English Language Learning - Curry School of Education

advertisement

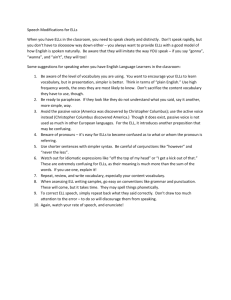

Meeting the Needs of English Language Learners in Reading First Classrooms Today’s Goals Examine the nature of the challenge Identify effective strategies Discuss an action plan at the district, school and classroom levels Learn about Georgia’s ESOL program, regulations, and available resources Some Common Terms and Acronyms Some Common Terms and Acronyms Limited English Proficiency (LEP) English-Language Learner (ELL) English as a Second Language (ESL) English as a Foreign Language (EFL) English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) First (Home) Language (L1) Second Language (L2) Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) The Plight of ELLs How many Englishlanguage learners are in Georgia schools? ? ELLs in Georgia Schools From 1993 to 2004, the number of English language learners in Georgia rose from 11,877 to 59,126 – an increase of 397.8%. Source: National Center for English Language Acquisition More Georgia Stats . . . Public school students in LEP Programs 4.3% Hispanic students 6.9% Asian/Pacific Islander 2.5% Source: NAEP, 2005 Four Types of ELL Programs Type Characteristics Outcome L1-only L1 only is spoken. Children learn to read in L1. (Rare in U.S.) L1 literacy develops, but spoken and written English do not Transitional Bilingual L1 is exclusively used at first, but transition to English is made as soon as possible. L1 literacy jeopardized in transition, but research favors it over English only. Two-way Bilingual Equal time to L1 and English. Half the children speak each. Parents of English speakers desire their children learn L1. (Rare in U.S.) Reading and writing in both languages develop for both groups. English-only (Immersion) Only English is spoken. Teacher provides limited support to ELLs. (Most common program type in U.S.) English slowly develops Reading growth slowed L1 withers since literacy is never attained in L1 – Tabors & Snow, 2002 Four Phases of Transition to Spoken English 1. ELLs use L1, expecting to be understood. – They are often not understood, however. 2. ELLs grow silent. – They realize L1 is not working for them. 3. ELLs begin using telegraphic and formulaic language. – Telegraphic Examples: Object names, counting – Formulaic Examples: Catch phrases (“Excuse me,” “I don’t know”) 4. ELLs gradually learn to use English productively. – They blend formulaic with telegraphic speech Examples: “I do a ice cream,” “I got a big” – Tabors & Snow, 2002 Two Types of Oral English Proficiency What kind is it? What can a child do? Conversational (Social) • Communicate with peers • Use gestures & body language to aid and complement language Academic • Comprehend oral instruction • Comprehend content materials How long does it take to acquire? About 2 years 5-7 years – Adapted from Drucker, 2003 Reading and Language Development of a Native Speaker Foundation of Spoken English Develops Reading Adds to the Foundation Reading Builds on This Foundation Implications for Classroom Instruction So where do teachers start? Most cores have an ELL resource handbook and related materials. Start there. But let’s think about general advice. So where do teachers start? Let’s look at some key differences between Spanish and English. Spanish vs. English Consonants Pronounced the Same c l m n s Pronounced Differently d h j v sh r z Spanish vs. English Consonants Clusters Not Heard in Spanish st sp sk/sc sm sl sn sw tw qu scr spl spr str squ th Spanish vs. English Spanish vowels always have the same sound: English Long a Spanish e Example Pedro Long e Long i Long o i ai o sí jai-lai no Long u Short o u a usted Pablo Spanish vs. English Short vowels are hard for Spanishspeaking children because most of these phonemes do not exist in Spanish! Spanish vs. English What are the implications of these differences for acquiring (and teaching) phonemic awareness and phonics? Phonemic Awareness for Spanish-Speaking ELLs Children’s knowledge of Spanish phonology may influence how they acquire phonemic awareness in English. They may find it hard at first to distinguish phonemes not heard in Spanish (e.g., v-b, s-sp, ch-sh). Instruction in specific pairs has been shown to have positive results. National Literacy Panel on Language-Minority Children, 2006 Phonemic Awareness for Spanish-Speaking ELLs Phonemic awareness in Spanish translates into English. That is, children can do similar tasks (segmenting, blending, etc.). However, the specific phonemes are often different. These differences are predictable. Well-planned teaching leads to equal levels of phonemic awareness for ELLs and native English speakers. Gersten & Geva, 2005 Phonics for Spanish-Speaking ELLs Begin with sounds that English and Spanish share. Start with vowels and consonants that represent sounds that are the same as or similar to the sounds they represent in Spanish (listed in previous slides). Use your knowledge of Spanish to interpret misspellings. (Example: da might be written for the) If you’re not comfortable with Spanish, ask the child to read what s/he has written and listen for letter-sound correspondences. Helman, 2004 Phonics for Spanish-Speaking ELLs A pronunciation error may reflect knowledge of Spanish. Example: Saying seat for sit is common when the child has some reading ability in Spanish. It might also be an attempt to come as close as possible using a Spanish vowel sound. Use low-stress activities to practice pronunciations. Examples: choral reading, echo reading, sound sorting of pictures, poetry, songs Helman, 2004 Phonics for Spanish-Speaking ELLs Try using Venns and word walls to underscore similarities and differences in letter-sound correspondences. (See previous slides.) Developmental spelling inventories can provide useful information about phonics skills (e.g., the one in Words Their Way by Bear et al.). Short vowels should be taught before long vowels. Helman, 2004 Phonics for Spanish-Speaking ELLs Conduct think-alouds comparing English and Spanish. “Teachers may verbalize their thinking in a modeled writing activity as they ponder which sounds they hear in a tricky word. They may even model being confused and selfcorrecting based on a Spanish sound.” (p. 458) Helman, 2004 Which instructional techniques are consistent with theory and research? The Output Hypothesis suggests that teachers provide many opportunities for ELLs to talk and write. Doing so also provides a window on their development of their English. A central way for teachers to assess the learning and understanding of their ELLs is to give them myriad opportunities to write and talk during lessons. When ELLs are silent during extended periods of lesson times, it is not possible to know if or how much they are learning from lessons. – Brock & Raphael, 2005, p. 51 Good instruction for ELLs builds on a long tradition of nesting a reading selection in before, during and after activities. Let’s examine which of the major lesson formats seem most promising. Before During After Major Lesson Formats Directed Reading Activity (DRA) Directed Reading-Thinking Activity (DR-TA) K-W-L Listen-Read-Discuss (L-R-D) Before During After DRA Facts Vocabulary Text structure Students read to complete tasks set by teacher Discussion Writing Before During After DRA Facts Vocabulary Text structure Students read to complete tasks set by teacher Discussion Writing Before During After DRA Facts Vocabulary Text structure Students read to complete tasks set by teacher Discussion Writing Before During After DRA Facts Vocabulary Text structure Students read to complete tasks set by teacher Discussion Writing Before During After 5 Steps in a Classic DRA 1. Background (vocabulary, facts) 2. Focus (set specific purposes) 3. Reading 4. Discussion 5. Skills, Extension, Enrichment 5 Steps in a Classic DRA 1. Background (vocabulary, facts) 2. Focus (set specific purposes) 3. Reading 4. Discussion 5. Skills, Extension, Enrichment Before 5 Steps in a Classic DRA 1. Background (vocabulary, facts) 2. Focus (set specific purposes) 3. Reading 4. Discussion 5. Skills, Extension, Enrichment Before During 5 Steps in a Classic DRA 1. Background (vocabulary, facts) 2. Focus (set specific purposes) 3. Reading 4. Discussion 5. Skills, Extension, Enrichment Before During After DR-TA Before During After DR-TA Facts Vocabulary Text structure Students read to test their own predictions Discussion Writing Before During After DR-TA Facts Vocabulary Text structure Students read to test their own predictions Discussion Writing Before During After DR-TA Facts Vocabulary Text structure Students read to test their own predictions Discussion Writing Before During After K-W-L Before During After K-W-L Students Students read to Discussion brainstorm find out what of what they what they Know they Want to know have Learned Before During After K-W-L Students Students read to Discussion brainstorm find out what of what they what they Know they Want to know have Learned Before During After K-W-L Students Students read to Discussion brainstorm find out what of what they what they Know they Want to know have Learned Before During After L-R-D Before During After L-R-D Teacher fully Students read to presents text complete tasks content set by teacher (Children might listen to Spanish version) Before During Discussion After L-R-D Teacher fully Students read to presents text complete tasks content set by teacher (Children might listen to Spanish version) Before During Discussion After L-R-D Teacher fully Students read to presents text complete tasks content set by teacher (Children might listen to Spanish version) Before During Discussion Writing After Which of these formats seem best suited to the needs of ELLs? DRA DR-TA K-W-L L-R-D Might the issue depend on the age and English proficiency of the child? Which of these general lesson planning formats is used for the selection? How could teachers take that format and increase scaffolding and support for ELLs? What additional materials are provided In your core to support ELLs during needs-based time? Language Experience Approach (LEA) Teacher plans a group experience, such as a field trip, demonstration, etc. Students afterward dictate a passage based on the shared experience. Teacher writes as students dictate. Dictated passage becomes the basis of discussion and a reading lesson. LEA controls for prior knowledge differences, although unpredictable cultural interpretations can occur. – Drucker, 2003 Discussions in Small Groups ELLs are sometimes intimidated into silence in whole-class settings. They are more likely to talk in small groups. Schedule small-group discussions with group make-up including both ELLs and native speakers. – Brock & Raphael, 2005 Shared Reading Teacher reads aloud an enlarged text that all students can see. Students can see text as it is discussed. Teacher can point to key words, etc. Paired Reading Teacher pairs ELLs with native speakers. Students read to each other, with native speaker providing support. Could be tied to repeated readings, where native speaker reads a brief passage and ELL reads the same passage. Building Prior Knowledge Teacher tries to anticipate limitations of prior knowledge. What does the author assume the child knows and that the child may not. Look for ways to build prior knowledge quickly and coherently. – Drucker, 2003 Audio Books Teacher provides a tape of the reading selection, perhaps in a listening center. ELLs follow along as they listen. A minimal level of reading ability is required for this approach to be effective. – Drucker, 2003 Teacher Read-Alouds Read-alouds can be planned with ELLs in mind. 5 steps used by Hickman et al.: 1. Preview story and 3 new words. Give Spanish equivalents. 2. Read the book aloud. Focus on literal and inferential comprehension. 3. Reread, focusing on the 3 words. 4. Extend comprehension, focusing on deeper understanding of words. 5. Summarize the book. – Hickman, Pollard-Durodola, & Vaughn, 2004 Multicultural Books These are likely to require less background building. They build confidence and they value the ELLs’ home culture. Such books make good read-alouds! – Drucker, 2003 Selected Internet Resources Internet TESL Journal http://iteslj.org/ its-online http://www.its-online.com/ English-to-Go http://www.english-to-go.com/ Online Translator http://www.worldlingo.com/en/products_services/ worldlingo_translator.html More Internet Resources Barahona Center http://www.csusm.edu/csb/ Reading Rockets http://www.colorincolorado.org/ Georgia ESOL Program http://public.doe.k12.ga.us/ci_iap_esol.aspx Office of English Language Acquisition (OELA) http://www.ed.gov/about/offices/list/oela/index.html?src=oc National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition (NCELA) http://www.ncela.gwu.edu/ Forming an Action Plan What can we do at the district, school, and classroom levels to meet the needs of ELLs? LEA Schools Teachers LEA Representatives: What resources are available in your community to support ELL children and families? At the District Level Start (or improve) your record keeping system Stay updated on programs http://public.doe.k12.ga.us/ci_iap_esol.aspx Coordinate PD across schools that serve ELLs Lead efforts to attract bilingual teachers Explore transitional bilingual programs Establish active links with the Latino community Recommend that parents turn on captioning Principals and coaches: What resources are available in your school to support ELL children and families? At the School Level Generally, foster cultural awareness Specifically, provide PD in culturally responsive teaching Acquire bilingual and multicultural books Hire bilingual teachers and paraprofessionals Host community-building activities for Latino parents Form teacher study groups Locate and disseminate professional resources At the Classroom Level Seek the Georgia ESOL Endorsement http://www.glc.k12.ga.us/pandp/esol/certif.htm Learn to apply scientifically-based instructional approaches Form needs-based groups with English proficiency in mind Learn conversational Spanish Who me? Learn Spanish? Why not? It will not only help you meet the needs of ELLs, but it will deepen your understanding of English. As the greatest writer in German once put it . . . Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) Those who know nothing of foreign languages know nothing of their own. Suggested Readings Brock, C.H., & Raphael, T.E. (2005). Windows to language, literacy, and culture: Insights from an English-language learner. Newark, DE: IRA. Drucker, M.J. (2003). What reading teachers should know about ESL learners. The Reading Teacher, 57, 22-29. Echevarria, J., & Graves, A. (2003). Sheltered content instruction: Teaching English-language learners with diverse abilities (2nd ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. Echevarria, J., Vogt, M., & Short, D.J. (2004). Making content comprehensible for English learners: The SIOP model (2nd ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. Helman, L.A. (2004). Building on the sound system of Spanish: Insights from the alphabetic spellings of English-language learners. The Reading Teacher, 57, 452-460. Helman, L.A. (2005). Using assessment results to improve teaching for Englishlanguage learners. The Reading Teacher, 58, 668-677. Hickman, P., Pollard-Durodola, S., & Vaughn, S. (2004). Storybook reading: Improving vocabulary and comprehension for English-language learners. The Reading Teacher, 57, 720-730. Suggested Readings Shanahan, T., & August, D. (Eds.). (2006). Developing literacy in Englishlanguage learners. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Tabors, P.O., & Snow, C.E. (2002). Young bilingual children and early literacy development. In S.B. Neuman & D.K. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook of early literacy research (Vol. 1, pp. 159-178). New York: Guilford.