Lecture Chapter 04

advertisement

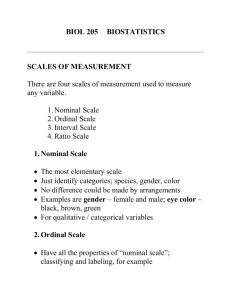

Chapter 4 Conceptualization and Measurement Introduction IF IT EXISTS ---- IT CAN BE MEASURED Measurement is used to gain mathematical insight into our data. When we measure we can compare our data to a standard used for evaluation Through measurement we can inspect, analyze and interpret our information Measurement is essential to Quantitative research Conceptualization. The process of specifying what we mean by a term. A concept is a mental image that summarizes a set of similar observations,feelings or ideas. Some concepts are more abstract than others Introduction, cont. Concepts like “social health,” “prejudice,” and even “binge drinking” require an explicit definition before they are used in research because we cannot be certain that all readers will share a particular definition or that the current meaning of the concept is the same as it was when previous research was published. It is especially important to define clearly concepts that are abstract or unfamiliar. When we refer to concepts like “social control,” “anomie,” or “social health,” we cannot count on others knowing exactly what we mean. Conceptualization in Practice If we are to do an adequate job of conceptualizing, we must do more than just think up some definition, any definition, for our concepts (Goertz 2006). We have to turn to social theory and prior research to review appropriate definitions. We should understand how the definition we choose fits within the theoretical framework guiding the research and what assumptions underlie this framework. Conceptualization in Practice, cont. Example: Do you have a clear image in mind when you hear the term youth gangs? “Neither gang researchers nor law enforcement agencies can agree on a common definition . . . and a concerted national effort . . .failed to reach a consensus” (Howell 2003:75). If you use the term you must have a clear definition of how you are using it. Conceptualization in Practice, cont. Decisions about how to define a concept reflect the theoretical framework that guides the researchers. For example, the concept “poverty” has always been somewhat controversial, because different conceptualizations of poverty lead to different estimates of its prevalence and different social policies for responding to it. Conceptualization is specifying the dimensions of and defining the meaning of the concept Variables A variable is any observation that can take different values Gender, Age, Religion, Ethnicity are variables Variables have attributes or values Attributes (Values) of Gender are: 1. Male 2. Female The main concept in a question on a questionnaire is the variable being measured. Did you vote in the last election. The main concept is Vote. An indicator is the response to a single question Variable Vote (Did you vote?) Indicator = your answer - Yes The values or attributes of the variable vote are: 1. Yes, voted or 2. No, didn’t vote. From Concepts to Observations, cont. Operationalization is the process of connecting concepts to observations. It is the process of choosing the variable to represent the concept. You can think of it as the empirical counterpart of the process of conceptualization. When we conceptualize, we specify what we mean by a term. Example: “Race” is an important concept in social research, but we know it is a social construct and not based on any biological reality. What people mean by “race” has varied over time and from place to place. The term Race is often confused with Ethnicity. From Concrete to Abstract Concepts Concepts vary in their level of abstraction, and this, in turn, affects how readily we can specify the indicators pertaining to the concept. Would you now consider “race” to be an abstract or a concrete concept? A very abstract concept like social status may have a clear role in social theory but a variety of meanings in different social settings. We often use abstract concepts in our theories: crime, abuse, deterrence, substance abuse From Concrete to Abstract Concepts, cont. Usually, the term variable is used to refer to some specific aspect of a concept that varies, and for which we then have to select even more concrete indicators. The important thing to keep in mind is that we need to define clearly the concepts we use and then develop specific procedures for measuring variation in the variables related to these concepts. Measurement Operations The deductive researcher proceeds from defining concepts in the abstract (conceptualizing) to identifying variables to measure, and finally to developing specific measurement procedures. We use variables which are derived from concepts in our hypotheses and research questions? PROCESS Theory – Punishment deters crime We can define the concept crime with the variable ‘physical spousal abuse’ We can define the concept punishment with the variable ‘arrest’ Will arresting physical abusers of spouses deter repetition of the offense? (Research Question) If spousal abusers are arrested on 1st offense then recidivism (repeating offense) will be reduced (Hypothesis) Some concepts are more concrete than abstract i.e. Age – time elapsed since birth But we may have a different meaning in mind – How old in hours, month, years How we will use the variable is important in defining it Sometimes we may have to use qualitative means to define a concept. Instead of using a scientific meaning of ‘diversity’ we may want to use the general public’s meaning of diversity for our research or we may want to know the difference in the meaning of rape for women versus men Available versus Empirical Data Where does our data come from? PRIMARY OR EMPIRICAL DATA – Collected by the researcher (not from library research) AVAILABLE OR SECONDARY DATA Government reports are rich and readily accessible sources of social science data. Organizations ranging from nonprofit service groups to private businesses also compile a wealth of figures that may be available to some social scientists for some purposes. In addition, the data collected in many social science surveys are archived and made available for researchers who were not involved in the original survey project. Using Available Data, cont. Before we assume that available data will be useful, we must consider how appropriate they are for our concepts of interest. We may conclude that some other measure would provide a better fit with a concept or that a particular concept simply cannot adequately be operationalized with the available data. We also cannot assume that available data are accurate, even when they appear to measure the concept in which we are interested in a way that is consistent across communities. Using Available Data, cont. Government statistics that are generated through a central agency like the U.S. Bureau of the Census are often of high quality, but caution is warranted when using official data collected by local levels of government. Constructing Questions Asking people questions is the most common and probably the most versatile operation for measuring social variables. i.e. survey research (Quantitative) Most concepts about individuals can be defined in such a way that measurement with one or more questions becomes an option. Of course, in spite of the fact that questions are, in principle, a straightforward and efficient means to measure individual characteristics, facts about events, level of knowledge, and opinions of any sort, can easily result in misleading or inappropriate answers. Constructing Questions, cont. Memories and perceptions of the events about which we might like to ask can be limited, and some respondents may intentionally give misleading answers. For these reasons, all questions proposed for a study must be screened carefully for their adherence to basic guidelines and then tested and revised until the researcher feels some confidence that they will be clear to the intended respondents and likely to measure the intended concept (Fowler 1995). Alternative measurement approaches will be needed when such confidence cannot be achieved. Types of Questions Used in Social Research Measuring variables with single questions is very popular. Public opinion polls based on answers to single questions are reported frequently in newspaper articles and TV newscasts. Single questions can be designed with or without explicit response choices. o o closed-ended (fixed-choice) question open-ended questions Closed Ended –survey provides preformatted response categories for the subject to circle or check Closed ended: What is your Ethnicity? 1. Anglo 2.Hispanic 3. African American 4. Asian, 5 Native American Open-ended: respondent replies in his or her own words either by writing or talking Open ended: How would you describe your ethnic background? Making Observations-qualitative Observations can be used to measure characteristics of individuals, events, and places. The observations may be the primary form of measurement in a study, or they may supplement measures obtained through questioning. Direct observations can be used as indicators of some concepts. Observations may also supplement data collected in an interview study. Collecting Unobtrusive Measures Qualitative Unobtrusive measures allow us to collect data about individuals or groups without their direct knowledge or participation. (Can be qualitative or quantitative) Eugene Webb and his colleagues (2000) identified four types of unobtrusive measures: physical trace evidence, archives (available data), simple observation, and contrived observation (using hidden recording hardware or manipulation to elicit a response). Unobtrusive measures can also be created from such diverse forms of media as newspaper archives or magazine articles, TV or radio talk shows, legal opinions, historical documents, personal letters, or e-mail messages. Combining Measurement Operations Using available data, asking questions, making observations, and using unobtrusive indicators are interrelated measurement tools, each of which may include or be supplemented by the others. Researchers may use insights gleaned from questioning participants to make sense of the social interaction they have observed. Unobtrusive indicators can be used to evaluate the honesty of survey responses. Combining Measurement Operations, cont. The choice of a particular measurement method is often determined by available resources and opportunities, but measurement is improved if this choice also takes into account the particular concept or concepts to be measured. Questioning can be a particularly poor approach for measuring behaviors that are very socially desirable, such as voting or attending church, or that are socially stigmatized or illegal, such as abusing alcohol or drugs. People have the tendency to answer questions in socially approved ways. Exhibit 4.9 Triangulation Triangulation—the use of two or more different measures of the same variable—can strengthen measurement considerably. When we achieve similar results with different measures of the same variable, particularly when they are based on such different methods as survey questions and field-based observations, we can be more confident in the validity of each measure. Levels of Measurement When we know a variable’s level of measurement, we can better understand how cases vary on that variable and so understand more fully what we have measured. Level of measurement: The mathematical precision with which the values of a variable can be expressed. (has implications for the type of statistics to be used) The nominal level of measurement, which is qualitative, has no mathematical interpretation; the quantitative levels of measurement— ordinal, interval, and ratio—are progressively more precise mathematically. Nominal Level of Measurement The nominal level of measurement identifies variables whose values have no mathematical interpretation; they vary in kind or quality but not in amount (they may also be called categorical or qualitative variables). Gender is a nominal variable. Nationality, occupation, religious affiliation, and region of the country are also measured at the nominal level. Nominal Level of Measurement, cont. Although the attributes of categorical variables do not have a mathematical meaning, they must be assigned to cases with great care. The attributes we use to measure, or categorize, cases must be mutually exclusive and exhaustive: A variable’s attributes or values are mutually exhaustive if every case has at least one attribute. i.e. Religion: 1.Catholic, 2. Jewish, 3.Protestant, 4. Other The different values of a variable measured at the ordinal level must also be mutually exclusive and exhaustive. variable’s attributes are exclusive when every case can be classified into only one of the categories. Grouped Age: 1.0-20, 2. 21-30, 3. 3140 etc. Ordinal Level of Measurement The first of the three quantitative levels is the ordinal level of measurement. At this level, the numbers assigned to cases specify only the order of the cases, permitting “greater than” and “less than” distinctions. i.e. Heat= 1. low, 2. medium, 3. high Or, if the response choices to a question range from “very wrong” to “not wrong at all”, for example. (Some researchers use this type of ordinal level data as Interval, i.e. Likert Scales) Ordinal Level of Measurement, cont. Of course, an ordinal rating scheme assumes that respondents have similar interpretations of the terms used to designate the ordered responses. This is not always the case, because rankings tend to reflect the range of alternatives with which respondents are familiar. Ugly, Ordinary, Pretty (inbalance in the terms used) Interval Level of Measurement The numbers indicating the values of a variable at the interval level of measurement represent fixed measurement units but have no absolute, or fixed, zero point. The numbers can therefore be added and subtracted, but ratios are not meaningful. Again, the values must be mutually exclusive and exhaustive. This level of measurement is represented by the difference between two Fahrenheit temperatures. We assume equal intervals between attributes. 60 degrees may be 30 degrees hotter than 30 degrees, but 60 degrees cannot be said to be twice as hot as 30 degrees because there is no absolute zero to set up a ratio relationship There are very few true interval-level measures in social science. Interval assumes equal distance between attributes Can’t say between low, medium, high there is equal distance but some use Likert construction as such Likert Scale 1. Very satisfied 2. Satisfied 3. dissatisfied 4. very dissatisfied Notice there is no middle ground i.e. 1. Very satisfied 2. Satisfied 3.satisfied/dissatisfied 4. dissatisfied 5. Very dissatisfied Ratio Level of Measurement The numbers indicating the values of a variable at the ratio level of measurement represent fixed measuring units and an absolute zero point (zero means absolutely no amount of whatever the variable indicates). i.e. Age is continuous (numbers indicating values are points on a continuum For most statistical analyses in social science research, the interval and ratio levels of measurement can be treated as equivalent. On a ratio scale, 10 is 2 points higher than 8 and is also 2 times greater than 5—the numbers can be compared in a ratio. Ratio Level of Measurement, cont. Of course, the numbers also are mutually exclusive and exhaustive, so that every case can be assigned one and only one value. Age is ratio:Ages range in order from 0 to 100 Test scores range in order from 0 to 100 Also people’s ages can be represented by values ranging from 0 years (or some fraction of a year) to 120 or more. A person who is 30 years old is 15 years older than someone who is 15 years old (30 - 15 = 15) and is twice as old as that person (30/15 = 2). Comparison of Levels of Measurement Researchers choose levels of measurement in the process of operationalizing variables; the level of measurement is not inherent in the variable itself. Many variables can be measured at different levels, with different procedures. It is usually is a good idea to try to measure variables at the highest level of measurement possible. The more information available, the more ways we have to compare cases. Measurement Validity Measurement validity refers to the extent to which measures indicate what they are intended to measure. When a measure “misses the mark”—when it is not valid—our measurement procedure has been affected by measurement error. Measurement error can arise in three general ways. Measurement Validity, cont. 1. Idiosyncratic individual errors are errors that affect a relatively small number of individuals in unique ways that are unlikely to be repeated in just the same way. Example: Individuals make idiosyncratic errors when they don’t understand a question, when some unique feelings are triggered by the wording of question, or when they are feeling out of sorts due to some recent events. Measurement Validity, cont. 2. Generic individual errors occur when the responses of groups of individuals are affected by factors that are not “what the instrument is intended to measure.” For example, individuals who like to please others by giving socially desirable responses may have a tendency to say that they “agree” with statements, simply because they try to avoid saying they “disagree” with anyone. Measurement Validity, cont. 3. Method factors can also create errors in the responses of most or all respondents. Questions that are unclear may be misinterpreted by most respondents, while unbalanced response choices may lead most respondents to give positive rather than negative responses. For example, if respondents are asked a question with unbalanced response choices, they are more likely to respond that something is wrong than if they are asked the question with the balanced response choices. Reliability Reliability means that a measurement procedure yields consistent scores when the phenomenon being measured is not changing (or that the measured scores change in direct correspondence to actual changes in the phenomenon). If a measure is reliable, it is affected less by random error, or chance variation, than if it is unreliable. Reliability is a prerequisite for measurement validity: We cannot really measure a phenomenon if the measure we are using gives inconsistent results. Ways to Improve Reliability and Validity Whatever the concept measured or the validation method used, no measure is without some error, nor can we expect it to be valid for all times and places. Remember that a reliable measure is not necessarily a valid measure. Unfortunately, many measures are judged to be worthwhile on the basis of only a reliability test. Conclusions, cont. Statistical tests can help to determine whether a given measure is valid after data have been collected, but if it appears after the fact that a measure is invalid, little can be done to correct the situation, so do pretests. If you cannot tell how key concepts were operationalized when you read a research report, don’t trust the findings. And if a researcher does not indicate the results of tests used to establish the reliability and validity of key measures, remain skeptical.