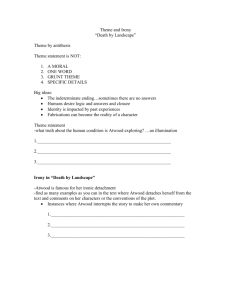

MARGARET ATWOOD Regarded as one of Canada's finest living

advertisement

MARGARET ATWOOD Regarded as one of Canada’s finest living writers, Margaret Atwood is a poet, novelist, story writer, essayist, and environmental activist. Her books have received critical acclaim in the United States, Europe, and her native Canada, and she has received numerous literary awards, including the Booker Prize, the Arthur C. Clarke Award, and the Governor General’s Award, twice. Atwood’s critical popularity is matched by her popularity with readers; her books are regularly bestsellers. Atwood first came to public attention as a poet in the 1960s with her collections Double Persephone (1961), winner of the E.J. Pratt Medal, and The Circle Game(1964), winner of a Governor General’s award. These two books marked out the terrain her subsequent poetry has explored. Double Persephone dramatizes the contrasts between life and art, as well as natural and human creations. The Circle Game takes this opposition further, setting such human constructs as games, literature, and love against the instability of nature. Sherrill Grace, writing in Violent Duality: A Study of Margaret Atwood, identified the central tension in all of Atwood’s work as “the pull towards art on one hand and towards life on the other.” Atwood “is constantly aware of opposites—self/other, subject/ object, male/female, nature/man—and of the need to accept and work within them,” Grace explained. Linda W. Wagner, writing in The Art of Margaret Atwood: Essays in Criticism, also saw the dualistic nature of Atwood’s poetry, asserting that “duality [is] presented as separation” in her work. This separation leads her characters to be isolated from one another and from the natural world, resulting in their inability to communicate, to break free of exploitative social relationships, or to understand their place in the natural order. “In her early poetry,” Gloria Onley wrote in the West Coast Review, Atwood “is acutely aware of the problem of alienation, the need for real human communication and the establishment of genuine human community—real as opposed to mechanical or manipulative; genuine as opposed to the counterfeit community of the body politic.” 1 Suffering is common for the female characters in Atwood’s poems, although they are never passive victims. Atwood’s poems, West Coast Review contributor Onley maintained, concern “modern woman’s anguish at finding herself isolated and exploited (although also exploiting) by the imposition of a sex role power structure.” Atwood explained to Judy Klemesrud in the New York Times that her suffering characters come from real life: “My women suffer because most of the women I talk to seem to have suffered.” Although she became a favorite of feminists, Atwood’s popularity in the feminist community was unsought. “I began as a profoundly apolitical writer,” she told Lindsy Van Gelder of Ms., “but then I began to do what all novelists and some poets do: I began to describe the world around me.” Atwood’s 1995 book of poetry, Morning in the Burned House, “reflects a period in Atwood’s life when time seems to be running out,” observed John Bemrose inMaclean’s. Noting that many of the poems address grief and loss, particularly in relationship to her father’s death and a realization of her own mortality, Bemrose added that the book “moves even more deeply into survival territory.” Bemrose further suggested that in this book, Atwood allows the readers greater latitude in interpretation than in her earlier verse: “Atwood uses grief…to break away from that airless poetry and into a new freedom.” A selection of Atwood’s poems was released as Eating Fire: Selected Poems 1965-1995 in 1998. Showing the arc of Atwood’s poetics, the volume was praised by Scotland on Sunday for its “lean, symbolic, thoroughly Atwoodesque prose honed into elegant columns.” Atwood’s 2007 collection, The Door, was her first new volume of poems in a decade. Reviewing the book for the Guardian, the noted literary critic Jay Parini maintained that Atwood’s “northern” poetic climate is fully on view, “full of wintry scenes, harsh autumnal rain, splintered lives, and awkward relationships. Against this landscape, she draws figures of herself.” Parini found Atwood using irony, the conventions of confessional verse, political attitudes and gestures, as well as moments of ars poetica throughout the collection. “There is a pleasing consistency in these poems,” he wrote “which are always written in a fluent free verse, in robust, clear language. Atwood’s wit and humour are pervasive, and few of the poems end without an ironic twang.” Atwood’s interest in women and female experience also emerges clearly in her novels, particularly in The Edible Woman (1969), Surfacing (1972), Life before Man (1979), Bodily Harm (1981), and The Handmaid’s Tale (1985). Even later novels such as The Robber Bride (1993) and Alias Grace (1996) feature female characters defined by their intelligence and complexity. By far Atwood’s most famous early novel, The Handmaid’s Tale also presages her later novels of scientific dystopia and environmental disaster like Oryx and Crake (2003) and The Year of the Flood(2009). Rather than “science fiction,” Atwood uses the term “speculative fiction” to describe her project in these novels. The Handmaid’s Tale is dominated by an unforgiving view of patriarchy and its legacies. As Barbara Holliday 2 wrote in the Detroit Free Press, Atwood “has been concerned in her fiction with the painful psychic warfare between men and women. In The Handmaid’s Tale...she casts subtlety aside, exposing woman’s primal fear of being used and helpless.” Atwood, however, believes that her vision is not far from reality. Speaking to Battiata, Atwood noted that “The Handmaid’s Tale does not depend upon hypothetical scenarios, omens, or straws in the wind, but upon documented occurrences and public pronouncements; all matters of record.” Atwood’s next few books deal less with speculative worlds and more with history, literary convention, and narrative hi-jinx. In The Robber Bride, Atwood again explores women’s issues and feminist concerns, this time concentrating on women’s relationships with each other—both positive and negative. Inspired by the Brothers Grimm’s fairy tale “The Robber Bridegroom,” the novel chronicles the relationships of college friends Tony, Charis, and Roz with their backstabbing classmate Zenia. Lorrie Moore, writing in the New York Times Book Review, called The Robber Bride“Atwood’s funniest and most companionable book in years,” adding that its author “retains her gift for observing, in poetry, the minutiae specific to the physical and emotional lives of her characters.” Alias Grace represents Atwood’s first venture into historical fiction, but the book has much in common with her other works in its contemplation of “the shifting notions of women’s moral nature” and “the exercise of power between men and women,” wrote Maclean’s contributor Diane Turbide. Several reviewers found Grace, a woman accused of murdering her employer and his wife but who claims amnesia, a complicated and compelling character. Atwood is known for her strong support of causes: feminism, environmentalism, social justice. In Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature (1972), Atwood discerns a uniquely Canadian literature, distinct from its American and British counterparts. Canadian literature, she argues, is primarily concerned with victims and with the victim’s ability to survive unforgiving circumstances. In the way other countries or cultures focus around a unifying symbol—America’s frontier, England’s island—Canada and Canadian literature orientate around survival. Several critics find that Atwood’s own work exemplifies this primary theme of Canadian literature. Her examination of destructive gender roles and her nationalistic concern over the subordinate role Canada plays to the United States are variations on the victor/victim theme. Atwood believes a writer must consciously work within his or her nation’s literary tradition, and her own work closely parallels the themes she sees as common to the Canadian literary tradition. 3 A Sad Child You're sad because you're sad. It's psychic. It's the age. It's chemical. Go see a shrink or take a pill, or hug your sadness like an eyeless doll you need to sleep. Well, all children are sad but some get over it. Count your blessings. Better than that, buy a hat. Buy a coat or pet. Take up dancing to forget. Forget what? Your sadness, your shadow, whatever it was that was done to you the day of the lawn party when you came inside flushed with the sun, your mouth sulky with sugar, in your new dress with the ribbon and the ice-cream smear, and said to yourself in the bathroom, I am not the favorite child. My darling, when it comes right down to it and the light fails and the fog rolls in and you're trapped in your overturned body under a blanket or burning car, and the red flame is seeping out of you and igniting the tarmac beside you head or else the floor, or else the pillow, none of us is; or else we all are. 4 A Visit* Gone are the days when you could walk on water. When you could walk. The days are gone. Only one day remains, the one you're in. The memory is no friend. It can only tell you what you no longer have: a left hand you can use, two feet that walk. All the brain's gadgets. Hello, hello. The one hand that still works grips, won't let go. That is not a train. There is no cricket. Let's not panic. Let's talk about axes, which kinds are good, the many names of wood. This is how to build a house, a boat, a tent. No use; the toolbox refuses to reveal its verbs; the rasp, the plane, the awl, revert to sullen metal. 5 Do you recognize anything? I said. Anything familiar? Yes, you said. The bed. Better to watch the stream that flows across the floor and is made of sunlight, the forest made of shadows; better to watch the fireplace which is now a beach. 6 Backdrop Addresses Cowboy Starspangled cowboy sauntering out of the almostsilly West, on your face a porcelain grin, tugging a papier-mache cactus on wheels behind you with a string, you are innocent as a bathtub full of bullets. Your righteous eyes, your laconic trigger-fingers people the streets with villains: as you move, the air in front of you blossoms with targets and you leave behind you a heroic trail of desolation: beer bottles slaughtered by the side of the road, birdskulls bleaching in the sunset. I ought to be watching from behind a cliff or a cardboard storefront when the shooting starts, hands clasped in admiration, but I am elsewhere. Then what about me 7 what about the I confronting you on that border you are always trying to cross? I am the horizon you ride towards, the thing you can never lasso I am also what surrounds you: my brain scattered with your tincans, bones, empty shells, the litter of your invasions. I am the space you desecrate as you pass through. 8 Bored All those times I was bored out of my mind. Holding the log while he sawed it. Holding the string while he measured, boards, distances between things, or pounded stakes into the ground for rows and rows of lettuces and beets, which I then (bored) weeded. Or sat in the back of the car, or sat still in boats, sat, sat, while at the prow, stern, wheel he drove, steered, paddled. It wasn't even boredom, it was looking, looking hard and up close at the small details. Myopia. The worn gunwales, the intricate twill of the seat cover. The acid crumbs of loam, the granular pink rock, its igneous veins, the sea-fans of dry moss, the blackish and then the graying bristles on the back of his neck. Sometimes he would whistle, sometimes I would. The boring rhythm of doing things over and over, carrying the wood, drying the dishes. Such minutiae. It's what the animals spend most of their time at, ferrying the sand, grain by grain, from their tunnels, shuffling the leaves in their burrows. He pointed such things out, and I would look at the whorled texture of his square finger, earth under the nail. Why do I remember it as sunnier all the time then, although it more often rained, and more birdsong? I could hardly wait to get the hell out of there to anywhere else. Perhaps though boredom is happier. It is for dogs or groundhogs. Now I wouldn't be bored. Now I would know too much. Now I would know. 9 Flying Inside Your Own Body Your lungs fill & spread themselves, wings of pink blood, and your bones empty themselves and become hollow. When you breathe in you’ll lift like a balloon and your heart is light too & huge, beating with pure joy, pure helium. The sun’s white winds blow through you, there’s nothing above you, you see the earth now as an oval jewel, radiant & seablue with love. It’s only in dreams you can do this. Waking, your heart is a shaken fist, a fine dust clogs the air you breathe in; the sun’s a hot copper weight pressing straight down on the think pink rind of your skull. It’s always the moment just before gunshot. You try & try to rise but you cannot. 10 Habitation Marriage is not a house or even a tent it is before that, and colder: the edge of the forest, the edge of the desert the unpainted stairs at the back where we squat outside, eating popcorn the edge of the receding glacier where painfully and with wonder at having survived even this far we are learning to make fire 11 Helen of Troy Does Countertop Dancing* The world is full of women who'd tell me I should be ashamed of myself if they had the chance. Quit dancing. Get some self-respect and a day job. Right. And minimum wage, and varicose veins, just standing in one place for eight hours behind a glass counter bundled up to the neck, instead of naked as a meat sandwich. Selling gloves, or something. Instead of what I do sell. You have to have talent to peddle a thing so nebulous and without material form. Exploited, they'd say. Yes, any way you cut it, but I've a choice of how, and I'll take the money. I do give value. Like preachers, I sell vision, like perfume ads, desire or its facsimile. Like jokes or war, it's all in the timing. I sell men back their worse suspicions: that everything's for sale, and piecemeal. They gaze at me and see a chain-saw murder just before it happens, when thigh, ass, inkblot, crevice, tit, and nipple are still connected. Such hatred leaps in them, my beery worshippers! That, or a bleary hopeless love. Seeing the rows of heads and upturned eyes, imploring but ready to snap at my ankles, I understand floods and earthquakes, and the urge to step on ants. I keep the beat, and dance for them because they can't. The music smells like foxes, crisp as heated metal 12 searing the nostrils or humid as August, hazy and languorous as a looted city the day after, when all the rape's been done already, and the killing, and the survivors wander around looking for garbage to eat, and there's only a bleak exhaustion. Speaking of which, it's the smiling tires me out the most. This, and the pretence that I can't hear them. And I can't, because I'm after all a foreigner to them. The speech here is all warty gutturals, obvious as a slab of ham, but I come from the province of the gods where meanings are lilting and oblique. I don't let on to everyone, but lean close, and I'll whisper: My mother was raped by a holy swan. You believe that? You can take me out to dinner. That's what we tell all the husbands. There sure are a lot of dangerous birds around. Not that anyone here but you would understand. The rest of them would like to watch me and feel nothing. Reduce me to components as in a clock factory or abattoir. Crush out the mystery. Wall me up alive in my own body. They'd like to see through me, but nothing is more opaque than absolute transparency. Look--my feet don't hit the marble! Like breath or a balloon, I'm rising, I hover six inches in the air in my blazing swan-egg of light. You think I'm not a goddess? Try me. This is a torch song. Touch me and you'll burn. 13 In the Secular Night In the secular night you wander around alone in your house. It's two-thirty. Everyone has deserted you, or this is your story; you remember it from being sixteen, when the others were out somewhere, having a good time, or so you suspected, and you had to baby-sit. You took a large scoop of vanilla ice-cream and filled up the glass with grapejuice and ginger ale, and put on Glenn Miller with his big-band sound, and lit a cigarette and blew the smoke up the chimney, and cried for a while because you were not dancing, and then danced, by yourself, your mouth circled with purple. Now, forty years later, things have changed, and it's baby lima beans. It's necessary to reserve a secret vice. This is what comes from forgetting to eat at the stated mealtimes. You simmer them carefully, drain, add cream and pepper, and amble up and down the stairs, scooping them up with your fingers right out of the bowl, talking to yourself out loud. You'd be surprised if you got an answer, but that part will come later. There is so much silence between the words, you say. You say, The sensed absence of God and the sensed presence amount to much the same thing, only in reverse. You say, I have too much white clothing. You start to hum. Several hundred years ago this could have been mysticism or heresy. It isn't now. Outside there are sirens. Someone's been run over. The century grinds on. 14 Is/Not** Love is not a profession genteel or otherwise sex is not dentistry the slick filling of aches and cavities you are not my doctor you are not my cure, nobody has that power, you are merely a fellow/traveller Give up this medical concern, buttoned, attentive, permit yourself anger and permit me mine which needs neither your approval nor your suprise which does not need to be made legal which is not against a disease but agaist you, which does not need to be understood or washed or cauterized, which needs instead to be said and said. Permit me the present tense. 15 More and More More and more frequently the edges of me dissolve and I become a wish to assimilate the world, including you, if possible through the skin like a cool plant's tricks with oxygen and live by a harmless green burning. I would not consume you or ever finish, you would still be there surrounding me, complete as the air. Unfortunately I don't have leaves. Instead I have eyes and teeth and other non-green things which rule out osmosis. So be careful, I mean it, I give you fair warning: This kind of hunger draws everything into its own space; nor can we talk it all over, have a calm rational discussion. There is no reason for this, only a starved dog's logic about bones. 16 Morning in the Burned House In the burned house I am eating breakfast. You understand: there is no house, there is no breakfast, yet here I am. The spoon which was melted scrapes against the bowl which was melted also. No one else is around. Where have they gone to, brother and sister, mother and father? Off along the shore, perhaps. Their clothes are still on the hangers, their dishes piled beside the sink, which is beside the woodstove with its grate and sooty kettle, every detail clear, tin cup and rippled mirror. The day is bright and songless, the lake is blue, the forest watchful. In the east a bank of cloud rises up silently like dark bread. I can see the swirls in the oilcloth, I can see the flaws in the glass, those flares where the sun hits them. I can't see my own arms and legs or know if this is a trap or blessing, finding myself back here, where everything in this house has long been over, kettle and mirror, spoon and bowl, including my own body, including the body I had then, 17 including the body I have now as I sit at this morning table, alone and happy, bare child's feet on the scorched floorboards (I can almost see) in my burning clothes, the thin green shorts and grubby yellow T-shirt holding my cindery, non-existent, radiant flesh. Incandescent. 18 Night Poem There is nothing to be afraid of, it is only the wind changing to the east, it is only your father the thunder your mother the rain In this country of water with its beige moon damp as a mushroom, its drowned stumps and long birds that swim, where the moss grows on all sides of the trees and your shadow is not your shadow but your reflection, your true parents disappear when the curtain covers your door. We are the others, the ones from under the lake who stand silently beside your bed with our heads of darkness. We have come to cover you with red wool, with our tears and distant whipers. You rock in the rain's arms the chilly ark of your sleep, while we wait, your night father and mother with our cold hands and dead flashlight, knowing we are only the wavering shadows thrown by one candle, in this echo you will hear twenty years later. 19 Postcards I'm thinking about you. What else can I say? The palm trees on the reverse are a delusion; so is the pink sand. What we have are the usual fractured coke bottles and the smell of backed-up drains, too sweet, like a mango on the verge of rot, which we have also. The air clear sweat, mosquitoes & their tracks; birds, blue & elusive. Time comes in waves here, a sickness, one day after the other rolling on; I move up, it's called awake, then down into the uneasy nights but never forward. The roosters crow for hours before dawn, and a prodded child howls & howls on the pocked road to school. In the hold with the baggage there are two prisoners, their heads shaved by bayonets, & ten crates of queasy chicks. Each spring there's race of cripples, from the store to the church. This is the sort of junk I carry with me; and a clipping about democracy from the local paper. Outside the window they're building the damn hotel, nail by nail, someone's crumbling dream. A universe that includes you can't be all bad, but does it? At this distance you're a mirage, a glossy image fixed in the posture 20 of the last time I saw you. Turn you over, there's the place for the address. Wish you were here. Love comes in waves like the ocean, a sickness which goes on & on, a hollow cave in the head, filling & pounding, a kicked ear. 21 Provisions What should we have taken with us? We never could decide on that; or what to wear, or at what time of year we should make the journey So here we are in thin raincoats and rubber boots On the disastrous ice, the wind rising Nothing in our pockets But a pencil stub, two oranges Four Toronto streetcar tickets and an elastic band holding a bundle of small white filing cards printed with important facts. 22 Sekhmet, the Lion-headed Goddess of War He was the sort of man who wouldn't hurt a fly. Many flies are now alive while he is not. He was not my patron. He preferred full granaries, I battle. My roar meant slaughter. Yet here we are together in the same museum. That's not what I see, though, the fitful crowds of staring children learning the lesson of multicultural obliteration, sic transit and so on. I see the temple where I was born or built, where I held power. I see the desert beyond, where the hot conical tombs, that look from a distance, frankly, like dunces' hats, hide my jokes: the dried-out flesh and bones, the wooden boats in which the dead sail endlessly in no direction. What did you expect from gods with animal heads? Though come to think of it the ones made later, who were fully human were not such good news either. Favour me and give me riches, destroy my enemies. That seems to be the gist. Oh yes: And save me from death. In return we're given blood and bread, flowers and prayer, and lip service. 23 Maybe there's something in all of this I missed. But if it's selfless love you're looking for, you've got the wrong goddess. I just sit where I'm put, composed of stone and wishful thinking: that the deity who kills for pleasure will also heal, that in the midst of your nightmare, the final one, a kind lion will come with bandages in her mouth and the soft body of a woman, and lick you clean of fever, and pick your soul up gently by the nape of the neck and caress you into darkness and paradise. 24 Siren Song This is the one song everyone would like to learn: the song that is irresistible: the song that forces men to leap overboard in squadrons even though they see beached skulls the song nobody knows because anyone who had heard it is dead, and the others can’t remember. Shall I tell you the secret and if I do, will you get me out of this bird suit? I don’t enjoy it here squatting on this island looking picturesque and mythical with these two feathery maniacs, I don’t enjoy singing this trio, fatal and valuable. I will tell the secret to you, to you, only to you. Come closer. This song is a cry for help: Help me! Only you, only you can, you are unique at last. Alas it is a boring song but it works every time. 25 Spelling My daughter plays on the floor with plastic letters, red, blue & hard yellow, learning how to spell, spelling, how to make spells. I wonder how many women denied themselves daughters, closed themselves in rooms, drew the curtains so they could mainline words. A child is not a poem, a poem is not a child. there is no either/or. However. I return to the story of the woman caught in the war & in labour, her thighs tied together by the enemy so she could not give birth. Ancestress: the burning witch, her mouth covered by leather to strangle words. A word after a word after a word is power. At the point where language falls away from the hot bones, at the point where the rock breaks open and darkness flows out of it like blood, at the melting point of granite when the bones know 26 they are hollow & the word splits & doubles & speaks the truth & the body itself becomes a mouth. This is a metaphor. How do you learn to spell? Blood, sky & the sun, your own name first, your first naming, your first name, your first word. 27 The City Planners* Cruising these residential Sunday streets in dry August sunlight: what offends us is the sanities: the houses in pedantic rows, the planted sanitary trees, assert levelness of surface like a rebuke to the dent in our car door. No shouting here, or shatter of glass; nothing more abrupt than the rational whine of a power mower cutting a straight swath in the discouraged grass. But though the driveways neatly sidestep hysteria by being even, the roofs all display the same slant of avoidance to the hot sky, certain things: the smell of spilled oil a faint sickness lingering in the garages, a splash of paint on brick surprising as a bruise, a plastic hose poised in a vicious coil; even the too-fixed stare of the wide windows give momentary access to the landscape behind or under the future cracks in the plaster when the houses, capsized, will slide obliquely into the clay seas, gradual as glaciers that right now nobody notices. That is where the City Planners with the insane faces of political conspirators 28 are scattered over unsurveyed territories, concealed from each other, each in his own private blizzard; guessing directions, they sketch transitory lines rigid as wooden borders on a wall in the white vanishing air tracing the panic of suburb order in a bland madness of snows 29 The Landlady This is the lair of the landlady She is a raw voice loose in the rooms beneath me. the continuous henyard squabble going on below thought in this house like the bicker of blood through the head. She is everywhere, intrusive as the smells that bulge in under my doorsill; she presides over my meagre eating, generates the light for eyestrain. From her I rent my time: she slams my days like doors. Nothing is mine. and when I dream images of daring escapes through the snow I find myself walking always over a vast face which is the landlady's, and wake up shouting. She is a bulk, a knot swollen in a space. Though I have tried to find some way around her, my senses are cluttered by perception and can't see through her. She stands there, a raucous fact blocking my way: immutable, a slab of what is real. solid as bacon. 30 The Moment* The moment when, after many years of hard work and a long voyage you stand in the centre of your room, house, half-acre, square mile, island, country, knowing at last how you got there, and say, I own this, is the same moment when the trees unloose their soft arms from around you, the birds take back their language, the cliffs fissure and collapse, the air moves back from you like a wave and you can't breathe. No, they whisper. You own nothing. You were a visitor, time after time climbing the hill, planting the flag, proclaiming. We never belonged to you. You never found us. It was always the other way round. 31 The Rest The rest of us watch from beyond the fence as the woman moves with her jagged stride into her pain as if into a slow race. We see her body in motion but hear no sounds, or we hear sounds but no language; or we know it is not a language we know yet. We can see her clearly but for her it is running in black smoke. The cluster of cells in her swelling like porridge boiling, and bursting, like grapes, we think. Or we think of explosions in mud; but we know nothing. All around us the trees and the grasses light up with forgiveness, so green and at this time of the year healthy. We would like to call something out to her. Some form of cheering. There is pain but no arrival at anything. 32 The Shadow Voice My shadow said to me: what is the matter Isn't the moon warm enough for you why do you need the blanket of another body Whose kiss is moss Around the picnic tables The bright pink hands held sandwiches crumbled by distance. Flies crawl over the sweet instant You know what is in these blankets The trees outside are bending with children shooting guns. Leave them alone. They are playing games of their own. I give water, I give clean crusts Aren't there enough words flowing in your veins to keep you going. 33 This is a Photograph of Me It was taken some time ago At first it seems to be a smeared print: blurred lines and grey flecks blended with the paper; then, as you scan it, you can see something in the left-hand corner a thing that is like a branch: part of a tree (balsam or spruce) emerging and, to the right, halfway up what ought to be a gentle slope, a small frame house. In the background there is a lake, and beyond that, some low hills. (The photograph was taken the day after I drowned. I am in the lake, in the center of the picture, just under the surface. It is difficult to say where precisely, or to say how large or how small I am: the effect of water on light is a distortion. but if you look long enough eventually you will see me.) 34 Variation On The Word Sleep** I would like to watch you sleeping, which may not happen. I would like to watch you, sleeping. I would like to sleep with you, to enter your sleep as its smooth dark wave slides over my head and walk with you through that lucent wavering forest of bluegreen leaves with its watery sun & three moons towards the cave where you must descend, towards your worst fear I would like to give you the silver branch, the small white flower, the one word that will protect you from the grief at the center of your dream, from the grief at the center I would like to follow you up the long stairway again & become the boat that would row you back carefully, a flame in two cupped hands to where your body lies beside me, and as you enter it as easily as breathing in I would like to be the air that inhabits you for a moment only. I would like to be that unnoticed & that necessary. 35 Variations on the Word Love* This is a word we use to plug holes with. It's the right size for those warm blanks in speech, for those red heartshaped vacancies on the page that look nothing like real hearts. Add lace and you can sell it. We insert it also in the one empty space on the printed form that comes with no instructions. There are whole magazines with not much in them but the word love, you can rub it all over your body and you can cook with it too. How do we know it isn't what goes on at the cool debaucheries of slugs under damp pieces of cardboard? As for the weedseedlings nosing their tough snouts up among the lettuces, they shout it. Love! Love! sing the soldiers, raising their glittering knives in salute. Then there's the two of us. This word is far too short for us, it has only four letters, too sparse to fill those deep bare vacuums between the stars that press on us with their deafness. It's not love we don't wish to fall into, but that fear. this word is not enough but it will have to do. It's a single vowel in this metallic silence, a mouth that says O again and again in wonder and pain, a breath, a finger grip on a cliffside. You can hold on or let go. 36