Late 20th-Century Art

advertisement

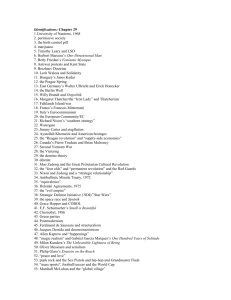

Performance Art: [Dada, Cubist, Surrealist] Happenings (1959-1965) Fluxus (1961-1978) Allan Kaprow (Happenings) Yoko Ono (Fluxus) Performance Art Conceptual Art Yoko Ono, “Snow Piece,” from Grapefruit, Summer 1963 Allan Kaprow, 18 Happenings in 6 Parts (detail), 1959, Reuben Gallery, New York. Kaprow is playing the musical instrument. Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, Switzerland Rose Lee Goldberg traces the contemporary tradition of performance art back to the Futurist and Dada artists before and during the First World War. See: Rose Lee Goldberg’s book Performance Art from Futurism to the Present, 1979, revised and enlarge in 1988. World War I, 19141918, was the first “total war,” fought with bomber planes that carried the battlefield to civilians in the cities of Europe. The total number of casualties in World War I, both military and civilian, were about 37 million: 16 million deaths and 21 million wounded. The total number of deaths includes 9.7 million military personnel and about 6.8 million civilians. Umberto Bocconi, Futurist Evening, 1911 The Allies lost 5.7 million soldiers and the Central Powers about 4 million. City of Ypres, Belgium, after 4 years of “total war” Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, Switzerland Hans Arp, in a 1938 essay titled "Dadaland” recalled how Dada artists integrated all of the arts during the first world war.: “In Zurich in 1915, losing interest in the slaughterhouse of the world war, we turned to the fine arts. While the thunder of the batteries rumbled in the distance, we pasted, we recited, we versified, we sang with all our soul. We searched for an elementary art that would, we thought, save mankind from the furious folly of these times. We aspired to a new order that might restore the balance between heaven and hell. “…Dada aimed to destroy the reasonable deceptions of man and recover the natural and unreasonable order. Dada wanted to replace the logical nonsense of the men of today by the illogically senseless. That is why we pounded with all our might on the big drum of Dada and trumpeted the praises of unreason. Dada gave the Venus de Milo an enema and permitted Laocoön and his sons to relieve themselves after thousands of years of struggle with the good sausage python.... Dada is senseless like nature. Dada is for nature and against art.” Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, Switzerland Hans Arp, in a 1938 essay titled "Dadaland” recalled how Dada artists integrated performance with all of the other art forms during the first world war.: “In Zurich in 1915, losing interest in the slaughterhouse of the world war, we turned to the fine arts. While the thunder of the batteries rumbled in the distance, we pasted, we recited, we versified, we sang with all our soul. We searched for an elementary art that would, we thought, save mankind from the furious folly of these times. We aspired to a new order that might restore the balance between heaven and hell. “…Dada aimed to destroy the reasonable deceptions of man and recover the natural and unreasonable order. Dada wanted to replace the logical nonsense of the men of today by the illogically senseless. That is why we pounded with all our might on the big drum of Dada and trumpeted the praises of unreason. Dada gave the Venus de Milo an enema and permitted Laocoön and his sons to relieve themselves after thousands of years of struggle with the good sausage python.... Dada is senseless like nature. Dada is for nature and against art.” Laocoön, c. 27 BC and 68 AD Venus de Milo, c. 130 and 100 BCE Umberto Bocconi, Futurist Evening, 1911 FUTURISM Hugo Ball performing his poem Karawane, 1:53, 1916 DADA Hugo Ball performing his poem Karawane, 1:53, 1916 DADA Hugo Ball performing his poem Karawane, 1:53, 1916 DADA Costume by Pablo Picasso, for Erik Satie and Jean Cocteau's ballet Parade, Paris, May 1917 Costume of the French Manager for the Ballet “Parade”, 1917 Costume by Pablo Picasso, for Erik Satie and Jean Cocteau's ballet Parade, Paris, May 1917, https://youtu.be/_Chq1Ty0nyE Buckminster Fuller and Merce Cunningham performing in Erik Satie's play The Ruse of Medusa at Black Mountain College, 1948, SURREALISM Costume by Pablo Picasso, for Erik Satie and Jean Cocteau's ballet Parade, Paris, May 1917, https://youtu.be/_Chq1Ty0nyE Buckminster Fuller and Merce Cunningham performing in Erik Satie's play The Ruse of Medusa at Black Mountain College, 1948, SURREALISM Happenings Allan Kaprow first coined the term "happening" in the spring of 1957. Buckminster Fuller and Merce Cunningham performing in Erik Satie's play The Ruse of Medusa at Black Mountain College, 1948, SURREALISM Allan Kaprow, 18 Happenings in 6 Parts (detail), 1959, Reuben Gallery, New York. Kaprow is playing the musical instrument. Kaprow’s first “Happening” was inspired by the experiments at Black Mountain as well as performances that took place in 1957, on a farm belonging to the sculptor George Segal, in New Brunswick, New Jersey. Allan Kaprow, 18 Happenings in 6 Parts (detail), 1959, Reuben Gallery, New York. Kaprow is playing the musical instrument. Kaprow preparing for 18 Happenings in 6 Parts (detail), 1959, Reuben Gallery, New York Entrance to Room 2, 18 Happenings in 6 Parts (detail), 1959, Reuben Gallery, New York Allan Kaprow, 18 Happenings in 6 Parts (detail), 1959, Reuben Gallery, New York. Kaprow is in the white shirt. The audience was given programs and three stapled cards, which provided instructions for their participation: “The performance is divided into six parts... Each part contains three happenings which occur at once. The beginning and end of each will be signaled by a bell. At the end of the performance two strokes of the bell will be heard... There will be no applause after each set, but you may applaud after the sixth set if you wish.” Reenactment of 18 Happenings in 6 Parts (detail), 1959, Reuben Gallery, New York Allan Kaprow, 18 Happenings in 6 Parts (detail), 1959, Reuben Gallery, New York. Kaprow is in the white shirt. After the performance at the Reuben Gallery in 1959, Kaprow wrote an essay about “Happenings” that defined their six key features: A. The line between art and life should be kept as fluid, and perhaps indistinct, as possible. B. The source of themes, materials, actions, and the relationships between them are to be derived from any place or period except from the arts, their derivatives, and their milieu. C. The performance of a Happenings should take place over several widely spaced, sometimes moving and changing locales. D. Time, which follows closely on space considerations, should be variable and discontinuous. E. Happenings should be performed only once. …Aside from the fact that repetition is boring to a generation brought up on ideas of spontaneity and originality, to repeat a Happening at this time is to accede to a far more serious matter: compromise of the whole concept of Change. F. It follows that audiences should be eliminated entirely. All the elements—people, space, the particular materials and character of the environment, time—can in this way be integrated. Allan Kaprow, 18 Happenings in 6 Parts (detail), 1959, Reuben Gallery, New York. Kaprow is in the white shirt. Kaprow, Yard, 1961 Allan Kaprow, 18 Happenings in 6 Parts (detail), 1959, Reuben Gallery, New York. Kaprow is in the white shirt. Kaprow, Yard, 1961 Kaprow, Photoplay (1970, 2008) reinvented at The Santa Monica Museum of Art on April 12, 2008 Fluxus George Maciunas coined the term Fluxus for a proposed magazine in 1961, then wrote this manifesto in 1963. George Maciunas, Fluxus Manifesto, 1963 Kaprow, Photoplay (1970, 2008) reinvented at The Santa Monica Museum of Art on April 12, 2008 Fluxus George Maciunas, Fluxus Manifesto, 1963 Maciunas organized the first Fluxus event in 1961 at the AG Gallery in New York City and the first Fluxus festivals in Europe in 1962. This is his ping-pong table from 1978, using paddles that he created in 1964. https://youtu.be/2-_VmAzicFs, 0:58 George Maciunas, Fluxus Manifesto, 1963 George Maciunas, Fluxus Manifesto, 1963 George Maciunas, Flux Year Box 2, c. 1966, wood box with title screen-printed on lid, containing works by numerous Fluxus artists in the form of small objects, Flux boxes, printe matter, and 8mm films with handheld viewer. A box of matches with label by Ben Vautier, 1966 George Maciunas, Flux Year Box 2, c. 1966, Wood box with title screen-printed on lid, containing works by numerous Fluxus artists in the form of small objects, Flux boxes, printed matter, and 8mm films with handheld viewer. George Maciunas, Fluxus Manifesto, 1963 Fluxus Artists include: George Maciunas Nam June Paik Yoko Ono Joseph Beuys …. George Maciunas, Flux Year Box 2, c. 1966, Wood box with title screen-printed on lid, containing works by numerous Fluxus artists in the form of small objects, Flux boxes, printed matter, and 8mm films with handheld viewer. George Maciunas, Fluxus Manifesto, 1963 Yoko Ono and John Lennon of the Beatles originally published in 1964 Yoko Ono, Sky Machine, 1966 The viewer is invited to climb a white ladder, where, at the top, a magnifying glass, attached by a chain, hangs from a frame on the ceiling. The viewer uses the reading glass to discover a block letter "instruction" beneath the framed sheet of glass-it says "YES." It was through this work that Ono met her future husband and longtime collaborator, John Lennon. Yoko Ono, Ceiling Painting, 1966 Yoko Ono, Liverpool Skyladders, 2008 Yoko Ono, A Hole to See the Sky Through, 1971 Yoko Ono, Telephone Piece, 1964+ “Please answer the telephone when it rings.” Yoko Ono, Bag Piece, 1964, text from MoMA, 2015 Yoko Ono, Bag Piece, 1964 Yoko Ono, Cut Piece, 1965 8:03 Yoko Ono, “Snow Piece,” from Grapefruit, Summer 1963 Yoko Ono, “Snow Piece,” from Grapefruit, Summer 1963