Final report C2014/1285 (word)

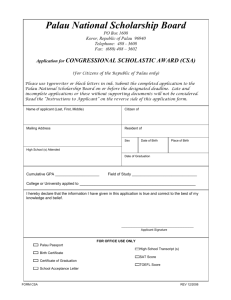

advertisement