- The University of Liverpool Repository

advertisement

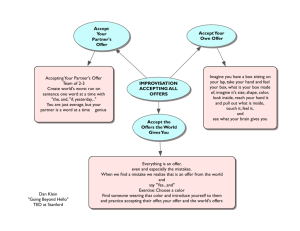

Improvisation Processes in Organizations Miguel Pina e Cunha Nova School of Business and Economics Universidade Nova de Lisboa Portugal mpc@novasbe.pt Anne S. Miner University of Wisconsin – Madison USA aminer@bus.wisc.edu Elena Antonacopoulou GNOSIS University of Liverpool Management School UK E.Antonacopoulou@liverpool.ac.uk Chapter 38 in A. Langley and H. Tsoukas (Eds) (2015) SAGE Handbook of Process Organization Studies. Sage: London. 1 Bios Miguel Pina e Cunha is professor of Organization Theory at Nova School of Business and Economics, Lisbon, Portugal. His research has been published in journals such as the Academy of Management Review, Human Relations, Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, Journal of Management Inquiry, Journal of Management Studies, Journal of Product Innovation Management, Leadership Quarterly, Organization, and Organization Studies. He recently co-authored, with Arménio Rego and Stewart Clegg, “The virtues of leadership: Contemporary challenge for global managers” (Oxford University Press, 2012). Anne S. Miner is Professor of Management and Human Resources Emeritus at the Wisconsin School of Business. Miner studies organizational learning and improvisation, including papers on improvisation in product development and organizational learning from failure. Miner was named 2004 Scholar of the Year by the Technology and Innovation Management Division of the Academy of Management. She has served as associate editor of Management Science and of Organization Science, and on the editorial boards of Administrative Science Quarterly, the American Sociological Review, the Academy of Management Journal, the Academy of Management Review, and Strategic Organization. Miner’s B.A. is from Harvard, and her Ph.D. from Stanford. She has also worked as VP of a start-up and as assistant to the President at Stanford. Elena Antonacopoulou is Professor of Organizational Behavior at the University of Liverpool Management School, where she leads GNOSIS - a research initiative advancing impactful collaborative research in management and organization studies. Her principal research expertise lies in the areas of Organisational Change, Learning and Knowledge Management with a focus on the Leadership implications. Her research continues to advance new methodologies for studying social complexity and is strengthened by her approach; working with leading international researchers, practitioners and policy-makers collaboratively. Her current study on ‘Realizing Y-Our Impact’ is one example of the approach that governs her commitment to pursue scholarship that makes a difference through actionable knowledge. Elena’s work is published widely in leading international journals and edited books. She has been elected in several leadership roles and has served her scholarly community as a member at Board, Council, Executive and Editorial roles of the top professional bodies (AoM, EGOS, EURAM, SMS etc) 2 What do disaster workers and units, SWAT officers and film crews, Soviet special troops, firefighters and medical doctors, IT workers and bank tellers, have in common? How can large firms, governments and start-ups end up with a deliberate strategy that was not planned in advance? How do ordinary organizational actors get things done? According to organizational research, they all improvise. This chapter reviews the literature on improvisational processes, including gaps and frontiers for future research, and suggests that Improvisational processes offer a vital framework for further probing organizing processes. We organize our review in three main sections. First, we present a basic working definition of improvisation, and explore contemporary assumptions about its pervasiveness and impact. Second, we describe four stylized forms of improvisational processes described in the literature. We arrange the forms using two conceptual axes: the absence/presence of a common goal and micro/macro (individual vs. collective). These axes represent oversimplifications of the ongoing flow of organizational life, but help group prior research. We then describe research on interactions between improvisational levels and other processes. Finally, we consider gaps and promising frontiers for future research on improvisational processes as a core element of organizing. Definition and key assumptions Improvisation is itself a process. To assess whether or not improvisation has occurred, it is not enough to look just at a static outcome. One must also look at the order of activities occurring over time. In the improvisation process, the design of a novel activity pattern occurs during the pattern’s enactment. This contrasts with 3 classic management theory where actors analyze, make decisions, and then act. The improvisation processes differ, then, from both fully pre-planned activity, and from replicating the stable content of a routine. Researchers sometimes highlight different aspects of improvisation, but the minimal formal definition of this process involves three conceptual dimensions (Cunha et al., 1999; Miner et al., 2001; Moorman & Miner, 1998a). These include the convergence of design and performance (extemporaneity), the creation of some degree of novel action (novelty) and the deliberateness of the design that is created during its own enactment (intentionality). The process often involves working with an improvisational referent (Miner et al., 2001), which might be a prior version of an action pattern or prior plan. The definition implies that improvisation represents a special type of innovation. However, the content of an innovation can be planned in advance, so not all innovation activity represents improvisation. This definition also implies that improvisation represents a special type of unplanned action: it involves a deliberate new design, so excludes random change. Thus not all unplanned action is improvisation. The condensed articulation of these three dimensions results in a minimalist definition of pure improvisation as the deliberate and substantive fusion of the design and execution of a novel production. Some improvisation research has focused especially on the degree of extemporaneity in activity, and other work focuses on the degree of novelty, but some degree of both is required for an activity to match this definition. Without this, improvisation collapses into the already-developed domains of innovation and organizational change. Throughout this chapter, when we refer to 4 organizational actors we include individuals, teams, units, and entire organizations (Cunha et al., 1999), even while recognizing that these artificially concrete entities can themselves represent ongoing constructions of many processes. Pervasiveness of improvisation. Two lines of thinking about improvisation’s pervasiveness have crystallized to-date. At one end of the spectrum, researchers highlight that the enactment of even stable routines or plans involves more than repetition: it often involves the extemporaneous embellishment of daily practice. The organizational actor engages in a flow of activity (Orlikowski, 1996; Tsoukas & Chia, 2002) and tailors the design of action to a specific concrete setting. This can represent an ongoing re-constitution of a prior pattern in a unique response in time and space (Antonacopoulou, 2008). From this perspective improvisation can be seen as part of most performative activity (Feldman & Pentland, 2003). As March argues (1981, p. 564), “most of the time most people in an organization do what they are supposed to do; that is, they are intelligently attentive to their environments and their jobs.” To the degree that this means adjusting prior action templates for each context, improvisation is pervasive. At the other end of the spectrum, important theoretical traditions envision much organizational life as enacting routines, and scripts, norms, traditions or habit (Cyert & March, 1963), or as planning, analyzing, deciding and then acting (March, 1976; Mintzberg, 1994). Even though routines and regularities in action patterns can represent effortful achievements, -- not detached objects, -- improvising differs from the execution of stable elements of routines. It involves some degree of novel performance relative to a referent (Crossan, 1998; Baker et al., 2003). It also differs 5 from planning and then acting because it involves design during, not before, performance. When the changes to a plan or stable pattern are substantial, improvisation represents an unusual activity. Although at first glance these visions seem contradictory, current research suggests that both visions have authenticity and important promise. Extant descriptive research supports Weick’s observation that much organizational life can be seen as a “mixture of the pre-composed and the spontaneous” (Weick, 1998, p. 551). Both traditions offer doorways to explore how different mixtures of predesigned and spontaneous activities occur and why they matter. Impact of improvisation. Contemporary researchers broadly agree that improvisation can produce mixed results. Historically, two undercurrents have influenced improvisation theory. Traditional normative efforts to improve managerial practices promoted replacing improvisation with smarter planning and better routinization, whether in Taylor’s Scientific Management, TQM, process-reengineering or strategic planning. This approach underlies even practice-oriented fields such as manufacturing operations, marketing and disaster management. Theorists often assume that planning and/or routinization trumps other approaches even more under conditions of stability. At the same time, however, careful observers have long argued that emergent, unplanned and non-routine processes can have value especially in dynamic settings (March, 1976; Mintzberg, 1994). Perhaps partly to overcome the historical antiimprovisation undertow, some early improvisation research portrayed it primarily as a source of flexibility, speed and adaptation. Observation of improvisation in practice, 6 however, led to the rejection of any unconditional impact, -- either valuable or harmful. Much research now focuses on contextual features that influence its occurrence or impact (Cunha, Neves, Clegg & Rego, forthcoming; Hmieleski et al., 2013; Magni et al., 2009). The assumption of mixed potential value has helped spur emerging theories about whether, when and how different contexts promote the value of improvisational activity, both short-term and long-term. Improvisation’s impact is seen as involving trade-offs (Vera et al., 2014) and dialectical sub-processes (Weick, 1998; Clegg, Cunha & Cunha, 2002). For example, the relative balance of structure and freedom is assumed to play a key role. Improvisation in the absence of structure can potentially lead to strategic drift or even dangerous lack of coordination (Bigley & Roberts, 2001; Ciborra, 1999). At the same time, the lack of freedom can introduce structural rigidity (Brown & Eisenhardt, 1997; Gong, Baker & Miner, 2009). Improvising over minimal structures can offer a chance to avoid both risks, and is often presented as a backbone of effective improvisational action (Kamoche & Cunha, 2001). Other work emphasize the value of organizational memory (Moorman & Miner, 1998a; Kryiakopouous & Klien, 2000) or of routinized activities that can be recombined in improvisational bricolage (Baker & Nelson, 2005), increasing its effectiveness. Four Modes of improvisation We organize extant streams of research through two conceptual axes: (1) the absence/presence of a common goal, and (2) level of analysis (micro/macro). Although clearly oversimplying the ongoing flow of action, the two axes offer a useful heuristic to organize work to date, and they flag coherent issues for future research. 7 They help capture work done in different disciplinary approaches and with diverse degrees of maturity. Based on these axes we identify four modes of improvisation: 1) Micro improvisation as ad hoc action to accomplish work, 2) Macro improvisation as strategy, 3) Micro improvisation as political ingenuity and 4) Macro improvisation as struggle for strategic domination. We discuss them below in that order. Improvisation in pursuit of a common purpose Micro improvisation as ad hoc action to accomplish work. At least three stylized versions of this basic form appear in extant research. Baseline improvisation as part of practice. Improvisation process researchers argue that even when organizational actors see themselves as executing familiar routines, or following plans, they inevitably must tailor their action to the specific context and time. We refer to this form of improvisation as baseline improvisation, in the spirit of a basal metabolism rate that is required for a system to operate at all. This type of improvisation is often seen as being nearly ubiquitous whenever action is taken and is a natural part of practice (Antonacopoulou, 2008; Orlikowksi, 1996). At least some of the activities in an action pattern are novel because they are distinct from prior enactments, due to the unique context. Resolution of unexpected events or problems. Organization actors also regularly deal with unexpected events, or with unexpected ‘real life situations” (Jarzabkowski & Kaplan, 2014). Actors may conclude that a surprise requires an immediate, novel response in order to get things done (Bechky & Okhuysen, 2011; Cunha et al., 2006). Spontaneous improvised corrective action can thus emerge (Crossan & Sorrenti, 1997) and work as a fundamental mechanism of adjustment to keep organizations going. 8 Action template re-design. Finally, actors sometimes make major changes to prior plans or routines during execution, altering at least one core feature above and beyond what it takes to match action to a local context (Miner et al., 2001). This form of improvisation is not inevitable, and can vary in how much deviation occurs when compared to prior action templates (Vera & Crossan, 2005; Weick, 1998). It is often discouraged in modern, formal organizational life. Even emergency workers who acknowledge the potential value of constrained improvisation nonetheless discourage what they call “freelancing” (Bigley & Roberts, 2001) because it can risk lives due to coordination challenges. In all three of these forms of micro-improvisation, improvisers are motivated by the common purpose of “’getting the job done’ in an institutionally complex present” (Smets et al. 2012, p. 894). In baseline improvisation they routinely adjust action to context while acting (Yanow & Tsoukas, 2009), making some form of improvisation a normal feature of organizations life (Ciborra, 1999: 78). In other cases, significant adjustments occur, sometimes in response to major problems (Weick, 1993; Kendra & Wachtendorf, 2003). The improvising actors may reflect while acting (Schon, 1983), but the degree of explicit mindfulness can vary. Actors also adjust through planning new activities, of course, making the improvisation’s relative presence a salient issue. The more radical the changes embedded in an improvised design, the more coordination challenges arise. Considerable research indicates that attention to realtime information and dialectic interactions between actors can help overcome some improvisational coordination challenges (Crossan, 1998; Kyriakpolous & Klein, 2011; Moorman & Miner, 1998a). 9 Field studies of improvisation have revealed three features of such micro improvisation with relatively untapped potential for process research, however. First, even during emergencies, actors sometimes ignore surprises, or stop or make new plans (Bechky & Okhuysen, 2011). Thus theorizing will match observed processes more precisely if it explores when surprises do or do not prompt improvisation. Second, organizational actors sometimes improvise to take advantage of unexpected opportunities (Weick, 1998; Miner et al., 2001), not just to deal with problems. In some intriguing cases, the same event can begin as a problem but become a perceived opportunity (Weick, 1998; Miner et al., 2001; Vera & Crossan, 2005). Thus theory will also match observed organizational life more precisely if it addresses both problems and opportunities as potential triggers. Finally, field studies reveal that organizational actors sometimes improvise in a spirit of play or in pursuit of transcendence, even in work settings (Hatch, 1997). Exploring whether this motivation for improvisation spurs distinct outcomes offers a promising, still-undertheorized issue. Macro-improvisation as strategy Another body of work has focused on improvisation as a process operating at a macro or strategic level of analysis (Baker et al., 2003; Brown & Eisenhardt, 1997; Yanow & Tsoukas, 2009). The first sub-set of this work describes discrete improvised strategic actions. Traditional strategy research assumes that firms plan in advance before enacting a strategic action such as a merger, adoption of a market strategy, investment in a new technology, or change in core goals (Mintzberg, 1994). A discrete strategic improvisation refers to the process when an organization deliberately enacts a specific strategic action without planning it in advance. Bingham (2009), for 10 example, describes how some firms improvise foreign market entry. The launch of Virgin Airways represents an iconic popular example. The second major stream of work describes organizations engaging in strategic processes that embrace improvisation in an ongoing way. Eisenhardt and Tabrizi, (1995, p.106) argue that (strategic) “…decision makers avoid planning, because it is a futile exercise when the environment is changing rapidly and unpredictably.” Brown and Eisenhardt (1997) propose that organizations can benefit from improvisational processes when their environment changes deeply and rapidly. The logic here also holds for developing strategies without routinized stocks of organizational practices (Bingham, 2009; Gong, Baker & Miner, 2006). This work has flagged several conditions argued to promote strategic improvisation’s effectiveness. These include the use of simple rules that allow actors to improvise within structural designs that synthesize freedom and order, and cultivating heuristics, which offer enough consistency for efficiency but also flexibility to match unique aspects of particular opportunities (Bingham & Eisenhardt, 2011). Employees at the boundary can actively participate in the process, sensing and transmitting environmental information with potential strategic value (e.g. see Ton, 2014). Strategy, in this perspective, is a co-evolutionary process of constantly adjusting to a changing environment via incessant improvisation within some structure and consistency. The third stream of strategy-related work emphasizes that organizations can show competencies in improvisation itself, which they rely on as part of their enduring style of action. Gong et al. argue (2005, p.29) that: “…firms sometimes solve classes of repeated problems by persistently improvising solutions. ” Baker et al. (2003) called such capabilities “improvisational competencies.” When an organization feels 11 sufficiently confident about its improvisational competence, it may improvise macro organizational activities such as restructuring (Bergh & Lim, 2008). In this situation, the organization does not repeat a specific new action pattern designed during a discrete improvisational incident. Instead, it repeats the improvisation process itself. The organization may develop practices such as making internal real-time communication easier to support anticipated repeated improvisation (Gong et al., 2005 ). Such improvisational competencies can become a macro foundation of organizational advantage. The vision of improvisational competencies is also consistent with improvisation as a process conducted in a dispersed way by communities of practitioners, -- whether within a focal organization or profession -- who act face-toface with operational problems (Charles & Dawson, 2011). Gong et al. (2005) argue, however, that such capabilities can also represent a competency trap. The organization improvises when prior planning would have avoided serious execution problems. Improvisation in the absence of shared common purpose Micro improvisation as political ingenuity One form of accepted potential differences between parts of organizations, consists of actors lower in authority structures versus the interests or actions of others at higher levels in the structure. The organizational “underlife” (Manning, 2008) is a space where informal experiments are conducted, outside the formal organization’s scope of attention or outside of higher level formal observers of a given actor or unit. Miller and Wedell-Wedellsborg (2013) argue that improvisation can play a role in 12 efforts to hide actions “below” the formal organization. It can enable deviations from the organization’s directives in a subtle manner (Crozier & Friedberg, 1976). Actors may protect desirable professional identities around carefully maintained improvisational expressions of independence, for example favoring improvisation over formalized procedures (Orr, 1990). Activities are transmitted via “hidden transcripts,” and discourses stabilize “beyond direct observation of those in power” (Dailey & Browing, 2014, p.28). Underlife is not necessarily improvisational. Actors can also make hidden plans or follow stable parts of hidden routines outside the observation of formal authority systems. Nonetheless improvisation can play a key role in underlife processes. One important stream of evidence appears in the innovation literature. Innovators sometimes improvise during their discovery projects and hide these activities from formal scrutiny. In some cases, they conduct experiments in a highly improvisatory way (i.e. enacting the development on the spot without prior planning, bricolaging) but also shield these improvisational experiments, to avoid premature assessment or opposition. Micro-improvisation as political ingenuity goes beyond the assumption that individual actors pursue individual self-interests that diverge from formal goals (Balogun & Johnson, 2004; Mantere & Vaara, 2008). It also includes processes in which subgroups have different foci of attention based on different contexts for their experience. Actors also engage in the symbolic management of the degree of improvisation in their own work. They can “choose their designs carefully to present some details as new, others as old, and hide still others from view altogether” (Hargadon & Douglas, 2001, p.499). 13 As with other forms of improvisation, observers argue that prior experience can affect the resources available as part of political ingenuity. For example, de Certeau (1984, p. 23) argues that, as people gain experience with the inner workings of a system, they develop a firsthand understanding of the actions possible within such a system. The re-playing of a game changes the understanding of its rules and opens new possibilities. Such schemas of action represent one vocabulary available for microimprovisational activities. Macro improvisation as struggle for strategic domination Although less well developed than the areas above, descriptions of improvisation also appear in studies of guerrilla warfare, revolutions and social movements, even though traditional normative theories of warfare, internal power struggles and social change focus developing better strategic plan and acquiring resources. Domination in this context can refer to changing an organization’s identity, absorbing its resources, changing its core goals or seeking its total annihilation. Explicit warfare. Strategic guerilla warfare has long stressed improvisational activity. Improvised surprise attacks are easier to coordinate with smaller groups, and sometimes harder for larger groups to respond to (Guevara, 2002). As is the case inside organizations, improvisation makes it less likely that actions can be thwarted by the larger power, although plans for guerilla actions can also be designed in advance. Control of powerful opponents. Saul Alinksy (1971; 2010) describes sequences of improvisational actions involved in the pursuit of control of other organizations. In real time during a struggle, Alinsky and his colleagues improvised by using proxy votes as a way to get publicity and affect corporate policies. The initial improvised action 14 became a template for both the ongoing use of proxies, but also for value of improvising when others had more power (Alinsky, 2010). Many social movements also highlight early improvised actions as touchstones for movement identity, such as Rosa Park’s keeping a seat on the front of the bus. Improvised re-interpretation as a tool for control. Macro improvisation for strategic domination also occurs when the improviser uses on-the-spot reinterpretation of existing meanings as a weapon to gain control. Preston (1991), for example, describes how a manager re-interpreted the firm’s industry classification to be one where strikes could not occur, in order to control a pending strike. Interactions between levels of improvisation and other processes The dichotomy of micro versus macro processes oversimplifies the multiple nested subsystems and activities within organizations (Kozlowski & Klein, 2000). Nonetheless, research shows that interactions of improvisational processes can shape long term organizing patterns. Interactions can involve traditional, explicit feedback loops. In more nuanced process-oriented frameworks, improvisation can generate nuanced “successive layerings of backtalk” (Yanow & Tsoukas, 2009, p. 1348) between organizational participants, material contexts, and processes. In many cases, a deliberate improvisational process for temporary purposes leads to unintended, more enduring change at other levels (Smets, 2014; Baker et al., 2003). In one exemplary study, Smets et al. (2014) describe improvisational activity by lawyers in a firm combining British and German legal expertise. The lawyers repeatedly devise modifications of old action templates in an ad hoc way, often in pursuit of “getting things done.” Smets and colleagues provide convincing evidence that such 15 micro-improvisations have lasting influence on firm-level interpretive systems, and even on field-level norms and practices. Much of the transmission occurs through dayto-day interaction of actors during practice. The study offers an important illustration of low-visibility, high-impact transformation processes. In an extensive study of more visible transformation processes during responses to 9/11, Wachtendorf (2004) describes additional interactions of improvisational forms and other processes. Some improvisational activity involved recreation of an existing prior command center, and replicated the functions of that center (reproductive improvisation). Other improvisational activity interacted with prior templates, major political struggle and deliberate planning to create whole new systems to move and sort all debris, including human remains (creative improvisation). This study provides evidence of both gradual and of dramatic transformations that involve improvisational processes. Finally, a study of entrepreneurial firms by Baker, Miner and Eesley (2003) describes multi-level interactions and impact. Some entrepreneurs design a firm as they execute its founding steps, improvising the entire strategic action of starting a firm. Early improvisational activity also sometimes shapes core organizational identity and values. For example, the founder improvised a positive answer to a valued interviewee who wanted to work at a family-oriented company. A desire for consistency led the founder to actually enact significant formal family-centered policies and identity. Originally improvisational activities morphed into inscribed routines and sources of identity that significantly molded organizations. 16 These studies underscore several important multi-level interactions related to the improvisation process, each worthy of investigation as a distinct overall process important to organizing. First, actors sometimes improvise an action pattern as a ‘patch’ to resolving a problem, but later discard or replace it with a pre-designed pattern (Miner et al., 2001). These may be dropped after execution, but may also sometimes provide unexpected insights available to inform disconnected later actions (Antonacopolous, 2009). In a different sequence of activities, the original proto-routine becomes a legitimate, formally constituted organizational routine within the taken for granted templates for action. Broad communities can gain experience via repetition of an initially improvised practice, and transform their improvisations into distinctive organizational practices (Plowman et al., 2007). A focal practice may be retained through many other processes including power interactions, interpretive interactions, simple momentum, and relatively invisible influences during practice (McGinn & Keros, 2002; Smets, et al., 2014). In another and conceptually distinct sequence, participants first assess the outcome of an initial improvisational process. If they see it as valuable, they repeat its content. Improvisation here serves as step in trial and error learning processes that can affect long-term organizational memory, routines, practices and values (Miner et al., 2001). Different performance feedback frameworks for assessing ‘success’ of a microimprovisation will lead to different higher-level outcomes. Recent evidence suggests that forgetting may also make ongoing improvisation more effective (Akgun et al. 2007), consistent with selective retention. 17 All of these interaction patterns then, can shape long term changes in organizing in specific domains such as operations, production, human resources, product development, financial management, external relations, or partnership formation. Long-term change will depend on which of the retention processes, such as power or performance feedback, dominate or interact with each other. These processes to institutionalize a focal improvised action design differ, we suggest, from the processes that shape the tendency to improvise in the future. Developing a tendency to improvise represents a distinct process pathway. This has obvious implications for organizational transformation (Gong et al., 2005; Winter, 1983). Crossan and Sorrenti (1997) have suggested many organizational contexts that may promote improvisation, pointing to factors to consider in studying potential processes by which it develops. Schon’s (1983) work raises interesting questions of whether skillful improvisational activities have distinct development paths compared to unskilled improvisational activities. The extant work, then describes important ways that interactions of improvisational processes shape organizing patterns. Nonetheless, gaps remain that suggest promising frontiers for future work, which we discuss below. Gaps and frontiers in the study of the process of improvisation The analysis above reveals issues both across and within the modes of improvisation where further exploration offers special promise. Gaps and frontiers across modes of improvisation Four important gaps and frontiers cut across the modes identified above, three theoretical and one methodological. They include: further development of the role of 18 interpretation, the role of non-utilitarian motivations, the role of emotion, and methodological challenges in detecting improvisation processes. Interpretive processes and improvisation. Karl Weick (1993) played a leading role in legitimizing organizational improvisation for scholarly research. His iconic explication of the Mann Gulch disaster highlighted nuances of disruptions of interpretive systems and their link to improvisation processes. In other work he describes many nuanced subprocesses, such as how re-interpretation can play a decisive role: by repeating a note played in error, for example, the improviser can transform a mistake into a meaningful musical phrase (Weick, 1998). Interpretive improvisation can appear in all forms of improvisation. Further development of its role deserves major attention. What is the role of imagination in improvisation? How does improvisational practice interweave with interpretation? Does an improvised re-interpretation unfold differently from a planned reinterpretation? How do problems become re-interpreted as opportunities and the other way round? Motivations for improvisation. Current theory sometimes notes the existence of both problem and opportunity driven improvisations, but studies typically fail to trace them separately. Do they involve different microprocesses? Field reports describe how actors sometimes improvise because they enjoy improvising for its own sake. Does this motivation spur different processes than utilitarian improvisation or have different long term influence? Emotion and improvisation. Improvised performances are by definition irreversible: the pattern already performed cannot be undone. This suggests that improvising can generate fear, or relief from boredom, as well as feelings of 19 transcendence (Hatch 1997; Berliner, 1994; Hmieleski et al., 2013). Do emotional factors influence all forms of improvisation? Does emotion play a distinct role in links between micro and macro processes, and the interpretation of improvisation itself? Insights into these issues can not only advance process understanding of improvisation but of how of organizational actors embody their practices more broadly (Antonacopoulou, 2008; Yanow &Tsoukas, 2009). Detecting improvisation processes. Researching improvisation presents challenges in part because one cannot deduce from the content of a particular performance how much in what way it involved improvisational processes. Time periods used to bracket the flow of action can affect whether a focal set of activities seems to involve design during execution or instead embody very fastmoving set of cycles of planning then execution (Van de Ven et al., 1999). Choices about the degree of novelty used to indicate improvisational processes will also shape the observed relative presence of improvisation. It will help if investigators clarify their choices on how large a deviation from prior templates (novelty) they require to assess an activity as improvisational, and how they approach assessing convergence of design and execution of a performance. Gaps within each of the four modes of improvisation Micro improvisation as ad hoc actions to accomplish work. Although much improvisation research has focused on this form, important questions remain. There is still relatively little detailed examination of how differences in the degree of novelty generated during improvisation influence later processes (Vera & Crossan, 2005). How do we account for the fact that effective organizational actors skillfully navigate 20 baseline improvisation in work practices, but other forms of improvisation can create major coordination problems in the eyes of many organizational actors? How can improvisations with positive ampliative potential be identified? What specific characteristics of improvised processes are perceived as relevant enough to be inscribed in the organization’s memory? Conceptualizing memory as a process can offer new perspectives on the unfolding of organizational improvisation. Macro improvisation as strategy. Eisenhardt and her colleagues’ studies often focused on the fast moving computer industry, but recent work indicates that principles such as minimal structuring can also be useful in mature industries, such as retailing (Sonenhein, 2014). Longitudinal and comparative research on start-ups and entire sectors (Ocasio & Joseph, 2008) can advance understanding of how traditional forms of strategy (planning) coexist with improvisation. How does improvisation relate to strategic surprises (Lampel & Shapira, 2001) and sudden organizational collapse? What safeguards reduce the potential dangers of improvisation that risks an organizations’ entire resources or identity? What practices reduce the chances of improvisational drifting? How do contingency planning, experimentation and improvisation play distinct roles (Binns et al., 2014; Chia & Holt, 2009, Chia, 2014)? Under what conditions do effective improvisational capabilities thrive versus drifting into “improvisational momentum” (Gong et al., 2006)? How can effective organizational improvisation be learned (Vera & Crossan, 2005; Hmieleski, Corbett & Baron, 2013)? Micro improvisation as political ingenuity in the organizational underlife. The investigation of how power influences practitioner’s ability to recognize and pursue non-sanctioned opportunities to acquire resources and to act “undercover” 21 (Mainemelis, 2010) will be immensely helpful for probing improvisation’s link to organizing (Kamoche et al., 2003; Yanow and Tsoukas 2009). The potential for hidden improvisation also highlights the possibility of reverse pattern in which organizational actors hide planning or routines under the guise of improvisation. March’s and his colleagues’ studies of garbage can processes (1986), for example, describe this relatively underexplored process. Macro improvisation as strategic domination. Re-examination of undertheorized descriptions of improvisation processes in warfare or in social movements offers a promising window for theory development. For example, how do guerilla warfare units achieve transitions to enduring organizations that can operate as equals in a world of enduring, formalized organizations? How do emotional and interpretive activities play a role in improvisation in explicit battles over identity and strategic missions? Gaps in research on interactions between improvisational levels, forms and other processes. Finally, while extant theory reveals rich interactions across levels and of improvisation, important frontiers remain. Promising lines of work include but are not limited to deepening understanding of improvisation’s links to distinct institutionalization processes, organizational performance, and multi-level outcomes -including cultures or institutional fields, as sketched below. First, more detailed observational data will improve understanding of how actors recreate improvised content. Further work can usefully probe non-professional settings or improvisation but non-engaged actors, in contrast to much work on engaged professionals. When does a sequence of micro actions to accomplish work or underlife improvisations become part of a foundational change process? How do 22 evaluation, power and interpretive processes influence each other and change over time? More fundamentally, what if we start with the assumption that improvisational activities come before all others, and then theorize about how they eventually generate knots of regularity in action that we call routines or plans (Tsoukas, 2010)? Second, exactly when and how does an initial improvisational episode or sequence of actions affect later tendencies to improvise at all? What about capabilities to improvise effectively versus ineffectively? Is this a matter of practising (Antonacopoulou, 2008) and if so, how, precisely, does it unfold? How does this process affect a transactive memory system (Vera & Crossan, 2005; Winter, 2003)? How and when do organizations develop an “addiction” to improvisational processes? Is it possible that current improvisational tendencies are actually remnants of improvisational processes during organizational formation that are not yet touched by bureaucracy or routines? Improvisation and performance. Interactions between levels of improvisation and other processes can impact outcomes at all levels. How do amplification processes of improvisation create different trajectories for different types of strategic performance – both short and long term? Does the long-term impact of an improvisational process differ from the performance impact of a planned innovation or a random deviation? What is theoretically new in such models compared to the existing literature on unintended outcomes of local deviations in practice? Multi level outcomes. Much multi-level work that explicitly flags improvisation tackles interactions between the individual/team and the organizational level (see Smets, above for an exception). This invites further exploration of interactions affecting entire institutional fields and on the role of culture. Nollywood, the Nigerian 23 film industry, offers a case in point. Uzo and Mair’s (2014, p.65) qualitative study describes actors in this industry as habile improvisers and attributes this to the sector’s low level of professionalism and to the high the value of rapid adaptation. The authors show how a sound technician without preparation can replace an unexpectedly absent actor on the spot and how “stories and scripts were spontaneously and collectively improvised as the movie production process unfolded.” The study suggests a pervasive, cultural comfort with conceiving action as it unfolds. Studies in contexts as geographically diverse as India (Capelli et al., 2010) and Southern Europe (Aram & Walochik, 1997; Cunha, 2005) show that improvisational skills can be enacted up to a point that they become institutionalized as normal features of managerial practice. Here, too, it will be interesting to probe whether this has developed over time, or whether initial improvisational tendencies simply have not been over-ridden by planning and routinization norms. Summary: Advancing process theory through research on improvisational processes By exploring the frontiers outlined above, research can advance process theory broadly and deepen understanding of the improvisation process itself. By definition, the improvisation process involves dynamics and practice -- hallmarks of process theory (Feldman & Orlikowksi, 2011; Langley et al., 2013) and process researchers have already played a key role developing improvisation theory. Extant research implies, however, that the improvisation construct is not a single “secret sauce” that solves all issues of emergent organizational processes, making it vital to develop it further and explore links to other processes. 24 Instead of seeing improvisation as an either-or process, empirical research convincingly portrays varieties and degrees of improvisation that offer theoretical promise. Studies underscore that while improvisation may mark most or all activity in some ways, not all activity is equally improvisational -- and that this is likely to matter. The degree of improvisation in a discrete action can vary in terms of novelty and in the degree to which the design and execution of action converge in time (Crossan, 1998; Cunha et al., 1999; Miner et al., 2001; Weick, 1998). The relative presence of improvisation can vary over time within a stream of action. These nuances offer windows to advance theory. One crucial step will be to conduct even finer-grained research on subprocesses within improvisational incidents or flows of action. Weick (1998) and others have insightfully probed this issue, but to some degree we still have theory based heavily on expert improvisers or engaged professionals. This leaves unresolved how improvisation by non-expert or disengaged actors unfolds. At higher levels of analysis, many studies document intriguing interactions across levels and types of improvisation, but we need more studies that trace the distinct roles of different improvisational forms on both short and long term patterns. Exploring improvisation’s frontiers can also contribute to theories of practice. Feldman and Orlikowski (2011) flag three foundations for practice theory: empirical, theoretical and ontological. This review has emphasized observational empirical studies of improvisation in action. Improvisation by definition involves performance, but its link to practice theory is still emerging in important ways. Antonacopoulo (2008, 2009), for example, has emphasized the process of practising, which relates to how specific practices can change when they are 25 performed (are in practise). Practising is thus also a practice itself: it entails deliberate, habitual and spontaneous repetition – including rehearsing, reviewing, refining, and changing different aspects of a practice and their relationships. Practising involves imagination and pragmatism that help create space for different courses of future action, key potential aspects of improvisation. Practising is also argued to play an important role in a distinct process of learning in crisis (Antonacopoulou & Sheaffer, 2014). Teasing out improvisation’s links to these related processes represents an important frontier. Conclusion Management theory long saw improvisation as a rare activity that usually leads to bad outcomes. Other work has seen it as a ubiquitous activity that usually leads to good things. The body of research described above paints a richer, more powerful picture. It reveals improvisational processes as varied but also as understandable and impactful. It shows that they interact with each other and other processes to sustain organizing at all levels. Overall, it points to improvisational processes as vital to the ongoing development of process-oriented research. 26 References Akgun, A.E., Byrne, J.C., Lynn, G.S. & Keskin H (2007). New product development in turbulent environments: Impact of improvisation and unlearning on new product performance. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 24: 203-230. Alinsky, S. (2010). Rules for radicals. New York: Random House. Antonacopoulou, E.P. (2008) On the Practise of Practice: In-tensions and ex-tensions in the ongoing reconfiguration of practice. In D. Barry and H. Hansen (eds) Handbook of New Approaches to Organization Studies (pp.112-131). London: Sage. Antonacopoulou, E.P. (2009) Strategizing as practising: Strategic learning as a source of connection. In L.A. Costanzo, L.A. and R.B. McKay (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Strategy and Foresight (pp.169-181). London: Sage. Antonacopoulou, E.P. and Sheaffer, Z. (2014) Learning in Crisis: Rethinking the Relationship between Organizational Learning and Crisis Management. Journal of Management Inquiry, 23(1): 5-21. Aram, J.D. & Walochik, K. (1996). Improvisation and the Spanish manager. International Studies of Management and Organization 26: 73-89. Baker T., Miner A.S. & Eesley D.T. (2003) Improvising firms: Bricolage, account giving and improvisational competencies in the founding process. Research Policy 32: 255-276. Baker, T., & Nelson, R. (2005). Creating something out of nothing: Resource construction through entrepreneurial bricolage. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50, 329-366. Balogun, J. & Johnson, G. (2004). Organizational restructuring and middle manager sensemaking. Academy of Management Journal, 47(4), 523-549. Bechky, B & Okhuysen, G. (2011). Expected the unexpected? How SWAT officers and film crews handle surprises. Academy of Management Journal, 54(2): 239-261. Bergh, D.D. & Lim, E.N.K. (2008). Learning how to restructure: Absorptive capacity and improvisational views of restructuring actions and performance. Strategic Management Journal, 29, 593-616. 27 Berliner, P. F. (2009). Thinking in jazz: The infinite art of improvisation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Bigley, G & Roberts, K. (2001). The incident command system: High-reliability organizing for complex and volatile task environments. Academy of Management Journal, 44(6):1281-1299. Bingham, C.B. (2009). Oscillating improvisation: How entrepreneurial firms create success in foreign market entries over time. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 3: 321-345. Bingham, C.B. & Davis J.P. (2012). Learning sequences: Their existence, effect and evolution. Academy of Management Journal, 55(3), 611-641. Bingham, C. & Eisenhardt K.M. (2011). Rational heuristics: The ‘simple rules’ that strategists learn from process experience. Strategic Management Journal 32: 1437-1464. Brown, S.L. & Eisenhardt, K.M. (1997). The art of continuous change: Linking complexity theory and time-paced evolution in relentlessly shifting organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly 42: 1-34. Capelli, P., Singh, H., Singh, J. & Useem, M. (2010). The India way. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. Charles, K. & Dawson, P. (2011). Dispersed change agency and the improvisation of strategies during processes of change. Journal of Change Management, 11(3), 329-351. Chia, R. (2014). In praise of silent transformation – Allowing change through ‘letting happen’. Journal of Change Management, 14(1):8-27. Chia, R. & Holt, R. (2009). Strategy without design: The silent efficacy of indirect action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Ciborra, C. (1999). Notes on improvisation and time in organizations. Accounting, Management and Information Technologies, 9, 77-94. Clegg, S.R., Cunha, J.V. & Cunha, M.P. (2002). Management paradoxes: A relational view. Human Relations, 55(5), 483-503. Crossan, M. (1998). Improvisation in action. Organization Science, 9(5):593-599. Crossan, M. M., & Sorrenti, M. (1997). Making sense of improvisation. Advances in Strategic Management, 14, 155-180. 28 Crozier, M. & Friedberg, E. (1976). L’acteur et le système. Paris: Seuil. Cunha, M.P. (2005). Adopting or adapting? The tension between local and international mindsets in Portuguese management. Journal of World Business, 40(2), 188-202. Cunha, M.P., Clegg, S.R. & Kamoche, K. (2006). Surprises in management and organization: Concept, sources, and a typology. British Journal of Management, 17, 317-329. Cunha, M.P., Cunha, J.V. & Kamoche, K. (1999). Organizational improvisation: What, when, how and why. International Journal of Management Reviews, 1(3), 299341. Cunha, M.P., Kamoche, K. & Cunha, R.C. (2003). Organizational improvisation and leadership: A field study in two computer-mediated settings. International Studies of Management & Organization, 33(1), 34-57. Cunha, M.P., Neves, P., Clegg, S. & Rego, A. (forthcoming). Tales of the unexpected: Discussing improvisational learning. Management Learning. Cyert, R.M. & March, J.G. (1963). A behavioral theory of the firm. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell. Dailey, S.L. & Browing, L. (2014). Retelling stories in organizations: Understanding the functions of narrative repetition. Academy of Management Review, 39(1), 22-43. De Certeau, M. (1984). The practice of everyday life. Berkeley: University of California Press. Edmondson, A. C. & Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1, 23-43. Eisenhardt, K.M. & Tabrizi, B. (1995). Accelerating adaptive processes: Product innovation in the global computer industry. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40, 84-110. Farjoun, M. (2010). Beyond dualism: Stability and change as duality. Academy of Management Review, 35, 202-225. Feldman, M. & Pentland, B. (2003). Reconceptualizing organizational routines as a source of flexibility and change. Administrative Science Quarterly, 48(1): 94118. 29 Feldman, M.S. & Orlikowski, W.J. (2011). Theorizing practice and practicing theory. Organization Science, 22: 1240-1253. Garud R, Jain S and Tuertscher P (2008) Incomplete by design and designing for incompleteness. Organization Studies 29: 351-371. Gong, Y., Baker, T. & Miner, A.S. (2005). The dynamics of routines and capabilities in new firms. Unpublished manuscript. Gong, Y., Baker, T. & Miner, A.S. (2006). Failures of entrepreneurial learning in knowledge-based startups. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, 15, part 2. Grant, A.M. & Ashford, S.J. (2008). The dynamics of proactivity at work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 28, 3-34. Grant, R.M. (2008). Strategic planning in a turbulent environment: evidence from the oil majors. Strategic Management Journal, 24(6), 491-517. Guevara, Che (2002). Guerrilla warfare. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. Hargadon, A.B. & Douglas, Y. (2001). When innovations meet institutions: Edison and the design of the electric light. Administrative Science Quarterly 46: 476-501. Hatch, M. J. (1997). Commentary: Jazzing up the theory of organizational improvisation. Advances in Strategic Management 14: 181-192. Hmieleski, K.M., Corbett, A.C. & Baron, R.A. (2013). Entrepreneurs’ improvisational behavior and form performance: A study of dispositional and environmental moderators. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 7, 138-150. Jarzabkowski, P. & Kaplan, S. (2014). Strategy tools in-use: A framework for understanding technologies of rationality in practice. Strategic Management Journal, forthcoming. Kamoche, K. & Cunha, M.P. (2001). Minimal structures: From jazz improvisation to product innovation. Organization Studies, 22, 733-764. Kamoche, K., Cunha, M.P. & Cunha, J.V. (2003). Towards a theory of organizational improvisation: Looking beyond the jazz metaphor. Journal of Management Studies, 40(8), 2023-2051. Kendra, J., & Wachtendorf, T. (2003). Elements of resilience after the World Trade Center disaster: Reconstituting New York City’s Operations Center. Disasters, 27(1): 37-53. King, A. W., & Ranft, A. L. (2001). Capturing knowledge and knowing through improvisation: What managers can learn from the thoracic surgery board 30 certification process. Journal of Management, 27(3), 255-277. Kozlowski, S.W.J. & Klein, K.J. (2000). A multilevel approach to theory and research in organizations: Contextual, temporal, and emergent processes. In K.J. Klein & S.W.J. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations: Foundation, extensions, and new directions (pp.3-90). San Francisco: Jossey Bass. Kyriakopoulos, K. (2011) Improvisation in product innovation: The contingent role of market information sources and memory types. Organization Studies 32: 10511078. Lampel, J. & Shapira, Z. (2001). Judgmental errors, interactive norms and the difficulty of detecting strategic surprises. Organization Science, 12, 599-611. Langley, A., Smallman, C., Tsoukas, H. & Van de Ven, A.H. (2013) Process studies of change in organizations and management: Unveiling temporality, activity and flow. Academy of Management Journal, 56(1), 1-13. Magni, M., Proserpio, L., Hoegl, M. & Provera, B. (2009). The role of team behavioral integration and cohesion in shaping individual improvisation. Research Policy, 38, 1044-1053. Mainemelis, C. (2010). Stealing fire: Creative deviance in the evolution of new ideas. Academy of Management Review 35: 558-578. Manning, P.K. (2008). Goffman on organizations. Organization Studies 29(5), 677-699. McGinn, K., & Keros, A. 2002. Improvisation and the logic of exchange in socially embedded transactions. Administrative Science Quarterly, 47(3):42-473. Mantere, S. & Vaara, E. (2008). On the problem of participating in strategy: A critical discursive perspective. Organization Science, 19(2), 341-358. March, J.G. (1981). Footnotes to organizational change. Administrative Science Quarterly, 26, 563-577. March JG (1976) The technology of foolishness. In JG March and J. Olsen (Eds.), March, J.G. &Olsen, J.P. (1986). Garbage can models of decision making in organizations. . in J.G. March & R. Weissinger-Baylon (Eds.), Ambiguity and command: Organizational perspectives on military decision making (pp.11-35). Reading, MA: Miller, P. & Wedell-Wedellsborg, T. (2013). The case for stealth innovation. Harvard Business Review, March, 91-97. Miner, A., Bassoff, P. & Moorman, C. (2001). Organizational improvisation and 31 learning: A field study. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46(2):304-337. Mintzberg, H. (1994). Rise and fall of strategic planning. New York: Simon and Schuster. Moorman, C. & Miner, A. (1998a). The convergence between planning and execution: Improvisation in new product development. Journal of Marketing, 62, 1-20. Moorman, C., & Miner, A. (1998b). Organizational improvisation and organizational memory. Academy of Management Review, 23(4), 698-723. Ocasio, W.A. & Joseph, J. (2008). Rise and fall – or transformation? The evolution of strategic planning at the General Electric Company, 1940-2006. Long Range Planning, 41, 248-272. Orlikowski, W.J. (1996). Improvising organizational transformation over time: A situated change perspective. Information Systems Research, 7, 63-92. Orr, J. (1990). Sharing knowledge, celebrating identity: War stories and community memory in service culture. In D.S. Middleton & D. Edwards (Eds.), Collective remembering: Memory in society. Newbury Park: Sage. Plowman, D.A., Baker, L.T., Beck, T., Kulkarni, M., Solansky, S. & Travis, D. (2007). Radical change accidentally: The emergence and amplification of small change. Academy of Management Journal, 50, pp. 515-543. Preston, A. (1991). Improvising order. Organization analysis and development 8. Schon, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner. New York: Basic Books. Smets, M., Morris, T. & Greenwood. R. (2012). From practice to field: A multilevel model of practice-driven institutional change. Academy of Management Journal, 55(4), 877-904. Sonenshein, S. (2014). How organizations foster the creative use of resources. Academy of Management Journal, 57(3):814-848. Ton, Z. (2014). Good jobs strategy: How the smartest companies invest employees to lower costs and boost profits. Seattle: Lake Union. Tsoukas, H. (2010). Representation, signification, improvisation – A three-dimensional view of organizational knowledge. In H. Canary & R. D. McPhee (Eds.), Communication and organizational knowledge. New York: Routledge: New York. Tsoukas H. & Chia R. (2002). On organizational becoming: Rethinking organizational change. Organization Science, 13, 567-582. 32 Uzo, U. & Mair, J. (2014). Source and patterns of organizational defiance of formal institutions: Insights from Nollywood, the Nigerian movie industry. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 8, 56-74. Van de Ven, A., Polley, D., Garud, R., Venkataraman, S. (1999). The innovation journey. New York: Oxford University Press. Vera, D. & Crossan, M. (2005). Improvisation and innovative learning in teams. Organization Science, 16(3), 203-224. Vera, D., Nemanich, L., Vélez-Cástrillon, S. & Werner, S. (2014). Knowledge-based and contextual factors associated with R&D teams’ improvisation capability. Journal of Management,forthcoming. Wachtendorf, T. (2004). Improvising 9/11: organizational improvisation following the World Trade Center disaster. Dissertation, University of Delaware. Weick, K.E. (1993). The collapse of sensemaking in organizations: The Mann Gulch disaster. Administrative Science Quarterly, 38, 628-652. Weick, K.E. (1998). Improvisation as a mindset for organizational analysis. Organization Science, 9, 543-555. Winter, S.G. (2003). Understanding dynamic capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 24, 991-995. Yanow, D. & Tsoukas, H. (2009). What is reflection-in-action? A phenomenological account? Journal of Management Studies, 46(8), 1339-1364. 33