A Case of Insulinoma

advertisement

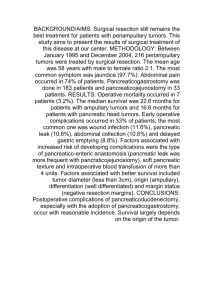

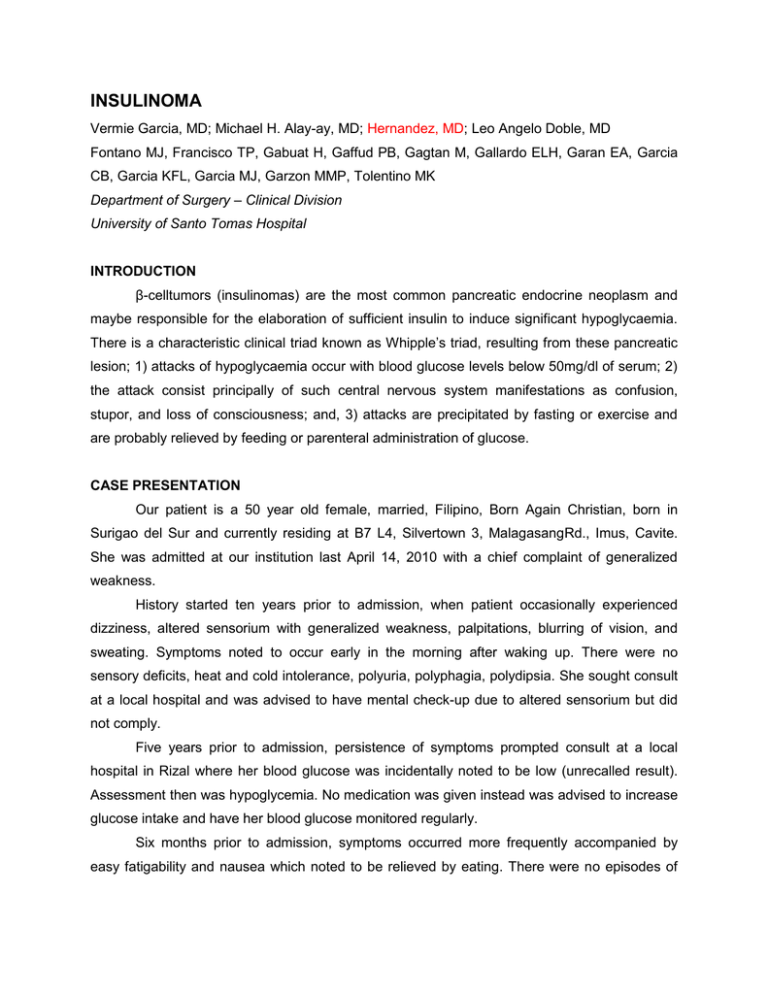

INSULINOMA Vermie Garcia, MD; Michael H. Alay-ay, MD; Hernandez, MD; Leo Angelo Doble, MD Fontano MJ, Francisco TP, Gabuat H, Gaffud PB, Gagtan M, Gallardo ELH, Garan EA, Garcia CB, Garcia KFL, Garcia MJ, Garzon MMP, Tolentino MK Department of Surgery – Clinical Division University of Santo Tomas Hospital INTRODUCTION β-celltumors (insulinomas) are the most common pancreatic endocrine neoplasm and maybe responsible for the elaboration of sufficient insulin to induce significant hypoglycaemia. There is a characteristic clinical triad known as Whipple’s triad, resulting from these pancreatic lesion; 1) attacks of hypoglycaemia occur with blood glucose levels below 50mg/dl of serum; 2) the attack consist principally of such central nervous system manifestations as confusion, stupor, and loss of consciousness; and, 3) attacks are precipitated by fasting or exercise and are probably relieved by feeding or parenteral administration of glucose. CASE PRESENTATION Our patient is a 50 year old female, married, Filipino, Born Again Christian, born in Surigao del Sur and currently residing at B7 L4, Silvertown 3, MalagasangRd., Imus, Cavite. She was admitted at our institution last April 14, 2010 with a chief complaint of generalized weakness. History started ten years prior to admission, when patient occasionally experienced dizziness, altered sensorium with generalized weakness, palpitations, blurring of vision, and sweating. Symptoms noted to occur early in the morning after waking up. There were no sensory deficits, heat and cold intolerance, polyuria, polyphagia, polydipsia. She sought consult at a local hospital and was advised to have mental check-up due to altered sensorium but did not comply. Five years prior to admission, persistence of symptoms prompted consult at a local hospital in Rizal where her blood glucose was incidentally noted to be low (unrecalled result). Assessment then was hypoglycemia. No medication was given instead was advised to increase glucose intake and have her blood glucose monitored regularly. Six months prior to admission, symptoms occurred more frequently accompanied by easy fatigability and nausea which noted to be relieved by eating. There were no episodes of vomiting and abdominal pain noted. She sought consult at a local hospital in Cavite where she was advised to monitor her blood glucose levels, and increase glucose intake. Three months prior to admission, she sought consult at USTH-OPD due to persistence of symptoms and was admitted under the service of Medicine. She then underwent serial fasting glucose determination. However, her first blood glucose level was already 40.5 mg/dL which is below 50 mg/dL (NV: 70.9-110mg/dL), blood insulin level was Figure 1. CT Scan of abdomen 66.83 (NV: 0.275 units of insulin/lb of ideal wt.), C-peptide at 8.1 ng/mL (NV: 0.4-21ng/ml), and HbA1c at 4.9 (NV: 4.5-6%). CT scan was then requested which revealed a well defined enhancing pancreatic body nodule measuring 1.5x1.7x1.6 cms abutting the pancreatic duct (Figure 1). She was advised to undergo surgery prior to discharge but lost to follow up and was seen only on the day of the next admission under the service of Surgery. Review of systems was fairly unremarkable except for weight gain which was approximately 50% after two years. There were no noted abdominal pain, anxiety, black tarry stools, bloatedness, headache, amenorrhea, infertility, anorexia, loss of coordination, mental changes or confusion, muscle pain, nausea and vomiting, sensitivity to the cold and vision problems. Patient’s personal and social history was unremarkable. With regards to her past medical history, she was diagnosed with acute renal failure s/p hemodialysis (3 sessions) in 2005. She also had CAP in 2005 where she was given unrecalled medications. Patient is nondiabetic, no history of PTB, asthma, and allergies. Her family is positive for hypertension, stroke, asthma and liver disease. On admission, the patient was conscious, coherent, ambulatory, not in cardio respiratory distress with stable vital signs. Her weight and height were 88.5 kg and 156cm respectively with a BMI of 36.4 which is considered as obese. She had warm moist skin, no active dermatoses, no jaundice, pink palpebral conjunctiva, anicteric Figure 2. CBG monitoring (mg/dL) on admission (04/15/2010) sclera. There was no tragal tenderness, midline nasal septum and no nasal discharge. Supple neck, no palpable cervical lymphadenopathy and thyroid not enlarged. She had symmetrical chest expansion, no crackles or retractions appreciated, equal and clear breath sounds. Adynamic precordium, AB at 6th LICS AAL, S1>S2 apex, S2>S1 base, no murmurs appreciated. Globular abdomen, NABS, soft, liver span 8 cm R MCL, no palpable mass, no tenderness, (-) Murphy’s sign, (-) CVA tenderness. Pulses full and equal, no cyanosis, no edema. Neurologic examination was unremarkable. On admission, laboratory work-ups from previous admission were correlated with the present complaint. Assessment then was hypoglycemia secondary to hyperinsulinemia to consider insulinoma. Diet consisted of 35 kcal/kg/day (65% CHO, 15% CHON, 25% fat) to address her hypoglycemic episodes. Serial CBG monitoring was continued (Figure 2). Patient was then scheduled for spleen sparing-distal pancreatectomy. Prior to operation, cbc showed normal results while urinalysis revealed pyuria. Blood chemistry showed hypokalemia, 3.22 mmol/L (N:3.8-5mmol/L) and patient was given Kalium durule. ECG showed sinus rhythm with normal tracing however, chest x-ray revealed cardiomegaly. Patient then was given the assessment by CV-Med of minimal to moderate risk of developing perioperative cardiac complications due to cardiomegaly and hypertension stage II. While the patient is on NPO, she was maintained on D5NR 1L to avoid the development of symptomatic hypoglycemia. Two units of packed RBC were prepared and she was given Class 1 ASA risk stratification by the anesthesiology prior to surgery. Patient underwent distal pancreatectomy-spleen sparing procedure last April 20, 2010 (Figures 3, 4 and 5). Intra-operatively a solitary 2.5x2cm mass was palpated at the body of the pancreas (Figure 5). Surgery proceeded first by opening the retroperitoneum at the inferior margin of the pancreas. The splenocolic ligament was then divided and ligated. After which the Figure 3. Head and Body of the Pancreas Figure 4. Spleen Figure 5. A 2.5x2cm mass at the body of pancreas superior mesenteric vein was then followed proximally through the avascular plane as it joins the splenic vein to form the portal vein. The splenic artery was also identified and isolated together with the splenic vein. The pancreas is then divided just to the left of the portal vein and the pancreatic duct was identified and ligated followed by overlapping vertical mattress sutures at the neck of the pancreas. The banches and tributaries of the splenic artery and vein to the pancreas were serially ligated untl the tail of the pancreas was reached and the spleen was preserved (Figure 4). Post-operatively, patient was stable, conscious and not in cardio respiratory distress. Patient’s vital signs, urine output, CBG and the JP drain were carefully monitored. Levemir and Actrapid supplementaion were given as post operative medications to control her blood glucose and insulin levels and was progressed form a diet Figure 6.CBG monitoring post-operatively. of clear liquids to diet as tolerated. Patient had several episodes of hypertension and fever but they were managed cautiously and CBG monitoring continued (Figure 6). She was also reffered to DM Center for instructions on insulin injections. DISCUSSION The pancreas consists of the head, uncinate process, neck, body and tail. The head lies within, and closely attached to, the ‘C’ of the duodenum. The main pancreatic duct (Wirsung) runs the length of the gland. It usually joins the common bile duct at the ampulla of Vater to enter the second part of the duodenum at the duodenal papilla. The accessory duct (Santorini) opens into the duodenum proximal to the main duct. The gland is lobulated and produces the exocrine secretion of digestive hormones from serous-secreting cells, arranged in alveoli. Between these lie the islets of Langerhans, containing A cells (glucagons), B cells (insulin) and D cells (gastrin and somatostatin). It lies in contact with the spleen and runs in the lienorenal ligament. The spleen, in healthy adult humans, is approximately 11 centimetres (4.3 in) in length and usually weighs 150 grams (5.3 oz) and lies beneath the 9th to the 12th thoracic ribs. One of the major function of the pancreas is to secret insulin. The major function of insulin is to counter the concerted action of a number of hyperglycemia-generating hormones and to maintain low blood glucose levels. Because there are numerous hyperglycemic hormones, untreated disorders associated with insulin generally lead to severe hyperglycemia and shortened life span.In addition to its role in regulating glucose metabolism, insulin stimulates lipogenesis, diminishes lipolysis, and increases amino acid transport into cells. Insulinoma is an endocrine tumor of the pancreas derived from beta cells that ectopically secretes insulin, which results in hypoglycemia. The average age of occurrence is 40–50 years. Insulinomas are generally small (>90% are < 2 cm), usually not multiple (90%), and only 5–15% are malignant; they almost invariably occur only in the pancreas, distributed equally in the pancreatic head, body, and tail. The most common clinical symptoms are due to the effect of the hypoglycemia on the central nervous system (neuroglycemic symptoms) and include confusion, headache, disorientation, visual difficulties, irrational behavior, or even coma. Also, most patients have symptoms due to excess catecholamine release secondary to the hypoglycemia including sweating, tremor, and palpitations. Characteristically these attacks are associated with fasting. Insulinomas should be suspected in all patients with hypoglycemia, especially with a history suggesting attacks provoked by fasting or with a family history of MEN-1. The diagnosis of insulinoma requires the demonstration of an elevated plasma insulin level at the time of hypoglycemia. The most reliable test to diagnose insulinoma is a fast up to 72 h with serum glucose, C-peptide, and insulin measurements every 4–8 h. If at any point the patient becomes symptomatic or glucose levels are persistently <2.2 mmol/L (40 mg/dL), the test should be terminated and repeat samples for the above studies obtained before glucose is given. Some 70–80% of patients will develop hypoglycemia during the first 24 h and 98% by 48 h. In addition to having an insulin level >6 µU/mL when blood glucose is <40 mg/dL, some investigators also require an elevated C-peptide and serum proinsulin level, an insulin/glucose ratio >0.3, and a decreased plasma B-hydroxybutyrate level for the diagnosis of insulinomas. Surreptitious use of insulin or hypoglycemic agents may be difficult to distinguish from insulinomas. The combination of proinsulin levels (normal in exogenous insulin/hypoglycemic agent users), C-peptide levels (low in exogenous insulin users), antibodies to insulin (positive in exogenous insulin users), and measurement of sulfonylurea levels in serum or plasma will allow the correct diagnosis to be made. Insulinomas are usually localized with CT scanning and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS). Technical advances in EUS have led to preoperative identification of more than 90% of insulinomas. Arteriography with catheterization of small arterial branches of the celiac system combined with calcium injections (which stimulate insulin release from neoplastic tissue but not from normal islets), and simultaneous measurements of hepatic vein insulin during each selective calcium injection localizes tumors in 47% of patients.Intraoperative transabdominal high-resolution ultrasonography with the transducer wrapped in a sterile rubber glove and passed over the exposed pancreatic surface detects more than 90% of insulinomas.Helical or multislice CT scan has 82-94% sensitivity. In one study, dual-phase helical CT proved more sensitive than single-phase for detection of insulinoma. In patients presenting with signs and symptoms compatible with hypoglycemia with hyperinsulinemia includes reactive hypoglycaemia, functional hypoglycaemia with gastrectomy, adrenal Insufficiency, hypopituitarism, hepatic insufficiency, manchausen syndrome (insulin selfinjections), nonislet cell tumor causing hypoglycaemia, surreptitious administration of insulin or OHAs. In our patient, she presented with signs and symptoms compatible with that of Insulinoma like sympathetic nervous system symptoms resulting from hypoglycemia namely, palpitations, irritability and weakness. The Whipple’s triad were also satisfied with hypoglycemic symptoms produced during fasting, blood glucose levels <50mg/dL during symptomatic attack, and these symptoms were relieved by administration of glucose. MANAGEMENT Conservative management Due to persistently elevated insulin levels, patients will often become hypoglycemic with fasting. To prevent hypoglycemia in these patients, it is advisable to recommend small frequent meals that are rich in carbohydrates. Furthermore, patients should be advised to have a supply of glucose-rich snacks or candies on hand, in case they become symptomatic. It is desirable for these patients to have a meal shortly before sleep and again when waking in the morning. In addition to symptoms from fasting, Whipple's triad includes symptoms during exercise. Therefore, strenuous exercise should be avoided as much as possible. If prolonged physical activity must be undertaken, the patient should have glucose-rich drinks or glucose-rich snacks on hand. The role of drug therapy is primarily in the management of patients with metastatic or unresectable disease or in patients who are not surgical candidates or refuse surgery. For patients in whom a surgical cure has been achieved, there should be no need for further therapy. Medical treatment is indicated when symptoms are not controlled by diet alone. Firstline therapy often consists of diazoxide, a nondiureticbenzothiadiazine. Diazoxide is recognized to stimulate b-cell adrenergic receptors, thus decreasing insulin release, and was used in the medical management of insulinoma since 1963.Chemotherapy is not primarily recommended as a first-line treatment for malignant disease. Despite the sense of urgency that this diagnosis brings, treatment is initially conservative and includes a 3- to 6-month follow-up with ultrasound or CT scan in patients who are medically stable. Further treatment is considered for patients who develop pain, have direct serious effects from the tumor, intractable symptomatology related to excess insulin, or progression of disease. Diazoxide should be used in all patients symptomatic from insulinoma. This group often includes patients awaiting surgery or in whom surgery was unable to localize the primary tumor. Diazoxide plays a substantial role in the palliation of patients with metastatic disease. The standard dose ranges from 150 to 450 mg daily, often divided into doses every 8 hours, but may be increased to as high as 800 mg per day. The drug may be started at low doses and titrated up, depending on the severity of hypoglycemia. Side effects include sodium and water retention and occasionally hirsutism. The concomitant use of a thiazide diuretic is often helpful in managing these effects. Diazoxide can be effective in the symptom management of patients with stable disease. Because most insulinomas are benign, there is often no need for chemotherapy. Furthermore, there may be no need for the use of adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy for treating patients with insulinomas with no evidence of metastatic disease. Surgical Management Most insulinomas are benign and the treatment of choice is surgical resection. The choice of procedure depends on the location of the tumor. The combination of intraoperative ultrasound and palpation can detect the most tumors. Ultrasound can determine the proximity of the tumor to the pancreatic duct. Enucleation of the insulinoma may be performed in patients who have a solitary tumor that is not encroaching on the pancreatic duct hence, it is not done to the patient. Even when preoperative localization is performed, it remains important that the entire pancreas be assessed at the time of surgery. Laparotomy is performed through an upper midline incision or an extended subcostal incision. Access to the pancreas is gained by opening the gastrocolic omentum and entering the lesser sac. The duodenum is widely kocherized and the transverse mesocolon is separated from the inferior border of the pancreas. This separation allows for examination and bimanual palpation of the entire pancreas. If necessary, the spleen may be mobilized from its lateral attachments to allow complete delivery of the pancreatic body and tail for inspection and palpation. Insulinomas are often small, round, and reddish-brown nodules and solitary. If it is determined with the aid of intraoperative ultrasound that tumor enucleation can be performed safely, this is the procedure of choice for tumors to the right of the superior mesenteric vein. A Whipple procedure (pancreaticoduodenectomy) is rarely necessary, but it may be required if the tumor is in close proximity to major ductal structures. In general, distal pancreatectomy is performed en-bloc along with resection of the spleen. Most of the time, the en-bloc pancreatic-spleen resection is performed for technical reasons, it makes the operation short and easy but does not offer any special advantage for the patient (Cruz, et al). There is no real consensus on the need to perform spleen preservation in the setting of a malignant neoplasm. In the large series of 235 distal pancreatectomies reported by Lillemoe et al., only 49 patients (21%) underwent resection for adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. They always recommend an en-bloc distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy. AndrénSandberg et al., also believe that splenectomy should be routinely performed because splenic artery preservation is hazardous for oncologic radicality when distal pancreatectomy is performed for cancer. However, this argument should not be used against preservation of the spleen. Involvement of the splenic vein, and the splenic artery distant from the coeliac axis, is frequently found, and does not preclude distal pancreatic resection for malignant tumours in the body-tail of the pancreas. Mobilization of the caudal surface of the body of the pancreas from the retroperitoneum is performed after division of the splenic artery close the coeliac trunk, followed by division of the splenic vein close to the junction to the mesenteric vein. It allows an extensive retroperitoneal lymph node dissection. The spleen may be preserved by maintaining the integrity of the short gastric vessels and the left gastro-epiploic vessels (Warshaw's technique). According to Balcom et al., spleen-sparing distal pancreatectomy may also be preferable in the setting of a malignant neoplasm not directly involving the spleen because it is a putative mechanism for maintenance of immune surveillance. Also, for Sasson et al., whenever possible, splenic conservation should be attempted in patients undergoing total or distal pancreatectomy for adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Schwarz et al. have studied the impact of splenectomy on hospital stay and survival after resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. In this analysis, splenectomy has no significant measurable impact on postoperative recovery, but has a negative influence on long-term survival independent of disease-related factors. The authors concluded that splenectomy should be avoided in the operative treatment of exocrine pancreatic cancer at any localization. The French surgeon Mallet-Guy first described, in the 1940s, the technique of spleenpreserving pancreatic left resection for patients with chronic pancreatitis. Since that time, the reasons why spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy was performed or not performed, are not clear in the literature. In some reports, the incidence of splenic preservation was rather low at 20%, as reported by Rattner et al., and 24% as reported by Sakorafas et al. In some other reports, including our series, the spleen was salvaged successfully in 31–57.9% of cases . The main reason for performing pancreatic left resection with splenectomy is the finding of pancreatic tissue firmly and densely adherent to the splenic vessels. The en-bloc distal pancreatic-spleen resection is mostly performed for technical reasons, to make the operation short and easy, as compared with spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy, a technically demanding and more time-consuming procedure. We believe that—even in cases of severe chronic pancreatitis followed by gross pancreatic calcification, marked oedema and fibrosis that also encase the splenic vessels—spleen-sparing distal pancreatectomy should be encouraged, applying the Warshaw's technique with preservation of the short gastric vessels. In other cases, the oedema resulting from chronic inflammation surrounding the splenic vessels may facilitate splenic vessel preservation and splenic conservation. In the Johns Hopkins's series the incidence of pancreatic fistula after enucleation was reported to be 50%. Recently, Kiely et al. have introduced some major operative modifications, the introduction of intraoperative ultrasound imaging to identify the pancreatic duct and closure of the pancreatic defect after enucleation. In this series, despite these refinements in the technique, the pancreatic fistula rate was 27%, and the hospital stay was 12.6 days. Tumour enucleation does not address the malignant potential of these tumours and should be used (in selected cases) with caution to avoid inadequate tumour margins. In the literature, when the tumour was located in the body or tail of the pancreas, the technique most frequently used was distal pancreatectomy. In some series, it was not stated whether there was conservation of the spleen at the time of distal pancreatectomy. Insulinomas in the neck, body, and tail of the gland not amenable to enucleation are treated with spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy . Solitary tumors in the neck or body of the pancreas that are not amenable to enucleation may also be treated by median pancreatectomy. In this procedure, the pancreas is exposed. The superior mesenteric and portal veins are dissected from the posterior pancreas and the splenic vessels are preserved. The tumor is resected with a 1-cm margin on either side. The proximal stump of the pancreas is closed with interrupted sutures or a stapler, whereas the distal stump is anastamosed to a Roux-en-Y loop similar to the distal pancreas in a pancreaticoduodenectomy. This procedure prevents the morbidity of a duodenal and common bile duct resection, thus still preserving the distal pancreas. The spleen plays a crucial role in the body's ability to fight off bacteria, living without the organ makes a person more likely to develop infections, especially dangerous ones such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Haemophilus influenzae. These bacteria cause severe pneumonia, meningitis, and other serious infections. Vaccinations to cover these bacteria should be given in patients without a spleen. Infections after spleen removal usually develop quickly and make the person severely ill. They are referred to as overwhelming post-splenectomy infections, or OPSI. Such infections cause death in almost 50% of cases. Children under age 5 and people who have had their spleen removed in the last two years have the greatest chance for developing these life-threatening infections. Other complications related to splenectomy include blood clot in the vein that carries blood to the liver, hernia at the incision site, infection at the incision site, pancreatitis, lung collapse and injury to the pancreas, stomach, and colon. The major morbidities of these operations include pancreatic fistula and persistent hyperinsulinism for all procedures, bile leak and prolonged gastric ileus for pancreaticoduodenectomy, and injury to the spleen necessitating splenectomy. Mortality from the largest of operations can be kept to below 4%. If the tumor cannot be found or if high insulin/low glucose levels persist after tumor removal, the patient needs to be sent to a center of excellence for further imaging and reoperation. Blind distal resection is not indicated. In patients with multiple tumors (MEN-1), a modified approach should be taken. The pancreas should be exposed and fully evaluated. Multiple tumors are often present in the tail and body of the pancreas, necessitating a distal pancreatectomy. Any remaining tumors in the head of the pancreas can be managed with enucleation. This approach does increase the risk of postoperative diabetes, but it is the only true chance for a surgical cure. Additionally, one group has described inserting a catheter into the portal vein through the umbilical vein. They injected 0.025 mEq/kg of calcium gluconate and sampled portal venous blood at 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 seconds after injection. When no rise in serum insulin levels were found, they were satisfied that no insulinoma tissue remained.The patient with malignant disease poses a more complex management problem. Patients with a curative resection for malignancy have roughly a 50% chance of disease-free survival at 3 years and an absolute survival advantage over patients with a palliative resection. In patients without diffuse disease, there is more than a 60% 5-year survival rate and an approximately 30% 5-year survival rate in patients with diffuse disease.Therefore, the recommendation would be to resect the primary tumor if possible, along with any other resectable metastatic disease and involved lymph nodes. In the later stages of disease, debulking surgery has a definite role to play in palliation of symptoms. Other techniques, such as cryoablation, or resection of hepatic metastases can offer substantial palliation. Laparoscopic pancreatic surgery may find increasing use in the management of patients with insulinoma. Laparoscopic resection was described in 1996 and is a viable method of therapy. REFERENCES Distal pancreatectomy: en-bloc splenectomy vs spleen-preserving pancreatectomy Laureano Fernández-Cruz, David Orduña, Gleydson Cesar-Borges, and Miguel Angel López-Boado. Department of Surgery, Hospital Clinic i Provincial de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain Lillemoe KD, Kaushal S, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, Pitt HA, Yeo CJ. Distal pancreatectomy: indications and outcomes in 235 patients. Ann Surg. 1999;229:693–8. Andren-Sandberg A, Wagner M, Tihanyi T, Lofgren P, Fries H. Technical aspects of left-sided pancreatic resection for cancer. Dig Surg. 1999;16:305–12. Balcom JH, 4th, Rattner DW, Warshaw AL, Chang Y, Fernández-del Castillo C. Ten-years experience with 733 pancreatic resections: changing indications, older patients, and decreasing length of hospitalization. Arch Surg. 2001;136:391–8. Sasson AR, Hoffman JP, Ross EA, Kagan SA, Pingpank JF, Eisenberg BL. En bloc resection for locally advanced cancer of the pancreas: is it worthwhile? J Gastrointest Surg. 2002;6:147–57. Schwarz RE, Harrison LE, Conlon KC, Klimstra DS, Brennan MF. The impact of splenectomy on outcomes after resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188:516–21. Sarr MG, Carpenter HA, Prabhakar LP, Orchard TF, Hughes S, van Heerden JA, et al. Clinical and pathologic correlation of 84 mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: can one reliably differentiate benign from malignant (or premalignant) neoplasms? Ann Surg. 2000;231:205–12 Thompson LDR, Becker RC, Prygodzki RM, Adair CF, Heffess CS. Mucinous cystic neoplasm (mucinous cystadeno-carcinoma of low grade malignant potential) of the pancreas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:1–6. Zamboni G, Scarpa A, Bogina G, Iacona C, Bassi C, Talamini G, et al. Mucinous cystic tumors of the pancreas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:410–22. Pyke CM, van Heerden JA, Colby TV, Sarr MG, Weaver AL. The spectrum of serous cystadenoma of the pancreas. Clinical, pathologic, and surgical aspects. Ann Surg. 1992;215:132–9. Talamini MA, Moesinger R, Yeo CJ, Poulose B, Hruban RH, Cameron JL, et al. Cystadenomas of the pancreas: is enucleation an adequate operation? Ann Surg. 1998;227:896–903. Kiely JM, Nakeeb A, Komorowski RA, Wilson SD, Pitt HA. Cystic pancreatic neoplasms: enucleate or resect? J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:890–7. Meyer W, Kohler J, Gebhardt C. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas – cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas. Langen-becks Arch Surg. 1999;384:44–9. Le Borgne J, de Calan L, Partensky C. Cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas of the pancreas: a multiinstitutional retrospective study of 398 cases. French Surgical Association. Ann Surg. 1999;230:152– 61. Shima Y, Mori M, Takakura N, Kimura T, Yagi T, Tanaka N. Diagnosis and management of cystic pancreatic tumours with mucin production. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1041–7. Mallet-Guy P, Vachon A. Masson; Paris: 1943. Pancreatites chroniques gauches. Rattner DW, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Warshaw AL. Pitfalls of distal pancreatectomy for relief of pain in chronic pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1996;171:142–5. Evans JD, Morton DG, Neoptolemos JP. Chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma. Postgrad Med J. 1997;73:543–8. Schoenberg MH, Schlosser W, Ruck W, Beger HG. Distal pancreatectomy in chronic pancreatitis.Dig Surg. 1999;16:130–6. Govil S, Imrie CW. Value of splenic preservation during distal pancreatectomy for chronic pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1999;86:895–8. Sakorafas GH, Sarr MG, Rowland CM, Farnell MB. Post-obstructive chronic pancreatitis: results with distal resection. Arch Surg. 2001;136:643–8. Bauer A, Uhl W, Tcholakov O, Wagner M, Friess H, Böchler MW. Böchler MW, Friess H, Uhl W, Malfertheiner P. Blackwell; UK: 2002. Pancreatic left resection in chronic pancreatitis – indications and limitations, Chronic pancreatitis – novel concepts in biology and therapy; pp. 529–39. Fernandez-Cruz L, Saenz A, Astudillo E, Pantoja JP, Uzcategui E, Navarro S. Laparoscopic pancreatic surgery in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:996–03. Hutchins RR, Hart RS, Pacifico M, Bradley NJ, Williamson RC. Long-term results of distal pancreatectomy for chronic pancreatitis in 90 patients. Ann Surg. 2002;236:612–18. University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Medicine and Surgery A Case of Insulinoma Group 5 Fontano, Michael Jeff B. Francisco, Therese Pauline D. Gabuat, Harry M. Gaffud, Prima Bianca N. Gagtan, Majelle L. Gallardo, Estee Laurence Heart C. Garan, Elizabeth Aileen L. Garcia, Cholson Banjo E. Garcia, Kristina Fatima Louise P. Garcia, Mark Jesreel O. Garzon, Maria Monica Pamela N. Tolentino, Maria Kariza L.