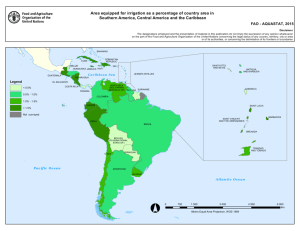

Chapter 16 Plant nutrition, transport and adaptation to stress

advertisement

Chapter 17: Plant nutrition, transport and adaptation to stress Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-1 Nutrition of plants • The nutritional requirements of plants are relatively simple • Light, carbon dioxide and water for photosynthesis and certain mineral elements that are also required for growth • In multicellular plants, light and carbon dioxide are obtained above ground, while water and mineral nutrients are generally taken up from the soil Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-2 Nutrition of plants (cont.) • Plant nutrients may be required in large (macronutrient) or small (micronutrient) quantities • Fourteen mineral elements are essential for plant growth Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-3 Table 17.1: Essential mineral elements Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-4 Nutrition of plants (cont.) • Plants growing on soils that are deficient in a certain essential element may have stunted growth or be more susceptible to disease • For example, plants growing on iron-deficient soils typically become yellow (chlorotic) Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-5 Fig. 17.2: Seedlings grown on alkaline calcareous soil Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-6 Nutrition of plants (cont.) • Mineral nutrients in the form of ions serve general functions in plants by moderating the ionic balance of cells and regulating water balance • Minerals may also have specific functions, e.g. – Mg2+ is a component of chlorophyll – K+ affects the conformation of certain proteins – Ca2+ is vital in maintaining the physical properties of membranes and as a component of primary cell walls • Many trace elements form part of enzymes that are essential in metabolic processes Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-7 Nutrition of plants (cont.) • Plants obtain essential nutrients from the soil, which is formed from the weathering of underlying rocks • However, such nutrients may also be obtained from the decomposition of dead plant and animal matter by the action of bacteria and fungi • Nutrients move in cycles among pools of available sources: the amount of a specific nutrient depends more on its amounts in various pools and the rates of movement among them than on the very slow release of the nutrient from the underlying rocks Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-8 Nutrition of plants (cont.) • Nitrogen is absent from lithospheric rocks but abundant in the atmosphere • Nitrogen (N2) is ‘fixed’ by certain bacteria to form ammonium (NH4+) and eventually nitrate (NO3–), which are then absorbed by plant roots • Such bacteria may live freely in the soil or in association with plants, such as Rhizobium bacteria in root nodules of legumes, or actinomycetes in the roots of casuarinas (she-oaks) Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-9 Question 1: How are many Australian native plants able to survive on low-nutrient soils? A mechanism commonly found is: a) A shorter life-cycle, leading to avoidance of the stress b) The development of fine roots, which increases root surface area and phosphorus uptake c) Increased shoot growth and a reduction in root growth d) Specialised structures in the leaves that are able to trap airborne phosphorus particles Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-10 Pathways and mechanisms of transport • Unicellular organisms do not require systems to transport nutrients and water—the small distances across which materials move means that simple diffusion is adequate • In contrast, tall vascular plants require transport systems to distribute nutrients and water Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-11 Transport pathways • Transport pathways in plants include those – between the soil and plant root – between cells either along the apoplastic or symplastic pathways – between compartments within a cell – involved in long-distance transport, i.e. the xylem and phloem Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-12 Fig. 17.4: Vacuolated plant cells Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-13 Transport mechanisms • Include both passive and active processes • Passive processes include diffusion, mass flow and osmosis • Mass flow transport occurs in xylem and phloem, and involves the carrying of solutes in solution, driven by gradients of hydrostatic pressure • Active processes, which require the expenditure of energy, involve the uptake or movement of ions or sugars Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-14 Water transport • The movement of water molecules from the soil into roots or from leaf mesophyll cells through stomata into the atmosphere occurs down gradients of water potential (Ψ, psi) Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-15 Fig. 17.5: Gradients of free energy of water Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-16 Factors that affect water potential • In soil and within a plant, Ψ is less than zero, and thus is negative. This is because the free energy of water molecules decreases, due to the presence of solutes and solids that absorb water molecules, to below that of pure water – e.g. a 1.0 M sucrose solution has a water potential (Ψsolution) of –3.5 MPa Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-17 Fig. 17.6: Net flow of water Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-18 Factors that affect water potential (cont.) • Water potential is affected by hydrostatic pressure, which is decreased when a fluid is under tension (negative Ψ), as in the xylem, and increased by application of positive pressure, such as occurs in a turgid plant cell Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-19 Fig. 17.7: Water potential of a plant cell Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-20 Factors that affect water potential (cont.) • The elastic properties of a plant cell wall mean that it can swell and contract as the water content and volume of the cell alter • The cell wall is thus able to exert a positive hydrostatic or turgor pressure on the cell contents • Thus, the water potential of a plant cell (Ψcell) is the sum of the turgor pressure (pressure potential, ΨP) and the negative osmotic effect (osmotic potential, Ψ) of solutes Ψcell = ΨP + Ψ Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-21 Water uptake by plant cells • When plant cells exchange water with their environment, they shrink or swell to a limit imposed by the cell wall • Both the pressure (ΨP) and osmotic (Ψ) potentials change in response to changes in cell water content • If cell water content and volume increase, cell walls distend and ΨP increases, the solutes are diluted, and both Ψ and Ψcell become less negative • When a cell is fully turgid, ΨP = Ψ and Ψcell = 0 Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-22 Fig. 17.9: Leaves of a cucumber plant Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-23 Water uptake by plant cells (cont.) • On a hot day, water vapour that diffuses through stomata often exceeds that taken up by roots • If this occurs, cells lose water, their volume decreases, ΨP decreases and both Ψ and Ψcell become more negative • The capacity of the cell to absorb water from surrounding cells is greatly increased and water moves into the cell • During drought conditions, plants use changes in turgor to adjust their water-retaining and waterabsorbing capacities Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-24 Osmotic adjustment in plant cells • Plants inhabiting areas that have persistent soil water deficits over days or weeks (i.e. drought stress) may respond by increasing the amount of solute in cell vacuoles • This has the effect of decreasing Ψ and Ψcell without adversely affecting cell turgor and growth • This response to drought is osmotic adjustment, and it allows photosynthesis and continued growth in drier conditions Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-25 Transpiration • Transpiration is the loss of water by evaporation from leaves using energy from incoming solar radiation to vaporise water Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-26 Fig. 17.11: Movement of CO2 and water vapour into and out of a leaf Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-27 Transpiration (cont.) • In a well-watered plant, transpired water is replaced by water drawn up from the roots through the xylem • On sunny days, plants may lose large amounts of water – e.g. the amount of water transpired by a mountain ash tree, Eucalyptus regnans, growing in a moist habitat, may be as much as 300 litres/day • Along an increasingly negative gradient of water potential, water enters the roots and moves through the apoplast by mass flow, but at the endodermis it must travel via the symplast to enter the root stele Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-28 Water movement in xylem • In flowering plants, xylem includes vessels and tracheids • Vessels consist of elements joined end-to-end to form a tube that may extend up to 15 m in length • Xylem sap, which forms a continuous column from the root to the leaf veins, comprises a dilute solution of inorganic ions and nitrogenous compounds • The continuous column of sap is under tension, due to the narrow diameter of xylem and the cohesive nature of water cohesion theory Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-29 Fig. 17.13: Xylem sap is tapped from roots of mallee gums by Aboriginal Australians at Yalata Reserve, SA Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-30 Water movement in xylem (cont.) • When the tension in xylem sap becomes too high, the water column may break or cavitate • Under conditions of high humidity and soil moisture, root pressure may drive the flow of xylem sap Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-31 Fig. 17.14: Cavitation in a xylem vessel Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-32 Water movement from leaves • The loss of water vapour from leaves is dependent on two factors (i) the cuticle, which is highly resistant to water loss, and stomata, through which moves 90 per cent of water vapour flux (ii) the leaf boundary layer—that layer of still air just outside the leaf surface Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-33 Fig. 17.15: Transpiration Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-34 Water movement from leaves (cont.) • Stomatal pores occupy only a small proportion of the leaf surface area • By controlling the number of stomata and the size of stomatal pores, a plant can regulate the exchange of CO2, O2 and water vapour • The size of stomatal pores is dependent on the turgor of guard cells • Guard cells are turgor-regulated valves that expand outward to open the pore when turgid, but which deflate and close under conditions of turgor loss Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-35 Control of stomatal opening and closing • Stomatal opening and closing is the result of movement of solutes, particularly K+ and Cl–, into and out of guard cells • Stomata open and close in response to a number of stimuli, including light intensity, CO2 concentration, air humidity, and soil and leaf water deficits • During drought, plant roots generate the hormone abscisic acid, which induces stomatal closure Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-36 Question 2: What effect do you think a hot, dry wind would have on transpiration rate and stomatal opening? a) Slow down and open up b) Slow down and close c) Speed up and open up d) Speed up and close Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-37 Translocation of assimilates • The end products (or assimilates) of photosynthesis are translocated from the leaves (the source) to other parts (the sinks) of the plant • Assimilates move via the phloem to actively growing parts of a plant, such as the roots, the youngest expanding leaves and the shoot tip • Phloem sap is a concentrated solution of solutes, predominantly sucrose • The rate of phloem transport ranges from 40 to 100 cm per hour Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-38 Fig. 17.21: Ring-barking Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-39 Fig 17.23: Phloem-feeding aphids Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-40 Adaptations to stress • During uptake of CO2 for photosynthesis, plants lose water through stomata • When water loss is greater than that which may be taken up from the soil, plants may undergo water stress, which may impair growth and normal plant functioning • Annual plants escape drought by germinating, growing, flowering and setting seed only during periods when water is available • In arid habitats, perennial plants must be drought tolerant, and achieve this by either avoiding or tolerating dehydration Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-41 Ways that plants cope with drought • Plants avoid dehydration by either increasing water absorption, reducing transpirational loss, or both • Deep, extensive root systems are able to extract water from a large soil volume • High root:shoot ratios are common among arid zone taxa, and others may shed leaves to reduce the leaf area across which water may be lost Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-42 Ways that plants cope with drought (cont.) • Succulent species such as cacti are able to store water in specialised cells • Leaf hairiness or waxiness is often higher for arid zone taxa, as these increase reflectance of solar radiation, thereby reducing leaf temperature and the need for evaporative cooling Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-43 Salinity and mineral stress • High soil salt concentrations can cause water stress and sodium (Na+) toxicity to plants • Plant adaptations to salinity include – separation and storage of ions within specialised cells – ability to exclude salt at roots or excrete it from the leaves – maintenance of a balance between ion uptake and transpiration and growth • Ion toxicity can result from an increase in concentration of ions at low soil pH or from the effects of pollutants that facilitate entry of toxic ions Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-44 Lack of oxygen around roots • Lack of oxygen in waterlogged soil decreases cellular respiration by root cells, which impairs root growth and water and nutrient uptake • Plants such as mangroves possess adaptations to low soil oxygen – These include anatomical features such as air canals in roots or the production of lateral roots on the soil surface • Biochemical adaptations to low soil oxygen include an increased ability to sustain aerobic fermentation in roots and an increased resistance to toxic compounds produced in anaerobic soils Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-45 Temperature stress • Different parts of a plant may be subject to quite different temperature regimes • Temperature affects biochemical reactions due to its effects on the kinetic energy of reactants and the tertiary structure of enzymes and membranes • In cold environments, plants are able to survive very low temperatures by preventing intracellular ice formation Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-46 Summary • Plants require light, carbon dioxide, water and inorganic nutrients for growth • Xylem and phloem are the transport pathways between different parts of a plant • Water movement in a plant is down gradients of water potential • Translocation of assimilates in phloem requires energy • Individual plants can respond to environmental stress within limits defined by their genotype Copyright 2010 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PowerPoint slides to accompany Biology: An Australian focus 4e by Knox, Ladiges, Evans and Saint Slides prepared by Karen Burke da Silva, Flinders University 17-47