Draft Agricultural Resources Appendix in Word 10-11-13

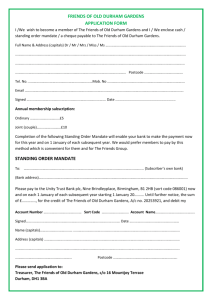

advertisement