Harlem Renaissance Powerpoint

THE HARLEM

RENAISSANCE

A NEW AMERICAN VOICE

• While the Modernism movement was happening in New

York’s Greenwich

Village and in Paris,

African American writers and artists were finding their own style in northern Manhattan, in Harlem.

GOING MAINSTREAM

• The Harlem Renaissance was publicly recognized in March 1924, when young African

American writers met the literary editors of the city.

• The Harlem phenomenon continued throughout the 1920’s and into the 1930’s.

• Though the writers of the Harlem Renaissance belonged to no single school of literature, but they did form a coherent group.

• They saw themselves as part of a new and exciting movement.

• Their works opened the door for the African

American writers who would follow.

HARLEM RENAISSANCE VIDEO

BEGINNINGS

• The Harlem

Renaissance began in

1921, when Countee

Cullen’s poem, “I Have a

Rendezvous With Life

(with apologies to Alan

Seeger),” was published.

• The poem was a response to Seeger’s

“I Have a Rendezvous

With Death.”

I Have a Rendezvous With Life

I have a rendezvous with Life,

In days I hope will come,

Ere youth has sped, and strength of mind,

Ere voices sweet grow dumb.

I have a rendezvous with Life,

When Spring's first heralds hum.

Sure some would cry it's better far

To crown their days with sleep

Than face the road, the wind and rain,

To heed the calling deep.

Though wet nor blow nor space I fear,

Yet fear I deeply, too,

Lest Death should meet and claim me ere

I keep Life's rendezvous.

Countee Cullen (1903-1946)

"I Have a Rendezvous with Death"

I HAVE a rendezvous with Death

At some disputed barricade,

When Spring comes back with rustling shade

And apple-blossoms fill the air —

I have a rendezvous with Death 5

When Spring brings back blue days and fair.

It may be he shall take my hand

And lead me into his dark land

And close my eyes and quench my breath —

It may be I shall pass him still.

10

I have a rendezvous with Death

On some scarred slope of battered hill,

When Spring comes round again this year

And the first meadow-flowers appear.

God knows 'twere better to be deep 15

Pillowed in silk and scented down,

Where love throbs out in blissful sleep,

Pulse nigh to pulse, and breath to breath,

Where hushed awakenings are dear...

But I've a rendezvous with Death 20

At midnight in some flaming town,

When Spring trips north again this year,

And I to my pledged word am true,

I shall not fail that rendezvous.

ZORA NEALE HURSTON

• Born on Jan. 7, 1891, in

Notasulga, Alabama, Hurston moved with her family to

Eatonville, Florida, when she was still a toddler.

• In Eatonville, Zora was never indoctrinated in inferiority, and she could see the evidence of black achievement all around her. She could look to town hall and see black men, including her father, John

Hurston, formulating the laws that governed Eatonville.

THE CURIOUS CASE OF ZORA

• Zora worked a series of menial jobs over the ensuing years, struggled to finish her schooling, and eventually joined a Gilbert & Sullivan traveling troupe as a maid to the lead singer.

• In 1917, she turned up in Baltimore; by then, she was 26 years old and still hadn't finished high school.

• Needing to present herself as a teenager to qualify for free public schooling, she lopped 10 years off her life--giving her age as 16 and the year of her birth as 1901. From that moment forward, Hurston would always present herself as at least 10 years younger than she actually was.

LET THE WRITING BEGIN!

• By 1935, Hurston--who'd graduated from Barnard College in 1928--had published several short stories and articles, as well as a novel and a well-received collection of black Southern folklore.

• But the late 1930s and early

'40s marked the real zenith of her career. She published her masterwork, Their Eyes Were

Watching God , in 1937;

From THEIR EYES WERE WATCHING GOD

Seeing the woman as she was made them remember the envy they had stored up from other times. So they chewed up the back parts of their minds and swallowed with relish. They made burning statements with questions, and killing tools out of laughs. It was mass cruelty. A mood come alive, Words walking without masters; walking altogether like harmony in a song.

"What she doin coming back here in dem overhalls?

Can't she find no dress to put on? -- Where's dat blue satin dress she left here in? -- Where all dat money her husband took and died and left her? -- What dat ole forty year ole 'oman doin' wid her hair swingin' down her back lak some young gal? Where she left dat young lad of a boy she went off here wid? -- Thought she was going to marry? -- Where he left her? -- What he done wid all her money? -- Betcha he off wid some gal so young she ain't even got no hairs -- why she don't stay in her class?"

UNAPPRECIATED TALENT

• When her autobiography,

Dust Tracks on a Road , was published in 1942,

Hurston finally received the well-earned acclaim that had long eluded her.

• Hurston never received the financial rewards she deserved.

• (The largest royalty she ever earned from any of her books was $943.75.)

HEY MAN, GOT A DOLLA?

• When she died in 1960-

-at age 69, neighbors had to take up a collection for her funeral.

• The collection didn't yield enough to pay for a headstone, however, so Hurston was buried in a grave that remained unmarked until 1973.

A STAR IS BORN

• Six months later,

Langston Hughes’ poem, “The Negro

Speaks of Rivers,” was published.

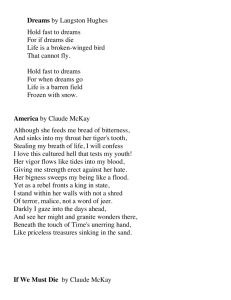

THE NEGRO SPEAKS OF RIVERS by Langston Hughes

I've known rivers:

I've known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young.

I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep.

I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it.

I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln went down to New Orleans, and I've seen its muddy bosom turn all golden in the sunset.

I've known rivers:

Ancient, dusky rivers.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

Hear Langston read

“The Negro Speaks of Rivers.”

LANGSTON HUGHES

• James Langston Hughes was born February 1,

1902, in Joplin, Missouri.

• He was raised by his grandmother until he was thirteen, when he moved to Lincoln, Illinois, to live with his mother and her husband, before the family eventually settled in Cleveland, Ohio.

INFLUENCES

• In November 1924, he moved to

Washington, D.C. Hughes's first book of poetry, The Weary Blues , was published by Alfred A. Knopf in 1926.

• Hughes, who claimed Paul Lawrence

Dunbar, Carl Sandburg, and Walt Whitman as his primary influences, is particularly known for his insightful, colorful portrayals of black life in America from the twenties through the sixties.

• He wanted to tell the stories of his people in ways that reflected their actual culture, including both their suffering and their love of music, laughter, and language itself.

Merry-Go-Round

(Colored child at carnival)

Where is the Jim Crow section

On this merry-go-round,

Mister, cause I want to ride?

Down South where I come from

White and colored

Can’t sit side by side.

Down South on the train

There’s a Jim Crow car.

On the bus we’re put in the back-

But there ain’t no back

To a merry-go-round!

Where’s the horse

For a kid that’s black?

“Merry-Go-Round” reveals the author’s belief that: a. Whites and blacks have reached equality b. Jim Crow laws were intended the rights of African Americans

c. The absurdity of segregation d. The racist nature of a merry-go-rounds

NOW THAT ’ S IMPRESSIVE

Langston wrote: sixteen books of poems, two novels, three collections of short stories, four volumes of "editorial" and "documentary" fiction, twenty plays, children's poetry, musicals and operas, three autobiographies, a dozen radio and television scripts and dozens of magazine articles.

In addition, he edited seven anthologies.

STYLE, BABY.

• Langston expressed pride in his heritage and voiced his displeasure with the oppression he witnessed.

• Many of his poems are from the point of view of African American women, especially older women.

• He also would often try to recreate the rhythms of contemporary jazz and blues in his poetry.

MOTHER TO SON

Well, son, I'll tell you:

Life for me ain't been no crystal stair.

It's had tacks in it,

And splinters,

And boards torn up,

And places with no carpet on the floor --

Bare.

But all the time

I'se been a-climbin' on,

And reachin' landin's,

And turnin' corners,

And sometimes goin' in the dark

Where there ain't been no light.

So boy, don't you turn back.

Don't you set down on the steps

'Cause you finds it's kinder hard.

Don't you fall now --

For I'se still goin', honey,

I'se still climbin',

And life for me ain't been no crystal stair.

The use of African American dialect in various works during the Harlem

Renaissance was used for all of the following EXCEPT:

a. To address the need for grammatical instruction b. To embody all aspects of the African

American community in a positive light c. To provide an authentic African

American voice in various works d.To emphasize the importance of culture in writing

RHYTHMS

• One of his favorite pastimes was sitting in the clubs listening to blues, jazz and writing poetry.

• Through these experiences a new rhythm emerged in his writing, and a series of poems such as "The

Weary Blues" were penned.

KEEP ON KEEPIN ON

• In 1925 he moved to

Washington, D.C., still spending more time in blues and jazz clubs.

• He said, "I tried to write poems like the songs they sang on

Seventh Street...

(these songs) had the pulse beat of the people who keep on going."

THE WEARY BLUES

BY LANGSTON HUGHES

Droning a drowsy syncopated tune,

Rocking back and forth to a mellow croon,

I heard a Negro play.

Down on Lenox Avenue the other night

By the pale dull pallor of an old gas light

He did a lazy sway . . .

He did a lazy sway . . .

To the tune o' those Weary Blues.

With his ebony hands on each ivory key

He made that poor piano moan with melody.

O Blues!

Swaying to and fro on his rickety stool

He played that sad raggy tune like a musical fool.

Sweet Blues!

Coming from a black man's soul.

O Blues!

In a deep song voice with a melancholy tone

I heard that Negro sing, that old piano moan –

"Ain't got nobody in all this world,

Ain't got nobody but ma self.

I's gwine to quit ma frownin'

And put ma troubles on the shelf."

Thump, thump, thump, went his foot on the floor.

He played a few chords then he sang some more –

"I got the Weary Blues

And I can't be satisfied.

Got the Weary Blues

And can't be satisfied –

I ain't happy no mo'

And I wish that I had died."

And far into the night he crooned that tune.

The stars went out and so did the moon.

The singer stopped playing and went to bed

While the Weary Blues echoed through his head.

He slept like a rock or a man that's dead.

FIGURE OF DIVERSITY

• A common theme in many of Langston’s writings was the difficulty of

African Americans of mixed ethnic backgrounds to find their place in the world.

• Langston himself was of mixed ethnicity.

"On my father's side, the white blood in his family came from a Jewish slave trader in Kentucky; and Sam Clay, a distiller of Scotch descent, living in Henry County, who was his father's father. So on my father's side both male greatgrandparents were white.”

“On my mother's side, I had a paternal great-grandfather named Quarles

- who was white and lived in Louisa County, Virginia, before the Civil

War, and who had several colored children by a colored housekeeper, who was his slave.”

“On my maternal grandmother's side, there was French and Indian blood. My grandmother looked like an Indian - with very long black hair.

She said she could lay claim to Indian land, but that she never wanted the government (or anybody else) to give her anything.”

MULATTO by Langston Hughes

Because I am the white man’s son- his own,

Bearing his bastard birth-mark on my face,

I will dispute his title to his throne,

Forever fight him for my rightful place.

There is a searing hate within my soul,

A hate that only kin can feel for kin,

A hate that makes me vigorous and whole,

And spurs me on increasingly to win.

Because I am my cruel father’s child,

My love of justice stirs me up to hate,

A warring Ishmaelite, unreconciled,

When falls the hour I shall not hesitate

Into my father’s heart to plunge the knife

To gain the utmost freedom that is life.

CROSS by Langston Hughes

My old man’s a white old man

And my old mother’s black.

If ever I cured my white old man

I take my curses back.

If ever I cursed my black old mother

And wished she were in hell,

I’m sorry for that evil wish

And now I wish her well

My old man died in a fine big house.

My ma died in a shack.

I wonder where I’m going to die,

Being neither white nor black?

All of the following describe Hughes’ perspective toward being bi-racial in the poems “Mulatto,” and “Cross”, EXCEPT:

a. Confusion b. Contentment c. Hatred d. Confrontation

HEY WALT, WHAT ABOUT ME?

I, TOO by Langston Hughes

I, too, sing America.

I am the darker brother.

They send me to eat in the kitchen

When company comes,

But I laugh,

And eat well,

And grow strong.

Tomorrow,

I'll be at the table

When company comes.

Nobody'll dare

Say to me,

"Eat in the kitchen,"

Then.

Besides,

They'll see how beautiful I am

And be ashamed--

I, too, am America.