Russia's Transition Crisis

advertisement

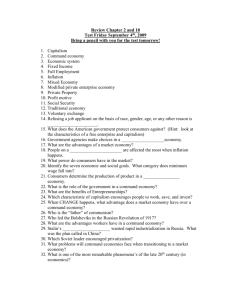

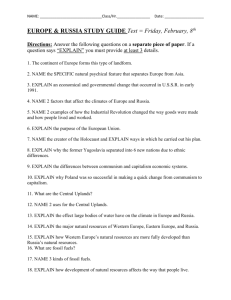

Russia’s Transition Crisis Yeltsin with Clinton at Camp David: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vHfbp L0NDmw Aug. 1991: the August Coup Dec. 1991: Belovezhye Agreement abolishes USSR Jan. 1992: Shock Therapy begins Sept.-Oct. 1993: Yeltsin’s coup Dec. 1993: Duma election and referendum of the new constitution 1994-96: the first war in Chechnya Mar. 1996: Yeltsin re-elected as President Aug. 1998: Russia defaults on its loans Aug. 1999: Putin appointed Prime Minister, start of the second war in Chechnya, Yeltsin resigns, Putin becomes Acting President Mar. 2000: Putin is elected President 1991-93 Open clash between pro-capitalist and pro-Soviet elites Pro-Soviets lose because they resort to a coup Democratic resistance empowers pro-capitalists USSR is dissolved by pro-capitalist elites to remove obstacles to capitalist transition Transition to capitalism is effected The cost and pain of transition generates opposition Democracy becomes an obstacle to transition Yeltsin turns to authoritarianism How transition to capitalism affects society: Accumulation of capital Unemployment and poverty Dismantling of the welfare state Zero-sum struggles for survival Political options for post-communist countries: 1. --Liberal democracy (elections, rule of law, accountable government) --Reform authoritarianism --Reliance on external forces (Western loans and investments, joining NATO, EU) --Alternative reform strategies based on democratic principles If society accepts capitalism as a normal way of life, such a society is better prepared to cope with the transition crisis If society is not familiar with capitalism, it tends to reject the changes In the first case, democracy aids in the transition In the second case, it may prevent it Which factors account for success in transition from state socialism to capitalism? 1. ACCEPTANCE OF CAPITALISM AS A NORMAL SYSTEM Historical experience with capitalism Poland, Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovenia – elements of capitalism in the economy were present to a higher degree Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Romania, Bulgaria, Central Asian countries – market institutions were almost non-existent So, it was a case of restoration of capitalism, rather than a re-invention of capitalism 2. SOCIETY’S POTENTIAL TO INFLUENCE THE COURSE OF TRANSITION The strength of civil society The stronger the civil society, the more the reform strategies have to take into account citizen reactions to the transition As a result, the transition process is relatively less costly Since the transition costs fall most heavily on the majority of society, the ability of citizens to defend their interests presents challenges to the transition 3. ETHNOPOLITICS Multiethnic societies Patterns of and results of transition vary between different ethnic groups Competition easily acquires ethnic connotations Ethnopolitical mobilization leads to conflict Monoethnic societies Similarity of patterns Competition not ethnically coloured Ethnopolitical mobilization may shore up stability Success is most likely: In a country with: embedded market institutions, a strong civil society, not significantly divided along cultural-ethnic lines Failure is most likely: In a country with: embryonic market institutions, weak civil society, ethnically divided Most post-communist countries are somewhere between these two extremes ‘‘What emerged after the defeat of communism was the ethos of competition, the ethos of getting wealthy… Economic evolution pushed our countries toward… heartless market economy… a rat race, and money became the only measure of the value… of life’s success’’ Adam Michnik, leader of Poland’s Solidarity movement, 1999 Russia’s Great Depression 1991-96: GDP - fell by 45% Industrial output – fell by 49% Agricultural output – fell by 32% 1991-1999: Textile, leather and fur, and footwear industries: Output fell by nearly 10 times, Garment industry - by 5 times, Meat and dairy industries - by 3 times. The share of high-tech products in GDP fell from 45.3 to 25 percent of the GDP. In 2000, labour productivity in Russia was 5 times lower than in the United States --------------------------------------- Dying for Growth: Global Inequality and the Health of the Poor: Jim Yong Kim, Joyce V. Millen, Alec Irwin and John Gershman (Eds.), Common Courage Press, Monroe, 2000 Facts and Figures: Raw Materials Exporter. - Ekonomika i zhizn, No. 43, 2000 The social impact: A double blow to the livelihoods of most Russians: a decline in their incomes and savings a drastic reduction of social services for which they depended on the state. In 1999, the incomes of over 40% of the population (60 million people) were below the official subsistence level of 1,138 roubles a month, which was the equivalent of about US$40.[i] The official (government-determined) minimum wage in 2000 was 132 roubles (US$ 4,74) a month.[ii] The average monthly salary was 2,403 roubles (US$86).[iii] About half of all families with one child lived below the subsistence level. In 75% of families with three children, each family member had less than a dollar a day to live on.[iv] [i] Izvestia, 4.07.2000. [ii] Moscow Times, 18.10.2000 [iii] AFP, 31.10.2000 [iv] Moscow Times, 18.10.2000 [v] VCIOM, Press-vypusk 3.03. 2000 Countries compared by per capita income: http://www.indexmundi.com/g/r.aspx?v=67 Social inequality In the last years of the Soviet Union, the gap between the rich and poor was estimated to be 4:1. It is usually assumed that if the gap grows beyond 10:1, society becomes unstable. In 1999, the gap in Russia was 15:1, according to official statistics. According to the estimates of the Institute of Socioeconomic Problems of the Population of the Russian Academy of Sciences, the actual gap was much wider: Total income of the 10% richest households was 44 times higher than that of the poorest 10%.[ii] [i] Izvestia, 4.07.2000 [ii] Moscow Times, 18.10.2000. The world’s billionaires, 2011, Forbes Magazine: http://www.forbes.com/billionaires/list/ Total – 1,210 US – 412 Russia – 101 China – 95 India – 55 Germany – 52 Brazil – 40 Turkey – 38 Hong Kong – 36 UK – 33 The Wealth Report, 2012: http://www.thewealthreport.net/The-Wealth-Report2012.pdf Making them immortal: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-2175374/Russianresearch-project-offers-immortality-billionaires--transplanting-brainsrobot-bodies.html Former Russian billionaire No.1 – Mikhail Khodorkovsky Khodorkovsky’ letter from jail, 2004: “Russian liberalism has suffered a defeat because it ignored two things: first, some key elements of Russia’s historical experience, second, vital interests of the overwhelming majority of the Russian people. And it was mortally afraid of telling the truth. I do not want to say that Russia’s liberal leaders set it as their goal to deceive the people. Many of the liberals who came to power with Yeltsin were convinced that liberalism offered the only right solution for Russia, and that a “liberal revolution” was needed in this exhausted country which had historically tasted so little freedom. But they understood this revolution in a very peculiar, elitist way. They cared about the conditions of life and work of those 10% of Russians who were ready to embrace decisive social change and to abandon government paternalism. But they forgot about the 90%. And they covered up their failures with lies. …They deceived most Russians about privatization. They gave everyone a privatization voucher, promising that at some point, one would be able to buy two cars with it. Well, if you were an enterprising financial dealer with access to insider information and the brains to analyze it, you would probably be able to buy ten cars with your voucher. But the promise was given to everyone. They closed their eyes to the social realities of Russia, as they carried out privatization. Ignoring the social costs of it, they called it painless, honest and fair. But we do know what the people think of this privatization. …No fundamental reformation of society is possible without social stability and social peace. But the Russian liberals chose to disregard it and created a chasm between themselves and the people. And they used the informationbureaucratic pump of PR technologies to fill the chasm with liberal myths…” “Vedomosti”, March 29, 2004 Death of a Nation http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J1OyI Jtjdpo Consequences for democratic development… Who needs democracy – and for what ends? The Russian experiment with democracy, started in 1985, was driven by elite perceptions of the efficiency of democratic political systems compared to authoritarian systems It was expected to save and revive the Soviet system When democratic practices began to threaten the Soviet system, there was an attempt to suspend it – The August 1991 coup After the attempt failed, democracy was used as the most effective way of destroying that system Democracy was a potent weapon against communist rule and the Soviet state Democracy did help accomplish the demolition mission What about the mission of construction? How useful has democracy been as a tool to build a capitalist political economy? It did help accomplish: The shift to market economy and private ownership Partial legitimization of capitalism Partial integration with the West Accomplishing even those tasks did considerable damage to democratic governance Consolidation of capitalism? A capitalist political economy capable of reproducing and sustaining itself in the context of globalization Productivity and competitiveness A functional state Improvement of socioeconomic conditions Social and political stability How does political democracy relate to these tasks? In general, democratic capitalism works better than authoritarian capitalism In the long run: A normative liberal democracy would probably suit Russia best But what about the short run? In the short run, there is a deep and acute conflict between the requirements of democratic development and the tasks of capitalist consolidation Democracy became an obstacle to consolidation of capitalism, a mortal threat to the preservation of Russia’s post-communist regime The only way that regime could survive the social upheaval of the 1990s was through subverting and limiting democratic practices in Russia