Two Essays on Social Media Usage: The Impact Social Media Mere

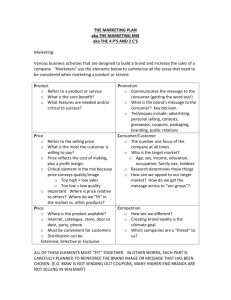

advertisement