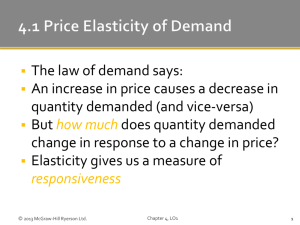

Elastic and Inelastic Demand (a)

Price elasticity of demand shows how responsive

consumers are to price changes.

elastic demand means % change in quantity demanded is

more than % change in price

inelastic demand means % change in quantity demanded

is less than % change in price

unit-elastic demand means % change in quantity demand

equals % change in price

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Elastic and Inelastic Demand (b)

Figure 3.1 Page 61

Inelastic Demand Curve

for Ice cream Cones

2.40

2.40

20%

2.00

D1

1.60

50%

1.20

0.80

0.40

0

500

1000

Quantity Demanded

(cones per winter month)

Price ($ per cone)

Price ($ per cone)

Elastic Demand Curve

for Ice Cream Cones

20%

2.00

D2

1.60

10%

1.20

0.80

0.40

0

500

1000

Quantity Demanded

(cones per summer month)

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

1800 2000

Perfectly Elastic and Perfectly

Inelastic Demand (a)

Perfectly elastic demand means a constant price and a

horizontal demand curve.

Perfectly inelastic demand means a constant quantity

demanded and a vertical demand curve.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Perfectly Elastic and Perfectly Inelastic Demand (b)

Figure 3.2 Page 62

Perfectly Inelastic

Demand Curve

for Insulin

D3

1.60

0

D4

Price ($ per tonnes)

Price ($ per tonnes)

Perfectly Elastic

Demand Curve

for Soybeans

0

Quantity Demanded

(tonnes)

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

1000

Quantity Demanded

(litres)

Total Revenue and the Price

Elasticity of Demand (a)

A price change causes total revenue to change in the

opposite direction when demand is elastic.

A price change causes total revenue to change in the

same direction when demand is inelastic.

A price change does not affect total revenue when

demand is unit-elastic.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Revenue Changes with Elastic Demand

Figure 3.3 Page 63

Price ($ to rent a DVD)

Demand Curve for DVDs

5

4

A

3

2

D

B

C

1

0

500

1000

1500

Quantity Demanded (DVDs rented each day)

As price increases – total revenue decreases

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Revenue Changes with Inelastic Demand

Figure 3.4 Page 64

Price ($ per ride)

Demand Curve for Amusement Park Rides

5

4

3

E

2

F

1

0

2000

4000

D

G

6000

8000

10 000

Quantity Demanded (riders each day)

As price increases – total revenue increases

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Total Revenue and the Price Elasticity of Demand (b)

Figure 3.5 Page 64

Demand Elasticity and Changes in Total Revenue

Price

Change

Change in

Total Revenue

up

down

down

up

Inelastic Demand

up

down

up

down

Unit-Elastic Demand

up

down

unchanged

unchanged

Elastic Demand

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Determinants of the Price

Elasticity of Demand

There are four determinants:

portion of consumer incomes (products with smaller

portions more inelastic)

access to substitutes (products with more substitutes

more elastic)

necessities versus luxuries (more inelastic for necessities

and more elastic for luxuries)

time (more elastic with the passage of time)

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Calculating Price Elasticity of

Demand

A numerical value for price elasticity of demand (ed) is

found by taking the ratio of the changes in quantity

demanded and in price, each divided by its average

value.

In mathematical terms:

ed =

ΔQd ÷ average Qd

Δprice ÷ average price

The sign will be negative (-) proving the law of

demand. Inverse relationship between Quantity

demanded and Price

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Elasticity and a Linear Demand

Curve (a)

A linear demand curve has a different price elasticity

(ed) at every point.

At high prices, the change in quantity demanded ( is

relatively large relative to average quantity demanded

,giving a large ed.

Elastic

At low prices, the change in quantity demanded is

relatively small relative to average quantity demanded,

giving a small ed.

Inelastic

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Income Elasticity

Income elasticity (ei) is the responsiveness of a

product’s quantity demanded to changes in consumer

income.

In mathematical terms:

ei = ΔQd ÷ average Qd

ΔI ÷ average I

Positive sign (+)shows a direct relationship, thus the

product is a normal product.

Negative sign (-) shows an inverse relationship, thus

the product is an inferior product.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Cross-Price Elasticity

Cross-price elasticity (ei) is the responsiveness of the

quantity demanded of one product (x) to a change in

price of another (y). In mathematical terms:

exy = ΔQdx ÷ average Qdx

ΔPy ÷ average Py

Positive sign indicates substitute product. (direct

relationship) Negative sign indicates complementary

product (inverse relationship)

ex. price CD players goes up demand of CDs goes

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

down

Limited. All rights reserved.

Elastic and Inelastic Supply

Price elasticity of supply measures the responsiveness

of quantity supplied to price changes.

Elastic supply means % change in quantity supplied is

more than % change in price.

Inelastic supply means % change in quantity supplied is

less than % change in price.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Elastic and Inelastic Supply

Figure 3.7, Page 70

Inelastic Supply Curve

For Tomatoes

4

S1

3

50%

2

100%

1

0

100 000

Price ($ per kilogram)

Price ($ per kilogram)

Elastic Supply Curve

for Tomatoes

200000

Quantity Supplied

(kilograms per year)

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

4

S2

3

50%

2

1

0

20%

100 000 120 000

Quantity Supplied

(kilograms per year)

Perfectly Elastic and Perfectly

Inelastic Supply

Perfectly elastic supply means a constant price and a

horizontal supply curve.

Perfectly inelastic supply means a constant quantity

supplied and a vertical supply curve.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Time and the Price Elasticity of

Supply (a)

Price elasticity of supply changes over three

production periods:

Supply is perfectly inelastic in the immediate run.

Supply is either elastic or inelastic in the short run.

Supply is perfectly elastic for a constant-cost industry

and very elastic for an increasing-cost industry in the

long run.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Time and the Price Elasticity of Supply (b)

Figure 3.8, Page 71 (continued in part (e))

Price ($ per kilogram)

S1

0

750 000

Short-Run

Supply Elasticity

For Strawberries

Price ($ per kilograms)

Immediate-Run

Supply Elasticity

for Strawberries

S2

2.50

2.00

0

Quantity Supplied

(kilograms per month)

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

9

11

Quantity Supplied

(millions of kilograms per year)

Time and the Price Elasticity of

Supply (c)

If strawberries are produced in a constant-cost

industry:

A higher price of strawberries raises production but not

resource prices.

As new businesses enter the industry in the long run

due to a higher price of strawberries, this price is

gradually pushed back down to its original level.

Therefore the long-run supply curve for a constant-cost

industry is perfectly elastic.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Time and the Price Elasticity of

Supply (d)

If strawberries are produced in a increasing-cost

industry:

A higher price of strawberries raises production and also

resource prices.

As new businesses enter the industry in the long run

due to a higher price of strawberries, this price is

gradually pushed back down to its lowest possible level,

but this level is higher than it was originally.

Therefore the long-run supply curve for an increasingcost industry is very elastic.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Time and the Price Elasticity of Supply (e)

Figure 3.8, Page 71 (continued from part (b))

Price ($ per kilograms)

Long-Run Supply Elasticity

S4

S3

2.00

Increasingcost Industry

0

Quantity Supplied

(millions of kilograms per decade)

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Constantcost Industry

Calculating Price Elasticity of

Supply

A numerical value for price elasticity of supply (es) is

found by taking the ratio of the changes in quantity

supplied and in price, each divided by its average

value.

In mathematical terms:

es =

ΔQs ÷ average Qs

Δprice ÷ average price

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Excise Taxes (a)

An excise tax is a tax on a particular product expressed

as a dollar amount per unit of quantity.

Such a tax creates a new supply curve (S1) seen by

consumers. It is vertically above the initial supply

curve (S0) seen by producers.

The reason for this difference is that the price as seen by

consumers is now higher than that seen by producers.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Excise Taxes (b)

The after-tax price for consumers is found where S1

crosses the demand curve. The after-tax equilibrium

price for producers is the corresponding price on S0.

The total tax paid by consumers is found by multiplying

their tax-induced price rise by after-tax quantity.

Similarly, the total tax paid by producers is found by

multiplying their corresponding price drop by after-tax

quantity.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

The Impact of an Excise Tax

Figure 3.9, page 74

The Impact of an Excise Tax

Market Demand and Supply

Curves For Strawberries

4.00

Price

3.00

S1

3.50

Quantity

Quantity

Demanded

Supplied

($ per

(D)

(S0) (S1)

tonne)

(millions of tonnes)

3.00

2.50

2.00

1.50

1.00

5

7

9

11

13

13

11

9

7

5

9

7

5

3

1

Price ($ per kg)

b

a

2.50

S0

$1

A

2.00

B

c

d

1.50

1.00

D

0.50

0

1

3

5

7

9

11

13

Quantity (millions of kg per year)

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

15

The Effect of Elasticity

For a given supply curve, the more elastic the demand

curve the greater the proportion of an excise tax paid

by producers. Quantity demanded will decrease by a

greater percentage than the price increase.

For a given demand curve, the more elastic the supply

curve the greater the proportion of an excise tax paid

by consumers. Quantity supplied will decrease by a

greater percentage than price increase.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Excise Taxes and Demand Elasticity

Figure 3.10, page 75

Elastic Demand

Inelastic Demand

S1

S1

S0

b

b

S0

2.25

2.00

c

A

D

B

1.25

a

2.75

$1

d

Price ($ per kg)

Price ($ per kg)

a

$1

A

c

2.00

B

1.75

d

D

6

9

Quantity (millions of kg per year)

8

9

Quantity (millions of kg per year)

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Excise Taxes and Supply Elasticity

Figure 3.11, page 76

Elastic Supply

Inelastic Supply

S1

S0

b

S1

b

2.75

$1

A

2.00

1.75

$1

B

S0

c

d

D

6

Price ($ per kg)

Price ($ per kg)

a

a

2.25

2.00

A

B

1.25

d

9

Quantity (millions of kg per year)

c

8

D

9

Quantity (millions of kg per year)

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Price Controls

A price floor is a minimum price set above the

equilibrium price.

It results in a surplus in the market.

A price ceiling is a maximum price set below the

equilibrium price.

It results in a shortage in the market.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Agricultural Price Supports

Price supports for agricultural goods are an example of

a price floor.

They help overcome unstable agricultural prices.

Farmers win from these supports.

Consumers and taxpayers lose from these supports.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Reasons for Price Supports

Figure 3.12, page 78

Market Demand and Supply

Curves for Wheat

Market Demand and Supply

Schedules for Wheat

140

Price

120

S1

S0

Quantity

Quantity

Demanded

Supplied

($ per

(D)

(S0)

(S1)

tonne)

(millions of tonnes)

$140

120

100

80

60

10

11

12

13

14

14

13

12

11

10

12

11

10

9

8

Price ($ per tonne)

b

100

a

80

60

D

40

20

0

1

2 3 4

5

6

7

8

9 10 11 12 13 14

Quantity (millions of tonnes per year)

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Effects of Price Supports

Figure 3.14, page 79

Market Demand and Supply Curves

for Milk

Market Demand and Supply

Schedules for Milk

$1.30

Quantity Quantity

Demanded Supplied

(D)

(S)

(millions of litres)

59

62

1.10

60

60

0.90

61

58

S

Price ($ per litre)

Price

($ per

litre)

surplus

1.30

1.10

.90

A price floor

creates

a surplus.

.70

0

58

60

D

61

59

Quantity

(millions of litres per year)

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

62

Rent Controls

Rent controls are an example of a price ceiling.

They keep down prices of controlled rental

accommodation.

Some (especially middle-class) tenants win from these

controls.

Other (especially poorer) tenants lose from these

controls.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Effects of Rent Controls

Figure 3.15, page 80

Market Demand and Supply

Curves for Units

Market Demand and Supply

Schedules for Units

Price

($ rent

per

month)

Quantity

Quantity

Demanded

Supplied

(D)

(S)

(units rented per month)

$700

1700

2500

500

2000

2000

300

2300

1500

Price ($ per unit)

S

700

A price ceiling

creates

a shortage.

500

300

shortage

0

1500

2000 2300 2500

Quantity

(units rented per month)

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

D

Prophet of Capitalism’s Doom

According to Karl Marx’s theory of exploitation:

a product’s price is based on the amount of labour that

goes into producing it

capitalists cut costs by minimizing workers’ wages and

by maximizing the length of the workday

capitalists keep any surplus value, which is the excess of

their revenues over their costs

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Marx’s Theory of Exploitation

Figure A, Page 87

Creation of Surplus Value

Creation of Surplus Value

$50 Wage

$30 Wage

Daily Wage

$50

$30

Materials and

machine wear

and tear (M)

$10

$10

Surplus Value (SV)

$20

$40

Total Value

$80

$80

Exploitation Rate

2

4

(SV/W)

5

3

Value produced ($ per day)

(when producing 2 shirts or 1 suit)

80

60

W = 30

W = 50

W = 10

40

20

0

M = 10

SV = 10

SV = 40

$50

$30

Daily Wage

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

For the Public Good (OLC)

Besides intervening in private markets, Canadian

governments have an independent role.

Government programs include payments to adults

with children, retirement funds for the elderly,

unemployment insurance, welfare, higher education

subsidies, free health care and schooling, and

subsidized public housing.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

For the Public Good (OLC)

Federal Spending

The main federal spending programs are:

transfer payments to seniors (the Seniors Benefit)

tax credits to low-income parents (the Child Tax Credit)

transfer payments to the unemployed (Employment

Insurance)

pensions (the Quebec and Canada Pension Plans)

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

For the Public Good (OLC)

Provincial and Territorial Spending

The responsibilities of provincial and territorial

governments include:

health care

subsidies for post-secondary education

welfare services

The federal government pays a portion of these costs

through the Canada Health and Social Transfer

(CHST).

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

For the Public Good (OLC)

Government Expenditures

Figure A

Federal (2009)

($ billions)

Goods and services

Transfers to

Persons

Businesses

Nonresidents

Provinces and local

Debt charges

Provincial (2009)

($ billions)

63.9

87.9

4.5

4.8

65.1

26.1

Goods and services

Transfers to

Persons

Businesses

Governments

Debt charges

253.1

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

214.1

Local (2009)

($ billions)

43.1

11.1

52.5

28.3

Goods and services 109.1

Transfers to

Persons

4.0

Businesses

2.2

Provinces

0.1

Debt Charges

3.5

349.2

118.9

For the Public Good (OLC)

Taxation (a)

Canadian governments use five main types of taxation:

Personal income taxes are levied by both federal and

provincial governments, and are based on four marginal

federal tax rates (15%, 22%, 26%, and 29%).

Sales taxes are levied by both federal and provincial

governments, and are charged as a percentage of price

on a wide range of products.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

For the Public Good (OLC)

Taxation (b)

Excise taxes are levied by both federal and provincial

governments, and are usually charged as a dollar amount

per unit of quantity on particular products.

Property taxes are charged by local governments on

buildings and land.

Corporate income taxes are paid by corporations to both

federal and provincial governments as a percentage of

annual profits.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

For the Public Good (OLC)

Tax Revenues for All Levels of Government (2009)

Figure B

Personal income taxes

Sales and excise taxes

Property taxes

Corporate income taxes

Miscellaneous taxes

Percent of

Gross Domestic Product

Percent of

Total Taxes

11.5

8.7

3.2

2.5

4.6

37.6

28.4

10.5

8.2

15.0

30.5

100.0

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

For the Public Good (OLC)

Taxes and the Canadian Economy

Figure C

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

For the Public Good (OLC)

Debates over Government’s Role (a)

Taxes have increased significantly as a proportion of

the total Canadian economy over the past few decades.

Critics argue that taxes and some spending programs

reduce productive activity.

Critics also contend that many government programs

are inequitable, and hampered by administrative

problems.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

For the Public Good (OLC)

Debates Over Government’s Role (b)

Supporters of government admit that public spending

and taxation are not as effective as they could be. But

they argue that these problems need to be seen in

perspective, given that private markets are also subject

to a variety of flaws.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Chapter 3

The End

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.