Chapter 19 Overview

advertisement

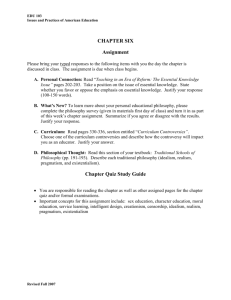

CHAPTER 19 Intellectual and Cultural Trends in the Late Nineteenth Century CHAPTER OVERVIEW Colleges and Universities. The number of colleges increased as state universities and coeducational land-grant colleges sprang up across the nation. Still, less than 2 percent of the college age population attended college. Harvard led the way in reforming the curriculum and professionalizing college teaching. Established in 1876 and modeled on German universities, Johns Hopkins University pioneered the modern research university and professional graduate education in America. Beginning with Vassar College, the second half of the nineteenth century witnessed the establishment of numerous women’s colleges. Alumni influence on campus grew, fraternities spread, and organized sports became a part of the college scene; colleges and universities mirrored the complexities of modern American society. Industrialization altered the way Americans thought and the institutions of higher education. Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution influenced American philosophers, historians, and lawyers. Revolution in the Social Sciences. Social scientists applied the theory of evolution to every aspect of human relations. They also attempted to use scientific methodology in their quest for objective truths in subjective fields. Controversies over trusts, slum conditions, and other problems drew scholars into practical affairs. Classical economics faced a challenge from the institutionalist school. Similar forces were at work in the disciplines of sociology and political science. Progressive Education. Educators began to realize that traditional education did not prepare their students for life in industrial America. Settlement house workers found that slum children needed training in handicrafts, citizenship, and personal hygiene as much as in reading and writing. New theorists argued that good teaching called for professional training, psychological insights, enthusiasm, and imagination, not rote memorization and corporal punishment. John Dewey of the University of Chicago emerged as the leading proponent of progressive education. Dewey held that the school should serve as “an embryonic community,” a mirror of the larger society. He contended that education should center on the child and that new information should relate to the child’s existing knowledge. Dewey saw schools as instruments of reform. Toward that end, he argued that education should teach values and citizenship. Law and History. Social evolutionists affected even the law. In 1881, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., in The Common Law, best summarized this new view, averring that “the felt necessities of time” and not mere precedent should determine the rules by which people were governed. Holmes’s views did not initiate a sudden reversal of judicial practice; indeed, his most notable opinions tended to be dissents. His ideas, however, reflected late nineteenth-century thought, and they gained in influence throughout the twentieth century. Also responding to new intellectual trends, historians traced documentary evidence to discover the evolutionary development of their contemporary political institutions. One product of this new approach was the theory of the Teutonic origins of democracy, which has since been thoroughly discredited. The same general approach, however, also produced Frederick Jackson Turner’s “Frontier Thesis.” If the claims of the new historians to objectivity were absurdly overstated, their emphasis upon objectivity, exactitude, and scholarly standards benefited the profession. Realism in Literature. The majority of America’s pre-Gilded Age literature was romantic in mood. However, industrialism, theories of evolution, the new pragmatism in the sciences, and the complexities of modern life produced a change in American literature. Novelists began to examine social problems such as slums, political corruption, and the struggle between labor and capital. Mark Twain. While no man pursued modern materialism with more vigor than Samuel L. Clemens, perhaps no man could illustrate the foibles and follies of America’s Gilded Age with greater exactitude than his alter ego, Mark Twain. His keen wit, his purely American sense of humor, and his eye for detail allowed Twain to portray the best and the worst of his age. His works provide a brilliant and biting insight into the society of his day. William Dean Howells. Initially for Howells, realism meant a realistic portrayal of individual personalities and the genteel, middle-class world that he knew best. He became, however, more and more interested in the darker side of industrialism. He combined his concerns for literary realism and social justice in novels such as The Rise of Silas Lapham and A Hazard of New Fortunes. Following his passionate defense of the Haymarket radicals in 1886, he moved rapidly toward the left. The most influential critic of his time, Howells was instrumental in introducing such authors as Tolstoy, Dostoyevski, Ibsen, and Zola to American readers. He also sponsored young American novelists such as Hamlin Garland, Stephen Crane, and Frank Norris. Some of these young authors went beyond realism to naturalism, a philosophy that regarded humans as animals whose fate was determined by the environment. Henry James. A cosmopolitan born to wealth, Henry James lived most of his adult life as an expatriate. James never gained the recognition of his countrymen during his lifetime. His major themes concerned the clash between American and European cultures and the corrupt relationships found in high society. Realism in Art. Realism had a profound impact on American painting as well as writing. Foremost among realist artists was Thomas Eakins, who was greatly influenced by the seventeenth-century European realists. As an early innovator in motion pictures, Eakins used the medium to study people and animals in motion. Winslow Homer, a watercolorist from Boston, used all of the realist’s techniques for accuracy and detail to enhance his sometimes romantic land and seascapes. If the careers of Eakins and Homer demonstrated that America was not uncongenial to first-rate artists, two of the leading artists of the era, James McNeill Whistler and Mary Cassatt, were expatriates. During this period, vast collections of American and foreign artworks came to rest in the mansions and museums of the United States. The Pragmatic Approach. It would indeed have been surprising if the intellectual ferment of this period had not affected traditional religious and philosophical values. Evolution posed an immediate challenge to traditional religious doctrine but did not seriously undermine most Americans’ faith. If Darwin was correct, the biblical account of creation was false. However, many were able to reconcile evolutionary theory and religion. Darwinism had a less dramatic but more significant impact upon philosophical values. The logic of evolution made it difficult to justify fixed systems and eternal verities. Charles S. Pierce, the father of pragmatism, argued that concepts could be fairly understood only in terms of their practical effects. William James, the brother of the novelist and perhaps the most influential thinker of his time, presented pragmatism in more understandable language. He also contributed to the establishment of psychology as a scientific discipline. Although pragmatism inspired reform, it had its darker side. While relativism gave cause for optimism, it also denied the comfort of certainty and eternal values. Pragmatism also seemed to suggest that the end justified the means. The Knowledge Revolution. The new industrial society placed new demands on education and gave rise to new ways of thinking about education. Darwin’s theory of evolution influenced almost every field of knowledge. America emerged from the intellectual shadow of Europe, as Americans began to make significant contributions to the sciences as well as the relatively new social sciences, and American literature flourished. Americans of all ages began to hunger for information. Chautauqua-type movements, the growth of public libraries, and the boom in the number, size, and sophistication of newspapers began to satisfy the public’s newfound curiosity. A growing and better-educated population created a demand for printed matter. At the same time, technology reduced the cost of producing newspapers. Papers such as Pulitzer’s New York World and Hearst’s New York Journal appealed to a mass audience and competed fiercely for readers. By the turn of the century, more than five thousand magazines were in publication. Before the 1880s, a few staid publications, such as Harper’s and The Atlantic Monthly, dominated the field of serious magazines. In the 1860s and 1870s, Frank Leslie’s magazines appealed to a broader audience. After the mid-1880s, several new, serious magazines adopted a hard-hitting, controversial, and investigative style and inquired into the social issues of their day. Popular magazines rarely discussed the great issues that preoccupied intellectuals of the day, but some topics traversed both intellectual trends and popular culture. Key Terms and People Pragmatism Realism Naturalism Frontier thesis (Frederick Jackson Turner) Joseph Pulitzer William James William Randolph Hearst Charles W. Elliot Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. Mark Twain Johns Hopkins University Richard T. Ely Charlotte Perkins Gilman William Dean Howells Chautauqua Movement