Carnival and Lent - University of Warwick

advertisement

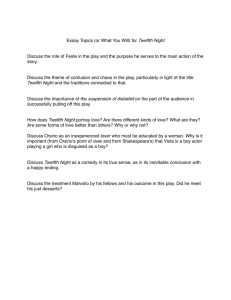

‘I am not what I am’ Carnival and Lent in Twelfth Night Looking forward and looking back: Janus and January ‘Twelfth Night Merrymaking in Farmer Shakeshaft’s Barn’ (Phiz, c. 1840) Recap: Carnival Shrove Tuesday May Games Misrule (Christmas – especially Twelfth Night) From Philip Stubbes, The Anatomie of Abuses (1583): ‘First, all the wildheads of the parish, conventing together, choose them a grand captain (of all mischief) whom they ennoble with the title of “my Lord of Misrule”, and him they crown with great solemnity, and adopt for their king. … And in this sort they go to the church (I say) and into the church (though the minister be at prayer or preaching) dancing and swinging their handkerchiefs over their heads in the church, like devils incarnate, with such a confused noise, that no man can hear his own voice.’ Recap: Carnival According to Michael Bristol: ‘Central to the experience of Carnival is a particular use of symbols, costumes and masks, in which the ordinary relationship between signifier and signified is disrupted and conventional meaning is parodied.’ (1983: 641) For Mikhail Bakhtin, carnival ‘offers the chance to have a new outlook on the world, to realize the relative nature of all that exists, and to enter a completely new order of things’ (1965: 34). In the carnival of the Renaissance period, says Bakhtin, ‘the world is seen anew, no less (and perhaps more) profoundly than when seen from the serious standpoint’ (1965: 66). Recap: Carnival As we saw last week, the Puritans of the period took a dim view of both carnival and theatre: ‘… some spend the Sabbath day (for the most part) in frequenting of bawdy stage-plays and interludes, in maintaining Lords of Misrule (for so they call a certain kind of play which they use), May games, church-ales, feasts, and wakes: in piping, dancing, dicing, carding, bowling, tennis-playing: in bear-baiting, cockfighting, hawking, hunting, and such like; … whereby the Lord God is dishonoured, his Sabbath violated, his word neglected, his sacraments contemned, and his people marvellously corrupted and carried away from true virtue and godliness.’ (Philip Stubbes, The Anatomie of Abuses, 1583) Carnival and the Elizabethan stage Robert Weimann argues that ‘although the [carnivalesque] ceremonies were gradually discontinued, their spirit survived in the gaiety, the “immoderate and disordinate Joye,” of the Elizabethan clown, jig dancer, and “ieaster”’ (1987: 23-4): ‘…his study is to coin bitter jests, or to show antique motions, or to sing bawdy sonnets and ballads: give him a little wine in his head, he is continually flearing and making of mouths; he laughs intemperately at every little occasion, and dances about the houses, leaps over tables, outskips men’s heads, trips up his companions’ heels, burns sack with a candle, and hath all the feats of a Lord of Misrule in the country.’ (Thomas Lodge, Wits Miserie, 1596) Twelfth Night and carnival Bakhtin describes ‘the essential carnival element in the organization of Shakespeare’s drama’: ‘This does not merely concern the secondary, clownish motives of his plays. The logic of crownings and uncrownings, in direct or indirect form, organizes the serious elements also.’ (1965: 275) Twelfth Night’s title, of course, has festive and carnivalesque associations. Sebastian, towards the end of the play, asks, ‘Are all the people mad?’ (4.1.26) Twelfth Night and carnival In Bakhtinian fashion, Twelfth Night might be characterised as a play which explodes traditional categorisations and hierarchies. As Karin S. Coddon argues: ‘In Twelfth Night demarcations between male and female, master and servant, libertine and moralist come into festive – and not so festive – collision.’ (Coddon 1993: 309) Carnival and Lent (Pieter Bruegel, 1559) Sir Toby Belch MARIA. …you must confine yourself within the modest limits of order. SIR TOBY. Confine? I’ll confine myself no finer than I am. These clothes are good enough to drink in, and so be these boots too; an they be not, let them hang themselves in their own straps. (1.3.7-12) Compare Falstaff: ‘out of all order, out of all compass’ (1 Henry IV, 3.3.19) Twelfth Night, Filter, 2008 (2010 revival) Sir Toby Belch Lord of Misrule? ‘I am sure care’s an enemy to life’ (1.3.2) Ambiguous identity Terry Eagleton argues that Sir Toby ‘is a rampant hedonist, complacently anchored in his body, falling at once “beyond” the symbolic order of society in his verbal anarchy, and “below” it in his carnivalesque refusal to submit his body to social control’ (1986: 32). Twelfth Night, Filter, 2008 (2010 revival) Sir Toby Belch ‘The grotesque body’ ‘Laughter degrades and materializes… To degrade also means to concern oneself with the lower stratum of the body, the life of the belly and the reproductive organs’ (Bakhtin 1965: 20-1). Twelfth Night, Filter, 2008 (2010 revival) A twist on the morality play? Remember the Vices from Mankind: NOW-A-DAYS. Leap about lively! Thou art a valiant man; Let us be merry while we be here! NOUGHT. Shall I break my neck to show you sport? NOW-A-DAYS. Therefore, ever beware of thy report! NOUGHT. I beshrew ye all! Here is a shrewd sort; Have thereat then, with a merry cheer! Here they dance MERCY. Do way! do way this revel, sirs! Do way! NOW-A-DAYS. Do way, good Adam? Do way? This is no part of thy play. (75-83) A twist on the morality play? SIR ANDREW. Shall we set about some revels? SIR TOBY. What shall we do else – were we not born under Taurus? SIR ANDREW. Taurus? That’s sides and heart. SIR TOBY. No, sir, it is legs and thighs: let me see thee caper. Ha, higher! Ha, ha, excellent! (1.3.130-7) MALVOLIO. My masters, are you mad? Or what are you? Have you no wit, manners, nor honesty, but to gabble like tinkers at this time of night? Do ye make an alehouse of my lady’s house, that ye squeak out your coziers’ catches without any mitigation or remorse of voice? Is there no respect of place, persons, nor time in you? SIR TOBY. We did keep time, sir, in our catches. Sneck up! (2.3.83-90) Malvolio MARIA. Marry, sir, sometimes he is a kind of Puritan. SIR ANDREW. O, if I thought that I’d beat him like a dog. SIR TOBY BELCH. What, for being a Puritan? Thy exquisite reason, dear knight. SIR ANDREW. I have no exquisite reason for’t, but I have reason good enough. (2.3.135-40) I, Malvolio, Tim Crouch, 2011 Malvolio Malvolio as anti-theatrical Puritan: MALVOLIO. I marvel your ladyship takes delight in such a barren rascal… I protest, I take these wise men, that crow so at these set kind of fools, no better than the fools’ zanies. (1.5.79-85) SIR TOBY. Dost thou think because thou art virtuous, there shall be no more cakes and ale? (2.3.110-11) Of course, the festive world of the play turns the Puritan Malvolio into his very opposite… OLIVIA Why, this is very midsummer madness. (3.4.54) The Malvolio paradox FABIAN. If this were played upon a stage, now, I could condemn it as an improbable fiction. (3.4.125-6) Director Tim Carroll describes Malvolio’s gulling scene as a ‘game’: it asks its audience ‘to be complicit in accepting something which is literally unbelievable’ (2008: 38). There are generally two games being played concurrently during this sequence: the onstage observers’ game is to remain hidden from Malvolio whilst indulging in behaviours that jeopardise their cover; at the same time, the object of Malvolio’s game is to persuade both himself and the audience that the words of the letter refer to him. The Malvolio paradox Donald Sinden documents his performance in John Barton’s 1969 production in his chapter of Players of Shakespeare 1, noting numerous playful exchanges with the audience. For example, when Malvolio reads the word ‘steward’ in the letter, he shows it to the audience: ‘They obviously don’t believe him, so he shows them the very word and mouths it a second time (laugh 3). Fools! He is patently wasting his time on them – they only laugh.’ (1985: 58) Jonathan Holmes points out that Sinden ‘predicates his characterisation on the play-acting of those he is addressing, which as his account makes clear includes the audience as much as, and perhaps more than, his onstage addressees’ (2004: 29-30). Feste FESTE. I am gone, sir, And anon, sir, I’ll be with you again, In a trice, Like to the old Vice, Your need to sustain… (4.2.123-8) The social status of fools (and indeed of players) is at once ‘both high and low’ (2.3.40). A wandering figure, Feste belongs both to the locus of the play world and the platea of the Elizabethan audience. Twelfth Night, Propeller, 2012 Feste VIOLA. Art not thou the Lady Olivia’s fool? FESTE. No indeed, sir, the Lady Olivia has no folly… I am indeed not her fool, but her corrupter of words. (3.1.30-5) ‘Feste’s entrance … is coloured not only by the unauthorized absence from Olivia’s household, but also by his defiant resistance (‘Let her hang me’) to Maria’s interrogations about his whereabouts, even under the threat of hanging or unemployment.’ (Coddon 1993: 315) Twelfth Night, Propeller, 2012 Wise fools and foolish wits ‘This fellow is wise enough to play the fool’ (3.1.59) ‘Better a witty fool, than a foolish wit’ (1.5.32-3) Feste and Olivia’s ‘Take the fool away’ exchange (1.5.35-68) disrupts categories of folly and wisdom in a carnivalesque manner. This same disruption is later brought to bear on Malvolio: MALVOLIO. Fool, there was never a man so notoriously abused. I am as well in my wits, fool, as thou art. FESTE. But as well? Then you are mad indeed, if you be no better in your wits than a fool. (4.2.89-92) OLIVIA. Alas, poor fool, how have they baffled thee! (5.1.366) Carnival and Lent in Twelfth Night What is love? ’tis not hereafter; Present mirth hath present laughter; What’s to come is still unsure: In delay there lies no plenty; Then come kiss me, sweet and twenty, Youth’s a stuff will not endure. Twelfth Night, dir. Trevor Nunn, 1996 (2.3.46-51) Carnival and Lent in Twelfth Night The play stages a conflict between the force of selfdenial and the more joyful spirit of liberation. VIOLA. …She pined in thought, And with a green and yellow melancholy She sat like patience on a monument, Smiling at grief. (2.4.112-15) OLIVIA. Why then, methinks ’tis time to smile again. […] The clock upbraids me with the waste of time. (3.1.1259) Gender inversion Three couples exhibit same-sex attraction in the play: Olivia/Viola, Orsino/Cesario, and Antonio/Sebastian. Casey Charles argues that ‘…this theme functions neither as an uncomplicated promotion of a modern category of sexual orientation nor, from a more traditional perspective, as an ultimately contained representation of the licensed misrule of saturnalia. The representation of homoerotic attraction in Twelfth Night functions rather as a means of dramatizing the socially constructed basis of a sexuality that is determined by gender identity.’ (Charles 1997: 122) Gender inversion Complicating this, of course, is the fact that Viola-as-Cesario would have been played by a boy actor. Boy actors already challenged Elizabethan England’s sense of stable gender identities: anti-theatricalists frequently complained that boys dressed as women provoked illicit sexual desire. Stubbes again: ‘Our apparel was given us as a sign distinctive to discern betwixt sex and sex, and therefore one to wear the apparel of another sex is to participate with the same, and to adulterate the verity of his own kind.’ VIOLA. Disguise, I see, thou art a wickedness Wherein the pregnant enemy does much. (2.2.27-8) Twelfth Night as saturnalia? C. L. Barber: ‘The most fundamental distinction the play brings home to us is the difference between men and women. To say this may seem to labour the obvious; for what love story does not emphasize this difference? But the disguising of a girl as a boy in Twelfth Night is exploited so as to renew in a special way our sense of the difference. Just as a saturnalian reversal of social roles need not threaten the social structure, but can serve instead to consolidate it, so a temporary, playful reversal of sexual roles can renew the meaning of the normal relation.’ (245) Viola as liminal figure Viola makes it clear that she is ‘acting a part’: VIOLA. I can say little more than I have studied, and that question’s out of my part. (1.5.171-2) OLIVIA. Are you a comedian? VIOLA. No, my profound heart; and yet – by the very fangs of malice I swear – I am not that I play. (1.5.175-7) Later, however, this becomes a more profound identity crisis: VIOLA. I am not what I am. (3.1.139) Viola as liminal figure ORSINO. Your master quits you, and for your service done him So much against the mettle of your sex, So far beneath your soft and tender breeding, And since you called me master for so long, Here is my hand. You shall from this time be Your master’s mistress. (5.1.318-23) ORSINO. …Cesario, come – For so you shall be while you are a man; But when in other habits you are seen, Orsino’s mistress and his fancy’s queen. (5.1.381-4) Viola as liminal figure ‘…in her hermaphroditic capacity as man and woman… [Viola] collapses the polarities upon which heterosexuality is based by becoming an object of desire whose ambiguity renders the distinction between homoand hetero-erotic attraction difficult to decipher.’ (Charles 1997: 127-8) Twelfth Night publicity image, Propeller, 2007 Twelfth Night’s ending: saturnalian or subversive? ‘If in Twelfth Night the aristocratic order is ostensibly reasserted in the pairings of Orsino/Viola and Oliva/Sebastian, the refusal of the play’s closing to recuperate two of its most disorderly subjects – Malvolio and Feste – suggests rather less than a wholesale endorsement of the privileges of rank and hierarchy.’ (Coddon 1993: 309) ‘The so-called “festive comedy” concludes rather ominously; if indeed “the whirligig of time brings in his revenges,” it is difficult to dismiss Malvolio’s parting threat as merely one sour note troubling an otherwise stable social hierarchy.’ (Coddon 1993: 322) References Bakhtin, Mikhail (1965) Rabelais and His World, trans. H. Iswolsky, Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Barber, C. L. (1972) Shakespeare’s Festive Comedy: A Study of Form and its Relation to Social Custom, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Bristol, Michael D. (1983) ‘Carnival and the Institutions of Theatre in Elizabethan England’, ELH, 50: 4, 637-654. Carroll, Tim (2008) ‘Practising behaviour to his own shadow’, in Christie Carson & Farah Karim-Cooper [eds] Shakespeare’s Globe: A Theatrical Experiment, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 37-44. Charles, Casey (1997) ‘Gender Trouble in Twelfth Night’, Theatre Journal, 49: 2, 121-141. References Coddon, Karin S. (1993) ‘“Slander in an Allow’d Fool”: Twelfth Night’s Crisis of the Aristocracy’, Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, 33: 2, 309-325. Eagleton, Terry (1986) William Shakespeare, London: Basil Blackwell. Holmes, Jonathan (2004) Merely Players?: Actors’ Accounts of Performing Shakespeare, London & New York: Routledge. Sinden, Donald (1985) ‘Malvolio in Twelfth Night’, in Philip Brockbank [ed.] Players of Shakespeare 1, 41-66. Weimann, R. (1987) Shakespeare and the Popular Tradition in the Theater: Studies in the Social Dimension of Dramatic Form and Function, Baltimore/London: Johns Hopkins University Press.