Spring 2013 issue - Amazon Web Services

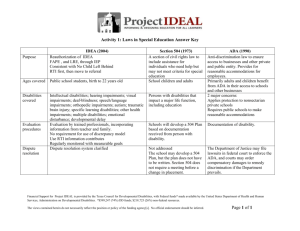

advertisement