Culture - UOI - Πανεπιστήμιο Ιωαννίνων

advertisement

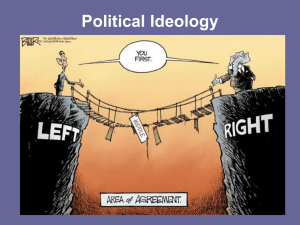

ΠΑΝΕΠΙΣΤΗΜΙΟ ΙΩΑΝΝΙΝΩΝ ΑΝΟΙΚΤΑ ΑΚΑΔΗΜΑΪΚΑ ΜΑΘΗΜΑΤΑ Εισαγωγή στην Ανθρωπολογία της Τέχνης Πολιτισμικές σπουδές (Cultural Studies) και ανθρωπιστικές επιστήμες (CULTURE,CULTURAL STUDIES, RACE, ETHNICITY) Διδάσκων: Καθηγητής Χρήστος Α. Δερμεντζόπουλος Άδειες Χρήσης Το παρόν εκπαιδευτικό υλικό υπόκειται σε άδειες χρήσης Creative Commons. Για εκπαιδευτικό υλικό, όπως εικόνες, που υπόκειται σε άλλου τύπου άδειας χρήσης, η άδεια χρήσης αναφέρεται ρητώς. Culture (high, low, popular, and mass), Cultural Studies, race and ethnicity September 25-27, 2006 3 This week’s lens: Cultural Studies Academic movement started in UK in 1960s. Spread quickly: Europe, US, Australia. Combines aspects of Media studies. - Political science. Comm’n studies. - Sociology. Linguistics. - Gender studies. Anthropology. - Literary criticism. 4 Key concerns of Cultural Studies Relations of culture and power Particularly, power inequalities related to race, class, gender, colonialism. Role of symbols (language, visual images) in creating meaning Particularly as related to power issues. 5 Key concerns of CS (ctd.) Representation: how forms of communication (spoken and written language; music, TV, print media, etc.) present, represent, shape, and distort cultural meaning. Political economy of media—and relationship to messages and meanings: How ownership of cultural production 6 affects products and interpretations. Key concerns of CS (ctd.) Texts and audiences What possible meanings do we draw out of (media) texts? How do (media) audiences interpret texts differently—and why? Cultural (and personal) identity How do we identify ourselves and others? How do cultural/media “products” contribute to identification? 7 Definitions of “culture” Classical (British 19th and 20th century) literary definitions. Anthropological tradition’s definition. Newer, CS-oriented definitions Rejected literary. Built on and expanded anthropological. 8 Culture in the classical literary tradition “Culture” was linked to “cultivation” Agriculture. Growing (crops). The “cultivated” mind (properly “trained) and the “cultured” person. 9 Matthew Arnold’s influence 19th-century UK poet and cultural critic. Arnold’s definition of “culture” The best that has been thought and said in the world. Belief that reading, thinking, and observing (human “cultivation”) would bring about moral perfection A “better,” more civilized, social world. 10 Matthew Arnold (1822-1888), English poet and cultural critic 11 Implications of Arnold’s view The world can be divided into the “cultured” and the “uncultured” Or the civilized and the uncivilized. “Culture” and “civilization”—the domains of the educated (and wealthy)—are superior to the “anarchy” of the “raw and uncultivated masses”. Thus, “culture” is class-dependent And only available to the upper classes. 12 Expanding Arnold: Leavisism 1930s: literary critics Frank Raymond Leavis (1895-1978) and Queenie Roth Leavis (19061981). Among their famous writings: “Mass Civilization and Minority Culture” Culture is “high point” of civilization. Culture is the concern of the educated minority. 13 Leavisism’s claims Elite classes have certain obligations Define—and defend—the “best” of culture (literary, musical, artistic). Criticize—and, arguably, eliminate—the worst of mass culture Advertising, movies, popular fiction. 14 Culture in the anthropological tradition An entire—and distinctive—way of life. In other words: lived experience. 15 Enter Cultural Studies (1960s) Direct reaction against views of Arnold and Leavises; adaptation of anthropological. Raymond Williams (1921-1988), CS pioneer: anti-elitist. Re-visioned culture as “a whole way of life”. Concerned especially with working class’s experience And how working class people actively 16 construct their own cultures. Culture as redefined by CS As a “whole way of life,” It includes everyday practices AND learning, arts, and other expressive aspects How we dress, our holidays, our daily rituals. Our everyday meanings and values. Our norms. How we express ourselves. In short, “culture is ordinary” (Williams). 17 Result of CS’s re-definition Studying or talking about a group’s “culture” could include. Everyday practices. Arts, media, entertainment modes previously dismissed as “low” or “mass” were studied with respect and even sympathy Newspapers, television, boxing matches, soap operas, NASCAR, romance novels, prom dresses. 18 In other words… Everyday culture—including the culture of non-elite classes within our own societies—was given legitimacy. Scholars (and cultural critics) began to value the shared traditions of “ordinary” people Not only the elite classes. 19 Williams’s paradoxical claims A of group’s (re-defined) culture is its complex Meanings generated by ordinary individuals. Lived experiences of its members. Texts and practices engaged in by people as they lead their lives… 20 …BUT… “Culture does not float free of the material conditions of life… “Meanings and practices are enacted on terrain not of our own making even as we struggle to creatively shape our lives” What did Williams mean by this? 21 To address this paradox… We must detour into other key CS concepts Then we’ll circle back to issues of high vs. low culture. mass, folk, and popular culture. 22 Other key CS concepts relevant to ICC (including mass comm) Ideology. Hegemony. Race, racialization, and racisms. Ethnicity. The nation-state. The imagined community. Hybridity. Identity. Subject position. And how all of these relate to POWER. 23 Ideology exercise Divide into groups. Each group discusses (lists) ONE question How does one class justify dominating another? How does one race justify dominating another? How does one sex justify dominating another? How does one nation justify dominating another? Provide examples from popular culture. 24 Ideology What does this word mean to you? What is an ideology? The term ideology was coined (by a 19thcentury French philosopher) to mean “the science of ideas”. Since then, has taken on many other meanings. Here are some of the most common. 25 #1. Value-neutral conception Systematic body of ideas—a worldview— articulated by a particular group of people “Pattern of ideas, belief systems, or interpretive schemes found in a society or among a specific social group” (Hall). 26 What this implies an individual doesn’t have an ideology. but an individual may reflect the ideology of the group she’s a member of. 27 #2. Karl Marx’s definition “False consciousness”: a masking, distortion, or concealment The way some cultural texts and practices present distorted images of reality. Ideology works in interest of the powerful and AGAINST interests of the powerless. 28 Karl Marx (1818-1883) 29 Results of ideological distortion, in Marx’s view Conceals reality of domination from those in power: dominant class do not see themselves as exploiters. Conceals reality of domination from the powerless: they don’t see themselves as exploited. 30 #3: focus on “ideological forms” Texts (mediated) always present a particular picture of the world, always take sides, thus reflect producer’s ideology. All texts are ultimately political: they offer one view or another (but not a multiplicity of views!) of how the world is. Differing ideological significations of reality compete with one another. 31 #4: ideology as “material practice” French Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser (1918-1990) said Ideology isn’t simply a body of ideas, but rather “material practice”. Ideology is encountered in practices of everyday life. 32 Louis Althusser (1918-1990) 33 Examples of “material practice” that reflects ideology Rituals and customs that bind us to the social order, a social order marked by enormous inequalities of wealth, status, and power Examples: taking summer vacations, giving gifts at Christmas. 34 Yes, Althusser would say… These things give us pleasure, release tensions. But ultimately they return us to our places in the social order Because they reproduce the social conditions necessary for capitalism to continue. 35 What produces and maintains (dominant) ideology in society? Althusser talked about “ideological state apparatuses” (ISAs) Family. Education system. Church. Mass media. These ISAs “train” us to follow and perpetuate the values and rules of the dominant classes. 36 ISAs vs. RSA Althusser: because of the power (and willingness) of the ISAs to do the work of the powerful… The Repressive State Apparatus (government, military, courts) don’t have to resort to force The ISAs do their jobs. And make us into good, law-abiding students, family members, citizens, church members, capitalists. Who don’t complain, don’t try to overthrow the government, don’t try to overthrow the corporation heads (and our bosses). 37 As a result… Ideology (worldview maintained and “taught” to us by the ISAs) comes to be seen as natural (as opposed to constructed). universal (as opposed to particular). complete (as opposed to incomplete). neutral (as opposed to partial/biased). legitimate (as opposed to illegitimate). “common sense” (as opposed to a particular, chosen, preferred sense). 38 #5: ideology as myth French social philosopher Roland Barthes. Called ideologies the “myths” of our culture/society. In this sense, myth isn’t (necessarily) fictional But it’s a story we tell ourselves about ourselves. What are some American myths (in Barthes’s sense)? 39 Roland Barthes (19151980) 40 In all of these definitions (except #1), ideology is Meaning in the service of power not just a value-neutral set or system of ideas. Rather, a system that underlies, supports, and justifies a group’s Exercise of power. Maintenance of power. Struggles for power. 41 Is this clear? Maybe Antonio Gramsci can help. 42 Antonio Gramsci (1930s): “Hegemony” Kind of power that arises from ideological tendencies of mass media to support established power system and exclude opposition and competing values. Not imposed via coercion. But constantly sought after, struggled over, negotiated, and re-negotiated. 43 Antonio Gramsci (18911937) 44 Key insight of Gramsci’s hegemony theory The ruling classes in capitalist society (unlike Hitler’s Germany or Stalin’s USSR) don’t HAVE to resort to physical force, violence, or martial law Direct coercion is unnecessary! And, in fact, is LESS effective in the long term for maintaining social power. 45 Hegemony (ctd.) In hegemonic systems, dominance of ruling group is STRENGTHENED because people (non-dominant) consent to their own submission! We come to accept existing (and unequal) power relationships as normal, natural, “common sense,” the only way. 46 How? The ruling class doesn’t directly force us to accept its will. Rather, the dominant present themselves (often through the media) as the group best equipped to meet our needs and we come to agree (for a while…) e.g., we accept that corporations, government act in our best interests. 47 Meaning that… the “masses” (common people) consent to their own domination, seeing it as completely normal (or failing to question it)! the dominated will find their own reasons— which DO actually make sense!—to go along with their domination. For example… 48 Hegemony in our daily lives Grades. Christmas presents. Body image. Work. 49 So what happens in hegemonic systems? Dominant classes exercise social and cultural leadership. We consent to, and perpetuate, a system that disadvantages us. In finding our own good reasons to go along with the system… We fail to challenge or question the system. Let alone call for its overthrow! 50 However… Hegemonic domination is a constant struggle. Consent must be continually won and re-won. Concessions are made so that the dominated will not overthrow the entire system But instead will be given new reasons to accept it. New things to consent to. The media are often the sites of this struggle. 51 Hegemony is maintained Because dominant have advantages Easier access to media. More input into media representations of “reality”. And media themselves are huge corporate powers. 52 Given all this CS on culture. CS on ideology and power. We might not be surprised by CS’s explanations of Race. Ethnicity. Nation. Identity. 53 CS on race, racialization, and racisms Stuart Hall: races don’t exist apart from representation. What does this mean? 54 To paraphrase Race is a social (and communication) construct rather than a biological fact. Race is “constructed” by looking at observable characteristics And then working backwards to “create” a race. 55 The fluidity of race New Mexico. The Irish in New York (mid 1800s). The Jews in US (late 1800s). “black blood”. 56 CS on race and power CS argument: race is a construct (multifaceted concept) developed in order to justify power differentials Labor market. Economy. Housing market. Education system. Media. Legal system. Immigration. 57 Race and nationhood If you’re a member of a minority race in a nation Are you “truly” a member of the nation? Blacks in US. Blacks in UK. Blacks in South Africa during apartheid. 58 CS on ethnicity A cultural concept An ethnic group’s members share Norms. Values. Beliefs. Cultural symbols and practices. all of which developed under specific historical, social, political contexts. 59 What ethnicity does Encourages sense of belonging Based (at least in part) on common mythological ancestry (why “mythological”?) Shared (or believed to be shared) history, language, culture. 60 Ethnicity as “relational concept” I’m a member of ethnic group X because I’m not a member of Y or Z. We define our ethnicity by contrasting ourselves to “out groups”. Implies power relations Some groups are at the “center,” while others are at “periphery”. Examples in US? 61 CS on the nation-state The nation-state is an invention Not a “natural” (naturally occurring) group. Rather, a contingent historical-cultural formation. Prime example? The US! 62 Nation-states and national identity Nation-state: a political concept An administrative apparatus. Group of people with shared government, laws, leaders who have sovereignty over defined body of land. National identity: “imaginative identification” with the symbols and discourses of the nation-state. 63 Careful! National cultural identities are not coterminous with state borders. Consider Jewish, African, Indian, cultural identities. 64 Nation as “imagined community” Benedict Anderson (1983) argued that nations are “imagined communities”. What might this mean? Not “false”. But simply, an idea—something that exists in our heads if not in physical space. We don’t know most of our fellow Americans. But we have shared ideas—and we believe ourselves to be a unity. 65 Hybridity Basically, cultural mixing. Few cultures are homogeneous Our culture reflects hybridity. Few individuals have ancestors from only one culture We are hybrids as individuals. As a result of mixing, we create new identities “African-American,” “Italian-American,” “Afro-Caribbean,” “Pakistani-British”. 66 Multiple identities No one of us has an identity that is “pure” or “fixed” We are each a hybrid. At any moment, we each can be described as belonging to one or more Ethnicity. Nation. Sex. Race. Occupation. Class. 67 Hence, multiple “subject positions” How are you, or can you be, addressed? What roles do you play? Mother, sister, daughter. Boss, employee. Student, teacher. Friend, co-worker. Fellow church member, club member, team member. 68 Recap: key CS concepts Ideology. Hegemony. Race, racialization, and racisms. Ethnicity. The nation-state. The imagined community. Hybridity. Identity. Subject position. 69 Link to our course? Popular culture—particularly as transmitted via the mass media—is arguably the most important “site” in our lives in which these issues are played out, spelled out, and contested. So let’s get back to “culture” High, low, popular, and other. 70 Recap: “high” culture, etc. Arnold and the Leavises (19th-20th C. UK) define culture as the “best”. View that culture is the domain only of the minority Educated, moneyed elite. What has come to be called “high culture”. By contrast, what the non-educated, nonmoneyed everyday folk do is uncivilized, uncultured: “low culture”. 71 CS: mid-1960s and beyond New approach to culture. Culture as ordinary, everyday. Entire ways of life Regardless of class/status. 72 Moreover, CS argues There is no legitimate grounds for drawing distinction between “high” and “low” culture. Artistic forms, whether Shakespeare or WWF broadcasts all expressive and creative. all are socially created. Who is to decide which is more worthy? 73 While many people still do distinguish “high” vs. “low” . . . High: cultural activities of the wealthy or elite: opera, ballet, symphony, great literature, fine art. Low: all other In other words, activities of the non-elite: music videos, TV game shows, professional wrestling, NASCAR, graffiti art, Jackie Chan movies. 74 CS (and many other scholars) prefer to speak of… “popular culture”. rather than demeaning non-elite culture as “low”. 75 How might we define “popular culture”? Systems or artifacts that most people share and that most people know about. Made popular by and for the people. Speaks to—and resonates from—the people. But NOT usually created BY the people! Why not? 76 Popular culture as “mass culture” Most popular culture forms—movies, TV shows, magazines, videos, CDs—are produced by large corporations And are then sold to “the people”. Hence, the music, art, film, television (etc.) businesses were called “the culture industries” by Adorno and Horkheimer (1940s cultural critics). 77 The “culture industries” Acknowledgment of mass-produced nature of popular culture “products” CDs, DVDs, magazines, paperback novels, etc. Acknowledgment of for-profit nature of the companies that make and market them Sony, Disney, Time-Warner, etc., aren’t in it for love! 78 Production vs. consumption: where’s your focus? Frankfurt School (“Critical Theory”) of 1940s leveled criticism on the production end of the chain (critique of “mass culture”). CS focuses on the consumption end (thus prefers the term “popular culture”), inquires into How do we (consumers, ordinary people) use the products of the culture industries? How do we interpret them? What meanings/values do we give them? Why are these things important to us? 79 Depending on your focus If you’re focused on the production end (the corporate, mass-produced, for-profit aspects), you’re probably more likely to speak of “mass culture”. If you’re focused on the consumption/ interpretation end, you’re probably more likely to speak of “popular culture”. 80 Why popular culture is so important to ICC (Martin/Nakayama) Popular culture plays an enormous role in explaining relations around the globe. It is through popular culture that we try to understand the dynamics of other cultures and other nations. For many of us, the world exists through popular culture. 81 Why popular culture is so important more generally It’s everywhere Disseminated widely (in many cases, globally). It’s impossible to avoid. We all have easy access to it. It comes at us from all directions. It comes at us every moment of our lives. We wear it, buy it, think about it, listen to it, read it, watch it. 82 And on the positive side… Popular culture serves important social functions Windows onto the world. Shared experiences and (parasocial) relationships. Forum for public discussion (especially, but not only, the news). Shaper of opinions. Shaper of identities. Shaper of meanings. 83 But popular culture does not work monolithically! What do I mean by this? Hint: recall Hall’s encoding/decoding model of communication. 84 “encoding/decoding” programme as ‘meaningful discourse’ encoding decoding frameworks of knowledge frameworks of knowledge relations of production relations of production technical infrastructure. technical infrastructure. 85 Claims Hall makes Producers of cultural texts (TV shows, ads, movies, books, videos) operate within specific cultural contexts And produce out of their own “frameworks of knowledge”. But we consumers consume the texts within our own contexts. We don’t find the same meanings as the producers Or each other! 86 However, Hall claimed… We don’t necessarily have 6 billion “reading positions” Hall identified 3 reading positions, depending upon a reader’s class (and identification with producer): Dominant. Negotiated. Oppositional. 87 Popular culture, then… Is a “site” of struggle. We have competing, even conflicting, interpretations of what a cultural text means And what values it represents. And whether we like (approve of) it or not. And if it’s offensive or agreeable. We offer different decodings and struggle over them. We “negotiate” the meanings of cultural texts. 88 How might we interpret U. of North Dakota Fighting Sioux. Florida State U. Seminoles. Washington Redskins.. Atlanta Braves. Cleveland Indians Insult/racial slur? Compliment/honor? 89 Popular culture and problems of representation The big question: Do popular culture texts (especially those depicting cultures other than our own) truly, fairly, accurately represent the cultures they claim to be showing? 90 For example… Is Jackass a representation of America, quintessential Americans and quintessential American values? or only a selective portrait of a small group of Americans? How might Jackass (if viewed outside the US) create or reinforce stereotypes about Americans? 91 How CS approaches “criticism” of popular culture The important questions Not whether a cultural text is “good” or “bad” (in terms of quality) Rather, What ideologies are conveyed, overtly or subtly? How are individuals and cultures represented? How might representations maintain power differentials? 92 Τέλος Ενότητας Χρηματοδότηση Το παρόν εκπαιδευτικό υλικό έχει αναπτυχθεί στα πλαίσια του εκπαιδευτικού έργου του διδάσκοντα. Το έργο «Ανοικτά Ακαδημαϊκά Μαθήματα στο Πανεπιστήμιο Ιωαννίνων» έχει χρηματοδοτήσει μόνο τη αναδιαμόρφωση του εκπαιδευτικού υλικού. Το έργο υλοποιείται στο πλαίσιο του Επιχειρησιακού Προγράμματος «Εκπαίδευση και Δια Βίου Μάθηση» και συγχρηματοδοτείται από την Ευρωπαϊκή Ένωση (Ευρωπαϊκό Κοινωνικό Ταμείο) και από εθνικούς πόρους. Σημειώματα Σημείωμα Ιστορικού Εκδόσεων Έργου Το παρόν έργο αποτελεί την έκδοση 1.0. Έχουν προηγηθεί οι κάτωθι εκδόσεις: Έκδοση 1.0 διαθέσιμη εδώ. http://ecourse.uoi.gr/course/view.php?id=1201. Σημείωμα Αναφοράς Copyright Πανεπιστήμιο Ιωαννίνων, Διδάσκων: Καθηγητής Χρήστος Α. Δερμεντζόπουλος. «Εισαγωγή στην Ανθρωπολογία της Τέχνης. Πολιτισμικές σπουδές (Cultural Studies) και ανθρωπιστικές επιστήμες, CULTURE,CULTURAL STUDIES, RACE, ETHNICITY». Έκδοση: 1.0. Ιωάννινα 2014. Διαθέσιμο από τη δικτυακή διεύθυνση: http://ecourse.uoi.gr/course/view.php?id=1201. Σημείωμα Αδειοδότησης Το παρόν υλικό διατίθεται με τους όρους της άδειας χρήσης Creative Commons Αναφορά Δημιουργού - Παρόμοια Διανομή, Διεθνής Έκδοση 4.0 [1] ή μεταγενέστερη. • [1] https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/.