiences organizing projects in the past, and how you can make this class work for you. Action Skills Session: To acquaint you with a range of leadership tools and organizing skills useful in your projects, you are required to participate in a Saturday “Skills Session,” to be conducted September 15, from 9:00 AM to 3:00 PM, in Cambridge, MA. We will be participating in this session alongside students in similar courses from Harvard, Holy Cross, and UMass. More details to follow… Project Report Form: By Monday, October 1, you will fill out and submit the Organizing Project Report Form (available on SAKAI course site), so everyone, including the instructional team, can see your plans and offer feedback and advice. 2. Class: Classes meet for 150 minutes each week for thirteen weeks. Students use an “organizing praxis” drawn from readings to reflect critically on their experience and observations. Sessions alternate between discussion of new material and of student projects. Students are required to attend all sessions, do the reading and take an active part in discussions. Students will also sign up to do a 10-minute oral presentation to their classmates on their project and the organizing topic of the week (more details later). 3. Reading: Readings are assigned for each class meeting. Readings combine theory, practice, and history and you can expect to be reading 60-80 pages a week. Marshall Ganz’s “Organizing Notes” introduce the readings and offer a framework for discussion. 4. Writing: In this course, there will be three forms of required writing. But we also encourage you to keep an organizing journal. This private writing can include descriptive details and free-ranging reflections on your work in the organizing project, classroom discussion, and the readings. This journal can then be the source material for the writing assignments. a. Beginning with the fifth week of classes, students will submit a series of 8 project logs with brief reflections—using a form available on SAKAI—of no more than 2 pages in which they chronicle and then analyze their own experiences in their individual organizing project in light of the topic and readings for that week. At the end of each class these weeks, we will generate questions in class to stimulate reflection. Remember, a total of eight reflections must be turned in to meet the requirements of the course (worth 3 points each). b. At mid-course, on Monday, October 29, students will submit a 5-7-page midterm paper, in which they make an argument as to why their project is or is not working. More details can be found in the midterm paper assignment file in SAKAI. c. At the time a final would have been given for PSP 303, Thursday, December 13, students will submit a 15-20 page final paper analyzing their organizing project. More details can be found in the final paper assignment file in SAKAI. Course evaluation is based not on whether or not a student’s project is a “success”, but on a student’s demonstrated ability to learn from it, to analyze what happened and why. 5. Individual Meetings: Each student should plan on having at least 4 individual meetings with instructional team members. The first meeting will be with Rick and Kaytee, and will take place sometime in the first week (or so) of the course, to elicit students’ ideas about possible organizing projects. After that, you will be scheduling meetings with Pat or Annie aimed at finalizing the selection and timeline of your project and then developing learning objectives and analyzing where your project is at different key points in the semester, as well as to go over outlines of your midterm and final papers. These sessions are intended to be supportive coaching sessions to increase your success in your organizing and in reflecting/writing about organizing. Schedules for meeting times will be circulated. In addition, if students would like or need additional meetings, these may also be arranged. 6. Final Grade Criteria. Final grades are based upon the following: Weekly reflections and project logs: 24% Midterm Paper: 20% Final Paper: 30% Class Participation: (rubric to be determined) 26% E. READING MATERIALS: In addition to Dr. Ganz’s Organizing Notes (Notes in Weekly Program) and the Bergin, Stewart, & Woodland manual “A Guide to Organizing on the Providence College Campus” (Manual), copies of which will be handed out the first day of class, two books are required for this course. They are: 1. Mary Beth Rogers, Cold Anger. University of North Texas Press, 1990. 2. Stephen Smith, Stoking the Fire of Democracy, ACTA Publications, 2009. All other required readings will be available on the course SAKAI website. F. WEEKLY PROGRAM The following is the schedule of class meetings and reading assignments. Special due dates are noted in bold. Letters to the right of each reading indicate whether the focus is theoretical (T), practical (P) or historical (H). Part I: INTRODUCTION TO ORGANIZING 1. Introduction to the Course: September 6 Welcome! Today we discuss our goals for the course, our strategy for achieving them, and course requirements, including the central organizing project out of which your learning will occur. We will have a chance to introduce ourselves through telling our stories, since the experiences and perspectives each student brings to the course will be one of our “texts” for learning. The readings assigned for the first class are meant to orient you to the course. Ganz’s “What is Organizing” and the excerpts from the Organizing Manual summarize our initial organizing praxis. a. Marshall Ganz, “What is Organizing” (emailed to students before class began) (T) b. Bergin/Stewart/Woodland Manual (pp. 2-3, 14-16) (T/P) 2. Telling Your Public Story: September 13 This week we begin to construct our public stories, articulating our values, interests, and our motivations to organize and to learn organizing. Public narrative is the art of translating values into action. It is a discursive process through which individuals, communities, and nations construct their identity, make choices, and inspire action. Because it engages both “head” and “heart”, it can instruct and inspire - teaching us not only how we should act, but moving us to act. Leaders use public narrative to interpret themselves to others, engage others in a sense of shared community, and inspire others to act on challenges that a community must face. It is learning to tell a story of self, a story of us, and a story of now. It is not public speaking, messaging or image making. This is important to understand not only for its own sake, but because whenever you assume leadership, people expect an account of who you are, what you are doing and why you are there. Questions of what I am called to do, what the community is called to do, and what we are called to do now are at least as old as Moses’ conversation with God at the Burning Bush: Why me? asks Moses, when he is called to free his people. And, who – or what - is calling me? And, why this group of people? Why here, why now, why in this place? We will spend most of this class session doing an exercise, based on some homework done over the week, where each of you will get to tell your own life stories/histories (refer to Life Story Exercise). The readings for the week will help us understand what comes out of the exercise. Marshall Ganz talks about the tradition of public narrative, and how story/narrative can be used as a resource in organizing. Barack Obama’s 2004 speech helps us see connections between the personal and our public story. Rogers discusses the motivations, and “fire,” behind Ernesto Cortes’ organizing in Texas. Smith makes connections between telling one’s story and finding the “why” behind what a person does and values. a. b. c. d. Marshall Ganz, “What is Public Narrative?” (Notes, pp. 7-20) Smith, Stoking the Fire…, Chapter 1. (P/T) Rogers, Cold Anger, pp. 183-192. (P/T) Barack Obama, Speech from 2004 Democratic National Convention, 2004. (Notes, pp. 106-108) SKILLS SESSION Saturday, September 15, 2012 9:00 AM to 3:00 PM All students enrolled in PSP 303 are required to take part in this "skills session" to acquaint themselves with basic leadership skills needed to make an organizing project work: relationships, interpretation, and action. 3. The Praxis of Organizing: September 20 This week we turn to our method of learning reflective practice, or how to get the most out of your organizing project. Thich Nhat Hanh reflects on uses and abuses of theory in learning practice. Fiske and Taylor explain where our theories come from and how they both shape our learning, and inhibit it. Smith challenges us to act, and even fail, as the only vehicle to learning. Kierkegaard calls attention to the fact that learning practice takes emotional resources, as well as cognitive and behavioral ones. a. Marshall Ganz, “Learning to Organize” (Notes, pp. 2-6) (T) b. Thich Nhat Hanh, Thundering Silence: Sutra on Knowing the Better Way to Catch a Snake, "The Raft is Not the Shore," (pp.30-33). (P) c. Smith, Stoking the Fire of Democracy, Introduction, Chapter 4. (P/T) d. Susan Fiske and Shelly Taylor, Social Cognition Chapter 6 “Social Schemata” (pp. 139-42; 171-181) (T) e. M.S. Kierkegaard, “When the Knower Has to Apply Knowledge,” from “Thoughts on Crucial Situations in Human Life,” in Parables of Kierkegaard, T.C. Oden, Ed. (P) PART II: WHY PEOPLE ORGANIZE 4. The Organizing Tradition: September 27 What is the organizing tradition? These readings give a sense of its depth and breadth. While its roots are ancient (as seen in your reading from Exodus), popular, civic, and religious traditions that converged in the founding of the US later expressed themselves in the Civil Rights Movement. The tradition has played out differently elsewhere, as we will see later in the course. Branch’s excellent (and absolutely essential) account of the Montgomery bus boycott shows how organizing actually works. a. The Bible, Exodus, Chapter 2-6, (pp.82-89). (H) b. Taylor Branch, Parting the Waters, Chapter 4, “First Trombone” (pp. 120-142) and Chapter 5, "The Montgomery Bus Boycott," (p.143 -205) (H) c. “The Organizing Tradition at Providence College” (Manual (pp. 17-21) (H) Organizing Project Report Form Due Monday, October 1 5. Actors, Goals, Interests, and Resources: People, Power, & Change: October 4 We begin mapping the social world within which each organizing project unfolds. Who are the actors? What do they want? What resources can they use to get what they want? An organizing campaign begins with a constituency: people whose interests are at stake whom you can motivate to commit their resources to asserting those interests. Who are “your” people? What “intolerable condition” do they want to change? What outcome could they hope to achieve by organizing? How could they turn their resources into the power they need to achieve that outcome? Will it require building power “with” each other or challenging power “over” them held by others? How can you organize your time so as to build the needed capacity by the end of the semester? Who are the other potential actors: are they potential allies, opposition, competition? Readings on actors, values, interests, and power can help you discern the motivations of your constituency, as well other parties, including an opposition. We can view power as relational, emergent from interactions among interests and resources. Loomer argues that these interactions can yield “power with” others or the “power over” others. Miller challenges us to look at the connections between gender and power, while Guinier and Torres call attention to the political implications of how we understand our “interests”. Rogers discusses the understanding and use of power by the Industrial Areas Foundation in Texas. Use the “four questions to track down the power” (in Ganz) to map the power relations of the community in which your project is situated. a. Marshall Ganz. “People, Power and Change,” (Notes, pp. 21-39). b. “Identifying Key Players” and “Mapping” in Manual (pp. 6-12, 23-26). c. Bernard M. Loomer, “Two Kinds of Power,” The D.R. Sharpe Lecture on Social Ethics, October 29, 1975, Criterion, Vol. 15, No.1, 1976 (pp. 11-29). (T) d. Jean Baker Miller, “Women and Power,” from Women’s Growth in Connection, 1991 (T) e. Rogers, Cold Anger, pp. 23-31; 45-54. (T/H) f. Guinier & Torres, The Miner’s Canary, “Race as Political Space”, (pp. 67– 82). (T) First Student Presentations Log & Reflection # 1 Due—10/7: Actors, Goals, Interests, & Resources/Power PART III: HOW LEADERSHIP WORKS IN ORGANIZING a. b. c. d. e. f. g. 6. Structuring Leadership: October 11 Organizers mobilize communities by mobilizing leaders within those communities. Where do leaders come from, how do we know one when we see one, how are they recruited, how are they trained, what do they actually do? What is leadership? A position we hold? Or a practice we do? And if it is a practice, what does it consist of? How can we structure it so that it enables a constituency to achieve their goals, not only the personal goals of whoever is in charge? The selection from Exodus addresses the challenge of earning leadership by letting others earn it, and Rogers chronicles the use of Moses’ story by organizer Ernesto Cortes. Freeman and King challenge us to examine our assumptions about leadership so we can lead more effectively. Marshall Ganz. “Leadership” (Notes, pp. 53-60). Jo Freeman, “The Tyranny of Structurelessness,” Berkeley Journal of Sociology (‘70). (P) The Bible, Exodus, Chapter 18 (H) Rogers, Cold Anger, pp. 13-17. (H/P) Dr. M.L. King, Jr. A Testament of Hope, "The Drum Major Instinct," (p.259-67). (H) Additional Recommended readings on Leadership: J. McGregor Burns, Leadership, Chapter 1, “The Power of Leadership,” (pp.18-28) (T) R. Heifetz, Leadership Without Easy Answers, “Values in Leadership”, Chapter 1, (pp.13-27). (T/P) Log & Reflection #2 Due 10/14: Leadership 7. Communities of Interest: Relationship Building: October 18 Organizers build relationships to construct a “community of interest,” a constituency. Through relationships we come to understand our interests and develop the resources to act upon them. Gladwell explains the power of relational networks and exchanges—with people “like us” and people not “like us”—in everyday life. Bobo offers some hints on recruiting. Rogers and Smith give us an understanding of the 1-1 as a recruiting and relationship-building tool. This week we will have the opportunity to discuss our projects in more depth, having spent several weeks actively organizing. This will be an opportunity to share goals, progress, successes to date, and obstacles with the rest of the class. Students and the instructors will be resources for support and problem-solving. a. Marshall Ganz, “Relationships” (Notes, pp. 40-52). b. Manual, “Building Relationships” (p. 4-5) c. Malcolm Gladwell, “Six Degrees of Lois Weisberg,” in The New Yorker, January 11, 1999 (pp. 5263). (T) d. Kim Bobo, et al, Organizing for Social Change, Ch. 10, “Recruiting,” (pp.110-117). (P) e. Rogers, Cold Anger, pp. 55-64 (P) f. Smith, Stoking the Fire…, Chapter 2. (P/T) Log & Reflection #3 Due 10/21: Mobilizing Relationships 8. Turning Resources into Power: Strategizing: October 25 Strategy is how we turn what we have into what we need in order to get what we want. It is both analytic and imaginative work, figuring out how we can use our resources to achieve our goals. We reflect on a “classic” tale of strategy recounted in the Book of Samuel: the story of David and Goliath, a tale that argues (as the Ganz piece shows) insurgents can compensate for lack of resources with resourcefulness if they develop the “strategic capacity”. Alinsky, Bobo, and Smith offer some “how to’s” for organizing strategy and tactics. Effective deliberation can improve the chances of good strategizing and Bobo spells out how to make deliberation work better by holding good meetings. Marshall Ganz. “Strategizing” (Notes, pp. 76-88) “How To” section of Manual (pp. 27-36) The Bible, Book of Samuel, Chapter 17, Verses 4-49. (H) Marshall Ganz, from “Why David Sometimes Wins: Strategic Capacity in Social Movements” in Rethinking Social Movements (pp. 1-10). (T) e. Kim Bobo, Organizing for Social Change, Chapter 12, “Planning and Facilitating Meetings,” (pp.128139). (P) f. Saul Alinsky, Reveille for Radicals, Chapter 4, “The Program” (pp. 53-63). (P) g. Si Kahn, “Strategy,” in Organizing (pp. 155-174). (P) h. Smith, Stoking the Fire, Chapter 3. (P) a. b. c. d. Log & Reflection #4 Due 10/28: Strategy, Resources, & Power Midterm Paper DUE MONDAY OCTOBER 31 9. Mobilizing Resources: Action: November 1 Organizers mobilize and deploy resources to take action based on the commitment they can call forth from others. The way we mobilize resources influences how we can deploy them and vice versa. Some draw most of their resources from a single constituency, while others draw from multiple constituencies. Some deploy resources to offer services; others, to make claims. We learn this week about how we mobilize resources and how we can deploy them. We also learn how different kinds of action can motivate further action. Sitkin argues the value of "intelligent" early failures. Alinsky provides perspectives on how actions are devised. The chapter from Cold Anger focuses on city-wide claims-making. a. Marshall Ganz. “Action” (Notes, pp. 76-88). b. Sim Sitkin, “Learning Through Failure: The Strategy of Small Losses,” Research in Organizational Behavior, Vol.14, 1992, (pp. 231-266). (T) c. Saul Alinsky, Rules for Radicals, Tactics, (p. 126-36, 148-55, 158-61). (P) d. Rogers, Cold Anger, “Leave Them Alone. They’re Mexicans,” (pp.105-126). (H) Log & Reflection #5 Due 11/4: Action! 10. Communities in Action: Organizations: November 8 Organizers conduct campaigns - rhythms of activity targeted on specific outcomes that are based on a foundation, begin with a "kick-off", gather momentum, and culminate in a peak moment of mobilization when the campaign is won or lost. Mobilized communities are structured as organizations. This requires facing the dilemmas of balancing unity and diversity, inclusion and exclusion, responsibility and participation, leadership and accountability. The Rogers chapter places these dilemmas in the context of how the IAF viewed its specific organizational issues. a. Marshall Ganz. “Organization: Communities in Action” (Notes, pp. 89-102). b. Rogers, Cold Anger, pp. 93-101 (H) Log & Reflection #6 due (11/11): Campaigns and Organizations 11. Our Projects in Light of the History of Community Organizing November 15 Community organizing has a rich history, in different parts of the globe. This week we will examine our own organizing projects in light of several case examples from that history. You will work in groups of 4 to present one of the organizing examples. Organizing Case Studies: a. Dennis Dalton, Gandhi, Chapter 4, "Civil Disobedience: The Salt Satyagraha" (pp.91 -138). b. Randy Shaw, “Cesar Chavez and the UFW: Revival of the Consumer Boycott,” in Beyond the Fields: Cesar Chavez, the UFW, and the Struggle for Justice in the 21st Century, pp. 13-50. c. Abigail Halci, “AIDS, Anger, & Activism: ACT UP as a Social Movement Organization” d. Mahila Milan (Women Together in Hindi): From Demolitions to Dialogue (reading TBD). e. “Occupy Providence”—an “oral case study” with organizers from last year’s campaign. Log & Reflection #7 due (11/18): What can we learn from Organizing History? 12. PART V: Learning the Craft: Becoming a Good Organizer: November 29 This week we reflect on organizing as a craft, art, and vocation: why do we do it, what makes us good at it, what about the rest of our lives, how can we continue to grow as we do it? Heifetz discusses the challenge of accepting responsibility for leadership. Bobo and colleagues discuss the resources and perspectives necessary for organizing for the long haul. Langer reflects on how to work “mindfully.” Smith talks about deploying both mind and body in the work. a. Marshall Ganz, “Becoming a Good Organizer” (Notes, pp. 103-105) b. Ronald Heifetz, Leadership Without Easy Answers, Chapter 11, "The Personal Challenge," (pp. 250271). (P) c. Bobo, “Working for the Long Haul,” pp. 338-344. d. Smith, Stoking the Fire…, Chapter 5. (P) Reflection #8 Due (12/2): Becoming a Good Organizer 13. PART VII: Organizing in the Big Picture: December 6 So what does organizing contribute to public life? The readings this week begin with Alinsky's call for broader participation in democratic governance—as timely now as when it was written in 1946. Rogers concludes her book by arguing the need for greater participation today. And Smith connects the need for participation with that of power and politics. a. Rogers, Cold Anger, “Epilogue,” pp. 193-199. (H) b. Smith, Stoking the Fire…, Chapter 6. (P) FINAL PAPER Due by December 13, 3:30 p.m