Anne Cudd, “Capitalism for and Against: A Feminist Debate,” Google

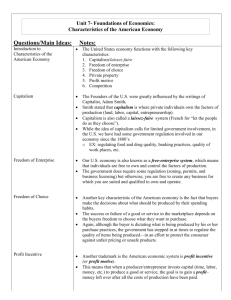

advertisement