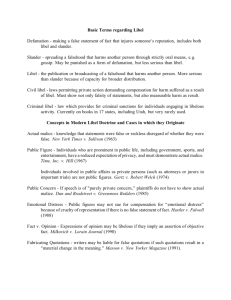

Libel and Slander / Defamation

advertisement

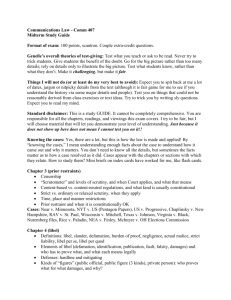

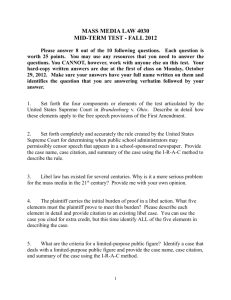

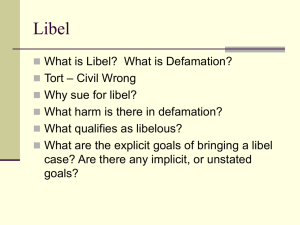

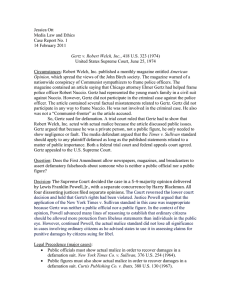

Communications Law. COMM 407, CSU Fullerton DEFAMATION CHAPTER 4: LIBEL AND SLANDER Protection of Person’s Reputation Basic human dignity: protection of one’s reputation from unjustified invasion and wrongful hurt Defamation of character Wrongfully hurting a person’s good reputation Slander (spoken) and Libel (written) Defamation is a civil wrong (tort) Any living person or legal entity (e.g., corporations) may sue for defamation. Special case: groups (members must be affected as individuals) Government organizations/agencies may not sue Tort: A civil wrong which can be redressed by awarding damages These wrongs result in an injury or harm constituting the basis for a claim by the injured party. Torts fall into three general categories: intentional torts, negligent torts, strict liability. There are numerous specific torts: trespass, assault, negligence, products liability, intentional infliction of emotional distress, nuisance, defamation, invasion of privacy. Libel suits are troublesome The most common legal problem faced by a person who work in the mass media: about 75% lawsuits filed against the media are in this category Lawsuits take a lot of money and time Damage claims are often outrageous Libel law is complicated and confusing (often judges make erroneous decisions) Some plaintiffs file frivolous libel lawsuits to silence the critics in the media Erroneous decisions For most judges a libel case is a new experience Jurors are confused by the legal concepts: e.g., actual malice Thus: 75% of libel cases are overturned by appeal courts The Lawsuit as a weapon “Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation” (SLAPP): Run that story and we will take you to court Although 90% of SLAPP lawsuits fail, they are intended to intimidate and silence a less powerful critic by so severely burdening them with the cost of a legal defense that they abandon their criticism. In 1992 California enacted a statute intended to prevent the misuse of litigation in SLAPP suits. It provides for a special motion at the outset of a lawsuit to strike a complaint where the complaint arises from conduct that falls within the rights of free speech and lacks any basis of genuine substance, evidence, or prospect of success. If this is demonstrated then the burden of proof shifts to the plaintiff, to present evidence demonstrating a reasonable probability of succeeding in their case by showing an actual wrong would exist as recognized by law, if the facts claimed were borne out. The filing of an anti-SLAPP motion stays all discovery. Elements of defamation Defamatory content Identification Publication Falsity Fault Harm / Compensation Defamatory content A communication which has the tendency to so harm the reputation of another as to lower him/her in the estimation of the community or to deter third persons from associating with him/her Defamatory content Imputations of criminal behavior Sexual references and implications Personal habits (honesty, integrity, etc) Ridicule (showing someone “uncommonly foolish or unnatural”) Business reputation Disparagement of property (product) Defamatory content Libel per se (in itself: damages are implied). A statement that is defamatory on its face (regardless of context): murderer, rapist, etc. Libel per quod: depending on the situation / context: communist, liberal, right-winger, etc. Today the distinction is not important: the plaintiff needs to prove damages in both… Fair Comment and Criticism: Fact versus Opinion (p. 145) Expressions of pure judgments are not subject to libel lawsuits But: Expressions of “opinion” may often imply an assertion of objective fact. Couching such statements in terms of opinion is often not sufficient. Distinguishing facts from opinions The precision and specificity of the statement The verifiability of the statement The literary context in which statement is made (e.g., satire) The “public context” of the statement Identification At least some of the readers or listeners must understand to whom the defamatory statement refers. Plaintiff explicitly named Suggesting plaintiff’s actual name Picture, drawing, description Similarities to fictional characters Publication Who made the statement? Who disseminated it? Who repeated it? It must be communicated to a ‘third person,’ someone other than the plaintiff or defendant Internet services are generally exempt from liability Fault: standard for truth/falsity The old strict liability standard (now unconstitutional) Strict liability on the part of the defendant: a defendant could be liable for defamation merely for publishing a false and defamatory statement The rules did not require that the defendant knew that the statement was false or defamatory in nature. The only requirement was that the defendant must have intentionally or negligently published the information. New York Times v Sullivan (1964) An ad in the N.Y. Times alleged that the arrest of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. in Alabama was part of a campaign to destroy King's efforts to integrate public facilities and encourage blacks to vote. L. B. Sullivan, the Montgomery city commissioner, filed a libel action against the newspaper claiming that the allegations against the police defamed him personally. Under Alabama law, Sullivan did not have to prove that he had been harmed; and a defense claiming that the ad was truthful was unavailable since the ad contained factual errors. Sullivan won a $500,000 judgment. New York Times v. Sullivan (1964) Question Did Alabama's libel law, by not requiring Sullivan to prove that an advertisement personally harmed him, unconstitutionally infringe on the First Amendment's freedom of speech and freedom of press protections? New York Times v. Sullivan (1964) Decision: 9-0 for New York Times The Court held that the First Amendment protects the publication of all statements, even false ones, about the conduct of public officials except when statements are made with actual malice: “that the statement was made with… knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.” New York Times v. Sullivan (1964) “The debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials” (from Justice Brennan’s opinion) Public persons and officials Public figures are those who thrust themselves “into the forefront of particular public controversies in order to influence the resolution of the issues involved” Public officials are those who have substantial government responsibility Gertz v. Welch (1974) (the new private person standard) Gertz was an attorney hired by a family to sue a police officer who had killed the family's son. In a magazine American Opinion, the John Birch Society accused Gertz of being a "Leninist" and a "Communistfronter" because he chose to represent clients who were suing a law enforcement officer. Gertz lost his libel suit because a lower court found that the magazine had not violated the actual malice test for libel which the Supreme Court had established in New York Times v. Sullivan (1964). Gertz v. Welch (1974) (the new private person standard) Question Does the First Amendment allow a newspaper or broadcaster to assert defamatory falsehoods about an individual who is neither a public official nor a public figure? Gertz v. Welch (1974) (the new private person standard) Decision: 5 to 4 for Gertz The Court reversed the lower court decision. The application of the New York Times v. Sullivan standard in this case was inappropriate because Gertz was neither a public official nor a public figure. Ordinary citizens should be allowed more protection from libelous statements than individuals in the public eye. However, the actual malice standard could be used in assessing claims for punitive damages by private persons. The Gertz Ruling (1974) (the new private person standard) As long as they do not impose liability without fault (strict liability), states are free to establish their own standards of liability for defamatory statements made about private individuals. Most states use negligence (lesser degree of fault) A few states use actual malice Negligence: failure to do something that he/she has a duty to do, and that a reasonable person would do. E.g., in journalism checking the facts Negligence Standard and Private Figures A plaintiff can establish negligence on the part of the defendant by showing that the defendant did not act with a reasonable level of care in publishing the statement at issue. basically: whether the defendant did everything reasonably necessary to determine whether the statement was true Some factors that the court might consider include: the amount of research undertaken prior to publication; the trustworthiness of sources; attempts to verify questionable statements or solicit opposing views; and whether the defendant followed other good journalistic practices. Classifying the Plaintiff: A Rough Guide Public Official: Government Employee + Substantial Control or Responsibility All-Purpose Public Figure: Career of Courting Media + Pervasive Fame and Influence Vortex Public Figure: Public Controversy + Voluntary Leadership Role Involuntary Public Figure: Pattern of Notorious Conduct + Prior (Undesired) Media Coverage Private Persons: Most Others Damages The sum of money the law imposes for a breach of some duty or violation of some right. Presumed (before Gertz’s case: the court assumed that any defamation would be harmful) Compensatory damages (special, actual) compensate the claimant for the quantifiable monetary losses suffered by the plaintiff Punitive damages are intended to reform or deter the defendant and others from engaging in conduct similar to that which formed the basis of the lawsuit Limits on damages Large awards inhibit the vigorous exercise of First Amendment Private plaintiffs must provide solid evidence of their injuries or prove actual malice Punitive damages only when actual malice is proven (even in private persons cases). Privilege (also in Chapter 8) Absolute privilege: members of Congress engaged in congressional debates Also: most government officials while conducting their official duties Qualified (conditional) privilege: a libel defense that allows the media to report on government proceedings and records without fear of libel suit Libel and emotional distress Hustler Magazine v. Falwell (1988) In a parody that appeared in Hustler magazine the prominent fundamentalist evangelist Reverend Jerry Falwell was depicted as a drunk in a sexual liaison with his mother in an outhouse From the “Campari Ad” But your mom? Isn’t it a bit odd? I don’t think so. Looks don’t mean that much to me in a woman. Go on. Well, we were drunk off our God fearing asses on Campari, ginger ale and soda… And mom looked better than a Baptist whore with a $100 donation. From the “Campari Ad” Did you try it again? Oh, yeah. I always get sloshed before I go out to the pulpit. You don’t think I could lay down all that bullshit sober, do you? Hustler Magazine v. Falwell (1988) Falwell sued for: 1. libel, 2. invasion of privacy, 3. intentional infliction of emotional distress. In the trial court he lost on (1) and (2) but prevailed on (3). He was awarded $200,000 damages for emotional distress Hustler Magazine v. Falwell (1988) The Supreme Court reversed (8 to 0): a public figure or official may not recover for intentional infliction of emotional distress arising from a publication unless the publication contains a false statement of fact that was made with actual malice. Hustler Magazine v. Falwell (1988) That the material might be deemed outrageous and that it might have been intended to cause severe emotional distress were not enough to overcome the First Amendment. Hustler Magazine v. Falwell (1988) Vicious attacks on public figures are part of the American tradition of satire and parody, a tradition of speech that would be hamstrung if public figures could sue them anytime the satirist caused distress.