Early Virgnia and the Chesapeake PPT

advertisement

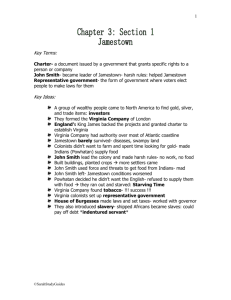

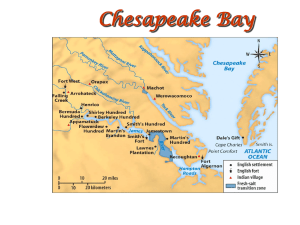

Virginia 1607-1660 England and the New World • • • • • • Despite the cultural growth and the increasing sense of national identity of the Elizabethan Age (1558-1603), England remained a small and relatively poor country on the fringe of Europe. England had only a fraction of the population of its rivals, France and Spain. In 1600, France’s population stood at 20 million, Spain’s at 11 million and England at barely 4 million. In the 16th century, England’s stability was undermined by internal religious conflict. After the English Reformation began in the 1530s, England oscillated between the Anglicanism of Henry VIII, radical Protestantism under Edward VI, a return to Roman Catholicism under Mary I and finally an uneasy Protestant settlement under Elizabeth I. Puritans and Catholics were the “outsiders” of English society. England’s expansion outside the island of Britain began with the conquest of Ireland in the late 16th century. The ruthless brutality of the English conquest in Ireland would serve as a blueprint for expansion into North America. England’s Economic & Social Crisis • • • • • • • • As if religious divisions weren’t bad enough, England’s economic and social problems worsened. An economic downturn was exacerbated by the “enclosure” movement. Hundreds of thousands of desperate and displaced “strolling poor” wandered the countryside and eventually into the cities in search of food and work. These “masterless men” posed a growing threat to England’s social stability. What to do? Thomas More’s Utopia, 1519. Richard Hakluyt’s A Discourse Concerning Western Planting, 1584. Hakluyt made a compelling argument: start colonizing! Colonies in North America would provide land and work for the poor, a naval force along the east coast would check Spanish power in the New World, profits from colonial investments would boost England’s economy and England could spread Protestantism to counter Spanish Catholicism. Hakluyt called his plan “The Glory of England’s Future.” King James I (1603-1625) King Charles I (1625-1649) John White’s 1580s renditions of Powhatan villages. The illustration on the left is the most accurate. The one on the right shows a center “street” and crops growing in neat rows in segregated fields. The Powhatans had no need for wide streets. They grew corn, beans and squash all tangled together which was more efficient and productive for these crops than the English method. For meat, they hunted. Indians planted their crops without horses or plows and so would most of the English. Consider the cost of transporting and feeding horses on a three-month voyage across the Atlantic Ocean. Powhatan’s Virginia The Powhatan Confederacy controlled most of what is now the eastern half of Virginia. It was one of the largest and most powerful Indian nations on the East Coast. The Powhatans subjugated and ruthlessly exploited their neighbors, sometimes forcibly moving “disloyal” tribes to new areas or exterminating them altogether. At first, the Powhatans were not intimidated by the English. They saw them as a well-armed, but otherwise weak and disorganized “tribe” who could be manipulated and used to maintain control over their conquests. John Smith’s Map, 1612 The map shows the locations of dozens of Indian settlements and while not “exact,” it’s surprisingly accurate. Archaeologists still use the map today to help identify and locate pre-contact Indian sites. The Powhatans resisted English expansion for over four decades. There were three major AngloPowhatan wars, the first lasting from 1610 until 1614. In 1622, a coordinated Powhatan attack killed hundreds of English and nearly ended the Virginia colony. In 1632, the English constructed an earth and wooden palisade across the entire James-York peninsula to defend against the Indians. Gov. Wm. Berkeley and the English crushed a final Powhatan uprising in 1644 and forced the defeated Indians onto reservations, America’s first. By 1650, the Powhatans had been driven from the entire peninsula, but a profitable English trade in deerskins with Indians further inland continued for decades. The Topography of Tidewater Virginia Promotional pamphlet and an early depiction of Jamestown and its triangular palisade. Jamestown, ca. 1640 Tobacco was highly labor intensive. One indentured servant could maintain 3-4 acres. Between February and November the tobacco had to be seeded, re-planted, topped, wormed, suckered, picked, hung, dried, cured, rolled into hands, packed, prized and shipped. Tobacco being dried and cured Prizing the tobacco and transporting on a rolling road Preparing the hogsheads for shipment to England In 1618, the Va. Company introduced the “headright” system to encourage the importation of labor as tobacco production spiraled upward. A planter received 50 acres of land for each individual he paid to have transported to the colony. Most were indentured servants. Between 1607 and 1675 as many as 3 out of 4 English emigrants to the Chesapeake arrived as indentured servants. Some planters amassed holdings of tens of thousands of acres. English Virginians lived on widely dispersed farms and plantations. There were few, if any, towns. Wealthy planters occupied the riverfront lands with middling and small farmers settling the interior of the Virginia peninsulas. Impermanent architecture: a 17th century Virginia house. Tobacco cultivation exhausted Virginia’s soil rapidly. A tobacco field could only sustain crops for three to four years. Thus, new land had to be cleared frequently and it was not uncommon for planters to move their operations several miles each time. They saw little sense in spending large sums on houses and barns that would be occupied for a relatively few years. The Allen House (aka “Bacon’s Castle”) – built 1665 in Surry County, Virginia. One of only three or four 17th-century buildings still standing in Virginia today. By comparison, New England has hundreds of 17th-century structures.