Public Opinion and Polling

advertisement

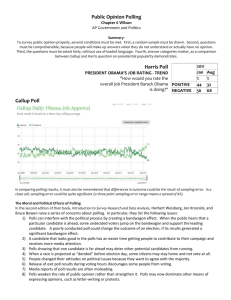

Public Opinion and Polling GV917 When was the First Poll? 1824 – The ‘Harrisburg Pennsylvanian newspaper ran a poll of its readers showing that Andrew Jackson was leading John Quincy Adams in the Presidential Campaign 1824 - The ‘Raleigh Star’ published a poll of 4,000 voters conducted at political meetings – Again, the poll put Jackson ahead of Adams They were both wrong – in 1824 Jackson won the contest (although his rival won in 1828) (see Nick Moon’s book ‘Opinion Polls, History, Theory and Practice) These were ‘Straw’ Polls A straw poll is an unsystematic survey with no clearly defined sample. eg A newspaper asks its readers to write in their opinions or viewers call in their votes on a TV talent contest Straw polls are fun – as long as they don’t attempt to generalise from the respondents to a wider population Representative Samples? The Columbus Despatch newspaper was the first to try to obtain a representative sample for a poll, using trained interviewers. They used ‘quota’ samples – asking interviewers to select quotas of age groups and sexes to make sure that they were representative of the city of Columbus. It became fashionable to select large samples since people thought they were more likely to be representative of the wider population In 1904 the New York Herald selected a sample of 30,000 for an opinion poll The ‘Literary Digest’ Approach The Literary Digest, a current affairs magazine, started polling in 1916 and had some initial success in predicting the outcome of Presidential Elections. They sought representative samples from telephone directories and car registration lists and sent their questionnaires through the post. By 1936 they mailed out 10 million questionnaires using this method and got about 2 million back. They had successfully predicted all the presidential elections up to that point since 1924 and they called the 1936 election for Alf Landon, the Republican candidate The arrival of the Gallup Polls George Gallup set up the American Institute of Public Opinion in 1935 and he had a different approach. He used much smaller but tightly controlled random samples interviewed by trained personnel. Gallup denounced the Literary Digest approach and the two organisations started trading insults in public. He predicted that Franklin Roosevelt would win the election and he was right. This was a disaster for the Literary Digest, which soon went out of business. Why did they go wrong using telephone directories and car registration data? Sampling Frame Opinion polls try to measure the public’s voting intentions at a given point of time with samples of 1,000 to 2,000 respondents. The UK electorate at the time of the 2010 election was more than 44,000,000 individuals A sampling frame is a list of the population that we are trying to survey eg The Electoral Roll, the Post Code Address file A sample will provide an accurate picture, as long as it is representative of the electorate. We can make sure of this by using a sampling frame to draw a random sample Random Samples Suppose we had copies of the electoral roll for the UK and we wanted a sample of about 1,500 individuals. If we selected every 30,000th name on the electoral roll at random we would get a sample of 44,000,000/30,000 = 1,467 individuals Notice that everyone on the electoral roll has a (small) chance of ending up in our sample. This makes it a random sample and so it should not differ much from the electorate as a whole in terms of its age, sex, occupational status, education, etc. The Literary Digest Poll was not a random sample – but was biased in favour of affluent people who owned a motor car or had a telephone at home – they tended to be Republicans Surveys in Britain Surveys have a long history in Britain. The first one was a census starting in 1086 conducted by King William. He had successfully invaded Britain from Normandy in 1066 and he wanted to know what assets his new land possessed. This produced the ‘Domesday’ book. (see http://www.middle-ages.org.uk/domesday-book.htm) But in the 19th century surveys in Britain took a different route from those in the United States. In 1935 the famous author H. G. Wells defined a social survey as: ‘A fact finding study dealing chiefly with working class poverty and with the nature and problems of the community’ Charles Booth, commenced the first really scientific study of poverty in London in 1886 – he used school attendance officers to report on levels of poverty experienced by the families of school children Poverty Surveys 1. 2. 3. Booth’s study was a landmark, but his definitions of poverty were vague. Eg he defined the category ‘very poor’ as ‘living in a state of chronic want’ Joseph Rowntree conducted a survey of poverty in York called ‘Poverty: A Study of Town Life’ published in 1902. He defined poverty much more precisely than Booth. He Interviewed families in York directly Used earnings as the measure of poverty Worked out a budget that a family would need to prevent them starving and then calculated how many people fell below this minimum income level Other studies of poverty followed: Bowley (1915); Ford (1928) Smith (1928). The most recent is a very sophisticated study conducted by Peter Townsend a former professor of Sociology and Essex, published in 1997. Opinion Polls in Britain George Gallup was so successful in the US that he branched out into Britain in 1936, creating the Institute for Public Opinion. See Antony King, Robert Wybrow and Alex Gallup, British Public Opinion 1937-2000 (Politicos) The Gallup organisation correctly predicted the loss of the election by Winston Churchill in 1945 – this was a big surprise to the media, which took no notice of opinion polls at the time. They thought that Churchill – the great war leader – would easily win Polling and SurveyAgencies in Britain British Market Research Bureau (TNSBMRB) IPSOS-MORI National Opinion Polls COMRES Opinion Research Services YouGov National Centre for Social Research How Accurate are the Polls? Political opinion polls are unique in that their accuracy can be checked by comparing the voting predictions from polls with the actual outcome of elections. Since election campaigns are dynamic and opinion shifts significantly over time, it is important to look at polls conducted late on the campaign – just before the vote takes place Changes in Voting Intentions during the General Election Campaign in Britain, 2005 (British Election Study) Changes in Leader Evaluations in the 2005 Campaign (British Election Study) What Happened in the Election? Party Vote Shares in 2005 Other 11% Liberal Democrats 22% Labour 35% Conservatives 32% How Did the Different Polling Agencies Do? Eve of Voting Predictions in the 2005 General Election Agency Labour Conservatives Liberal Democrats Other parties ComRes 39 31 23 6 ICM 38 32 22 8 IPSOS-MORI 38 33 23 6 NOP 36 33 23 9 Populus 38 32 21 9 YouGov 37 32 24 7 Harris 38 33 22 7 Actual Vote 35 32 22 10 Polling Agencies in 2005 On average the agencies were spot on with the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats But the overestimated the Labour vote and underestimated the ‘Others’ vote. Why? This could be due to methodological issues – failure to use random sample, interviewer effects, measurement problems etc But the most likely explanation is the nature of public opinion itself. What is Public Opinion? The ‘Filing Cabinet’ model The ‘Filing Cabinet’ model is the traditional view of the nature of public opinion. If you ask people about political leaders, or political events such as the Iraq war, or issues such as the state of the National Health Service – they will pull out of their memory a filing cabinet marked ‘David Cameron’, or the ‘Iraq war’, or the ‘NHS’ and describe its contents to you. This is misleading The public varies a lot in the extent to which it is interested in politics and knows about current events and political leaders. Generally it does not pay a great deal of attention to politics For individuals who are not very interested, when they are asked to express an opinion they will draw on very few actual facts These are often ‘Top of the head’ considerations – fragments of information they have picked up from the media or from the interviewer – of a limited scope (eg George Osborne looks miserable, or the government has been criticised for not doing well on the economy) In this interpretation public opinion does not exist in a predetermined state, but it is created dynamically during an interaction with the interviewer – opinions emerge ‘On the Hoof’ Levels of Interest in the General Election at the Start of the Campaign So what explains the bias in the polls? The most likely explanation is that just before the election was held people who were not very informed about politics had heard that Labour was leading in the polls – remember that all the reputable polls were putting Labour ahead They thought that the party was going to win the general election This influenced their responses to the question about how they were going to vote Perceptions of Who Will Win influences responses. Which Party Will Win the Election? 70 60 50 40 30 Percent 20 10 0 Labour Don’t know Liberal Democrats Conservatives Other Conclusions Public opinion is dynamic and varied Some people are well informed and give comprehensive answers to questions; Others are not very well informed and give very sketchy answers Some people really don’t have an opinion about some issues and so will say that they don’t know or alternatively answer randomly We have to know what polls can do and what they can’t do