Two attribution errors

advertisement

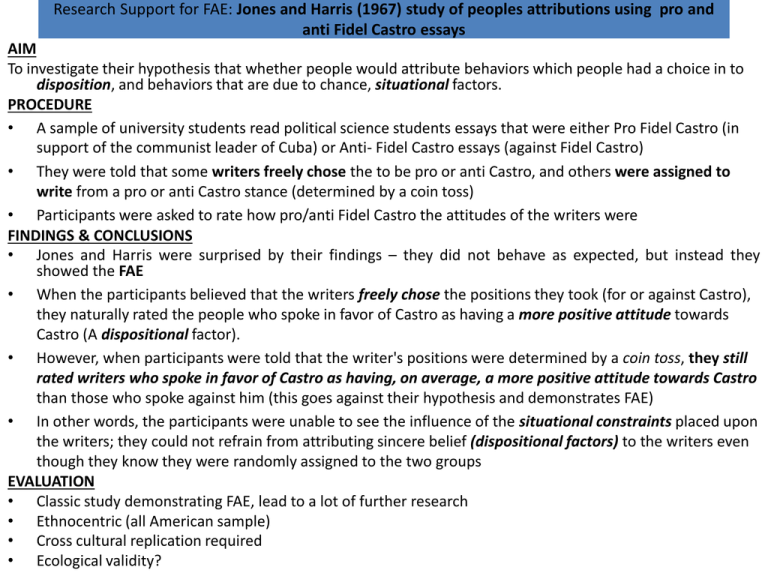

Research Support for FAE: Jones and Harris (1967) study of peoples attributions using pro and anti Fidel Castro essays AIM To investigate their hypothesis that whether people would attribute behaviors which people had a choice in to disposition, and behaviors that are due to chance, situational factors. PROCEDURE • A sample of university students read political science students essays that were either Pro Fidel Castro (in support of the communist leader of Cuba) or Anti- Fidel Castro essays (against Fidel Castro) • They were told that some writers freely chose the to be pro or anti Castro, and others were assigned to write from a pro or anti Castro stance (determined by a coin toss) • Participants were asked to rate how pro/anti Fidel Castro the attitudes of the writers were FINDINGS & CONCLUSIONS • Jones and Harris were surprised by their findings – they did not behave as expected, but instead they showed the FAE • When the participants believed that the writers freely chose the positions they took (for or against Castro), they naturally rated the people who spoke in favor of Castro as having a more positive attitude towards Castro (A dispositional factor). • However, when participants were told that the writer's positions were determined by a coin toss, they still rated writers who spoke in favor of Castro as having, on average, a more positive attitude towards Castro than those who spoke against him (this goes against their hypothesis and demonstrates FAE) • In other words, the participants were unable to see the influence of the situational constraints placed upon the writers; they could not refrain from attributing sincere belief (dispositional factors) to the writers even though they know they were randomly assigned to the two groups EVALUATION • Classic study demonstrating FAE, lead to a lot of further research • Ethnocentric (all American sample) • Cross cultural replication required • Ecological validity? Research Support for FAE: Ross et al. (1977) Quiz Game Study AIM • The aim of this ingenious study was to see if student participants would make the fundamental attribution error (FAE) even when they knew that all the actors were simply playing a role. PROCEDURE • In their study, participants were randomly assigned to one of three roles: 1) a game show host 2) contestants on the game show 3) members of the audience (observers) • The game show hosts were instructed to design their own questions. • The audience (observers) then watched the game show go through the series of questions. • When the game show was over, the observers were asked to rank the intelligence of the people who had taken part. FINDINGS & CONCLUSIONS • They consistently ranked the game show host as the most intelligent, even though they knew that this person was randomly assigned to this position, and— more significantly—he or she had written the questions. • They failed to attribute the role to the person’s situation—that is, being allowed to ask the questions and instead attributed the person’s performance to dispositional factors—in this case, intelligence. • The observers showed the FAE even when they know it was random assignments to the two groups EVALUATION • There are some concerns about the experiment. First, the sample is somewhat problematic. The researchers made use of student participants. University students spend their days listening to professors who are seen as authorities. Therefore, one cannot be sure that this response to authority figures who ask questions and give answers is not a learned response rather than an attribution error. • Second, student samples are not representative of the greater population, and therefore it is questionable whether the findings can be generalized. • However, this study reflects what we see in everyday life. People with social power usually initiate and control conversations; their knowledge concerning a particular topic can give others the impression that they are knowledgeable on a large range of other topics as well. Medical doctors and teachers are often seen as experts on topics that are not within their area of expertise. When they publish something outside of their field, their work is rarely challenged. Discussion & Evaluation: The role of culture and the FAE • Fiske & Taylor (2008) highlight that there are cultural differences that somewhat limit the universality of the FAE It is far stronger in people from individualist cultures. • People from collectivist cultures also explain behavior based on dispositional factors , but do so to a lesser degree. • East Asians to use situational factors more in their judgment. They were socialized by their cultures to have an interdependent self and abide by situational norms. • In contrast, socialization in individualist cultures produces an independent self, where people feel less compelled to consider the larger group. ERROR 2: Self-Serving Bias (SSB) • Another error in attribution is the was proposed by Miller and Ross (1975) called self-serving bias (SSB) • This is seen when people take credit for their successes, attributing them to dispositional factors, and dissociate themselves from their failures, attributing them to situational factors. Research support for SSB: Lau & Russell (1980) study of American football players & coaches attributions AIM To examine the attributions given for American football teams winning and losing games PROCEDURES • Lau and Russell looked at thirty-three major sporting events as reported in eight daily newspapers in the USA in autumn 1977. • A total of 594 explanations for winning and losing were found from coaches, players , and sportswriters in 107 articles. • The study used content analysis methodology. • The explanations for winning or losing were coded as follows : -dispositional or situational attribution for success or failure - Stability of attribution - A temporary/unstable cause (eg: bad luck) or a stable one (e.g. good player) . FINDINGS & CONCLUSIONS found that American football coaches and players tend to credit their wins dispositional and stable factors—for example, being in good shape, the hard work they have put in, the natural talent of the team—and their failures: situational and unstable factors—for example, injuries, weather, fouls committed by the other team. EVALUATION Use of real life data Reliability of reported data might be an issue Why do we tend to employ the SSB? • Greenberg et al. (1982) argue that the reason we do this is to protect our self-esteem. If we can attribute our success to dispositional factors, it boosts our self-esteem and if we can attribute our failures to factors beyond our control we can protect our self-esteem. In other words, the SSB serves as a means of self-protection. • It can also be argued that cognitive factors play a role in SSB. According Miller and Ross (1975), we usually expect to succeed at a task. If we expect to succeed, and we do succeed, we attribute it to our skill and ability. • If we expect to succeed and do not succeed, then we feel that it bad luck or external (situational) factors that brought about this unexpected outcome. This also explains why it is not always one way or the other. • But if we expect not to do well, and in fact we do not do well, then we attribute it to dispositional factors; if we expect to fail, and we are successful instead, we tend to attribute our success to external (situational) factors— and luck. • Key Point: What has been described so far is commonly observed in people in the western world. There is, however, an exception. It has been found that people who are severely depressed tend to make more dispositional attributions thus blaming themselves for feeling miserable. Evaluation & Discussion: The role of culture and the SSB • It also seems that there are cultural differences in SSB. In studies carried out by Kashima and Triandis (1986), significant cultural differences were found between US and Japanese students. • In their experiment, Kashima and Triandis asked participants to remember details of slides of scenes from unfamiliar countries. When asked to explain their performance, the Americans tended to attribute their success to ability while the Japanese tended to explain their failures in terms of their lack of ability. This is called a modesty bias. • Chandler et al. (1990) also observed this bias in Japanese students, and Watkins and Regmi (1990) found the same in Nepalese students. But why should this be the case? • The role of culture is pivotal in understanding the modesty bias. Bond et al. (1982) found that Chinese students who exhibited the modesty bias instead of the SSB were more popular with their peers. • Kashima and Triandis argue that it is because of the more collective nature of many Asian societies: if people derive their self-esteem not from individual accomplishment but from group identity, they are less likely to use the SSB.

![Errors in attribution [fae][ssb]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006919180_1-bb27134b2bf049c0a7587c75b05c9ab2-300x300.png)